Us troops in Afghanistan © Dod

In the years immediately following the world’s deadliest-ever conflict, World War II, the European Union was born as the European Coal and Steel Community. Its aim was to place what were seen as the instruments of conflict – energy and raw materials for armaments – under common control, thus (it was hoped) rendering the possibility of another international conflict on a similar scale on the continent of Europe less likely, perhaps even impossible. It also provided, in the words of the European Commission’s most famous and arguably best-ever President, Jacques Delors, “a bold initial impulse for European integration”. In theory, little has changed. “Today’s European Union (EU) is based on treaties negotiated and ratified by the member states,” wrote Finn Laursen in his article entitled ‘The Founding Treaties of the European Union and Their Reform’ in the Oxford on-line Research Encyclopaedia.

“They form a kind of ‘constitution’ for the Union.” Laursen goes on to explain: “The first three treaties, the Treaty of Paris, creating the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951, and the two Treaties of Rome, creating the European Economic Community (EEC) and European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) in 1957, were the founding treaties.” Their aim was peace and prosperity in a Europe which had just witnessed a conflict in which up to 85-million people had been killed.

The originators of the plan clearly hoped it would develop further. France’s Foreign Minister at the time, Robert Schuman, told the meeting, which was held in the Salon d’Horloge at his Quai d’Orsay headquarters in Paris, that it would be “the first concrete step towards the federation of Europe.” Wishful thinking, I’m afraid. It looked like a sound idea, and it was, although even then it failed to find acceptance in the argumentative UK. “Oh, no,” responded Emmanuel (Manny) Shinwell, the Labour government’s Minister of Fuel and Power, when the idea was put to him in a London restaurant where he was having dinner, according to Dirk Spierenburg, (who would go on to become a member of the new European Coal and Steel Community’s High Authority, forerunner of the European Commission), “the Durham miners would never forgive us.” No-one ever asked them, of course.

Their opinions may not, in fact, have counted for very much in Westminster’s corridors of power at any point in my lifetime, (and now that all the coal mines are closed, not at all) although the annual Miners’ Gala parade through the beautiful old city of Durham, with its many brass bands blowing triumphantly as the participants march up to the city’s superb 11th century cathedral and then on to the County Hotel, on whose balcony sit the big name VIPs, still attracts quite a crowd, at least some of whom must remember when miners were powerful. Interestingly, and despite representing the constituency of Sedgefield, which is sited at the heart of the Durham coalfield, former Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair never attended one. What a shame: they’re splendid events.

But I’m wandering from the point here. We’re not talking about pacifist post-conflict dreams of European nations co-operating without a squabble. No, we’re looking at Afghanistan. Recent events there have shocked many and almost certainly changed the ground rules. As France 24 put it: “European countries had no option but to pull out of Afghanistan along with the US – despite their desire for Western troops to stay and stop the country falling into the Taliban’s hands.” But pull out they did, leaving that sorry country’s citizens in the power of some very nasty and unreasonable people, previously led by Mullah Omar who claimed to be ‘God’s deputy on Earth’ (no-one asked God’s opinion).

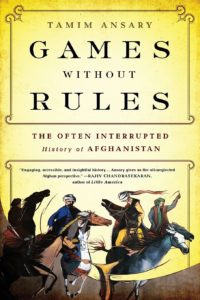

This would have come as no great surprise to Tamim Ansary, writer of an excellent brief history of Afghanistan, his native country: ‘Games Without Rules’. “Five times in the last two centuries,” he wrote, “some great power has tried to invade, occupy, conquer or otherwise take control of Afghanistan. Each intervention has led to a painful setback for the intervening power, and the curious thing is, these interventions have all come to grief in much the same way and for much the same reasons – as if each new power coming into Afghanistan has vowed to take no lessons from its predecessors.” When I was there and crossing (illegally) over the border from Pakistan, the tailfins of a Soviet missile were still protruding from the roof of the wrecked post office at Torkham, just beside the border, while some market stalls in Peshawar, on the Pakistan side, were selling items of plundered Russian military uniform and equipment, just to help emphasize who had won.

