‘Non-Violence’, a sculpture by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, in front of UN headquarters in New York City © Wikicommons

The record of the United Nations in fulfilling its founding goals is variable, to put it kindly. Yes, it has some successes to its name, but it has also been accused of being irresolute, indecisive, overcautious and vacillating. The goals of those who set it up in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War were fourfold: to keep peace in the world; to encourage and develop friendly relations between nations; to cooperate, so as to help people live better lives by eliminating poverty, disease and illiteracy, while striving to stop environmental destruction. It was also supposed to encourage respect for one another’s rights and freedoms. That third one looks to me like five aims rolled into one. And finally, to be a centre for helping nations achieve these aims, which I think hardly counts as a separate goal at all. All very laudable, of course, and sometimes it has worked; but only sometimes. Look at the letters that represent it: “U” and “N”, for United Nations: the 21st and 14th letters of the alphabet in that order, as expressed in English, and representing the most ambitious multinational project the world has ever seen. Interestingly, if we’re going 7 letters at a time , the next one should be “G”, which would produce the word “gun”, not a very propitious outcome, I fear, however predictive. I hesitate to say: “most successful” with regard to the UN, but “most ambitious”, certainly. They are also the letters used to turn a word into its own negative: “Natural – Unnatural”, for instance; “Happy – Unhappy”; or “Known – Unknown”, or how about “Expected – Unexpected”? But they are also the first letters of the word “unity”, which the UN was set up to achieve but has not really succeeded in doing, if not for want of trying; unity still evades the world and probably always will.

Of course, “un” is French for “one”, at least in its masculine form, derived from the Latin unus, una or unum. The Romans had a neuter gender as well as masculine and feminine, of course. As you know, for the feminine version in French, add an “e” to the end, as in the title of that haunting song that won the 1971 Eurovision Song Contest for Monaco: “Un Banc, Un Arbre, Une Rue” (a bench, a tree, a street), performed by the lovely French singer, Séverine, and composed by Jean-Pierre Bourtayre, with words by Yves Dessca.

However, among the UN’s 193-strong membership there’s very little sign of unity. Because each member has equal power, and in the Security Council (but not in the General Assembly) one individual country has the right to block a resolution, as Russia’s representative has done with any motion seen as critical of Russia’s vicious military incursion into Ukraine, the UN’s effectiveness has been called into question. President Vladimir Putin calls his bloody invasion a “special military operation”, of course, and definitely not a war, whilst denying his troops have been targeting civilians and private homes and also denying the great many rapes and beatings they’re alleged to have carried out. But, there again, he told his soldiers they’d be welcomed as “liberators” by the Ukrainian people (which I imagine he must have known to be untrue) and that his aim was to “de-naziy” the country, although before he turned up nazis were in fairly short supply there.

Russia justifies its vicious aggression by saying it is trying to protect pro-Russian separatists in the Donbass region from ‘unwarranted’ attacks by Ukraine’s armed forces, and when a minute’s silence was declared at a meeting of the UN security Council to remember Ukraine’s many dead, the Russian envoy, Vassily Nebenzia, insisted that the silence must also be for the rebels who had died, killed – he claimed – by Ukrainians that Russia has described as ‘ultra-nationalists’. Nebenzia failed to mention the 298 innocent passengers of Malaysian airlines flight MH17, brought down by a Russian-made SA-11 missile, presumably fired by the separatists (it remains unproven, although it was launched from the area held by rebels, who also had access to this type of missile) in the mistaken belief that it was a military flight.

Norway’s ambassador, Mona Juul, believes that Nebenzia should not have been allowed to participate in the vote. “A veto cast by the aggressor undermines the purpose of the council,” Juul said. “It’s a violation of the very foundation of the U.N. Charter. Furthermore, in the spirit of the charter, Russia, as a party, should have abstained from voting on this resolution.” Nebenzia would not have dared to abstain, I suspect.

