© Edm

Russia’s President, Vladimir Putin, is not famed for his diplomatic language. Even so, his threat to “knock the teeth out” of any nations laying claim to what he considers Russian territory is somewhat extreme. Anyway, how could you knock out an entire nation’s teeth? Russia is a vast country, of course, and as it borders the north polar region, it’s understandable that it seems determined to claim more of the seafloor as part of its continental shelf. Planting a Russian flag on the sea bottom at the actual pole, which it did in 2007, is going a little bit too far, say some of Russia’s neighbours. For example, Canada’s Foreign Minister at the time, Peter MacKay said “This isn’t the 15th century. You can’t go around the world and just plant flags saying ‘we’re claiming this territory’.”

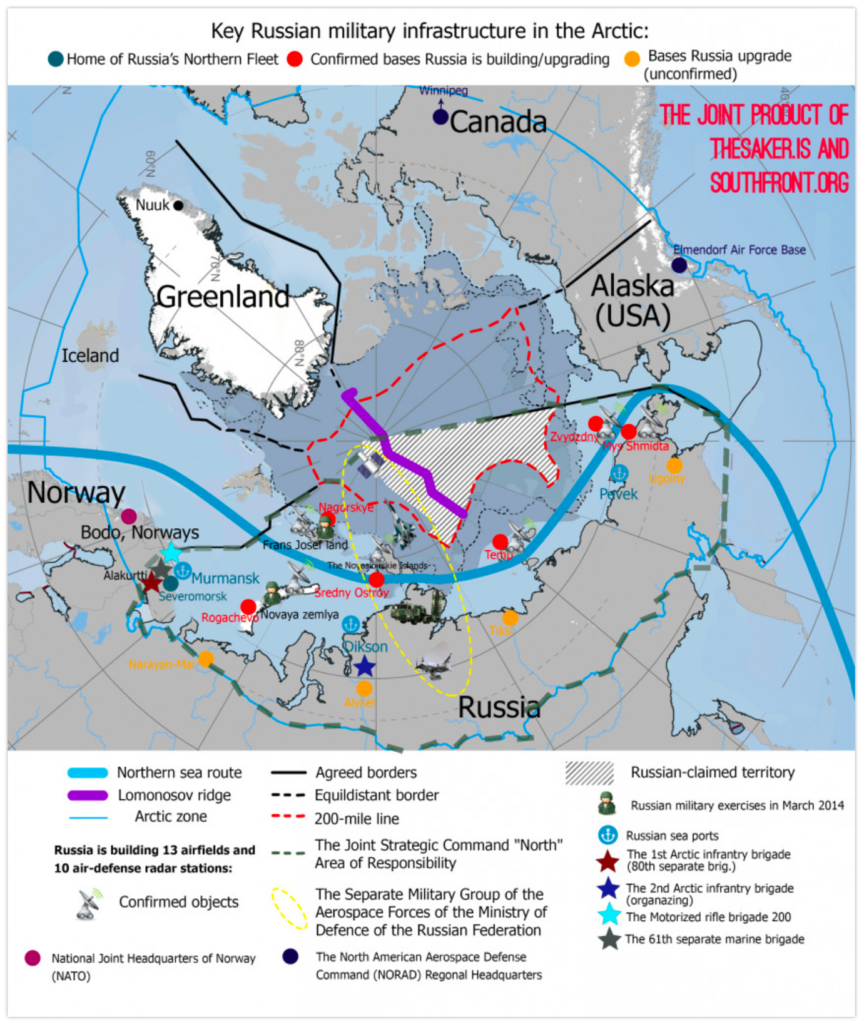

Although the longest stretch of coast by far in the Arctic Circle is Russia’s, parts of Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Norway also have a claim. It may be one of the coldest places on our world but tempers about it are getting hotter. Russia has warned the West against militarising the polar region but has also shown off its own massive new military airbase at Nagurskoye, on the Franz Josef Land archipelago, the most northerly part of Russia’s Arkhangelsk oblast.

The reasons for all this sabre rattling are money and personal prestige. As the ice retreats because of global warming, it is opening up access to vast reserves of oil and gas as well as rare earth metals. Hence Putin’s bombastic threat of physical violence. While Russia clearly has a strong claim to territory near the North Pole, its claim to the other end of the world is less obvious.