TANKS FOR THE MEMORY

Getting the member states of the EU to agree on anything is a Herculean task. They have agreed to co-operate on various issues in the past but often don’t when it comes to the pinch. When it comes to matters of mutual defence, the Secretary General of NATO, Jens Stoltenberg, believes that it often comes down to misunderstanding. Stoltenberg supports European defence, he says, “but at times you get the impression that strategic autonomy or European Defence, with a capital E and D, is something outside, alternative to NATO. And that I don’t support.” NATO has been central to European defence thinking for decades, despite (or perhaps because) it makes Russia uneasy. It seems that the EU would have to depend on NATO to undertake any military missions on its behalf, rather than have a separate military body. Furthermore, even if some of the more bullish leaders of EU states were to allocate troops and matériel to some new, as-yet unspecified force, who would pay for it? How would the additional costs be allocated fairly? “There is no way you can get more European defence without European Allies spending more,” said Stoltenberg at a recent session of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly, “And there is one institution that’s been pushing for more European defence spending for years, and that is NATO.” In the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, with budgets stretched and supply chains badly disrupted, the prospect of higher spending to cope with no immediate emergency is unlikely to garner much support.

There is a provision in the EU’s rules for the creation of what is, in effect, an EU army. It’s called the European Defence Agency (EDA), set up under the Lisbon Treaty. The EDA was established by the Council of Ministers on 12 July, 2004, “to support the Member States and the Council in their effort to improve European defence capabilities in the field of crisis management and to sustain the European Security and Defence Policy as it stands now and develops in the future”. Its aim, it makes clear, is to do with preserving the peace. The original ‘Joint Action’ that created the EDA was replaced in 2011 by a Council Decision in 2011 (further revised in 2015), with the aim of supporting the development of the EU’s defence capabilities and enhancing military cooperation. It was also intended to stimulate defence research and technology to boost Europe’s defence industries, while serving as an interface with the EU’s wider policies.

On its own website it describes its purpose: to act as a catalyst, promoting collaborations, launching new initiatives and improving Europe’s defence capabilities. “It is also,” it says, “a key facilitator in developing the capabilities necessary to underpin the Common Security and Defence Policy of the Union.” Among the conclusions and recommendations of a review in 2017, the EDA stated that one of its principal aims is: “To acquire and maintain key capabilities, Member States will need to further enhance defence cooperation. In their “Bratislava Declaration” of September 2016 Heads of State and Government highlighted the Bratislava Roadmap and its call to strengthen cooperation on defence and to make better use of the options in the Treaties, especially as regards capabilities.” With so much intellectual effort around the world being devoted to developing advanced weapons systems, the EDA also has to keep up with developments. “One of the main tasks of the Agency,” it says on its website, “is to support the Member States in the development of cooperative defence capability projects in the air, land, maritime, cyber or space domain.” Training courses have focused, among other things, on carrying out airlifts, the use of helicopters, identifying and neutralising improvised explosive devices (IEDs), the use of drones and organising cyber defence.

NATO, meanwhile, has recently been testing new technologies to counter the threat from drones. It is working with industry and carried out a trial of various counter-drone technologies at an airbase in the Netherlands in an exercise called C-UAS TIE 21 (it stands for Counter-unmanned Aircraft Systems Technical Interoperability Exercise; the military seems to like long, complicated terms). In the exercise, specialists from the civilian, military, scientific and industry worlds cooperated to come up with a solution.

Europe’s capabilities are often compared unfavourably with those of the United States, but that may be unfair: the USA is one large country, the states of which are sometimes less united than the name suggests, while the EU comprises twenty-seven quite individual member states, not all of them even speaking the same language and often disagreeing about their history, too. Stoltenberg spelled out the situation at the same Parliamentary Assembly meeting, defining it as ‘fragmentation’. “In the United States,” he told the Assembly, “there are many thousands of battle tanks, and there are only one type. In Europe, we have fewer battle tanks, and there are seventeen different types,” The United States uses the M1A1 Abrams or its M1A2 variant, of which some 9,000 have been built. Estimates of the numbers in service vary but it could be around 6,600. In Europe, there are some fourteen different Main Battle Tanks (MBTs), although some of them are just variants of other models. MBTs would be vital in any conflagration across the EU, it being a land mass and, for much of it, relatively flat.

