© Fmn.dk

Looking at the world around us we may be tempted to despair; things are going wrong all over the place and in just about every conceivable way. One might be excused for thinking that some things never change. They do, however, and constantly. If you’re wondering why, the answer is the angular momentum of the Earth’s rotation, as viewed by an observer moving with it (mathematicians put it like this: ≈7.2×1033 Kg m2s−1, whatever that means). Well, that’s part of the answer anyway. We’re dealing here with angular momentum, the degree to which a body rotates, defined as the product of the moment of inertia (“I”) and angular velocity (“ω”).

The proper unit for Angular momentum is given as kilogram meters squared per second (kg m2/s). Angular Momentum formula is made use of in computing the angular momentum of the particle and also to find the parameters associated to it.

Wonderful thing, angular momentum.

Or consider entropy, generally regarded as the measure of a closed system’s disorder. In this instance, our planet, Earth, can be considered to be a closed thermodynamic system. Earth, having completed the accretion of matter that makes up the body of our planet, and its nuclear-generated energy having (more or less) settled down, will inevitably seek to achieve equilibrium with its surroundings; thus we get an increase in or maximisation of entropy. As the Science Direct website puts it: “Many focus(ed) on the gloomy picture of increasing disorder and thermal death, characteristic of equilibrium thermodynamics and isolated systems. In this regard, entropy is used to point out and measure the decreasing availability of high quality resources (i.e., resources with low entropy and high free energy), the increase of pollution due to the release of waste, chemicals, and heat into the environment, the increase of social disorder due to degraded conditions of life in megacities all around the world (well worth noting), the ‘collapse’ of the economy, and so on.” What I’m trying to say is that if you look up at the stars on any night, then repeat the exercise on the same spot night after night, you will never look up at the exact same view. Physics dictates that things move on and can never return to the exact same conditions that existed the last time you looked.

There is another way to put it using an expression that is familiar in English, known as ‘Murphy’s law’, which basically says that “if a thing can go wrong, it will go wrong”. Or, to put it another way, it all comes down to the Second Law of Thermodynamics: “The entropy of any isolated system never decreases. In a natural thermodynamic process, the sum of the entropies of the interacting thermodynamic systems increases.” In Boltzmann’s equation about entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics, that comes down to the following mathematical formula: S = KB log W (or Ω). In case you’re wondering, S is entropy, KB is the Boltzmann constant, (which equals 1.380649 X 10-23 J/K. The W stands for the probability (which in German is Wahrscheinlichkeit, hence the W) of a macroscopic state. To put it more simply, things may, if you’re extremely lucky, stay as they are, they will never become less messy and in most cases things will continue to get messier. And looking around our much-troubled world, we can see that is true. From the point of view of Vladimir Putin, things would seem to be getting much messier, Boltzmann notwithstanding, and he is the one responsible. He thought that by threatening other countries they would cave in to his ever-greater demands, but he was wrong. It’s made them take a tougher line instead.

Denmark has been a member of the European Union since January 1973, having joined at the same time as Britain and Ireland, but it has remained outside the Union’s “Common Defence Policy”, steadfastly clinging to its historical neutrality. Vladimir Putin changed the Danes’ minds by invading Ukraine. In a referendum, two thirds of the people voted to get rid of the opt-out from the policy: 66.9% chose defence over neutrality, which means that Danish officials won’t have to leave the room when their colleagues from other member states discuss defence-related issues. It will also mean that Danish armed forces will be able to participate in EU military operations and exercises. In campaigning for a “yes” vote, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen had told voters it would “strengthen our (Denmark’s) security”. With the outcome clear, Frederiksen said in a speech she gave in the capital, Copenhagen: “When there’s a war on our continent, we can’t be neutral. Maybe this is the biggest ‘yes’ in an EU referendum ever in Denmark.” Perhaps Putin will finally take note: Europe is not intimidated by bluster and threats, nor even by the arrival of his troops and their armoured vehicles. Based on past performance, he’s more likely to ignore it.