Russia maintains that as the land of Antarctica was first sighted by a Russian expedition in 1820, since when Russian mariners and researchers have played a leading rôle in exploring the place, it should be seen as Russian. Putin-loving Russian TV presenter Dmitry Kiselyov even stated one evening that “Antarctica is ours”. If Russia’s claim is based on having seen the place in 1820, the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge could have made a similar claim. It was in 1798, after all, that his brilliant (and very long) poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was published in the first edition of his Lyrical Ballads. He didn’t name Antarctica in the poem, but it seems fairly clear that it’s the place the poor old Ancient Mariner’s ship had been blown to by a fierce storm:

“The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!”

Coleridge described it in his odd ‘side notes’ as “The land of ice, and fearful sounds, where no living thing was to be seen.” There were no penguins there either, it seems, although Coleridge may not have known about them. It’s there, however, that the Ancient Mariner and the rest of the crew come across a very large seabird:

“At length did cross an albatross,

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God’s name.”

Anyway, it proves to be ‘a bird of good omen’ because the imprisoning ice cracks and “The helmsman steered us through”. It was probably a wandering albatross, which inhabits Antarctica and has the largest wingspan of any bird at 3.5 metres. But size isn’t everything, of course: the albatross is notable for other things, too, like never flapping those enormous wings in flight. It glides instead and is at risk of extinction as it mates for life with a single partner and together they only produce one egg every two years. Their fishing trips can last for up to twenty days, during which they may cover some 10,000 kilometres. Of course, if the crew had disembarked and looked around a bit more they might have met penguins, too, or elephant seals, while a glance over the ship’s rail could have given them sight of a humpback whale or an orca, but they seem not to have entered into Coleridge’s (probably opium-induced) dream. It seems he wrote some of his most imaginative poems while stoned out of his mind on opium to cope with the pain he suffered from systemic lupus erythematosus, SLE. His Ancient Mariner had a terrible time even after escaping from this unnamed icy land, getting marooned later in what was probably the Sargasso Sea, (although Coleridge doesn’t name that, either) while the figures of Death and Life-in-Death play a game of dice for the souls of the crew. Life-in-Death wins the eponymous sailor, compelling him for ever after to go around frightening wedding guests with his ghastly tale. Even so, he never said “Antarctica is ours”. He just wanted people to be nice to albatrosses and all other creatures, which may not be a matter of much concern inside the Kremlin. In any case, under the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, the place is officially neutral. No country can lay claim to it, and it can only be used for peaceful and scientific purposes.

As far as that is concerned, Russia has ten research stations in Antarctica but only half of them are operational all year round and most of them are in a fairly dilapidated state and desperately under-funded. Other research bases there belong to Chile, Finland, the United States, Poland, New Zealand, Uruguay, Japan, Australia, Argentina, India, South Africa, Chile, Brazil, Germany, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, the UK, Spain, Italy, South Korea, Pakistan, Belgium, China, Romania, Peru, Ecuador, Bulgaria, Sweden, New Zealand, Ukraine and Italy. If I have missed any countries off the list I apologise. Some of those research facilities are permanent, some are only used during what passes for summer in Antarctica. The English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote his seventh symphony about the place, Sinfonia Antarctica, based on the film music he had written in 1947-48 for the film, Scott of the Antarctic, about Captain Robert Scott’s ill-fated trip to the South Pole in 1912 (they arrived only to find they had been beaten to it by a Norwegian party led by Roald Amundsen). Scott and many others died during the return from the Pole in what turned out to be the worst weather seen there for years, but the music is wonderful. Vaughan Williams, being both a confirmed Socialist and a pacifist would never have claimed ownership of the place as Kiselyov did.

NORTH AND SOUTH

But let us return to the other end of the world, the Arctic and the North Pole, over which Russia at least has some sort of legitimate claim. The Arctic can boast some 4-million inhabitants, of whom 2-million are Russian. It’s there that Russia wants to maximise its access to the rich natural resources. Russia says it’s equally keen to protect the ecosystems of the Arctic, as well as ensuring that the shipping routes through it remain open. It also says it wants the area to remain “a zone of peace and cooperation”. In order to ensure it remains peaceful (the Kremlin says) it maintains a large military presence there, which it plans to expand considerably. Since it clearly hasn’t been built to fight aliens from outer space, it seems it must be intended to menace the West. Russia also plans to enhance the presence of its border guards there.

