The new ICBM missile to replace the Soviet-era Voevoda © mil.ru

There’s no doubt, according to expert observers, that Russia’s current military capacity is far ahead of what it was just a decade ago. Given its rapid advances, many are beginning to wonder where it will be in another ten years. It is certainly raising eyebrows (and hackles) at NATO. In a speech in Hamburg in February, NATO Deputy Secretary General Mircea Geoană warned guests at the Matthiae Mahl dinner of the dangers he foresees. “For many years, we have seen a disturbing pattern of Russian behaviour. Its illegal annexation of Crimea and destabilization of Eastern Ukraine. A massive military build-up. The use of a military-grade nerve agent on Allied soil (the attempted murders of former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury, England). Cyber-attacks. Disinformation campaigns. Attempts to interfere in our elections. And the deployment of new, nuclear-capable missiles which can reach cities all over Europe.”

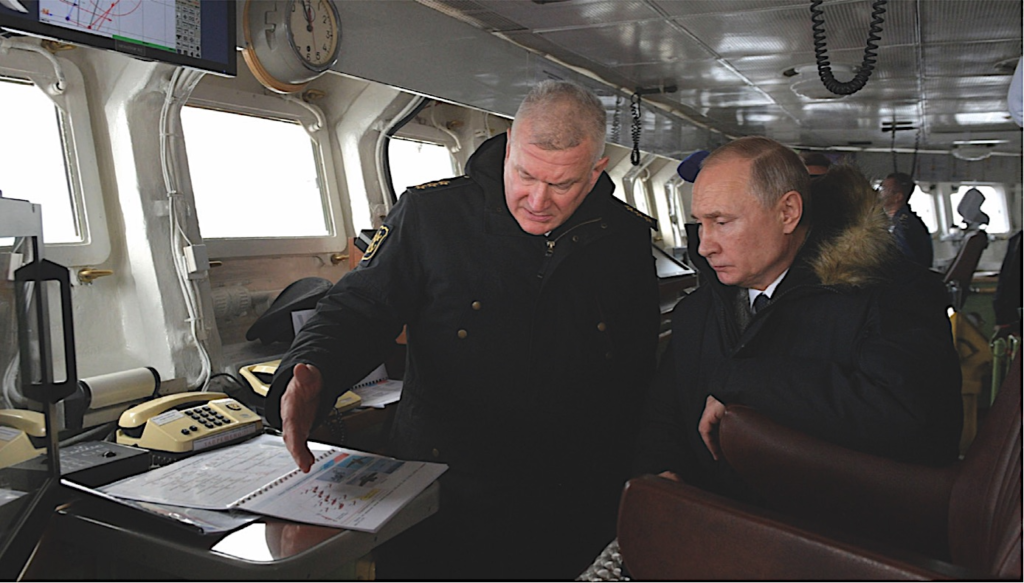

According to the Russians, not just Europe either. In December, President Vladimir Putin boasted that “Russia has got a strong edge in designing new weapons” and that it has become the only country in the world to deploy hypersonic weapons. He went on to tell military chiefs that “for the first time in history, Russia is now leading the world in developing an entire new class of weapons unlike in the past when it was catching up with the United States”. Mind you, the United States would argue that despite Putin’s claims, Russia is not the only country to deploy hypersonic weapons, even if Canada’s CBC News says that Russia’s missile would be “unstoppable”. As one American expert put it, unstoppable now doesn’t necessarily mean unstoppable tomorrow. And what’s more, although the missiles themselves may not show up on radar, research by the China Aerodynamics Research and Development Centre suggests that the plume of ionized gas, or plasma, left by a hypersonic vehicle is more visible on radar than the vehicle itself, which implies that radar could give early warning of an incoming weapon.