Back in 2016, anti-Europeans in the UK were predicting that Denmark would soon follow Britain through the exit door, but instead every region in the UK has said, in a variety of recent polls, that leaving Europe was a huge mistake, leading to higher prices and a shortage of labour and certain goods. The Danes have watched that happening, so the Danish referendum vote should come as no surprise, although Frederiksen admitted to her country’s parliament that many Danes are still opposed to the EU. She promised no more referenda on Denmark’s other opt-outs from EU treaties, such as the single currency and cooperation on justice affairs. The Danes voted not to join the euro in 2000, choosing instead to keep the krone (DKK) in virtual lock-step with it instead. Denmark’s Foreign Minister, Jeppe Kofod, has admitted to the media that there remain “a series of formal steps before Denmark can be admitted” to the common defence policy but Mette Frederiksen said the results represent “a clear signal” to Putin.

As, of course, do the applications of Sweden and Finland to join NATO, whether or not Turkey drops its objections to letting them in. It’s a signal Putin may consider to be rather hostile and unfriendly, but warning people you’re going to harm them if they try to defend themselves would seem to be fairly pointless and clearly a counter-productive exercise. We have to wonder if Putin really has a proper grip on reality and logic.

A BALANCING ACT

So, let’s look more closely at Mette Frederiksen, who was born on November 19th 1977 in Aalborg, making her Denmark’s youngest-ever prime minister. Her father, Flemming Frederiksen, was a typographer and her mother, Anette, was a teacher. She has a daughter, Ida Feline, and a son, Magne, and she also has a master’s degree in African Studies from the University of Copenhagen. She’s a member of the Social Democratic Party, which she has led since 2015. She spent a short spell working for a trade union but most of her life has been lived as a professional full-time politician. When she was elected, she became Denmark’s second female prime minister, having been a member of the Folketing since 2001. The political group she leads has a great many component parts: her Social Democrats, the Social Liberals, the Socialist People’s Party, the Red-Green Alliance, the Faroese Social Democratic Party, and Greenland’s Siumut and Inuit Ataqatigiit, all of them left of centre in some way, as well as her minority Social Democratic party, backed by the so-called Red Bloc.

She had partly campaigned on an anti-immigration platform but changed her position briefly to allow more much-needed foreign labour into the country. In a biography, she wrote that: “For me, it is becoming increasingly clear that the price of unregulated globalization, mass immigration, and the free movement of labour is paid for by the lower classes.” An internal poll carried out by her party found that 37% of the members (still a minority but a fairly large one) believed Denmark’s immigration policy was too weak and should be tightened. It seems that Frederiksen agrees, and it’s a view she shares with the right, despite moving further to the left on economic issues. She has called for a cap on “non-western immigrants” and for a law to ensure that immigrants work 37 hours a week in order to qualify for benefits. After some uncertainty, her party voted against plans to hold foreign criminals in an offshore facility used for research into contagious animal diseases and with no bridge to the mainland. In other ways, however, she has earned condemnation from the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR) for leading her party to join with the minority Liberal government of the time and to vote in favour of a law allowing her country’s authorities to confiscate money, jewellery, and other valuable items from refugees crossing the border into Denmark. They would have been allowed to retain just DKK 10,000 (€1,340), bringing them – arguably – into line with Danish citizens who must sell any assets they own worth more than that before they become entitled to social benefits. After the vote, Johanne Schmidt-Nielsen of the opposition Red-Green Alliance Party described it as “a symbolic move to scare people away from seeking asylum in Denmark.” That would appear to have been an astute observation.