Of the sea routes it wants to maintain, the Northern Sea Route, which lies to the east of Zemlya and runs along Russia’s Arctic coast from the Kara Sea, along Siberia to the Bering Strait. It is the most important sea route for transportation and it’s said that Russia’s Security Council is looking at ways to develop it, partly by investing in improving the infrastructure. Some would argue that its research stations are really there to back up Russia’s territorial claims on the seabed of its continental shelf. Its stated desire to create a ‘zone of peace and cooperation’, however, is hard to square with its Nagurskoye military airbase in the Franz Josef Land archipelago. Neither does it really fit with the fiercely-spoken words of Russia’s combative foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, that he could see no reason for any military programmes in the area by other countries. It was said at a prickly Arctic Council meeting in Reykjavik, Iceland in May, where Putin made his “knock their teeth out” comment.

What both men would seem to be saying is that Russia must be allowed to militarise the region as much as it likes but woe betide any other country bordering the Pole that does anything similar, on however small a scale. “We have highlighted at the meeting,” Lavrov told a press conference, “that we see no grounds for conflict here. Even more so for any development of military programmes of some blocs here.” Perhaps Putin and Lavrov are merely adopting the policies of Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus, a Roman writer known only for this one military work, De Re Militari (Regarding Military Matters) written in the 4th century CE (probably), and another on veterinary medicine. The quote most often heard is: “Igitur qui desiderat pacem, praeparet bellum”, which is normally rendered as simply “Let he who desires peace, prepare for war”. It made sense in classical times and it worked after a fashion during the Cold War: two rival blocs, each armed to the teeth with nuclear weapons, facing each other across a global stage. The war occasional got warm but never completely hot, despite some scares. I was at my local grammar school when the Cuban Missile Crisis erupted; it was the talk of the school yard as my friends and I wondered when we’d be called up for military service.

OUR GUNS ARE BIGGER THAN YOUR GUNS

Russia’s attitude at the Arctic Council did not sit well with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken who said it was important that all countries and parties “uphold effective governance and the rule of law” to make sure that the “Arctic remains a region free of conflict where countries act responsibly”. That would seem to be an idle hope. Clearly, that lack of grounds for developing military programmes doesn’t apply to Russia. Whilst stressing the importance of Russia’s own ambitious military developments, Lavrov said he would ‘speak to’ Norway’s Foreign Minister, Ine Marie Eriksen Soreide about the reinforcement of her country’s military presence near to the Russian border. In Moscow’s view, only Russia should be allowed to build facilities and rattle its sabres. Lavrov warned Blinken against deploying any additional US forces in Poland, too, pointing out that to do so would be in violation of the 1997 treaty on relations between Russia and NATO.

However, work continues on developing the Nagurskoye airbase, with its runways being extended to 3,500 metres, so that they can handle every kind of aircraft, including the 4-engined Ilyushin Il-76 airlifter, which can carry 126 paratroopers with parachutes, 145 personnel in a single-deck version and 225 in a double-deck version, and heavy strategic bombers like the Tu-95 Bear, a four-engine turboprop-powered strategic bomber and missile platform, as well as strategic jet fighters, of course. The Russian military invited various media organisations on a rare tour of the facility earlier this year, where they were told that apart from its capacity to refuel and work with Russia’s heaviest aircraft, it has been constructed to house 150 soldiers with the main aim of maintaining the viability of its Northern Fleet. Putin has stated that it’s all part of a plan to bolster Russian presence within the Arctic Circle to “ensure the future of Russia”. Since the vast facility is only 257 kilometres from the coast of Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, it clearly looks more like a threat to Western interests. The displaying of its remarkable facilities to Western journalists looks suspiciously like a playground game from my junior school that involved the outside and roofless toilet block and a degree of bravado. It was a game that the owners of houses whose gardens backed on to the wall didn’t much like. The cane awaited any boys caught in the act.