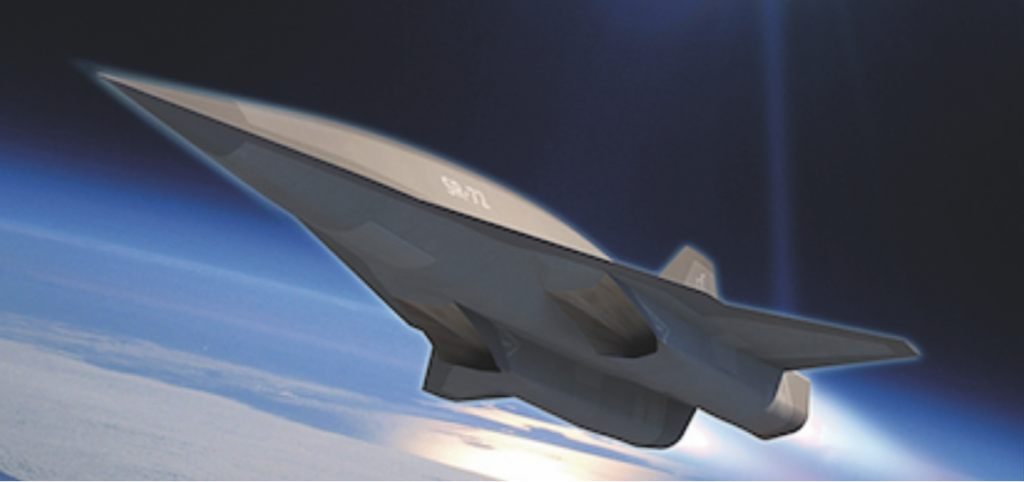

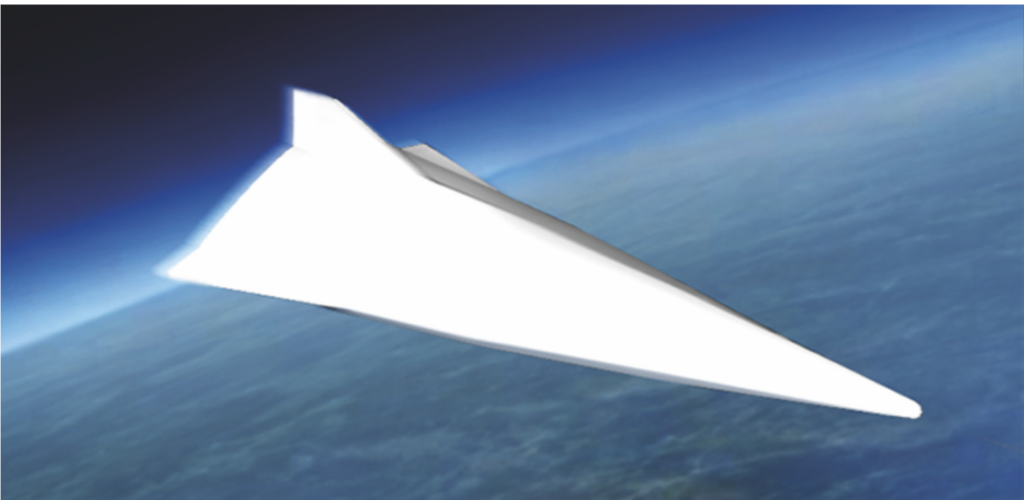

So, what exactly are hypersonic weapons and should they worry us? They’re missiles that travel at or above Mach 5 – five times the speed of sound. Since very few things can achieve such speeds, once they’re in the air they would be fiendishly hard to catch, even by very fast anti-missile missiles or the latest fighter jets. But hypersonic flight carries problems of its own, because of the heat generated. In 1967, an American X-15 research plane reached a speed of Mach 6.7, but on landing it was found that the pylon holding the engine to the body had melted. Putin announced that the Avangard rocket was ready in March 2018, and made no secret of the fact that it had been designed to neutralise American missile defences ahead of a hypothetical nuclear attack. The Avangard can travel at Mach 27. Normal propulsion systems won’t work at hypersonic speeds so the Avangard is powered by what’s called a ‘boost glide’ system, which accelerates the rocket to very high speeds within Earth’s atmosphere using what’s called a ‘scramjet’ (supersonic combustion ramjet) engine, then allows it to glide to its destination. Traditional Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) lift their payloads into low-Earth orbit – Russia uses its UR-100NUTTH missile, known to NATO as the SS-19 Stiletto – then send them down to pre-designated targets. Avangard uses its ISBM booster to lift it no higher than 62 miles (around 100 kilometres), just a third of a normal low-Earth orbit, from where it hits its target at Mach 27, which is 20,716 miles per hour, or if you prefer, 33,340 kilometres per hour. But the vehicles do get extremely hot from air friction, making their electronic guidance systems vulnerable, while turbulence creates additional problems, even if the vehicle is designed to withstand temperatures of 2000°C. At hypersonic speeds, the boundary layer around the vehicle thickens, and a smooth, laminar flow can suddenly break up into eddies and swirls that cause temperature spikes on the vehicle’s skin.

