Lithuanian conscripts © kariuomene.lt

This is an article I never expected to be writing. At least, I hoped I wouldn’t be called upon to do so. Human ambition being what it is, however, things we thought we’d left in the past can return to haunt us, and such is the case, it seems, with conscription. I’m sure everyone knows what it is, even if they felt confident that they’d never have to experience it in person. But, as the old saying goes, “The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men Gang aft agley”, (Scottish dialect meaning “often go wrong”). The expression comes from a poem by Robert Burns, all about a mouse. But mice going to war probably wouldn’t raise as many eyebrows as armed battalions and entire nations doing so. Who cares about a handful of small rodents (apart from other small rodents, I guess)?

In case you still harbour any doubts as the actual meaning, conscription means the forced recruitment, mainly of young men but sometimes of young women, too, into their country’s armed services in order to fight a war, or at least to be ready to if necessary to do so, either in defence of their homeland or in the hope of enlarging it by snatching bits of someone else’s. I’m sure most civilians hoped it would never come to this, but now, as the threat of a real shooting war looms closer and closer it may be something we simply won’t be able to avoid as an issue that has been consigned to history. Conscription itself (or recruitment by force or coercion if you prefer) is nothing new. It dates back to the Egyptian Old Kingdom, possibly as far back as 2600 BCE or so. Some leader finds himself (or herself) in need of some people to defend his or her kingdom and you simply round up a bunch of civilians, put swords and spears in their hands and having indicated clearly to them who exactly is the enemy you point them in that direction. You don’t want to see them running towards others on your own side, shouting insults and threats. Once they know which side they’re on it should be fairly easy, even for the simplest civilian.

Now it seems that conscription is on the way back. The President of Latvia, Edgars Rinkēvičs, has warned that the countries of Europe really need (he said “absolutely”) to reintroduce conscription in order to face up to Russia’s endless aggression over Ukraine. President Rinkēvičs said the other countries of Europe should follow Latvia’s lead, even though most had put a stop to conscription when the Cold War ended, although he understood why people may be ‘a little bit nervous about the idea’, adding that “strong reassurance is one thing, but another is the real action being taken by the Latvian government”. Latvia itself brought back compulsory military service in January, although its need may be more urgent than it is for some other countries, since it has a direct border with Russia that’s very nearly 290 kilometres long. Furthermore, the decision came just five months after Russian troops entered Ukraine. With US President Donald Trump’s threats about the security guarantees for Europe that were put in place some 80 years ago, there is a growing sense of alarm. If it were to happen for real, it is not the sort of development to be lost on Russia’s own ambitious President, Vladimir Putin.

