© AI generated image

We have to face up to the fact that some people love war. Most of us are horrified by it and by its heavy toll of lost human lives, but for some militarily-minded people it’s the only game in town. The lives lost on all sides are, to them, an irrelevance, or, at best, a way of keeping score. At present, the West, as a whole, is not a participant in the conflict going on in the Korean Peninsula. Vladimir Putin most certainly is, even if his great predecessor, Joseph Stalin, would have disagreed. He gets on very well with his friends, the North Koreans, who seem to share his love of armed conflict. It now looks, however, as if the Korean War (1950-1953) is staging a come-back, for which the West is unprepared. North Korea, interestingly, is the only country capable of producing weapons for Russia, something it does rather well, it seems, while also supplying its own very efficient troops to fight on the front line. They’re apparently very good at that, too. We should, perhaps, remember the words of Abraham Lincoln: “There is no honourable way to kill, no gentle way to destroy. There is nothing good in war. Except its ending.” Sadly, that’s not a view that is universally shared, and certainly not in Rusia or North Korea.

I can remember a lot of talk about the Korean War when I was at primary school, but the East is a long way away, so what was going on there seemed to be largely an irrelevance in Europe. It wasn’t, of course; wars have a habit of spreading from country to country until virtually everyone is caught up in one. The fact remains that for world leaders engaged in such conflict it all seems to be justified. As Martin Luther King Junior said back in the days of the Vietnam War: “We have guided missiles and misguided men”. How true. At school, we heard talk about the Korean War without really understanding who the protagonists were nor what they were fighting about. With all our modern-day electronic communications, things are rather different today: we all know there’s a war going on but we know little more than that people in another country far away are busy killing one another.

Take the views of Andrei Lanko a professor at Kookmin University in Seoul. From there, he observes what is happening in the world, occasionally (and usually very wisely) commentating on what is happening. He has a wide range of followers among English- and Russian-speaking audiences. “North Koreans proved good soldiers,” he wrote, “and I think this is only the beginning. They are likely to be very good once they learn more about the technologies of modern war.” He knows what he’s talking about, so we can’t say we haven’t been warned. Russia-born Mr. Lankov pointed out that the bilateral partnership signed in 2024 between Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un is “purely transactional’, although it works in North Korea’s favour. According to sources among South Koreas intelligence services, North Korea has already provided Russia with up to 12-million artillery shells, while Putin also enjoys the military support of up to 13,000 North Korean soldiers. North Korea can certainly spare them: it has far more men under arms than even Russia can boast. In fact, it has the fourth largest army in the world, after China, India and the United States. It has an impressive 1.28-million men under arms. They’re not all what might be described as “crack troops”, but some 200,000 of them apparently are.

Mr. Lankov says that ideological differences among the fighters of China, Russia, Iran and North Korea should not lead us to doubt their determination nor their capability in the field. He likened today’s situation to the world in the 18thcentury, when virtually all alliances could have been described as “marriages of convenience”. He pointed out that back then – as is the case today – ideology counted for nothing, so Mr. Kim’s deployment of North Korean troops to Russia could be seen as being inspired by a love of money, rather than of Mr. Putin. But there again, most wars are inspired and sustained by financial greed. As far as Putin is concerned, North Korea’s willingness to fight his war for him is very important. He doesn’t want to have to fight a war using draftees, which could seriously damage his popularity and support. He prizes that, too. Certainly, Ukraine rates the North Koreans higher than their Russian equivalents; it believes them to be fitter, more aggressive, more cohesive and better marksmen that their Russian equivalents.

Even so, the North Korean troops have so far limited themselves to fighting on Russian soil, without venturing into Ukraine. A Moscow export believes that is likely to continue, at least for the time being. However, with Mr. Kim’s Koreans guarding borders, installations and sensitive sites, it frees up Russian soldiers to undertake the required aggression of Mr. Putin’s war. That may continue, but Mr. Lankov believes that if the war drags on much longer, then North Korean soldiers will be obliged to take their arms into Ukraine. Mr. Putin would prefer to avoid such a scenario, in case the presence of foreign forces, even Russia-loving North Koreans, would open the door for the entry of NATO troops on the other side.