In addition, the new law would, in many cases, triple to three years the waiting period for family reunion applications, shorten the duration of temporary residence permits, and tighten conditions for the issuance of permanent permits. The Prime Minister at the time, Lars Lokke Rasmussen of the centre-right Venstre party, shrugged off criticism of the proposals to seize assets, calling them: “the most misunderstood bill in Denmark’s history”. And arguably the most heavily criticised: “The decision to give Danish police the authority to search and confiscate valuables from asylum seekers sends damaging messages in our view,” UNHCR spokesperson Adrian Edwards told reporters, while Amnesty International regional director John Dalhuisen described the vote as “mean spirited”. The UNHCR later likened the idea to the treatment of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Frederiksen’s party also voted to ban the wearing of burqas and niqabs, which has drawn similar criticism. Denmark is not alone in seeking to restrict the wearing of religious face coverings; there are various but similar laws in place in Belgium, France, Germany and the Netherlands. In Denmark’s case, Muslim women who defy the ban risk a fine of DKK 1,000, (€130) rising to DKK 10,000 (€1,300) for repeat offences and even to 6 months in prison. Frederiksen argues that it liberates Muslim women and promotes gender equality, although it’s not clear if Muslim women see it that way (Muslim women I met in Afghanistan many years ago said they would feel less exposed running through the streets naked than removing their niqabs or burqas in public, so perhaps it is the mindset, rather than the choice of clothing, that needs to be addressed). The explanation is widely seen as an excuse, anyway.

Søren Espersen of the right-leaning Danish People’s Party supports the ban and dismisses what he sees as unnecessary vindications, along with: “all the contortions we have to make in order to avoid ‘discrimination’. This is about the burka and niqab and nothing else. Let us just discriminate. I do not give a damn.” The ban certainly has Frederiksen’s support, although as Justice Minister in 2014 she opposed the idea. Espersen’s remarks, however, are unlikely to win over other Social Democrats. Strangely, research by the University of Copenhagen in 2009 found that only around 0.1% – 0.2% of Muslim women in Denmark (that was around 200 individuals at the time) actually wear the niqab, while even fewer wear the burqa, and only around 5% of Denmark’s 5.7-million inhabitants are Muslim anyway. The Religious Freedom Institute wrote that: “Ironically, then, one could say that the first ‘problem’ with Denmark’s new burqa ban is finding a burqa to ban.” It would seem that Frederiksen, as Justice Minister back in 2014, when such a ban was first mooted, was right when she said that; “In my opinion, it is out of proportion to start legislating about it.” She obviously changed her mind. The official excuse adopted by Venstre and others is to overcome any terrorist threat resulting from people being able to hide their faces. The Religious Freedom Institute suspect that the real reason is so that Venstre can retain the support of the European People’s Party in order to remain in power, because: “Denmark is not suffering from a crime spree conducted by groups of burqa-clad Muslim women.”

UPSETTING TRUMP

Frederiksen proved herself strong (and certainly less controversial) by standing up to the then President of the United States, Donald Trump, when she refused to sell the autonomous region of Greenland to him. Not that it was hers to sell, of course. Trump had discussed with his aides the possible purchase of the territory, despite Kim Kielsen, the Premier of Greenland, clearly stating that it was not for sale. Frederickson described the whole idea as “absurd”, adding that: “Greenland is not Danish. Greenland belongs to Greenland.” In a fit of pique, it seems, Trump then cancelled a state visit scheduled for later that year, blaming the decision on Frederiksen’s refusal to talk about selling him Greenland. Caveat emptor, as the saying goes, assuming the caveat part proves possible.

Frederiksen has been highly critical of the EU’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which opinion she is far from alone, but it helped to cement her reputation as “Denmark’s most Eurosceptic Prime Minister”, which she has held for years. She has continued to criticise the EU vaccination programme and the EU’s general response to the crisis, all very understandable. Her attempt to get mink farmers to cull their animals (in case they were carrying the virus) proved to be less so and was ruled out as “unconstitutional”. It must have come as a relief to the mink themselves. In 2021, after talks with Chancellor Sebastian Kurz of Austria and Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu, she agreed a joint programme of research and development with them, together with plans to consider a shared production facility to provide long-term supplies for booster shots against the SARS-CoV-2 virus and to deal with any possible mutations. Denmark under Frederiksen became embroiled in the tension between the United States and Iran after the assassination of the Iranian general, Qasem Soleimani, by US forces. Frederiksen said it was “a really serious situation” and avoided answering questions about the killing. Having disappointed Trump, however, she was not anti-American and initiated talks earlier this year on the possible stationing of US troops on Danish soil, expressing enthusiasm for the idea. She is reported as saying: “We want a stronger American presence in Europe and Denmark.” It could be a good idea. It’s being reported that Putin is becoming ever-more paranoid after a recent attempt on his life, which has already deepened his isolation and could make him more inclined to resort to using nuclear weapons. He is said to believe that the West will “blink first” in the ongoing battle of wills.