The Avangard is also capable of supple evasive manoeuvres in flight, making it even harder to intercept. Additionally, Russia has an air-launched hypersonic missile in service, the Kinzhal, which is carried on MiG-31 fighters. It’s not as fast as the Avangard but as it’s capable of reaching speeds of Mach 10, with a range of 1,240 miles (2,000 kilometres), it’s no slouch, either. What’s more, being launched from a fighter, it is more flexible to use. Flexible, but not the cheap option. According to the Moscow Times, it is seen as playing a variety of rôles in any theatre of war, not simply as a way to conduct a nuclear exchange. It concludes “Hence, official statements claiming that it carries a 2-megaton nuclear warhead, or is invulnerable, should be taken with a large grain of salt.”

Having said that, with an estimated range of some 2,500 miles (around 4,000 kilometres – Russia claims considerably more), an Avangard could reach London from Moscow, which gives Russia an impressive range of possible targets. It would be not just a case of “goodnight Vienna”, but also goodnight Paris, Rome, London, Ankara and Baghdad. We have to hope Putin doesn’t decide to put that to the test. Many are concerned, though, that Russia’s militarisation has accelerated since its invasion and annexation of Crimea. What does it mean?

ARMS RACE GAINS SPEED

One thing it means, perhaps, is over-optimism on the part of Putin. The vast programme of weapons development and deployment was predicated on massive economic growth that hasn’t happened. Russia’s defence budget for this year (2020) was projected to reach $200-billion (€180-billion), which would require a growth in GDP of $5-trillion (€4.5-trillion), more than twice as large as the growth in, say, 2012. Russia’s economic forecasters were assuming growth similar to China’s, which it is far from reaching. In fact, Russia’s year-on-year GDP growth stood at 1.2% in February, 2020, compared with China’s 6.1% and America’s 2.3%. Russia’s actual defence budget was smaller (but still impressive – and worrying) at just under $60-billion (€54-billion). It was always Stalin’s belief – and Putin shares it – that the defence sector drives economic growth and must therefore grow. It was not a doctrine shared by US President Dwight Eisenhower, who was very wary of the military-industrial complex and its sometimes-baleful effect on the economy. He warned against it. Money spent on very fast missiles cannot then be spent on roads, hospitals, schools or other infrastructure, which worried him. It’s not something that seems to worry today’s leaders.

Putin has correctly claimed that Russia is the first country with hypersonic weapons already in its arsenal and has boasted to his own military chiefs that the rest of the world is now playing catch-up. He’s right, but probably not for very long. Both the United States and China are working on hypersonic weapons of their own.

America seems to be pinning its hopes on the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) while Lockheed Martin is developing the Falcon Hypersonic Technology Vehicle 2 (HTV-2). By 2011, the first AHW was ready for trial and in a test launch from the Pacific Missile Range Facility in Hawaii, it accurately struck a target in the Marshall Islands, 3,700 kilometres away. Like the Avangard, it uses boost glide technology, although it carries a conventional, rather than a nuclear, payload. The US sees the AHW and HTV-2 as providing it with the capability for “Prompt Global Strike”: the ability to launch a hypersonic missile against a target anywhere in the world in less than one hour. Neither is believed to be quite as fast as the Avangard. Russia is also cooperating with India in developing a hypersonic cruise missile, the BrahMos-II, while the US and Australia have tested an experimental hypersonic missile as part of their joint HiFiRE programme.

China, meanwhile, has been developing its own hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) alongside a hypersonic cruise missile known as the DF-ZF, which has already undergone field tests and which featured in last year’s military parade in Beijing. It can carry conventional or nuclear warheads, reach speeds of nearly Mach 10 and, like the Avangard, can manoeuvre to avoid anti-missile missiles when it gets near its target. China claims it is sufficiently accurate to use against ships at sea. It is also developing a new missile, the DF-17, which combines hypersonic capability with a ballistic missile, reaching speeds of Mach 10 but with a range probably limited to between 1,100 and 1,500 miles (1,800 and 2,400 kilometres).