Russia showed journalists what it described as a “state of the art” radar facility, with which they claimed to track the movements of NATO ships and aircraft, even boasting that they have frequently monitored American and other aircraft it considered “adversarial”. The Russian also showed off its Bastion coastal defence missile system which, it claims, can strike at maritime or land targets more than 320 kilometres offshore. US Secretary of State Blinken has previously expressed “concerns about some of the increased military activities in the Arctic.” It’s not as if Putin makes any secret of Russia’s aggressive stance. Returning to his “teeth” analogy, what he actually said was that his country boasts huge energy reserves and he would react strongly if anyone sought to “bite off” a part of them. “They should know, those who are going to do this, that we will knock out everyone’s teeth so that they cannot bite anymore.” He also added that the key to this teeth-bashing exercise is “the development of our armed forces.” Every country has the right to defend its territory, of course, but Putin seems to see national territory as a moveable feast. Russia’s seizure of Crimea provides an object lesson.

The nerve centre of Russia’s Arctic ambitions is the closed town of Severomorsk, in the oblast of Murmansk, on the coast of the Barents Sea and 25 kilometres from the city of Murmansk itself.

It’s the headquarters of Russia’s Northern Fleet and it is home to some 50,000 people. Under the United Nations Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), coastal nations with territory inside the Arctic Circle itself are entitled to exploit them within 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) of their coastal baselines. If those countries subsequently want to claim undersea territory as part of their continental shelf, they have to submit geological evidence to the UN.

Moscow must deeply regret the disappearance of Beringia, the land bridge that used to exist between Siberia and Alaska. Today, it’s defined in Wikipedia as “the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula”. It was not a safe place for paleolithic man to go, with large predators such as giant short-faced bears, Beringian cave lions, scimitar-toothed cats, mammoths, and grey wolves. During the Late Glacial Maximum (LGM) of 31,000 to 16,000 years ago, it was also quite cold. Dangerous it may have been, but it seems to have brought the ancestors of today’s native Americans all the way from North Siberia. They merged with another group, the Ancient East Asians some 25,000 years ago and in so doing provided the majority of the DNA now found in most of what Americans call the “First People” by which they mean the first to reach and settle in what would become the United States.

They then split into two groups between 18,000 and 22,000 years ago, according to an article by Jennifer Raff, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Kansas, in the May 2021 edition of Scientific American. One of these groups, the Ancient Beringians, seems to have died out without leaving any descendants, although they left traces in Alaska.

“The other branch, known as the Ancestral North Americans,” Raff writes, “gave rise to the First Peoples south of the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.” The land of Beringia is often thought of as having been a bridge between Asia and North America, but according to Hakai magazine, that is a misleading picture.

“The ‘Bering land bridge’ wasn’t a bridge at all, for instance—at its greatest extent, it was a landmass roughly as large as Australia, stretching 1,600 kilometers north to south and 4,800 kilometers east to west, from Canada’s Mackenzie River to Russia’s Verkhoyansk Mountains. Scientists call it Beringia.”

SNOW FLOWERS?

Nor was it just a frozen wilderness, says an article on line. According to fossil and pollen evidence, it supported wildflowers and shrubs, which provided food for such creatures as the steppe bison, western camels, pleistocene horses (there were several species, which were mainly smaller than their modern descendants at only some 5 hands high) , antelope and woolly rhinoceros. Despite the ice on every side, Beringia itself stayed largely ice-free, more like Alaska is today, according to Hakai magazine. The LGM locked up vast volumes of water in ice and caused sea levels to fall by around 100 metres, according to the US National Park Service. “For perhaps 80% of the last million years, Alaska has been joined to Siberia by this land bridge,” says its website. It goes on to suggest that it had other effects, too. “The land bridge did more than link the two continents,” says the website. “It also ushered in a new climatic regime to the entire Beringian region by blocking Pacific moisture from entering the interior regions of both Alaska and north-eastern Siberia. Thus these regions became much drier than they are today. In fact they became so dry that their lowlands remained ice-free, even during the coldest climatic episodes of the ice ages.”

