Tomb of Napoleon, Church of the Dome at Les Invalides © Michael Espinola Jr

The authenticity of the Emperor’s remains, returned from Saint Helena, remains shrouded in the mysteries of history.

After abdicating on 22 June 1815 following his defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon initially planned to escape to the Americas with the aid of two frigates awaiting him on the Atlantic coast. Thwarted by the British blockade, he ultimately surrendered to the English. On 15 July 1815, they transferred him to Plymouth, England, and on 7 August, exiled him aboard the Northumberland to the remote volcanic island of Saint Helena. Located 122 km² in size, the island lies nearly 2,000 km from Namibia and over 3,000 km from Brazil.

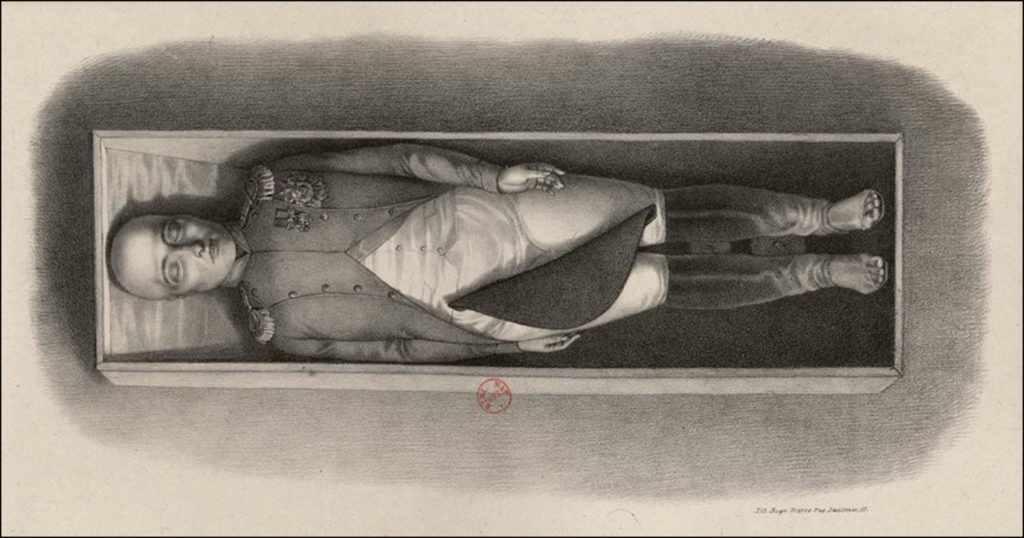

When the body was exhumed on 15 October 1840, it was noted with some surprise that Napoleon’s remains were in an exceptional state of preservation. This was particularly striking, given that during the autopsy performed the day after Bonaparte’s death on 6 May 1821, several conflicting reports and controversies had arisen. It is worth noting that Napoleon’s personal physician, François Carlo Antommarchi, was compelled to conduct the medical procedure, assisted by several British doctors, including Francis Burton, Archibald Arnott, and Matthew Livingstone.

The official report stated that Napoleon died from stomach cancer, though some later theories suggested possible arsenic poisoning. Dr. François Antommarchi, of Corsican origin and appointed by Napoleon’s mother, refused to sign the British autopsy report and instead wrote several conflicting documents. Napoleon was buried on 9 May 1821 and remained undisturbed for over 19 years, until the French mission exhumed his remains. Among the most notable figures in the delegation were:

- General Bertrand – Former companion in exile to Napoleon on Saint Helena.

- General Gourgaud – Another loyal companion of Napoleon.

- Baron Emmanuel de Las Cases – Son of Emmanuel de Las Cases, who had accompanied Napoleon to Saint Helena.

- Count of Rohan-Chabot – Diplomat and official representative of King Louis-Philippe.

- Dr. Guillard – French doctor tasked with assessing the state of the body.

- Prince of Joinville (François d’Orléans) – Son of King Louis-Philippe and commander of the expedition.

| The Mystery of the Body’s Preservation

The French delegation could not help but express astonishment at the exceptional state of preservation of the Emperor’s remains, nearly 19 years after his burial. This seemed particularly surprising, though some scientific explanations later attributed it to the climate of Saint Helena or the use of an airtight lead coffin. Nevertheless, this phenomenon quickly fueled rumours and theories in France, with some suggesting that Napoleon’s body had been substituted and others accusing the English of involvement. It is worth noting that the British initially opposed the exhumation of Napoleon’s body, fearing it would reignite tensions and strengthen the Napoleonic myth. However, Lord Palmerston, then Foreign Minister, eventually granted approval, albeit under specific conditions. After the necessary formalities, the coffin was resealed, placed in a new sarcophagus, and transported aboard the frigate La Belle Poule, which departed Saint Helena on 18 October 1840. No autopsy or scientific analysis was conducted at that time.