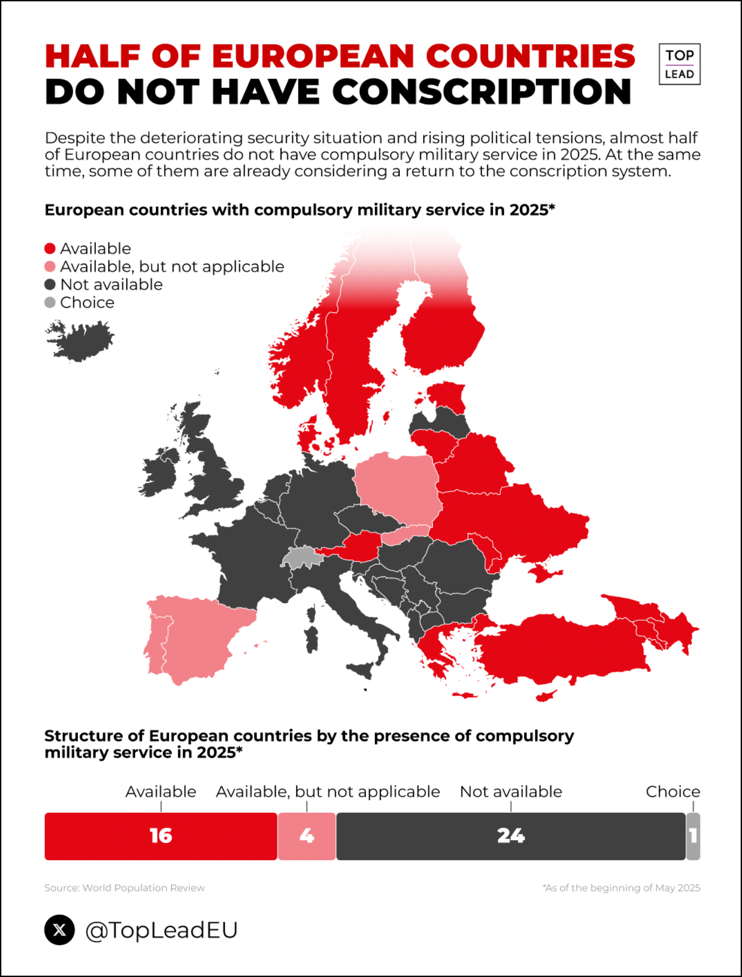

It will have raised eyebrows in Europe, too. Several countries, especially in Scandinavia and the Baltics, have already reintroduced conscription, having been alarmed by Russia’s growing threats and the size of its armed forces. “Today’s Russian military,” says Alexandr Burilkov, a researcher at the Institute of Political Science at Heidelberg University, “is larger and better than it was on February 24, 2022”, adding that: “The Russians have hostile intent against the Baltic States and the EU’s eastern flank.” A study Burilkov co-authored for the Bruegel think tank at the Kiel Institute estimated that Europe may need an extra 300,000 troops to deter Russian aggression, in addition to the 1.47-million personnel it already has on active service. Burilkov thinks that conscription could prove vital in reaching such numbers, especially as some countries, including France and the UK, have struggled to recruit troops, which means that reintroducing some form of compulsory national service could prove unpopular and therefore difficult. This is surprising, given that a large majority of French people are in favour of compulsory military service, according to a report published by Ipsos-CESI Engineering School. A YouGov poll suggests that some 58% of Germans support the idea for young people, although Italians and the British are divided on the issue and most Spaniards oppose it. If, as a young person freshly out of college you have plans for a peaceful but rewarding career of some sort you won’t want to have those plans knocked off course while you are being trained to kill people you don’t even know. Lithuania reintroduced conscription in 2015, just a year after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, with Sweden doing likewise in 2017 and Latvia in 2023. It was the first European country to do so. A French expert, Benedicte Cheron, has said that it would be all but impossible to impose military constraints at present. That would almost certainly change, however, in the case of an invasion.

The sight of T-72BM ‘Ural’ tanks rolling across their green and pleasant lands would probably stiffen the sinews somewhat. Nine European countries – Greece, Cyprus, Austria, Switzerland, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Norway and Turkey retained compulsory conscription when the Cold War ended, although France, Germany, the UK, Poland and Italy – NATO’s biggest spenders – have no plans to bring it back. Not yet, anyway.

Being in the military has some advantages for conscripts, it’s claimed, with a uniform of some sort proving attractive to the opposite sex. “All the nice girls love a sailor,” ran a line in the 1909 musical, Ship Ahoy. In most cases involving the sailors I’ve met, I think their preferences would probably be for girls that are unlikely to be described as “nice” in the normal sense. As that song also points out at one point: “well, you know what sailors are”. Yes, quite. I blame all those long weeks at sea with only male company. Even so, the apparent appeal of a smart military uniform may not be enough to overcome a natural built-in resistance to discipline and to placing oneself in the firing line. Poland, the invasion of which by Germany launched the Second World War, ended conscription in 2008 but has recently announced plans to offer military training to some 100,000 civilians a year, beginning in 2027. It will be a voluntary scheme, according to Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, but with a system of what he called “motivations and incentives” as inducements to sign up. Exactly what those are has yet to be specified, but it has to be something more enticing than Green Stamps.

Within the EU, it was commonly believed that conscription had been consigned to the history books, but Russia’s apparent taste for expansionism is changing public opinion. Take the EU, for instance, where defence policy is now under serious discussion and was the subject of a report in 2024 by the former Finnish President, Sauli Väinämö Niinistö.

Opinion polls in several EU countries have been showing a growing support for either the reintroduction of national service or for full-blown conscription. We must bear in mind that the EU was not set up with a view to militarism. It’s basically a trading club, facilitating cross-border trade by setting common standards in terms of health, hygiene and working standards. Despite the claims of its manifold critics, its aims are simple and peaceful Since the UK left it, certain products have been harder to find in the British shops. It’s hard to see the improvements to life promised by Brexit’s supporters and cheer leaders, such as the leader of the far right Reform party, Nigel Farage, who wants to become Prime Minister, and the opportunist Boris Johnson. Looking across the EU, existing conscription policies differ from country to country. I was lucky in the UK, being just too young for the last call-up in 1960 (I was 12 years old that year), although one of my cousins seems to have quite enjoyed his period of miliary service. Today, conditions vary across the EU’s member states, imposing different periods of service, differing sums of financial compensation and also retaining differing numbers of reserve forces. Niinistö’s report pointed out the potential advantages if his “total defence” concept, while promoting what he called a “whole of society” approach to crisis response and defence preparedness.