In early May, the Security Council finally agreed on a resolution calling for peace in Ukraine, that was actually supported by Russia, although Russia denies it’s engaged in war, of course; merely an operation to “denazify” the country. Killing everyone who lives there would seem to be a rather extreme way to achieve that end, even supposing that the country is chock full of Nazis, which it clearly is not. Why this proposal involves bombing and shelling houses, apartment blocks, a theatre, factories, and schools is not clear. Even so, the adoption of the resolution was welcomed.

“Today, for the first time, the Security Council spoke with one voice for peace in Ukraine,” said UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, although the “one voice” claim would seem to be stretching the facts somewhat. “As I have often said, the world must come together to silence the guns and uphold the values of the UN Charter. I welcome this support and will continue to spare no effort to save lives, reduce suffering and find the path of peace,” said Guterres in a statement. His determination is admirable. Guterres had visited both Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, in April, although his talks with Putin were said to have been “chilly” and a physical distance was maintained between them throughout.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres with Volodymyr Zelenskyy, President of Ukraine in Kyiv, 28 April 2022© President.gov.ua

Back in February, a UN Security Council resolution, condemning Russian aggression in Ukraine, was blocked by the Russian envoy. He dismissed it as “anti-Russian” but also claimed it had been “anti-Ukrainian”, because it was not in the interests of the Ukrainian people.

It’s hard to imagine that he thinks bombings, shelling and widespread destruction are in the Ukrainian people’s interests, but one must assume he does, unless he simply means that an early surrender would save lives. It comes under the same heading as the claim by the President of Russia’s parliament, the Duma, that supplying arms to the Ukrainian military should count as a ‘war crime’, on the basis that it is extending the war.

Or, to put it another way, delaying a Russian victory and the extinction of Ukraine as an independent nation.

NOT PERFECT BUT SPECIAL

It’s worth asking ourselves, after three quarters of a century, if the United Nations organisation has made a significant difference to people’s lives. I’m inclined to grant it the sort of comment that was sometimes written in my school reports: “could do better”. It’s very far from perfect but the world would be a worse place without it. Since its foundation in 1945, in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, it has concerned itself with a number of important issues: decolonisation, economic and social development, human rights, and the environment. An attempt to ban nuclear weapons still awaits ratification by any nuclear power. In any uneasy crowd, the people holding the biggest sticks are always going to be reluctant to give them up. So, the UN is not perfect – far from it, as Russia’s continuing war in Ukraine proves – but as Bob Marley, the Jamaican Reggae singer, musician and songwriter, said: “The most beautiful things are not perfect, they are special.” No-one could say that the UN isn’t “special”.

For one thing, it helps to establish and maintain peace. Since 1948, the UN has helped to bring conflicts to an end all over the world, such as in Cambodia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mozambique, Namibia, and Tajikistan. According to the UN’s own website, its peacekeeping efforts have also made a big difference in, for instance, Sierra Leone, Burundi, Côte d’Ivoire, Timor-Leste, Liberia, Haiti and Kosovo. To quote the website: “By providing basic security guarantees and responding to crises, these UN operations have supported political transitions and helped buttress fragile new state institutions. They have helped countries to close the chapter of conflict and open a path to normal development, even if major peacebuilding challenges remain.” The UN admits, however, that not everything has gone quite the way it intended, on those occasions when: “UN peacekeeping – and the response by the international community as a whole – have been challenged and found wanting, for instance in Somalia, Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.” However, the UN says it learned from these setbacks, which: “provided important lessons for the international community when deciding how and when to deploy and support UN peacekeeping as a tool to restore and maintain international peace and security.”