Research into hypersonic weapons is not new: work was being carried out in the Soviet Union some three decades or more ago, but it has accelerated since the United States walked away from the anti-ballistic missile treaty in 2002. Russian military planners feared that the Americans might have a breakthrough in missile defence technology, which hypersonic weapons could overcome. According to the Moscow Times, “They do not fundamentally alter the modern character of war, but exacerbate longstanding trends in the drive toward greater speed and penetrating power, making defence a cost-prohibitive proposition. They help move the needle toward war between major powers being even more offence-dominant than it already is.” In other words, they increase the likelihood of somebody pressing the launch button first on the grounds that attack really has become the best – even the only – means of defence. If that attack uses nuclear weapons, the outcome would, of course, be disastrous for humankind. As Albert Einstein wrote in 1946, “The unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.”

NUCLEAR NERVOUSNESS

US defence experts believe that Russia retains up to 2,000 tactical (low yield) nuclear weapons of varying types that can be launched from land, ships, submarines or aircraft. They even have nuclear depth charges. Putin himself seems extremely keen on nuclear weapons, if only to prove that Russia remains a force to be reckoned with. He has been boasting of exotic new weapons systems that are unique and unparalleled, such as the Burevestnik, a nuclear-propelled cruise missile, delivering a nuclear payload. Its small nuclear reactor power source should give it – theoretically – an unlimited range. According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, it’s more to do with swaggering on the world stage that with defending Russia. “These exotic systems have more of a political function than a strategic or security one,” argues a website article. “Their role is to signal Russia’s continuing scientific and military prowess at a time when the country does not otherwise have much on offer. Devilishly expensive and sometimes dangerous to operate, they are unlikely to be deployed in big numbers, as a fatal testing accident of the Burevestnik in 2019 shows. If US-Russian arms control remains in place, such systems definitely will not be deployed in big numbers, because they would displace proven and highly reliable intercontinental ballistic missiles in the Russian force structure”.

The explosion happened at a Russian navy range on the White Sea, killing five nuclear engineers and causing fears of radioactive contamination in a neighbouring town. Both the United States and Soviet Union experimented with nuclear-powered missiles during the Cold War but abandoned them, largely because they were unsafe. They’re also extremely expensive, which means Putin is unlikely to see them as a regular part of Russia’s arsenal, even if his technicians can construct a Burevestnik that doesn’t blow up on the launch pad.

If all this posturing reminds you of your old school playground, you’re probably not far wrong. For school bullies, bombast was usually more important than blows. And to be perfectly honest, Putin is not exactly alone in trumpeting his military capacity. Donald Trump and Xi Jinping have also been guilty of bragging about their strength and their available weapons. Other nations – not many – also have a nuclear capacity (and quite a few more would very much like to) but they lack the means to be a thoroughgoing global nuisance. Their powers are regional, even if North Korea has resumed testing its short-range ballistic missiles into the Sea of Japan from the coastal town of Wonsan. Even so, Kim Jung-un and his ilk are relative minnows; Putin, Trump and Xi Jinping are the only sharks in the pool. Putin insists that his country’s development of new weapons is not to start a war but to maintain “strategic balance” and “stability”. In an interview with the TASS news agency, he said “We are not going to fight anyone. We are going to create conditions so that nobody wants to fight against us.” One assumes nobody really wants to fight anyone else anyway, except for a few religious or nationalist fanatics; war is rather a big step from diplomacy. Putin told TASS that Russia has created “offensive strike systems the world has never seen.” In view of the cost and doubts over reliability, there are good reasons why the world has not hitherto seen their like.

Col. Gen. Oleg Salyukov :