Many people don’t realise that the EU has a Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), and while some point out the advantages of conscription, others remain unconvinced that a defence force primarily made up of what are often poorly trained and ill-equipped amateurs with guns will save Europe from a takeover by Vladimir Putin. It’s different in Italy, where Matteo Salvini’s bill is intended to introduce compulsory military or civilian (an interesting definition, that) service of six months for all 18- to 26-year olds.

The growing power of far-right governments such as Italy’s Lega means an increasing interest in conscription across much of Europe. Italy abandoned conscription in 2005. Spain abandoned it in 2001, France in 1996, Germany in 2011, Belgium in 1994 and the UK as long ago as 1963. There is no national army in Iceland and there has never been compulsory military service in Ireland. Popular opinion is changing, however, along with the reality on the ground, although far right politicians like little better than to have their young men in uniforms stamping around and carrying guns.

It’s very different in Spain, where even the parties of the far right find they must avoid the subject of conscription. Its reintroduction hasn’t even crossed anyone’s mind, according to Defence Minister Margarita Robles, who is also a judge. Sociologist Rafael Azangith, formerly a professor at the University of the Basque Country, has written several books about military issues and on conscientious objection. With any conscription system, however, you inevitably get people who will find ways to avoid it. During the Vietnam War the Americans called then “draft dodgers”. But it’s not just a matter of right and left disagreeing about compulsory military service, according to Alberto Bueno, professor of political science at the University of Grenada and considered an expert on military issues. Having a left-wing government won’t necessarily save you from being called up to serve. “In countries that feel threatened, for example,” he said, “even social-democratic parties are in favour of reintroducing military service.” The percentage of the population in the Czech Republic that supports military service has risen since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it is still well short of a majority view and no party seems to in favour of it. Bulgaria dropped conscription in 2007 and has no plans to reintroduce it, it seems, although military training for civilians is under discussion. Six months of military service for men remains compulsory in Austria, as has long been the case. That may be because the population of Austria is just a meagre nine million, and there has not been a strong military tradition there since the end of the Second World War.

Austrians have not forgotten either the country’s civil war during Europe’s inter-war years, when soldiers under the control of the Conservative Party opened fire on members of the Labour Party. It’s not a good way to win elections, and as a result, the idea of a professional army without universal conscription has been ruled out by parties of virtually every persuasion. It’s different again in Finland, where military service is compulsory for men between the ages of 18 and 60 and optional for women, too, between the ages of 18 and 29.

Of course, at the end of the day it may well not be the number of conscripts a country has assembled that decides the outcome of a war. It may, and more probably will, be decided by the power and efficiency of your nuclear arsenal and the range and accuracy of your delivery system. Russia, it seems, likes to brag about just how effective its nuclear weapons are. It’s claimed that one particular set of messages it put out made clear that Britain and France would be Moscow’s primary targets. One of Putin’s merry men is alleged to have claimed the efficacy of one particular type of Russian missile by saying: “One Sarmat (the missile in question) means minus one Great Britain.” It’s a rather clumsy way to put it, but I suppose English is unlikely to have been his native language and diplomacy not his strong point. Nuclear arms have not been used in an international conflict since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki towards the end of the Second World War. I imagine most people hoped they’d never be used again, but humankind being what it is that may prove to have been a vain hope.

We should remember the experience of one 13-year-old Japanese girl, Setsuko Thurlow, who had the misfortune to be less than two kilometres from the spot where the world first saw an atomic weapon used in anger. “Little Boy”, as the weapon was ironically named, exploded less than 600 metres above the Japanese city of Hiroshima, ensuring that unhappy city’s permanent place in history. Incidentally, according to Annie Jacobsen’s excellent but terrifying book “Nuclear War – a Scenario” Little Boy was just 3.5 metres long and weighed 4,400 kilos. Young Setsuko survived but could neither see nor move for some time. Back then there were no missiles capable of carrying such a load, so it was dropped instead from a military aircraft. Ah, the ingenuity of the military mind!