Take a look at Côte d’Ivoire, for example, which in 2004 was divided in half by a civil war. There were presidential elections in 2010, during which some 3,000 Ivorians were killed and around 300,000 became refugees because of the ensuing conflict. Instructed by the Security Council, the UN deployed more than 6,000 peacekeepers in 2004 , increasing that number to 11,792 in 2011. Their presence facilitated further presidential and legislative elections in 2011 and 2016, and in that second election the opposition took part for the very first time. Voting for and against your representatives is a much better route to peace than by siting them along the barrel of a gun. Human rights abuses were greatly reduced through the work of the National Commission on Human Rights, with a reported 1,726 abuses in 2011 cut to just 88 in 2016. That’s still 88 too many, of course, but it’s a big step in the right direction. Furthermore, 70,000 combatants were disarmed and re-integrated into civil society, a quarter of a million refugees were returned to their homes by 2016 and, better social cohesion was supported through 1,000 ‘Quick Impact Projects’, which reduced inter-communal conflicts by 80%. Of course, it doesn’t mean that old enmities were forgotten and they “all lived happily ever after”, as people do in fairy tales. People don’t forget those resentments, but in time they become fireside tales told by grandparents to small children, while having fewer combatants means more people to till the soil and plant and harvest crops. The peacekeeping forces saw the administrative part of the Ivorian administration spread across the country so that it is now present in all 108 local departments, with security forces made up of a 23,000-strong army, 19,000 in the gendarmerie and 18,000 police. With peace and security restored, Côte d’Ivoire is now one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies, with a growth rate of more than 9%. I’d say that’s definitely “special”.

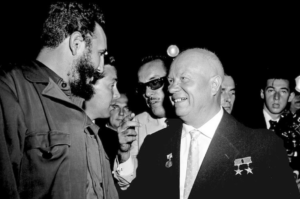

But it hasn’t all been a catalogue of remarkable achievement. The Soviet Union, as it was back then, ignored the UN’s views on Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The UN did nothing much about Israel’s aggressive activities in the Middle East, and it did very little over the Cuban missile crisis, when a secret deal between Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and the Cuban premier, Fidel Castro, could have seen nuclear missiles deployed on the island. Those with good memories may recall Khrushchev addressing the General Assembly at one time and taking off one shoe to bash on the podium to emphasize his point. Few remember what the point was, but many remember the shoe. Indeed, several launch sites were under construction on Cuba when President Kennedy decided to ignore his pugnacious advisors (many of whom favoured an invasion of the island) and put it into “quarantine”. He also warned Khrushchev of the possible outcome. The USSR and Cuba backed down, eventually. The UN had done virtually nothing, however, a response it repeated over Vietnam.

Looking back at those parlous times, it’s hard to see how we all emerged virtually unscathed from it (although the Vietnam War inspired some of the 1960s’ best protest songs; my favourite was “The Vietnam Song” by Country Joe McDonald and the Fish, which they performed at the Woodstock festival in 1969). The UN was equally ineffective at restricting the spread of nuclear weapons through what’s called “horizontal expansion”, and it has often expressed its support for democracy while itself being relatively undemocratic. It has proved itself unable to restore trust after the US invasion of Iraq in a fruitless search for non-existent ‘weapons of mass destruction’.

These and other examples of inactivity and misjudgement raise the question of just how “special” the UN really is. I suppose it would be fair to say that it may not achieve much but that even less would be achieved globally were it not there.

WHOSE SIDE ARE YOU ON?

A complaint that has been levelled against the UN is that it is too financially dependent on the large, industrialised nations (especially the United States), which has led to it lacking impartiality and neutrality when a crisis arises. That tends to erode trust in its judgement, especially among the poorer nations. Meanwhile, various diseases continue to spread, despite the UN’s best efforts. The spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus can hardly be blamed on the UN, but it could have done more, some argue, to halt the spread of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases and infections (STDs and STIs). AIDS is a difficult one, and much harder to deal with, but it has been estimated that every day around the world a million more people develop a sexually transmitted infection of some kind. It’s not always through the act of sexual intercourse, either; some of them can be passed on by skin touching skin, which means that a condom won’t necessarily save you. Gonorrhoea rates for adolescent boys aged 15–19 have reached a disturbing 220.9 per 100,000 male respondents, while around a million pregnant women suffer from syphilis. Any man tempted to pay for sex should remember that around 50% of sex workers (prostitutes) have gonorrhoea (commonly known as “the clap”, or more colourfully in the 18th century as “Cupid’s measles”), and that most STDs don’t produce easily recognisable symptoms, at least not quickly.

What other examples of UN failure could be cited? Take the hijacking by Palestinian terrorists of El Al flight 426 in 1968, often said to be the first of the modern terrorist attacks. The UN condemned the attack but did nothing about it. It took the 9/11 attack in New York in 2001 before terrorism was officially outlawed, although it was only Al Qaeda and the Taliban that were named. The Taliban, now back in control having told women to wear the veil at all times and not to be seen in public, would have horrified Amanullah Khan (ازی امان الله خان), the Afghan king who thew off British colonial rule and strove to move his country into the 20th century. He was a monarch who had been influenced by Soviet thinking, as well as by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and who had little time for his country’s religious fanatics. He also retained some admiration for Britain. Amanullah was much admired during a state visit to Egypt as the only Muslim monarch to have made a European colonial power back down. But he saw no reason for women to cover up or wear a veil, nor for men to wear beards. He fined anyone caught wearing a turban. When he made his declaration about the veil during a long lecture to his people, his queen Soraya stood up and removed hers. It was the first time that Afghans had seen any queen’s face, let alone their own queen’s. Several other women did the same and Amanullah introduced education for women, including the learning of foreign languages. When religious leaders told him that women must wear veils, Amanullah asked them where that was written in the Qu’ran, knowing that it is not written there or anywhere. Strangely, some religious Muslims sided with the colonialists, hoping the British would help them to counter what Osama Bin Laden would later call “the near enemy”: secular Muslims and modernisers. Religious extremists started a rumour at the time that he planned to make soap from the bodies of dead religious Muslims and these ludicrous rumours still surface from time to time. That, of course, began before the UN existed and it’s not the UN’s fault that such silly fantasies still circulate.

But remember: the UN had not outlawed other terrorist groups. Amanullah’s successful visit to Soviet Russia was facilitated by his friendship with Vladimir Lenin, who had hailed him as “a brother”.

The UN was not very successful in curbing the spread of nuclear weapons. Only the United States had one when the UN came into being in 1945, but others were not far behind. The Soviet Union, of course, in 1949, plus the old colonial powers of Great Britain (1952) and France (1960). China had one by 1964 (it now has lots, it seems) along with India (1974), Pakistan (1998), North Korea (2006) and Israel (date unknown, but some time between 1960 and 1979). A single modern nuclear weapon has power equivalent to 100,000 tonnes of TNT or more, which, if detonated in a densely populated area, could kill more than half a million people. The only country to threaten the use of such a weapon recently is Russia, with Putin saying he would use one on countries that supply weapons to Ukraine. That’s no way to become more popular. It’s an extreme response, not unlike someone who, when losing a game of chess, throws the board to the floor and stamps on the pieces. Logical, reasonable behaviour is not what we expect from Putin, I’m afraid.

The UN also failed to put a stop to a very bloody civil war in Sri Lanka, which began in 1983 and didn’t end for 26 years, with the separatist Tamil Tigers fighting for the independence of their region. Almost 200,000 people were forced to flee the fighting and the UN’s Human Rights Council (HRC) was urged to investigate allegations of war crimes. A supposedly ‘safe zone’ was declared along the heavily populated northeast coastline but it didn’t work: between January and the end of April 2009, more than 6,500 people were killed there. The UN failed to intervene. The then Secretary General of the UN, Ban Ki-Moon admitted he was “appalled” by what he saw there.

Nor were the famous “Blue Helmets” – regular soldiers drafted in to support the UN – much of a reassurance in such places as Bosnia, Kosovo, Cambodia, Haiti, and Mozambique, where child “prostitution” soared. There is a strong suspicion that soldiers who had raped a young girl would then give her a candy bar or a very small sum of money, so that it would be seen as a commercial transaction, rather than an act of sexual violence. But rape is rape, candy bar or not. It is never excusable. Most people would, I hope, agree that Stalin’s greatest general, Georgy Zhukov, was wrong to condone the mass rapes carried out as the Red Army swept through Hitler’s Germany and into Austria, however horrifying the actions of the Nazis had been. The use of vetoes in the UN Security Council is also disturbing, as I mentioned earlier. The Security Council has fifteen members, five of them permanent – France, Russia, China, the United States, and the United Kingdom, but ten more members are then elected to bring up the total to fifteen, each serving two-year terms, and resolutions have to be passed unanimously. The five permanent members can thus veto any proposal, even if all the other members leap up and down in ecstatic acceptance (that would be something worth seeing). China and Russia have both used that power, most recently of course with Russia vetoing criticism of its invasion of Ukraine and the demand for its immediate withdrawal. It happened in 2012, too, when the Security Council tried to use sanctions under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter to intervene in Syria and prevent a bloodbath. China and Russia successfully halted international intervention there, since when some 60,000 civilians have been killed and thousands more displaced.

THERE’S NO-ONE MORE PEACEFUL THAN THE DEAD

The UN’s supposedly good intentions were also thwarted in 1995 with the Srebrenica massacre, also known as the Srebrenica genocide. It happened during the Bosnian war, with Serbs targeting Bosniaks, who were mainly Muslim. The UN designated Srebrenica a “safe zone” in 1993, but it wasn’t. Militarised units were obliged to disarm and a UN peacekeeping force of some 600 Dutch soldiers was put in place, but they were surrounded by Serbian soldiers, tanks and artillery, cutting off supplies. Serbian forces advanced, forcing the UN team to withdraw. Some 20,000 Bosniak refugees fled to seek protection from the Serbs, but the Serbs entered the camp anyway, raping the Bosniak women and murdering at will, while the Dutch troops did nothing, although they had been ill-prepared and poorly equipped. By July that year, 7,800 Bosniaks were dead, making this the worst single act of mass murder on European soil since the Second World War.

For an example of UN failure, you should take a look at Cambodia in the 1970s. Remember the Khmer Rouge? Their peculiar version of Communism involved the mass killing of those who disagreed with their leader, Pol Pot, who appears to have been a psychopath. He had ordered the “executions” (which were murders in reality), which led the Vietnamese army to invade and remove him and his forces. Pol Pot was sent into exile and a new government was put in place, but the UN refused to recognise it because of the recent war between Vietnam and the United States. Instead, the UN recognised the Khmer Rouge as the proper Cambodian government, even though they had killed some 2.5-million Cambodians, roughly a third of the country’s population.

The UN has failed even to try to uphold the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). During the Cold War, the UN did and said nothing when countries in the Soviet bloc crushed moves to uphold the UDHR by force. It failed to do anything when Sudan attacked non-Arabs and its government created the so-called Janjaweed terrorists, who attacked peaceful villages, using artillery and helicopter gunships, while Sudan’s military painted their aircraft white so that people would think they were from the UN. Between 2003 and 2010, some 300,000 Sudanese civilians were killed by their own government. The genocide in Rwanda was another example of inaction and ineptitude on the UN’s part. The Canadian Commander there warned the UN that Hutu mobs planned to kill members of the Tutsi minority, but either the cable didn’t arrive or it was ignored. The UN team was not authorised to use military means to keep the peace. After the deaths of eighteen US soldiers in a battle at Mogadishu, the United States was unwilling to supply more assistance in any case. Belgian peacekeepers abandoned a school they were supposed to be protecting after ten of their soldiers were murdered, and thousands of Tutsis who sought sanctuary there were slaughtered by the Hutu mobs. In the end, one in five of the population were killed; close to a million people. It was not the UN’s finest hour.

WHERE TO NOW?

So, there we have it: an international organisation set up to prevent war after the biggest war in history. It was supposed to set certain standards and to defend them, by force if necessary. An admirable intention with some remarkable successes to its name, but also with some lamentable failures to spoil its record. Human nature is not always kindly, thoughtful or selfless. It’s impossible, of course, always to be right, to take the best decisions in a suitably resolute manner and always to act accordingly, so in the case of the United Nations we have to weigh up the pros and cons and see if there is a way to renew it, perhaps even to relaunch it, in a manner that is more foolproof and successful and less likely to make a mess of things. One thing is certain: however good it is, it won’t please everyone. The UN celebrated its 75th anniversary last year, and with the Second World War having receded into the ever-more-distant past, we must ask ourselves if it can – and should – continue. In a report published to mark the anniversary and lay out proposals for the way ahead, Secretary General Antonio Guterres spoke about “our common agenda”.