For North Korea the traffic is not all one-way. Ukraine has noted an improvement in the accuracy of North Korean ballistic missiles, demonstrating a transfer of Russian technology. It’s also believed that Russia is passing on some of its drone-making expertise, especially guidance technology., while Russian air defence systems have been identified in North Korea, possibly together with naval propulsion and control technology. Russia is clearly enjoying its war and wants to see others getting their share of the enjoyment that goes with mass slaughter. Apparently, Russia is also passing some of its agricultural produce to North Korea which is geographically badly situated for agriculture. There’s another point we shouldn’t forget: North Korea’s soldiers are not as well paid as their Russian allies, so they’re cheaper.

I have read that Russian blogs, viewed in North Korea, carry references to Russian chocolate, canned foods and sausage, while the media in North Korea have been flagging up the health benefits of such things as wheat flour and baked goods that can only have come from Russia, and that traffic looks certain to increase. A new road bridge between the two countries is being constructed to augment the existing rail link. Mr. Lankov has stated that the roads leading to the border are rather rough and difficult for vehicles, especially those with cargoes to transport, so now flights are beginning between Pyongyang and Moscow, although they are unlikely to be carrying fuel. There is no natural gas being used in North Korea but there has been no discussion of constructing a pipeline, which would be very expensive, leaving Pyongyang reliant on Chinese fuel that comes through a dedicated pipeline under the Yalu River.

A labour force cannot be transported through pipes, of course, but with a shortage of civilian labour in Russia’s far East, some solution will be needed, and North Korea is not without a ready supply of workers, after all. The Philippines earns a lot of its foreign capital from exporting its civilian labour; the hands of its workers help to balance its books. Mr. Lankov reckons that North Korea could send as many as 300,000, or even 400,000 civilian workers to help meet Russia’s shortages. He believes that Russia really needs North Korea. Indeed, North Koreans and Russians are enjoyiny considerable prosperity at present, in much the same way as the Philippines makes a useful profit from exporting its much-needed workers. Some of the worst mistakes, however, have been on the West’s part. It could have (some would argue “should have”) mothballed NATO after the USSR collapsed, but instead it expanded it eastwards, putting the wind up Moscow for nothing.

Peace moves are under way, however. South Korean President Lee Jae Myung has pledged to improve his country’s strained relations with Pyongyang. Seoul is exploring the possibility of permitting individual tours to North Korea, which a spokesman for the Unification Ministry believes would be permitted under the rules controlling international sanctions.

Ironically, the whole country is suffering an infestation of what are called “love bugs” (plecia longiforceps, to give them their scientific name) but there still seems to be little love lost between the two countries. Perhaps both of them could learn from the bugs? As it turned out the conflict caused heavy losses of life that could have (should have) been avoided.

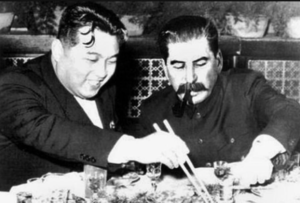

Up to three million civilians were killed, together with more than a million military personnel, all of them in the period from June 1950 to late July 1953. The conflict ended with an armistice but no formal peace treaty, so in a sense it could be said to be still going on. Joseph Stalin had warned Soviet representatives in North Korea back in May 1947: “We should not meddle too deeply in Korean affairs.” According to Oleg V. Khlevniuk in his biography of Stalin, Soviet troops began to withdraw in 1948, followed a year later by the Americans. North Korean leaders saw this as an opportunity, opening the door to military intervention. Stalin disagreed, however, and continually rejected the insistent requests for action, preferring to follow the principles of realpolitik. The North Koreans were disappointed and couldn’t understand the Russian leader, even suggesting that they might get Mao Tse Tung’s newly victorious Chinese involved. It never happened, partly because the North Korean leaders remained Stalin’s puppets. In any case, Khleviuk argues, even the Chinese relied on Soviet assistance, so the idea was never seriously considered. That being said, the idea of a Russia-North Korea alliance is a frightening one, according to Andrei Lankov (yes, him again). As he has pointed out, North Korea is the only country willing and, indeed, able to produce ammunition for Russia. Russia and North Korea together, he believes, are spearheading a “brutal new world order for which a weakened West is unprepared”. It seems that Mr. Lankov has a very high opinion of North Korea’s military forces. It may well prove to be a justified opinion, too.