If you’re looking for a positive angle to emerge from the carnage, at least it probably means that compulsory conscription is less likely. The reason Putin has such a down on France and the UK, it seems, is that he accuses both countries of leaking his military secrets to Russia’s enemies, raising the question of where and how they obtained them. By that, I presume he means they may have leaked military secrets of some kind (of exactly what kind I cannot imagine) to those countries opposed to Putin’s intention to seize all or parts of all the countries that are not currently under the control of Russia. He seems to think Russia should own everywhere. It would certainly add piquancy to him singing that song “If I Ruled the World”, if he should ever choose to do so, because unlike the character in the musical, Pickwick, from which the song came, Putin really would like to rule the world and apparently thinks he should. Pickwick is, of course, based on the Charles Dickens 19th century novel, the Pickwick Papers. The song continues: “If I ruled the World, every day would be the first day of spring”, whereas I rather suspect that the Putin version would go: If I ruled the world, every day would be the end of it all.” It’s an odd way to view the planet Earth.

But back to the topic of conscription. Ukraine is trying to recruit young Ukrainians, aged 18 to 24, to join the fight against Russian forces for one year. Kyiv is promising quite a sizeable salary, plus a generous bonus and an interest-free loan to help with a house purchase, assuming they survive long enough to get it. It won’t be an easy sell, but in a country under constant drone attack it will undoubtedly get takers. Putin is not popular there, nor ever has been. It was in the streets of Kyiv that I bought from a street trader a roll of lavatory paper with Putin’s picture on every sheet. The pictures have sadly faded somewhat in the years since, although Putin in person, sadly, has not. Since the war began in earnest, Ukraine has been engaged in a major recruitment drive but has only succeeded in signing up some 500 or so would-be recruits according to Pavlo Palisa, President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s military adviser.

Europeans are nervous following US President Donald Trump’s insistence that they must look to their own defence. The United States (under Trump, at least) won’t help them. The UK has so far ruled out conscription, although the country has increased its defence spending. In Italy, meanwhile, Defence Minister Guido Crosetto has ruled out reintroducing national service but has spoken in favour of creating a reserve force. We should not, perhaps, blame Vladimir Putin for everything; he has surrounded himself with advisors who are in the main conspiracy theorists. Putin himself, partly as a result, sees enemies wherever he looks, most of them plotting his downfall. He certainly dislikes the United States. He once said: “America does not need allies, it needs vassals”. Wherever there are flare-ups and conflicts, he refuses to accept that they’re examples of resistance to corrupt governments. He believes they’re all CIA plots aimed at bringing down any governments that are sympathetic to Moscow. And, as I said, he believes all those conspiracy theories his war-mongering supporters believe. One of Putin’s closest advisors, Nikolai Patrushev, secretary of Russia’s Security Council, has said that the United States “would very much like Russia not to exist as a country”. He seems to believe that the West is just awaiting an opportunity to invade. Well, Vlad, you’re wrong, and you should not allow such fantasies to inform your decisions.

According to Mark Galeotti in his fascinating but worrying book, “We Need to Talk About Putin” believes that the “great powers” must have sphere of influence. There can be no real “independence”. That’s why he “punished” Georgia and Ukraine: he saw them as trying to get closer to the West.” Incidentally, as a reader of histories interested in the nineteenth century in political terms, he sees global influence as a reflection of real power. He believes, of course, that Russia itself is a “great power” and therefore that it should not regard itself as being constrained by international laws and agreements. And Putin, who is not very tall, always wants to seem to be a tough guy.

So here we are again, with an enemy whose animosity is based on a belief that his country should be in charge of everything, everywhere, and who is unwilling to consider peace, which he seems to see as a sign of weakness and an invitation to invaders. If he ever designed a computer game he could make a fortune, but such things lack real blood and bullets and bombs. No fun there, then, by Putin’s standards. Will it, can it all end peacefully? I don’t know. Certainly not if Putin gets his way and the West declines to stand up to him. Whether or not that defiance may rest on conscription and the willingness of ordinary citizens to fight is harder to predict. After all, Putin doesn’t seem to want to “keep the red flag flying here”; he’d rather simply subjugate the people of the world under his impeccable (in his view) rule. I hope he’s wrong.

Jim.Gibbons@europe-diplomatic.eu