Frederiksen wanted to be a ‘prime minister for children’, with plans to give local authorities greater powers to remove children from violent households, and to give children a greater say in divorce cases, but global events have slightly knocked her off track. Following Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, Frederiksen called together the country’s five main political parties to talk about the available options. The five are: her own, plus the Social Liberal Party, the Socialist People’s Party, Venstre and the Conservative People’s Party. Together, they came up with what they called the “National Compromise on Danish Security Policy”, with a steep increase in defence spending: an emergency allocation of DKK 7-billion for the defence of Denmark (that’s €940-million), a plan to end dependence on Russian gas and the referendum on that opt-out from EU defence policy, now clearly won by the side wanting to end the opt-out. Denmark will now move towards stepping up its spending on defence to 2% of GDP by 2033, in accordance with NATO’s preferred levels. It means that the spending on defence will increase year-on-year by DKK 18-billion €2.42-billion).

Frederiksen said in a speech: “When a freedom threat knocks on Europe’s door and there is once again a war on our continent, then we cannot remain neutral.” Her people seem to share that view. “We support Ukraine and the people of Ukraine,” she said. “Tonight, Denmark has sent a very important message. To our allies, to NATO, to Europe. And we have sent a clear message to Putin.” Denmark has also sent 700 soldiers to the Slagelse military base in Western Sjælland to reinforce the country’s defences while Danish jet fighters will be sent to the island of Bornholm. Russia advised Denmark against the move but Frederiksen responded by saying: “I can give a very short answer to this. The Russian ambassador should not get involved in what happens on Bornholm.” The Danish government wants to leave Putin in no doubt that Denmark will be defended.

Moscow has expelled Danish diplomats in the inevitable tit-for-tat response to Denmark’s expulsion of their Russian counterparts. Russia has also now turned off the gas to Denmark, too, because it refused to pay for it in roubles. The Danish energy conglomerate, Orsted, reassured customers that it will still be able source natural gas supplies from the European gas market after Gazprom announced that it would turn off the taps. Frederiksen had announced in March that she planned to end her country’s reliance on Russian gas and seek Denmark’s energy elsewhere. It’s that demand for payment in roubles that is the stumbling block, for Denmark and others. “This is totally not acceptable,” Frederiksen told a press conference. “This is a kind of blackmailing from Putin. We continue to support Ukraine, and we distance ourselves from the crimes that Putin and Russia commit.” Russian state gas giant Gazprom has confirmed that it had stopped gas supplies to Denmark’s Ørsted as well as to Shell Energy Europe after the two companies refused to abide by the rule on payments in roubles. The head of the Danish Energy Agency, Kristoffer Böttzauw, told the media: “We still have gas in Denmark, and consumers can still have gas delivered.” And if the situation should worsen, he told journalists that he has plans in readiness.

In fact, Denmark has been a net exporter of natural gas for many years, but its Tyra field in the North Sea is being renovated, which means that the country currently has to import about 75% of its gas through Germany. The Tyra field should be able to be reopened in the middle of next year. In Denmark, some 380,000 households use natural gas for heating.

WHY, WHEREFORE AND WOEFUL

The reason the referendum on the defence opt-out was needed stems from the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, when Danish voters demanded four “special arrangements”. The signing ceremony was a very grand affair and those of us who were there knew we were witnessing something that was historically important. Denmark opted out of sharing policies with the other EU member states in several areas: defence policy (the opt-out they have now voted to abandon), the single currency (the euro), justice and home affairs, and also insisted that EU citizenship could only ever complement Danish citizenship, never replace it, a position that became the case for all member states under the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997. Denmark has also held referenda on joining the euro, in which the people rejected the idea, despite political parties and trades unions supporting it. The Danes also voted to retain their country’s opt-out on justice and home affairs, against the advice of their government. That has enabled Denmark to follow Britain in doing a deal with the East African country of Rwanda to take its unwanted migrants, even though the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi, has condemned the scheme as an “egregious breach of international law” and “contrary to the letter and spirit of the Refugee Convention”.

Such criticism hasn’t had any effect on the United Kingdom, where Prime Minster Boris Johnson and his Foreign Secretary, Priti Patel, have agreed to pay the Rwandan government £120-million (€140-million) to accept Britain’s “rejects”, which leaves many in the UK feeling vaguely ashamed. It looks like buying a solution (or trying to) that is no solution at all, or certainly not for those in desperate need of help.

Putin seems to be achieving the exact reverse of what he wanted at the outset of his war: he wanted Ukraine to become a part of Russia, despite he himself being hated by most Ukrainians (Kyiv’s street markets have been selling rolls of lavatory paper with pictures of his face on the sheets for years), he despises the EU but has helped to make it more unified that it was.

He wanted to warn NATO to stay clear of Russia’s borders but has attracted other neighbouring countries to seek membership, expanding NATO’s footprint. Now non-military Denmark has joined the EU’s Common Defence Policy but it had already announced its readiness to help with arming Ukraine.

“I am ready to send military equipment to Ukraine,” Frederiksen told a press conference. “We are already giving advice.” Denmark has been helping Ukraine with cyber security since January following a cyber attack that Kyiv blamed on Moscow. The EU has also agreed to ban some 66% of Russia’s oil imports, which will hit Moscow’s revenue stream quite substantially. Most EU leaders had been hoping for a larger-scale ban, but Hungary refused to cooperate, citing the country’s reliance on Russian energy. The real reason, however, may lie in the close relationship between two anti-liberal leaders: Viktor Orbán and Vladimir Putin. They are friends who think alike on a lot of issues. Orbán even broke the isolation imposed on Putin following his annexation of Crimea, which did not please his EU partners. He accuses them of depicting Putin as having “hooves and horns” when he rules what is (according to Orbán) “a great and ancient empire”. Orbán also copied Putin’s techniques for despotic rule, taking over all media outlets to ensure all news reports about him are positive, and also gathering around himself wealthy oligarchs who view power as little more than a route to greater wealth. Then, in 2014, Orbán’s government awarded a €12.5-million contract to renovate Hungary’s only nuclear power station, Paks, to the Russian state-owned corporation, Rosatom.

In fact, thanks to Orbán, Hungary is very much in hock to Moscow, even though more than 80% of its own exports go to its EU neighbours. Russia supplies 57% of its natural gas and 89% of its oil, and Orbán has upheld Russia – under Putin – as a positive example of an “illiberal democracy”. Orbán sees the notion of illiberal democracy as the way forward, presumably because it means he’ll be free to run his country as he chooses without any checks or balances and without reference to anyone else, like a mediæval monarch. Orbán thinks we should get used to them because they’re growing in number and thinks they’re the future for Europe. Fareed Zakaria, Managing Editor of ‘Foreign Affairs’, defines illiberal democracies as “democratically elected regimes often re-elected or reinforced by referendums that ignore the constitutional limits of their power and deprive their citizens of basic rights and liberties.” He fears they’re on the increase, citing the examples not only of Hungary but also of Poland, Slovakia and Croatia, not to mention Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Some have included Donald Trump as a leader who would favour an ‘illiberal democracy’ if he could achieve one.

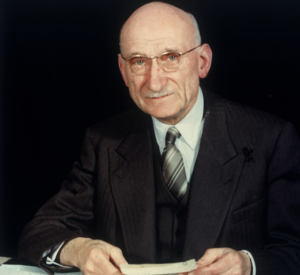

Certainly, Budapest’s goals are not those of the EU’s founders. Hungary’s alternative vision of illiberal democracy comprises order, press control, the importance of family, observance of religion, the cult of the homeland, a ‘mythification’ of the past (in other words, telling lies about it so it seems more glorious than it was), and even the re-establishment of the death penalty, which Orbán considered putting on the agenda in May 2015. It’s a million miles away from the statement by Robert Schuman, the French Foreign Minister, first spoken in the Salon de l’Horloge at the Quai d’Orsay in Paris.