“Other countries

will not be able to design a rival to

Russia’s Iskander-M mobile

short-range ballistic

missile systems before 2025” © mil.ru

SPLITTING MORE THAN THE ATOM

The peace campaigning body, the Ploughshares Fund, quotes former UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon and Mary Robinson, the first woman to be elected President of Ireland, on their fears for the future, especially over nuclear weapons. “The two biggest nuclear powers, the United States and Russia – their relationship is not a good one,” explained the ever-charming Ban. “They are not talking to each other about how to deal with a lack of nuclear disarmament architecture.” Both Ban and Robinson are leaders of The Elders, a group of senior political figures working together for peace and human rights. They were in Washington for the setting of the so-called Doomsday Clock, an annual event organised by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. This year, the clock was set to 100 seconds to midnight, the closest it has been since its inception in 1947. Bear in mind that the Cuban Missile Crisis took place during that time. Ban fears that Russia and America simply don’t try to understand each other. “Their relationship has been shrouded in mistrust, denial, and counter-argument,” Ban continued. “I’m very concerned about a situation where nuclear wars and conflict can happen.” Robinson agrees: she sees climate change and the threat of war between the two countries as the biggest threats to our future. According to the Ploughshares Fund, the Elders have released a plan that calls for the nuclear-armed states – particularly the United States and Russia – to commit to never using nuclear weapons first, taking as many weapons off high-alert as possible, culling numbers of deployed warheads, and finally reducing global stockpiles overall. “We know that this is not the full answer, but if we could do that, we’d have a much safer world,” explained Robinson. “At the moment, we’re going the other way. We’re in a new nuclear arms race. We’re talking about hypersonic missiles. We’re talking about a space force and we’re talking about satellites being attacked. It’s very scary.”

Scary indeed: there is a theory that the very possession of such weapons is an incentive to use them. Back in 1967, the then US Secretary of Defence, Robert McNamara warned that “There is a kind of mad momentum intrinsic to the development of all new nuclear weaponry. If a weapon system works and works well, there is strong pressure from many directions to procure and deploy the weapon out of all proportion to the prudent level required.” This is especially worrying given that the new hypersonic weapons are only really likely to help win a conflict if used first, quickly and before the other side has begun to fight. It’s a case of shoot first and ask questions if there are any survivors.

Writing in a blog for the Foreign Policy Research Institute, Felix K. Chang, a Senior Fellow, expressed concern over the continuing tensions between Russia and Ukraine, which, in 2018, resulted in an attack by Russian forces on three Ukrainian vessels – a tug and two gunboats – in the Kerch Strait as they tried to sail from the Black Sea to the Azov Sea to reinforce Ukraine’s small naval force at Mariupol and Berdyansk. Six Ukrainian sailors were injured and twenty-three in all were arrested by the Russians. “Russia had already begun to strengthen the forces in its Southern Military District, which spans from near Volgograd to Russia’s border with Georgia and Azerbaijan,” Chang wrote. “Naturally, that has caused concern in Kiev, since the district also abuts the restive eastern Ukrainian region of Donbas and is responsible for Crimea, which Russia annexed from Ukraine in 2014.”

Tank to Enter Service in 2020 © Wikipedia

Chang points out that one of Ukraine’s biggest worries has been Russia’s reactivation of the 150th Motorized Rifle Division in late 2016. “Posted only 50 km from the border between Russia and Ukraine, it is equipped with an unusually large number of tanks. Its force structure includes two tank regiments, rather than the standard one; and each of its two motorized rifle regiments has an attached tank battalion. Russian media refers to the division as the ‘steel monster’.” The build-up of Russian forces has accelerated recently, however. In January, 2018, Russia’s Southern Military District comprised 415 tactical aircraft and 259 helicopters. A year later, the numbers had swollen to more than 500 tactical aircraft and 340 helicopters, whilst according to a senior Ukrainian commander, the number of Russian army battalions within easy reach of the frontier jumped from eight to twelve. And that’s not all. Chang writes that Russia’s biggest investment in its Southern Military District has been in air defence. Two years ago, it announced plans to build a Voronezh-M over-the-horizon early warning radar system near Sevastopol in 2019. “In late 2018, Russia sent one of its most advanced A-50 airborne early warning and control aircraft to Saki Air Base in Crimea,” says Chang, “which is home to dozens of Russian Su-30 fighters as well as Su-24 attack aircraft. Perhaps most striking of all, by the end of 2018, Russia had concentrated at least five of its most advanced S-400 air defence batteries in and around Crimea. Together with two other S-300 air defence batteries nearby, Russian land-based air defences in the region could simultaneously launch as many as 192 surface-to-air missiles.” Chang reports that their crews have been training not only to counter enemy aircraft but also to tackle ship-launched cruise missiles, making the Crimea and Donbas region among the most heavily-defended in the world. Many western observers wonder why, if Russia really has the peaceful intentions Putin claims, is he so massively building up his forces there?