Since then, numerous theories have circulated, both in historical and scientific circles, some of which are grounded in concrete evidence.

| The Hypothesis of a Substituted Body

According to some accounts, the English may have substituted Napoleon’s body with that of his servant, Cipriani Francesco, who had committed suicide and was buried on the island in 1818. Cipriani had a similar physique to Napoleon and was considered by many historians to have been a spy working for the English. The reasons behind this theory are varied, but one claim, in particular, has captured the attention of those who believe in an English conspiracy. Some even cite the testimony of a descendant of one of the English officers stationed on the island, who claims that whenever she visits Westminster Abbey in London, her feet tread on the stones covering the Emperor’s remains. According to her, her ancestor had witnessed the repatriation of Napoleon’s body to England.

In 1969, a writer named George Rétif de La Bretonne published a book entitled “English, Give Us Napoleon Back”. In it, he argued that between 1821 and 1840, the British exhumed the Emperor’s body and replaced it with that of his butler, Cipriani, who had died on Saint Helena in February 1818. Rétif further claimed that Napoleon’s remains were secretly transferred to Westminster Abbey, where they lie under an unmarked and unidentified slab. To support his theory, Rétif referenced the report by Louis Marchand, one of Napoleon’s former valets who attended the burial, which mentioned only three coffins.

However, on 15 October 1840, when Napoleon’s body was exhumed for its return to France, the coffins were opened to verify the remains. All testimonies agree: four coffins were opened. According to Marchand, Napoleon had confided in him a few weeks before his death: “The only thing to fear is that the English will want to keep my body and place it at Westminster.” If there were three coffins in 1821 and four in 1840, Rétif argued, it was because Napoleon’s tomb had been opened in the interim to steal his body and replace it. Thus, according to several theories, George IV, King of England—who admired Napoleon but was also known for his eccentric and morbid tastes—secretly exhumed Napoleon’s body and substituted it with that of the Emperor’s butler, Jean-Baptiste Cipriani. Napoleon, they claim, would then rest beneath a slab in Westminster Abbey as a trophy for the English monarch.

After all, and this is a historical fact, Napoleon’s funeral carriage, built to transport his body to its burial site, was indeed sent to England. This carriage, acquired by Sir Hudson Lowe, the British governor of Saint Helena during Napoleon’s captivity, was brought to England in 1828 to become part of King George IV’s collection of trophies. From there, it’s not a far leap to suggest that the carriage might not have been empty. In 1858, Queen Victoria offered the carriage to Napoleon III, and it was later exhibited at Les Invalides in Paris before being transferred to the Musée des Voitures at Malmaison.

| Inconsistencies in the Descriptions

Size and Appearance: During the autopsy on Saint Helena, Napoleon’s height was estimated at around 1.69 meters, but contemporary accounts describe a body that appeared noticeably shorter. Uniform and Medals: The clothing found on the body during the exhumation largely matched the 1821 description of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard Chasseur uniform, including a green overcoat, white vest and trousers, boots, and the Legion of Honour ribbon. However, some details were missing or differed, particularly the stockings.

According to French historian Bruno Roy-Henry, author of The Enigma of the Exhumed from Saint Helena, Napoleon’s remains do not rest at Les Invalides. In 1821, the tin coffin was enclosed within a simple wooden box, which was later replaced with a mahogany coffin in 1840.

Roy-Henry also highlights discrepancies in the measurements of the outer coffin compared to the Emperor’s funeral carriage, as well as differences in decorations, the disappearance of silk stockings, and the absence of spurs.

After a journey of several weeks, La Belle Poule arrived in Cherbourg on 30 November 1840, and the remains were transported to Paris via the Seine.

Grand national funerals were held on 15 December 1840, as the procession crossed the French capital, with huge crowds lining the route. The event concluded with an official ceremony at Les Invalides, where Napoleon now rests in a monumental sarcophagus weighing several tons, designed by Louis Visconti, beneath the dome of Les Invalides.

The return of Napoleon’s remains marked a turning point in how he was perceived, transforming him from a controversial conqueror into a near-sacred figure of national heritage.

Various claims and conspiracy theories surrounding Napoleon’s remains continue to circulate. Some even suggest that Napoleon survived Saint Helena and lived under another identity, which would explain the alleged replacement of his body.

It should be noted, however, that most historians reject these hypotheses, considering them to lack solid evidence. Historical documents, testimonies, and the objects found on the exhumed body, they argue, confirm that it is indeed Napoleon.

| The Absence of DNA Tests

There is no doubt that only a DNA test could definitively resolve the historical controversies surrounding Napoleon’s remains.

Despite scientific advancements, modern French authorities have never authorised a DNA sample to be taken from Napoleon’s remains for comparison with those of his relatives, such as his son, the Duke of Reichstadt, who is buried in Vienna. This reluctance has fuelled suspicions of a deliberate refusal to uncover the truth.

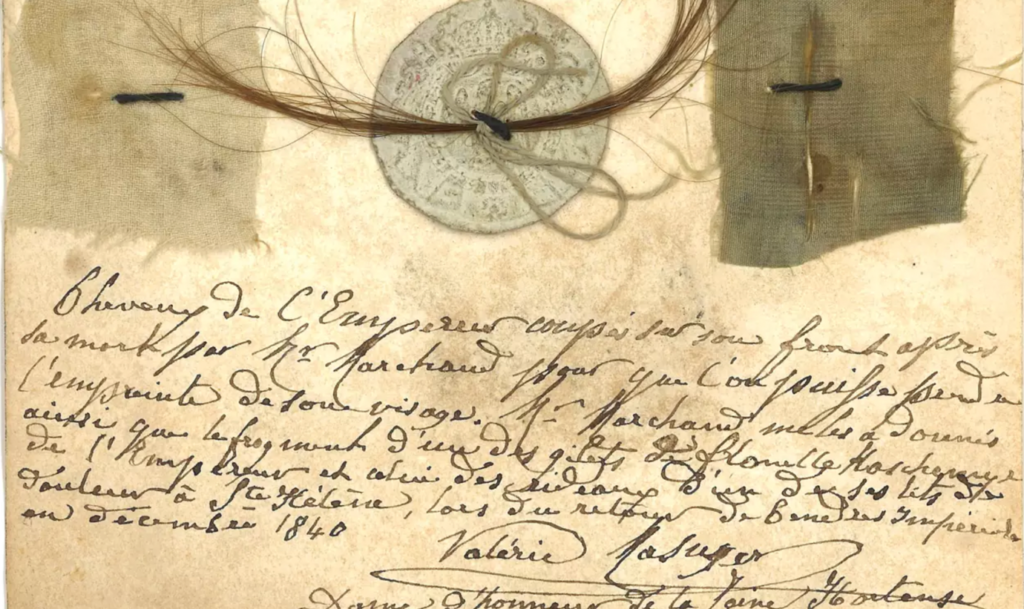

Scientists could analyse hair samples of the Emperor, which, according to writer Roy-Henry, were taken from Napoleon’s body during the return of his remains from Saint Helena in 1840 by Lieutenant Edmond de Bovis. Bovis entrusted these samples to a philosophy professor from Besançon, who later donated them to the city around 1900.

Another method to identify Napoleon’s remains would be to extract DNA from a death mask of Napoleon, a wax casting made from his face after his death. This mask, which contained beard hairs that were analysed, served as the model for the official death mask now housed at Les Invalides.

However, this approach would require verification of the authenticity of these objects, as many forgers have sought to create counterfeit items linked to the Napoleonic era for lucrative profit. DNA analysis of Napoleon Bonaparte’s remains would be a complex undertaking, requiring advanced genetic techniques and specific precautions due to the state of preservation and the historical context. Several key steps would be necessary to conduct such an analysis.

First, it would be necessary to open the tomb where Napoleon rests, but this presents significant ethical, legal, and practical challenges.

Another critical step would be obtaining legal and ethical approval to perform DNA testing on the remains. Given the Emperor’s historical significance, access to his remains is tightly controlled, and special permissions would be required—particularly from French authorities, the institutions managing his tomb, and his descendants. To date, all such requests have been denied.

Napoleon’s remains have been exhumed several times, and their state of preservation may have degraded over time. A preliminary examination would determine whether the DNA is still sufficiently well-preserved to be extracted. Napoleon’s body, buried on Saint Helena and later transferred to Les Invalides, endured fluctuating humidity and temperatures that could have affected the quality of the DNA.

Once the body is examined, a DNA sample could be taken. This would generally involve extracting a small tissue sample, such as a portion of a tooth or bone fragment, or even hair if authentic Napoleon hair is available.

Once the sample is obtained, DNA extraction would begin. This process involves using chemicals and laboratory techniques to isolate the DNA from the collected cells. Often, methods of “repairing” the DNA are required, as it may be fragmented or damaged, especially after many decades or centuries of exposure.

Genetic analysis of the extracted DNA would allow for comparison with DNA samples from Napoleon’s direct descendants – if such samples are available – to confirm the identity of the remains.

If, following such an analysis, the results were to be negative and show that the remains at Les Invalides are not Napoleon’s, the consequences would be unimaginable. This would challenge the authenticity of the remains currently displayed at Les Invalides in Paris. Scientists would then have to determine whether the bones found are truly those of Napoleon or whether another body was misidentified.

Symbolically and culturally, the impact on Napoleon’s historical memory would create a crisis of trust in one of the most iconic figures in French history. It could spark a debate on heritage and how France commemorates Napoleon. French authorities might have to reconsider how they manage and preserve the historical sites associated with Napoleon and potentially review the conservation of the remains. This could disrupt both the perception of Napoleon and the way his legacy is commemorated. It is worth noting that Napoleon’s tomb attracts around 1.5 million visitors per year.

And that is indeed the crux of history: symbolically, but also politically, the death of a famous, powerful, often murderous, dictatorial figure signals the beginning of a new era. The undeniable truth of their physical death is a condition for the historical reality of their life. Whether viewed positively or negatively, this is irrelevant. History is written at the moment when the powerful one’s eyes close forever. It is as though this eternal absence of gaze is necessary for the population to pass historical judgment, finally freed from the omnipotent figure’s gaze… And the famous recovery by successors, descendants, or even opponents can then take place.

Napoleon was right: history is a lie agreed upon by everyone.