For its part, South Korea seems increasingly keen to talk peace and to try to ensure it. But in reality that’s not what has been happening. Indeed, North Korea has accused its neighbour to the south of making the existing tensions worse by flying drones into its capital, building up existing tensions by dropping propaganda leaflets over Pyongyang, which the North warned could lead to armed confrontations.

The South warned that it would be willing to respond in kind in the event of enemy fire. Tensions, though, seem to be getting worse. There have been a number of exchanges between the two Koreas, with the tensions said to be worse than ever, especially since the North’s leader, Kim Jong Un declared early in 2024 that he views the South as his regime’s “number one enemy”. The north has claimed that the propaganda leaflets that have been dropped by the South’s drones contain “inflammatory rumours and rubbish”. Kim’s sister, Kim Yo Jong, who holds a lot of influence, has warned Seoul of what she called “horrible consequences” if the alleged drone flights were to be repeated. The North has yet to produce irrefutable proof that the drone flights actually took place, although it has produced photographs that it claims to be genuine. Kim Yo Jong claimed she had “clear evidence” that what she called “military gangsters” from the South were behind the drones and their supposed leaflets. Having initially denied sending drones over the North, the South’s Joint Chiefs of Staff later declined to either confirm or refute their involvement in the wave of drones. Looking at the claims and counter-claims, I have to say that the whole thing appears to be rather childish. Park Sang-hak, leader of the Free North Korea Movement coalition, denied having been involved in the drone flights, stating that: “We did not send drones to North Korea”. There has been a lot of sabre-rattling on both sides, although whether they would take the next step, without support from Washington or Moscow, remains far from certain.

All in all, these supposed peace overtures show little sign of making any difference, or even of existing. On the ground there is little or no evidence of a search for peace. The South has made clear its determination to put in place its effective self-defence plans. South Korea’s Joint Chiefs of Staff public relations officer, Lee Sung-joon told the media that the North could mount what he called “small-scale provocations” without provoking retribution, although shortly afterwards the North set off explosions along the Gyeongui and Donghae roads, which are regarded as being “symbolic”. Both roads had already been closed for quite a long time, but their total destruction goes significantly further. Expert Korea-watchers reckon it shows that Kim is not interested in negotiating with the South. The explosions themselves provoked the South into firing weapons on its side as a “show of force”, which probably also failed to provoke a response. Little boys arguing in a school playground would understand. The government of Gyeonggi Province, which surrounds the capital, Seoul, responded swiftly, designating the whole area as “extremely dangerous” and making it clear that scattering propaganda leaflets towards the North “could trigger a military conflict”, in the words of Kim Sung-joon. “The scattering of such leaflets,” he said, “could threaten the lives of our residents,” adding that in his view “inter-Korean relations are rapidly deteriorating”. It’s a dangerous part of the world and it has been for a very long time.

There seems to be little or no sign of matters improving any time soon. In 2024, North Korea announced that it would cut road and rail access between North and South, permanently blocking off the border while fortifying the area on its side, a move the Korean People’s Army (KPA) described as “self-defensive” with the aim of “inhibiting war”. The North blamed the decision on the allegedly frequent presence of American nuclear weapons in the border area and on military exercises by the South.. Tensions between the two Koreas are said to be at their most tense in years. It’s in reality more of a symbolic than a strategic measure because roads and rail links between the two Koreas are rarely used and have been incrementally dismantled by the North Koreans over the last couple of years.

Early in 2024, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un announced that he was no longer striving towards reunification with the South, which has raised fears that this long local cold war could be about to heat up again. He has also talked about revising his country’s constitution, deleting references to the northern or southern parts of one country and to such ideas as “peaceful reunification” and “national unity”. From the North’s perspective it seems clear that unification with the South is a non-runner. Nobody seems to know for sure which way the road to the future lies, but the prospect of a peaceful solution is not on the cards, it seems, any more than is a mutually acceptable co-existence. It’s thought that some of the prevarication was because nobody was sure of what would happen under a Donald Trump US presidency. His main concern seems to be China and its strategic position, as well as its growing power in the region. He wants South Korea to significantly increase its share of paying for US troops stationed near Seoul, as well as spending more on military expenditure. Meanwhile, both North and South are talking openly about live firing, which could be seen as dangerous talk. What’s more, while these demands by the US, aimed at advancing U.S. interests, could, some experts have argued, unintentionally destabilize South Korea’s government and drive Lee Jae-myung, the newly elected president, closer to China, the most formidable U.S. rival. The plain fact is that there is no love lost between the two Koreas; they dislike and distrust each other in equal measures. As for Russia, relations with North Korea are somewhat uneasy. Mr. Putin may not be opposed to a war in principle, but it would have to be on his terms.