France, which seems to be keenest on having an EU army, sees the EU and NATOs eastern flank as a vulnerable area, and has done so since the Crimean crisis of 2014. France’s next tank is seen as being an element in the Main Ground Combat System (MGCS). The current Leclerc MBT looks certain to be replaced. The MGCS is supposed to have inter-operability facilities which the French favour, but the Germans fear could be too complicated and thus possibly vulnerable, although there’s an awareness that the German-built Leopard 2, the de-facto MBT of choice throughout Europe, will have to be replaced in the not-too-distant future.

In planning for possible future conflicts, we have to bear in mind that while the French (like the Poles) still see Russia as the greatest threat, Italy is still concerned about the possibility of conflict among EU member states. Italy’s MBT fleet currently includes two hundred of its home-built C1 Ariete tanks. Britain still relies on the Challenger, currently in its third iteration as the Challenger III. Having so many different types presents the potential for mix-ups with spare parts. Carrying everything that might be needed with a European combat group would certainly be a challenge.

It may not count for much in the long run, though: Russia can boast a total of 12,000 MBTs – twice the number that the United States has. Incidentally, the most rapid development of more advanced MBTs has been carried out by Russia and Israel, despite British Eurosceptics insisting that the UK must be prepared to defend the sceptred isle against those who eat croissants, panettoni and sauerkraut. But the devoted Europe-haters will always trot out these arguably childish neo-nationalist notions.

ASSEMBLING THE PIECES (if they fit)

Europe’s armaments industries are fragmented, and so, too, are their products. That is a worry because there would appear to be an arms race in progress that nobody can easily win. “NATO-EU cooperation has already reached unprecedented levels,” Stoltenberg told a meeting of NATO Defence Ministers in October 2021. “In cyber space, we exchange information on threats and vulnerabilities in real time. In the Aegean Sea, our maritime mission works with the EU to implement their agreement with Turkey. And in Kosovo, NATO troops “stand shoulder-to-shoulder with EU diplomats” (wearing combat gear and armed with reinforced fountain pens?) “to bring peace and stability to the region.” He also spoke about “strengthening cooperation in other areas, such as military mobility, resilience, emerging and disruptive technologies, and the security impact of climate change.” But how does he feel about the arguments put forward by some EU leaders for going further? He told delegates that he welcomes the EU’s “increased efforts on defence” but added that “These efforts should not duplicate NATO. What is needed is more capabilities, not new structures.”

Writing in an on-line article for the Instituto Affari Internazionali, Alessandro Marrone and Ester Sabatino urged military authorities to update their arsenals before it’s too late. “The new MBT’s characteristics require a greater technological effort than in the past, ranging from active protection systems to gun, turret, vetronics (vehicle electronic architecture) and optronics, and particularly to automation. Yet MBTs in European inventories are often outdated and their readiness level is low.”

They note that France and Germany launched a joint project in 2017 to develop and produce a next generation Main Ground Combat System (MGCS). Italy and Poland have repeatedly asked to join the MGCS cooperation, yet Paris and Berlin apparently want to keep it exclusively bilateral until a prototype is developed. After that, who knows? Therefore, Italy must choose from among a limited range of options in order to satisfy its army’s MBT needs, as well as maintain a reasonable level of technological sovereignty in this sector. Of course, under the Common Security and Defence Policy of the EU, there already exist two types of EU multinational forces, set up either inter-governmentally and made available under article 42.3 of the Treaty on European Union such as the Eurocorps, or else the EU Battlegroups, which were set up at EU level. The Battlegroups stem from the contributions made up through a coalition of member states.

The EUBG is to be deployed in a distance of 6.000 km from Brussels. It is to be capable of achieving initial operational capability in theatre within 10 days after decision of the European Council has been taken to launch the operation.

There are eighteen altogether, each providing a battalion-sized force of 1,500 soldiers, together with combat support teams. The groups rotate and are kept in readiness for instant deployment under the control of the Council of the European Union, made up of member state ministers and prime ministers. Although they were ready for combat by the start of 2007, they have yet to see action. Some have called them the EU’s “standing army” but that is a bit of a misnomer. They’re really more of a fail-safe provision, just in case of unforeseen emergencies. In any case, the most rapid technical advances in the design and construction of tanks comes from Russia (probably no surprises there) and Israel.