He was the co-founder of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) that would one day evolve into the EU, believing that if control over coal and steel – what he called “the engines of war” – were put under common control there could never be another war. That was back in the days of politicians with vision, who seem to be in rather short supply these days. Schuman was speaking not long after the Second World War, shortly after adopting the plan for Europe dreamed up by the ECSC’s co-founder, Jean Monnet, the French entrepreneur, diplomat, financier, administrator, and political visionary. “World peace cannot be safeguarded without the making of creative efforts proportionate to the dangers which threaten it,” Schuman said. “The contribution which an organized and living Europe can bring to civilization is indispensable to the maintenance of peaceful relations.” Note: we’re talking about “civilisation” here, not a “devil-take-the-hindmost” dash for power for its own sake, which seems to be the aim of illiberal democracy’s proponents. Therein lies the difference between illiberal democracy and Schuman’s dreams of building a lasting peace.

ILLIBERALISM ON THE RISE

The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) has warned of growing tension between EU standards, along with the Union’s way of ruling, with the beliefs of those who want illiberal democracy. “The Europe of rules, principles, and procedures is clashing head-on with the political Europe of strongmen who use raw power and codes of honour. It is a dirty but fundamental fight,” it said. It’s worth noting, too, that what these strongmen call “honour” is, in reality, a secession, a total abdication to the strongmen’s will. It would be the end of compassion, debate, and consideration for others. Nobody discusses policy; the strongman (or woman) simply imposes his (or hers).

Orbán sees himself as offering a ‘Christian’ way of governing (so does Putin, theoretically), although you may not recognise it as that and nor may most Christians, I would guess. Basically, it comes down to rule by bullying. That is something Mette Frederiksen does not want to see. During a recent visit by the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, Frederiksen urged him to try to stop the war in Ukraine by putting pressure on Putin. It’s unlikely to have much effect; India chose to remain neutral, earning plaudits from Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, who praised India for judging “the situation in its entirety, not just in a one-sided way.” Frederiksen blames Europe in part for not getting close enough to India. “In fact, it is quite obvious that we in the West,” she told journalists, “have a completely unequivocal interest in getting India as close to us as at all possible.”

Meanwhile, Russia continues its unjustified attack on Ukraine. It has attacked a railway in the west of the country, using cruise missiles. CNN reports that the strikes occurred close to the Beskyd tunnel in the Carpathian mountains, not far from the border with Slovakia. It’s the second time that Russian forces have targeted the line. According to the report, the goal was to: “disrupt rail traffic and stop the supply of fuel and weapons from our allies.” Frederiksen, meeting in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, with its Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė, agreed that more sanctions are needed against Russia and against Belarus. We tend to forget Belarus and its rôle in Putin’s war, but it carries on, like a small but vicious dog biting the enemies of its owner’s best friend. Belarus recently redirected a Ryan Air flight to Minsk, seized Russian student Sofia Sapega and her journalist boyfriend and has now sentenced her to six years in prison for stirring up dissent. That’s the sort of thing that an illiberal democracy can lead to. Forget justice; the convenience of the leader is all that matters.

You will recall that I started with the mathematical formulae for entropy and the inevitability of disorder. Putin and his odd supporters, including Orbán, should perhaps recall that there is also an inevitability about decay. It’s not only disorder that is unavoidable, it’s everything. Exponential decay can measure the way that amounts (and power, presumably) decline by a series of set percentages in accordance with a well-known mathematical formula: y = a (1 – r)x. In this equation, a is the initial amount of something, r represents the decay factor and x is the time interval. Given the recent attack on Putin at home, his time may be shorter than he hopes. Even Orbán, despite his recent election victory (his opponents and critics say the result was fraudulent, but that’s an acceptable route to power in an illiberal democracy) may not be unassailable. It all comes down to maths at the end, and the question of how long a leader will stay in power, with an answer somewhere between 0 (zero) and a higher number, but not even the most deranged and optimistic politician will ever reach infinity (∞).