ON YOUR MARKS, GET SET

Of course, the United States and China have not been sitting idly by as Russia steps up its capabilities for war. The China Academy of Aerospace Aerodynamics described the August 2018 test flight of its Xingkong-2 ‘waverider’ hypersonic cruise missile in glowing terms. The wedge-shaped vehicle, it’s claimed, separated from the rocket that launched it, coasting towards its target at speed of up to Mach 6, bobbing and weaving through the stratosphere, “surfing on its own shockwaves”. No video evidence of the test was released, but the Communist Party’s newspaper, Global Times, said that it meant the new weapon would be able “break through any current generation anti-missile defence system.”

The United States is conducting research into ways to defend against hypersonic weapons, whilst also working on its own versions. Experts agree that chasing them would be a tall order, so researchers are also investigating directed-energy weapons: lasers, neutral particle beams and microwaves or radio waves. Directed-energy weapons were part of the US ‘Star Wars’ military defence scheme back in the 1980s. They were found to be impractical then but four decades later they may be a more realistic bet. The US has, however, abandoned plans to build and test a 500-kilowatt airborne laser and a space-based neutral particle beam. It all begins to sound as if we’re entering Gene Roddenberry territory: ahead warp factor one, Mr. Sulu.

Not all of Russia’s new arsenal is either nuclear or even hypersonic. There are new conventional weapons, too, like the PAK-FA fifth generation fighter, or Perspektivniy Aviacionniy Complex Frontovoi Aviacii, to give it its full name. It’s a multi-rôle aircraft with stealth design to minimise its radar visibility and it can carry six long-range air-to-air or air-to-ground missiles and bombs. Several of these aircraft are already in service and by 2040 there will be up to 450 of them.

Add to that the PAK-DA Poslannik long-range strategic stealth bomber, built by Tupolev. Then there’s the four-engine swing-wing Blackjack Tu-160 bomber, capable of delivering its payload by flying below enemy radar, armed with the new Kh-101 long-range cruise missile. Just in case war should ever break out between Russia and China, there’s the next-generation tank for the Russian Ground Forces, the Y-14 Armata is a replacement for the T-72/T-80/T-90 series of tanks. It is a totally new design, bigger, heavier, with more protection and better armament, ideal for rapid counter-attacks into Manchuria. The T-14 outclasses China’s frontline Type 99 tanks, which are based on an older design. Armour appears to be composite laid out in a modular fashion, making it easier to repair. Weapons include an improved 125-millimeter main gun, 12.7-millimeter remotely operated machine gun and 7.62-millimeter coaxial machine gun.

There are more items on Putin’s list, although he insists it’s not about brinkmanship, sabre-rattling or threats, merely an issue of defence.

Russia has, in the past, accused NATO of warmongering by increasing its military presence in the Baltic. NATO has always argued that it is only in response to aggressive remarks from Moscow about Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Valery Gerasimov, the Russian military’s Chief of General Staff, has said that the Alliance’s troop movements, exercises and missile units point to an “intention to go to war”. Meanwhile the European Union has always sought friendly relations with Russia, even having a delegation to monitor political life in the country over issues such as human rights, justice, freedom and security. According to the European External Action Service (EEAS), Russia remains a natural partner for the EU and a strategic player combating the regional and global challenges, despite the freeze that settled in after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and its support for separatists in Eastern Ukraine. Although some of the contact mechanisms remain frozen, the EEAS remains theoretically hopeful of better relations. “Both the EU and Russia,” says its website, “have a long record of cooperation on issues of bilateral and international concern including climate change, migration, drugs trafficking, trafficking of human beings, organised crime, counter-terrorism, non-proliferation, the Middle East peace process, and protection of human rights. Furthermore, the EU develops a range of informal operational contacts that allow for a detailed understanding of Russian priorities and policies on international issues, provide early warning of potential problems and support the coordination of policy planning.” Members of the Russian Duma have returned to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe after walking out in protest over the Assembly’s condemnation of its actions in Crimea. The decision in June 2019 to re-admit the Russian members and restore their voting rights, was controversial: Ukrainian members immediately walked out in protest and there were scuffles between Russian and Ukrainian journalists when the Russian delegation returned.