Reports about a possible EU army were raised by Euro-sceptics during the long discussions surrounding the UK’s referendum on remaining in the Union. Most of the quotes you will find on-line are from nationalist right-wing newspapers which are relentlessly anti-European. Certainly, the issue of an army to give the EU more clout has been discussed over the years; I watched some of the debates myself from the press seats. Debates among members of the public have also been held on the Internet, with the majority usually being against the idea, if not by very much. For instance, one organised by Debate.org, which showed arguments on both sides, claimed that only 44% want a European army. We must assume (the website doesn’t state) that 56% don’t, although I suspect the numbers taking part were relatively small and therefore possibly unrepresentative.

According to the political magazine The Week, which wrote in 2018: “In November, French president Emmanuel Macron warned that Europeans cannot be protected without a “true, European army” to defend the EU from China, Russia and even the US.” Really? In the past, the former German Chancellor Angela Merkel has backed the idea. The article goes on to cite the ways in which the idea has been used to scare British voters and persuade them to leave the EU. It stresses that “The Centre for European Reform said in 2016, that ‘Britain’s Eurosceptics have spent years frightening people with the idea of an EU army’, and that ‘conspiracy-minded Brexiters insist that, were the UK to stay in the European Union, British troops might soon be faced with conscription into a Brussels-controlled army’.” It shows great imagination, at least, but also very little knowledge of how the EU works. One contributor to this debate was horrified at the thought of “British troops” being “called up to fight in a Brussels-led army.” Those of us familiar with how the union and its various institutions work may find the idea vaguely amusing but not under any circumstances likely.

The Week magazine quotes Macron as saying that no country can tackle today’s security threats on its own. “The French president said that Europeans can no longer rely on the US to defend them in response to President Donald Trump’s decision to pull out of a landmark 1987 nuclear treaty with Russia that effectively protects Europe from nuclear weapons.” In an interview on the French radio station Europe 1, he went further: “I want to build a real security dialogue with Russia, which is a country I respect, a European country – but we must have a Europe that can defend itself on its own without relying only on the United States.” The significant thing here, I think, is that without American air power, Europe felt it couldn’t leave any troops in Afghanistan, much as it wanted to. France in particular was furious and emerges from the whole debacle with the most credibility.

POLITICAL POT-SHOTS

The European Parliament debated the whole issue in May 2021. Debates held in the European Parliament are generally speaking quite learned affairs, whatever the UK’s right-wing press may say, with quite a few members having a store of expert knowledge gained in former posts. In 2017, a Eurobarometer report on security and defence showed 75% of those members of the public who were questioned favouring a common EU defence and security policy, with a far smaller majority – 55% – wanting to see an EU army. In an address to the European Parliament, Merkel told MEPs “We ought to work on the vision of one day establishing a proper European army.”

A security and defence union has also been one of the goals of Ursula von der Leyen’s Commission. In fact, the Treaty of Lisbon states the need for a common EU defence policy, but it also stresses the importance of national defence policies. Some EU member states are obliged under their constitutions to observe neutrality: Austria, Ireland, Finland, Malta and Sweden. Their forces (and they all have some) would never join in an EU military operation. It’s not clear that many of the others could afford to: despite agreeing at a NATO summit in 2014 to spend 2% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on defence by 2024, with the European Parliament urging them to live up to their promises, only Greece, Estonia, Latvia, Poland and Lithuania have done so.