So, what happened to Beringia? Let’s start with where it used to be. This is the explanation given on the website of the US National Park Service: “Beringia is the land and maritime area between the Lena River in Russia and the Mackenzie River in Canada and marked on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chuckchi Sea and on the south on the tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula.”

The website goes on to point out that some small parts of Beringia would seem to survive out of the water: “As the ice age ended and the earth began to warm, glaciers melted and sea level rose. Beringia became submerged, but not all the way. The Diomede Islands, the Pribilof Islands of St. Paul and St George, and St. Lawrence and King Island still poke out of the water.” So far, the Kremlin hasn’t claimed them, but its militarisation of the Arctic is certainly worrying Western nations.

According to CNN: “Russia is amassing unprecedented military might in the Arctic and testing its newest weapons in a region freshly ice-free due to the climate emergency, in a bid to secure its northern coast and open up a key shipping route from Asia to Europe.” Weapons experts in the West are particularly worried about Russia’s new Poseidon 2M39 torpedo. According to Popular Mechanics magazine, this is more than simply a torpedo. “Russia’s intimidating nuclear-powered torpedo is running toward new key tests this year,” says the magazine, “with a planned deployment for later this decade. The ‘tsunami apocalypse torpedo,’ the first of its kind, is designed to travel across the world’s oceans to deliver a knockout thermonuclear blow against a coastal target or city.” The missile seems especially important to Putin, who has asked his defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, for updates on the results of the tests it must undergo. The progress is also being closely followed in state media and it sounds like a very unpleasant weapon indeed. A leaked (deliberately) Russian Ministry of Defence document told the world what it could achieve: “The defeat of the important economic facilities of the enemy in the vicinity of the coast and causing assured unacceptable damage to the country through the establishment of zones of extensive radioactive contamination, unsuitable for implementation in these areas of military, economic, business or other activity for a long time.”

Ironically (and perhaps tragically) the path of this missile, if it’s ever launched, may trace the route taken by the settlers whose descendants would become the first Native Americans. Of course, the other result of firing it would be all-out nuclear war, an atmosphere completely contaminated with radiation for thousands of years and the destruction of humankind. Further leaks, printed in Popular Mechanics, describe it as a nuclear-powered giant torpedo, or even a large crewless submarine, measuring 6.5 feet (2 metres) in width and 65 feet (20 metres) long. The weapon can travel at speed of up to 70 knots, which is very fast under (or more likely on) water. With nuclear power, the weapon has a considerable range, and experts believe the Poseidon can travel across the Pacific and Atlantic oceans on its own to deliver its payload. The torpedo’s high speed will make it difficult for U.S. (or any other) forces to intercept. Some US defence experts believe that facilitating a visit to the Nagurskoye military base may have been intended as a mere show of force just before the meeting of the Arctic Council, of which Russia has taken over the rotating chairmanship. As a matter of convention, ‘the Arctic’ either refers to the five Arctic coastal states, including Canada, Denmark (because of Greenland and the Faeroe Islands), Norway, Russia, and the United States or the eight full member states of the Arctic Council (the five just listed, plus Finland, Iceland, and Sweden).

“Until recently,” writes Carnegie Europe on its website, “it made physical sense to distinguish between the ice-free areas of the North Atlantic Ocean and the Norwegian coastline, on the one hand, and the more or less permanently frozen areas within the Arctic Circle, on the other. So far, these two geographic areas have also corresponded to two different kinds of politics: regular security politics, including through NATO, in the Atlantic; and tentatively more cooperative international politics among the coastal Arctic states. Yet as polar ice melts and contracts, the Arctic, too, risks becoming a zone of increased great-power competition.” And, of course, as the Polar region melts, interests in the wealth being uncovered by the retreating ice have been growing.

“While NATO member states and Russia have significantly reduced the size of their navies,” says Carnegie Europe, “Russian development of new missiles in effect makes distances smaller and regions closer to each other. The range, speed, and precision of these weapons make it more difficult to separate the North Atlantic and the Arctic as distinct theatres of operations, as both the Baltics and the Norwegian Sea can be the targets of attacks from the Barents Sea as well as from land.

Land, submarine, and air-launched cruise missiles challenge NATO’s ability to reinforce both mainland Europe and the North Atlantic.” Russian concern to defend what it sees as its obvious interests around the North Polar region is understandable. Its interest in the South Polar region somewhat less so (unless it views penguins and krill as important likely food sources).