Things have hardly been peaceful in South Korea, what with martial law, impeachments and vicious rows among the political parties and it’s unlikely that it will all end peacefully any time soon. The row over the presidency and who holds it looks likely to continue for some time yet. Reconciliation looks unlikely at the moment while the entire country is wracked by conspiracy theories which may make reconciliation all but impossible. Both of South Korea’s main political parties fear being overlooked. As much as they fear President Trump’s threatened (promised?) tariffs or a reduction in available US troop numbers to come to their aid, the politicians of the South seem unable to reach any sort of settlement. They have appealed to Washington for help, perhaps more in hope than expectation. After all, with only an unelected acting President, establishing any sort of meaningful relationship is no easy matter. The future has never seemed so uncertain or worrying since the full-blooded Korean war of the early 1950s. In a worst case scenario, we could be about to witness a full re-run.

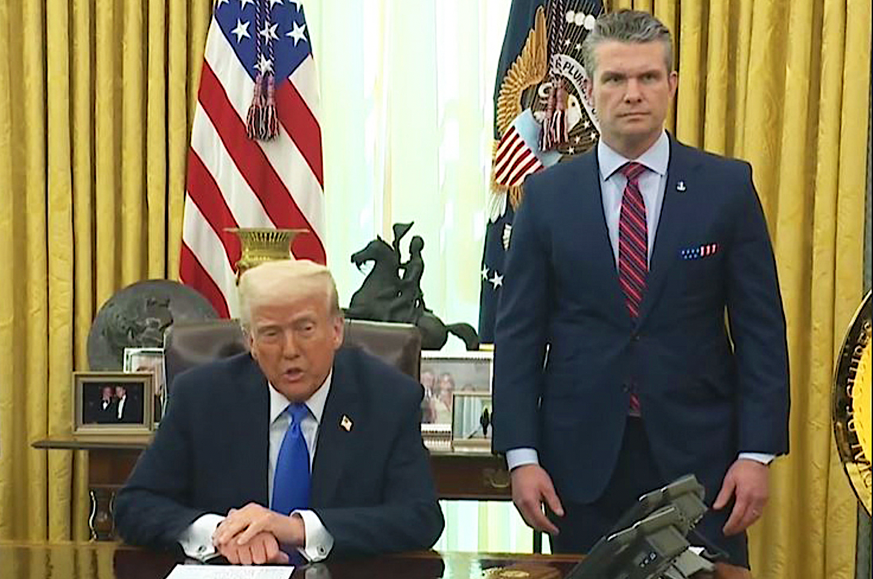

In South Korea itself, there is a growing fear of anti-Americanism over-shadowing the relationship and deeply affecting what happens next. It’s not looking rosy in the Korean peninsula. There have been misunderstandings, too. Comments by Donald Trump and his Secretary of Defence, Peter Hegseth, that North Korea is a “nuclear power” have been interpreted by some as meaning that the United States has abandoned denuclearisation as a policy goal for North Korea, which would represent a major policy shift. It’s almost certainly a misinterpretation. After all, denuclearising North Korea is not only a long-standing US policy, it is also a legal requirement of eleven UN Security Council Resolutions, as well as U.S. legislation, such as (among other things) the North Korea Policy Oversight Act of 2022. Japan, of course, also plays a key part in US defence policy for the region. Washington must surely realise that there can be no security negotiations without them. South Korea, along with Japan, is a stalwart security partner against perceived regional threats to peace. It’s easy for us in Europe to forget those places far away and their importance to world peace. We must not. Europe must work as closely as possible with Seoul and Washington to underpin peace wherever and whenever we can. After all, we’ve only got one world. We may not always agree with each other but we must avoid falling out in such a way that we blow it up, or allow others to do so, if we can avoid it.

Jim.Gibbons@europe-diplomatic.eu