MEPs have repeatedly called for all member states to live up to their Lisbon Treaty promises in moving towards a European defence union. They have, on several occasions, called for better and closer cooperation, and for the pooling of military and strategic planning resources to create what they have called “synergies at EU level in order to better protect Europeans.” There is, however, the problem of different traditions and cultures that complicate full cooperation. In a straight comparison between the European Union and the United States, for example, in 2014 the EU had the highest GDP at €14,000,671, compared with €13,111,780 for the United States. But of course, it’s not just a case of how much you spend; it matters how you spend it. The US spends 4% of its GDP on defence, while the EU, taken as a whole, spends just 1.3%. Of that, 51% of the EU’s defence spending is on staff and just 19% on investment, including research, procurement and development. For the US, just 33% goes on staff, with a whopping 29% going on research, procurement and development. Europe’s fighting forces are greater: 2,149,800 people under arms, compared with the 1,381,250 in the US. The EU spends €23,829 per soldier on research and development, while for the US the figure is €102,264. The EU’s forces also use a bewildering variety of types and makes of weapons, totalling some 154 in all, whereas for the US, it’s just 27. Research for the European Parliament suggests that if all EU countries used the same ammunition certification system it would save €500-million.

Similarly, the EU has 17,160 individual armoured personnel carriers (APCs), but they come in 37 different types. That’s a lot! The United States has far more individual APCs: 27,528. Even better, they come in just 9 different types. The same pattern emerges for air refuelling tankers: for the EU, just 42 aircraft but in 12 different types. The US has a massive 550 tankers, giving its forces worldwide reach, but despite the numbers, they come in just 4 types. It’s a similar picture where combat aircraft are concerned: the EU has 1,703, but they come in 19 types, while the US has far more – 2,779 – and there are only 11 types. I stress again that these are figures from 2014. It helps explain why EU countries felt they had to leave Afghanistan when their US allies did. 68% of EU citizens say they think that the EU should do more in connection with security and defence policy; up from 66% just two years earlier. Europeans, it seems, expect their countries’ leaders – and the EU itself – to protect them from predatory countries, of which, as we know only too well, there are several.

The European Parliament has been told that EU countries waste some €26.4-billion each year through duplication, over-capacity and various barriers to procurement. The EU could provide the basis for far greater liaison and cooperation. As it is, Europe has six times as many defence systems as the US, most of them incompatible with one another. Getting a perfect match is important. Back in my youth, when I was a member of a target shooting club and held a British firearms certificate and a Husqvarna Lahti pistol, I witnessed what happened when the owner of a 9mm Walther P38 handgun used Mark 2Z ammunition. It was designed for sub-machine guns, not handguns, being significantly more powerful and therefore more damaging to the pistol in which it was used (the ‘Z’ indicates that the rounds are loaded with a nitrocellulose powder, rather than Cordite. So does the Mark 1Z but it uses less of it). However, the shooting club had access to a cheap supply of Mark 2Z rounds and those of us owning 9mm pistols took advantage of it. The Walther blew up in my friend’s hand, injuring him, and another round greatly damaged the pistol I was using, turning it into scrap metal, although I was unhurt. Getting the details right is important and also much easier with standardised matériel. For the US, Russia and China, that’s simple. For an EU made up of various competing countries it’s much more difficult and potentially dangerous.

The Begin Sadat Center for Strategic Studies (BESA) at Bar-Ilan University is not sure it’s even possible. In a report for BESA, Ted Bromund, Senior Research Fellow in Anglo-American Relations at the Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom in Washington’s Heritage Foundation, wrote: “Yes, Europe can have an army. But calling a thing an army does not make it one.” The variety of cultures and traditions, he argued, would make it virtually impossible. “An army must draw on a military culture,” he wrote. “European cultures are profoundly unmilitary.” He also draws attention to the fact that European countries seldom agree on very much, which would make a European armed force unwieldy. “An army must be sent by its national leaders to the battlefield,” he reminds us, “But Europe was split on the Balkans, Iraq, Libya, Georgia and Ukraine. When Europe does take action, it is belated, limited, and usually divided. Europe has few core interests in common, so it will not be willing to send an army in common.” He also suggests that “there are not enough Europeans who want to kill and die for Europe to form an army.”

I would suggest that few if any people join an armed force just because they want to kill someone and die in glory for their country. Those that do are usually (and correctly) labelled “terrorists”, trying to spread their extreme views by means of violence. So perhaps some sort of force that could be mobilised in support of EU countries might be possible after all.

“Within a scenario of growing geopolitical instability and rapid technological innovation in the defence sector, the EU has engaged consistently in building up its Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP),” writes Elena Lazarou, Senior Policy Analyst at the External Policies Unit of the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) in Brussels. “Some of its achievements so far in the area of defence are: the activation of permanent structured cooperation (PESCO); the establishment of military planning and conduct capability (MPCC); the coordinated annual review on defence (CARD); preparatory action for defence research; the European defence industrial development program (EDIDP); the new compact for civilian CSDP; plans for military mobility; and a dedicated European defence fund in the next multiannual financial framework.” If you read any of these reports, you have to be careful not to drown in a sea of acronyms. The same report also quotes Andrey Kortunov, Director-General of the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC) in Moscow. He believes the EU could assemble a powerful army but the fact that it has never done so, despite talking about it a lot, suggests that there is insufficient motivation to do so. “Nobody is eager to have a military machine in Europe duplicating NATO or even some of its functions,” he points out. Why? Here is his explanation: “Such a machine would be expensive, hard to manage, and politically risky for the transatlantic partnership – it might even provoke a US strategic disengagement from Europe. Second, it is not clear how a European army can respond to major EU security concerns.”

“The aim of an argument or discussion should not be victory, but progress,” wrote the French moralist Joseph Joubert. Where the idea of a European defence force is concerned there have been a great many arguments and some often quite forthright discussions, but although there has undoubtedly been progress, it has not been on an Earth-shattering scale. It’s a long time since the Treaties of Rome were signed but the idea of an army, recruited from all the member states, remains a matter of debate with no obvious solution in sight. Most of the news reports stating that a European army is just around the next corner come from the more nationalist journals, keen to pour a little more petrol on the fire of xenophobia to impress their supposedly “patriotic” (at least in their own eyes) readership. That means in other words those readers who love disliking foreigners. If such an army were to be created, who would have the final say on deployment? This doesn’t seem to be the kind of the decision that the European Council would relish. As we all know, the EU member states don’t always agree on everything and decisions can involve lengthy debates spaced over years. Armed conflict would seem to depend on the ability to take split-second decisions. What hope is there for an army that seeks consensus before shouting “charge”?

The idea that seems to have the most impetus behind it is the Initial Entry Force (IEF) first mooted in May 2021. It would come under the aegis of Strategic Compass Operations (SCO), currently under preparation by 14 member states, including France, Germany and Italy. The plan here is to reinforce the EU Battlegroup (EUBG) to enable the EU to respond more quickly in emergencies. Yet the EUBG has never been deployed in its 15 year existence. An IEF would not have helped in Afghanistan, according to Dylan Macchiarini Crosson, a researcher for the Centre for European Policy Studies. “The proposed IEF currently under member state consideration would not have been deployed (in time) to support the West’s retreat from Afghanistan. Nor would the IEF solve the root problems underlying the effective deployment of EU military forces and subsequently help make the EU a more capable global actor in the future.” There’s no nice way to put it, but Europe is too divided, its members too set in their ways, to suddenly provide an army that could stand against the world.

The Western Balkans remain an issue for EU defence ministers. Three of the Western Balkan states have been taking advantage of NATO’s mutual defence guarantee. They have shown considerable commitment to NATO by contributing to its operations, by hosting NATO bases and by committing troops to NATO missions in such places as Albania, Montenegro, and to North Macedonia’s contributions in Afghanistan. Kosovo also currently hosts a NATO mission, says CEPS, the Kosovo Force (KFOR), tasked with building the legal foundations and capacities of the Kosovo Security Force and supported by North Macedonia and Montenegro. Bosnia and Herzegovina would like to become full members but Republika Srpska (a sub-division of Bosnia-Herzegovina) won’t permit them to. Just to clarify this, Republika Srpska (Република Српска) is one of the two parts that make up Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. And as if that wasn’t complicated enough, there is also a city that has a special status and is not in either part, called the Brčko District. It gets more difficult still, with Serbia’s nationalist politicians putting out negative stories about NATO to keep their nationalist supporters suitably fired up. Prince Otto von Bismarck is claimed to have said towards the end of his life: “If there is ever another war in Europe, it will come out of some damned silly thing in the Balkans.” Let’s hope he was wrong.