PICKING UP A PENGUIN

In recent years, Putin has sought to stress Russia’s interest in the Antarctic, complaining in 2018 that the various geographical names of places there have been better known internationally in their Western forms. He grumbled that names given by Russian explorers have been squeezed out, thus diminishing the awareness of Russia’s contribution to exploring the world and to world science. He even requested the creation of a new world atlas to show the Russian names for the world’s countries and cities, including places in the Antarctic. It has yet to surface, however. Meanwhile, Russia’s research stations in Antarctica are falling increasingly into disrepair and there is little sign of any additional funding being made available. When Russia sent a scientific expedition to assess Antarctica’s fish stock in 2019, it was the first for 15 years. Environmentalists would be very unhappy to see a Russian krill fishing fleet back in Antarctic waters, given that krill is a vital food source for whales and penguins. There have been attempts to create ‘no-fishing’ zones to the east of Antarctica but Russia and China have always blocked them, as they did a proposal for the world’s largest sanctuary in Antarctica, to protect penguins, reefs, various seabirds and the entire ecosystem. The two sides are unlikely ever to see eye to eye (or to meet flipper to flipper).

The Polar advisor to Greenpeace, Laura Meller, says Russia is “pursuing niche fishing interests whilst preventing the Antarctic Ocean Commission from fulfilling its mandate to create a network of sanctuaries in the Antarctic Ocean.”

Russia, meanwhile, accuses the Commission of adopting ‘discriminatory decisions’ by seeking to restrict its access to the resources of the Antarctic waters.

However, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) can claim some successes in its attempts to ensure that life continues in this most inauspicious part of the world, with inspections of fishing boats and the requirement that all vessels active there have a CCAMLR permit or licence. Inspectors can order vessels to stop while formal checks are made, and “If, as a result of inspection activities carried out in accordance with these provisions, there is evidence of violation of measures adopted under the Convention, the Flag State shall take steps to prosecute and, if necessary, impose sanctions.”

Greenpeace has been very critical of the CCAMLR for failing to get a more comprehensive deal. Frida Bengtsson, of Greenpeace’s Protect the Antarctic campaign, spoke of her disappointment with the outcome of the 2018 meeting in Hobart, Tasmania: “This was an historic opportunity to create the largest protected area on Earth in the Antarctic: safeguarding wildlife, tackling climate change and improving the health of our global oceans. Twenty-two delegations came here to negotiate in good faith but, instead, serious scientific proposals for urgent marine protection were derailed by interventions which barely engaged with the science.” Bengtsson was especially critical of Russia and China: “Rather than put forward reasoned opposition on scientific grounds, some delegations, like China and Russia, instead deployed delaying tactics such as wrecking amendments and filibustering, which meant there was barely any time left for real discussion about protecting Antarctic waters.”

But Russia does conduct scientific experiments in Antarctica. It was the Russian scientist Peter Kropotkin who first suggested in the late 19th century that fresh unfrozen water may be found under the Antarctic ice. It was then another Russian scientist, Andrey Kapitsa, who used seismic soundings made between 1959 and 1964 in the area of Russia’s Vostok Station to suggest the existence of a lake beneath the ice, and a Russian glaciologist, I. A. Zotikov, wrote his PhD thesis on the subject in 1967. Various Russian teams were involved in further research before one of them finally reached the lake itself, now named Lake Vostok, (such a Russian name must surely please Putin?) in 2012. The water in the lake had been sealed off from the atmosphere by some 4 kilometres of ice for 15-million years and it may even contain some life forms. Other scientists had helped along the way with advice, satellite scans and other such things, proving that scientists can cooperate without waving their flags while politicians seem to find that difficult. Of course, scientists deal only with facts; politicians, it seems, deal mainly with self-interest and image. It’s a cheering thought that the world of scientists usually outlasts the machinations of mere politicians.

Everyone remembers Galileo Galilei, few recall Pope Urban VIII or the member of the inquisition who “questioned” Galileo, Father Vincenzo Maculani da Firenzuola. Just as well, really; they’re irrelevant.