When he launched his report in September 2021, he began with a scathing critique of the world in which we live. There was, arguably, a more universal devotion to the UN’s founding principles in the beginning, when it was new. But as we also know, it didn’t last and in some areas it didn’t really work. Yes, it would be wonderful if all the nations of the Earth agreed to work together towards a common peace, with better health, a more caring society, greater environmental awareness and less selfish greed, reduced paranoia about other people and groups and less inclination to dislike those we each, in or own ways, see as “other”. “From the climate crisis to our suicidal war on nature and the collapse of biodiversity,” Guterres warned, “our global response is too little, too late.” Since we do not yet have a way to time-travel and turn back the clock, we are where we are and have done what we’ve done. It may be too little, too late, but we have to do something, don’t we? “Unchecked inequality,” Guterres warned, “is undermining social cohesion, creating fragilities that affect us all.”

Technology is moving ahead without guard rails to protect us from its unforeseen consequences.” He said that we face two alternative futures: one of “breakdown and perpetual crisis, and another in which there is a breakthrough, to a greener, safer future.” In his doomsday version, he described a world subject to a SARS-CoV-2 virus that is forever mutating to become evermore infectious and deadly, because the rich countries hoard vaccines, allowing health systems to become overwhelmed. In that scenario, our planet becomes uninhabitable with rising temperatures and extreme weather events pushing millions of species to the brink of extinction. It would also lead to the erosion of human rights, disappearing jobs, mass poverty and unrest, with violent repression to keep things in order. The alternative direction, he believes, would mean the equitable sharing of vaccines, a sustainable and largely decarbonised economic recovery helping to put the brake on global temperature rises, and with vulnerable groups protected. It sounds like a form of utopia, but it’s not beyond our grasp if we work together. Guterres wants to see a “Summit of the Future”, which would (or could, at least) “forge a new global consensus on what our future should look like, and how we can secure it.” All those long-dead fish, seaweeds and crustaceans are best left where they are, deep underground or undersea (or both). At the COP26 conference on climate change, held in Glasgow, Scotland, last year, Guterres was as outspoken as usual: “We are digging our own graves by treating nature like a toilet,” he told the delegates. “The six years since the Paris Climate Agreement have been the six hottest years on record.”

It’s not the only solution, of course. We can all stop using gas, oil and coal (difficult though that will be) but it’s not the crock of gold at the end of the rainbow. The magazine Nature suggested last year that the rich countries should donate $100-billion (€94.7-billion) a year to poor nations to help them to cope. It now thinks it underestimated: “Trillions of dollars will be needed each year to meet the 2015 Paris agreement goal of restricting global warming to well below 2 °C, if not 1.5 °C, above pre-industrial temperatures,” the magazine says. “And developing nations (as they are termed in the Copenhagen pledge) will need hundreds of billions of dollars annually to adapt to the warming that is already inevitable.” Brazil’s right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro apparently wants to cut down the Amazon rainforest upon which his indigenous people depend, and it appears to involve the use of fire. Smoke from the Amazon’s fires can be seen from space. To people like Bolsonaro and his supporters, it would appear that profit is more important than a sustainable and healthy environment. But there again, he doesn’t believe in climate change and has accused his critics of being “agents of foreign powers.” All of this does not bode well for our poor, beleaguered planet. The UN’s rôle in preserving our world, as far as possible, will be vital, although it probably means taking on the far right, who don’t seem to believe the problem exists. When I was a child I used to read the comic (long gone) called ‘The Eagle’, featuring the comic-strip spaceman Dan Dare. In one of the stories, Dare was trying to save the planet from people who were unaware that their devotion to plant life would kill off the human race. Of course, good old Dan succeeded, despite some pretty nasty enemies. Let’s hope Guterres does, too.