LESSONS LEARNED

Reform and restructuring of Russia’s military began in earnest in 2008, after Putin temporarily stepped down from the presidency to meet the demands of the constitution, assuming the rôle of prime minister instead, while Dmitry Medvedev kept the presidential chair warm. This coincided with Russia’s disappointing performance in its war with Georgia in August that year.

Reforms were steered through by Anatoly Serdyukov, who was defence minister at the time. Rumours of corruption began to circulate, however, and Putin chose to replace Serdyukov with Sergei Shoigu, seen as a ‘safe pair of hands’. Putin reappointed Shoigu earlier this year, making him the longest-serving head of the defence ministry since the fall of the Soviet Union. Shoigu gets on very well with the Chief of the General Staff, Army General Valery Gerasimov and he has been praised in the pages of Komsomolskaya Pravda by retired colonel Viktor Baranets, one of that newspaper’s columnists. In the article, Baranets said that Russia’s armed forces had benefited under Shoigu from his continuing reforms and from the operations carried out in Syria in support of Bashar al-Assad. He also highlighted another important factor: Shoigu has an excellent relationship with Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov, who’s responsible for overseeing the defence and space industry. Strangely, perhaps, the article makes no reference to the conflict in Ukraine. There is no doubt, however, that Shoigu, working in tandem with Borisov, has made a difference to the modernisation of Russia’s armed forces. Baranets points out that when Shoigu originally took up his post, only 10 to 15% of Russia’s weapons were new. That figure is now around 70%. Meanwhile, the new Prime Minister, Mikhail Mishustin is making the further development of defence manufacturers a key priority. Shoigu is one of the survivors of Putin’s recent re-shuffle, and this may be as much to do with his network of contacts as with his actual achievements. His partnership with Borisov ensures a close link between the defence ministry and defence industries.

One observer, Fredrik Westerlund, deputy research director and co-editor of the report ‘Russian Military Capability in a Ten-Year Perspective – 2019’, wrote that “Over the past ten years, Russia has bridged the gap between its policy ambitions and its military capability.” Analysing Russia’s armed forces, their arsenal and their fighting power, as well as the effects of political and economic factors, the report finds that “the impressive pace of improvement of Russia’s Armed Forces in the past decade is probably not sustainable. Instead, the next ten years will consolidate these achievements, notably the ability to launch a regional war. Strategic deterrence, primarily with nuclear forces, will remain the foremost priority.” Project manager and the report’s co-author, Dr. Gudren Persson, adds that “The current trend in Russian security policy indicates that the authoritarian policy at home and the anti-Western foreign policy will continue. We’re in for the long-haul of confrontation with the West. We can also expect a recurrent use of armed force and other means to sustain its great power ambitions and protect Russian interests abroad.” Putin often accuses NATO and the United States of trying to push Russia into an arms race its economy will never let it win, but this is misleading. With Putin at the helm, Russia is more likely to follow a strategy that will be more than enough to provide for Russia’s defence.

But while Russia gears up for a war Putin says he doesn’t want, it’s worth remembering a few facts. As the EEAS states, the EU remains a key trading partner for Russia, representing in 2018 €253.6-billion and 42.8% of Russia’s trade. Russia is now the fourth largest trading partner of the EU for trade in goods, representing 6.4% of overall EU trade. Russia is also the fourth export destination of EU goods (€85.3-billion in 2018) and the third largest source of goods imports (€168.3-billion in 2018). Imports from Russia to EU increased by 16.7% from 2017 to 2018 and was driven by the growth of imports of energy products from Russia that account for some 70% of imports from Russia to the EU. In the first half of 2019, EU-Russia trade has to a large extent remained at the same level, compared to the first half of 2018. The same can be said of EU exports to Russia. But Russia cannot afford to be unaware that it is not as wealthy as, say, China. Its GDP in 2018 was $165,290-million (€148,761-million); China’s was $13,368,073-million (€12,031,265-million). Russia is rich in natural resources and its people could be better off, enjoying the advantages nature has generously provided to their country, as Anton Chekhov wrote in the Cherry Orchard, from which the title of this article is a quote: “The Lord God has given us vast forests, immense fields, wide horizons; surely we ought to be giants, living in such a country as this.” Indeed so, but not, perhaps, if you spend it all on weapons.

T. Kingsley Brooks

Click here to read the 2020 April edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine