A mine-launching shell from the First World War pulled out of Lake Zurich © Stadtpolizei Zürich

Switzerland is famous for the beauty of its mountains and lakes. People travel from all over the world to see and to climb those mountains and to sail or swim in its pristine waters. Why on Earth would anyone think it was a good idea to pollute them with explosives and with weapons of various kinds? Well, it’s one way to get rid of them albeit not necessarily on a permanent basis. We’re not talking here about doing this a century or so ago, back in ancient history. No, the Swiss military continued to dump its ordnance in several famous lakes right up until the middle of the 20th century. It was done with typical Swiss precision and care, of course, with the sunken ordnance encased in more than two metres of fine sediments, which you might think would make everything safer, but in reality that sediment itself can be stirred up, causing it to shift and worsen visibility for divers as the waters get murkier and murkier. It still seems odd to have a great, even unique, asset like those lakes and to deliberately pollute them with things that, if not handled properly, could go “bang” rather suddenly. It would be a catastrophe but an avoidable one.

You may well wonder at this odd activity, especially now that there’s so much concern about possible pollution. After all, explosives contain chemicals and not very nice ones, so how does one deal with possible leaks and the resulting contamination? Strangely, although contamination stories have been continuing to make headlines, Switzerland continued to use its magnificent lakes as military garbage disposal facilities. It makes no sense, despite the fact that water pollution checks carried out in the summer of 2019 claimed they pose no hazard to holidaymakers or bathers. It’s believed that just in lakes Thun, Brienz and even Lake Lucerne there may remain some 12,000 tons of military munitions that were sunk there between 1918 and 1964.

It would not make good holiday advertising: “Come and swim in our beautiful lakes, go down and look closely at our tank shells and detonators, admire the workmanship and try not to set any off.” No, of course, no-one has tried to sell Swiss holidays in that way. I don’t think it would attract hordes of eager tourists. Getting poisoned with chemicals or blown up by disused ordnance lacks popular appeal, somehow. Now Switzerland’s Federal Armaments Office, known as Armasuisse, is trying to find ways to clear the lakes of things below the surface that are very clearly not fish. They were, not to put too fine a point on it, munitions, and they were buried at a depth of between 150 and 220 metres below the surface. Hopefully that’s deep enough not to pose too much of a risk to little Pierre when he’s paddling with his bucket and spade, although it would very clearly be much better if they weren’t there at all. That’s why Armasuisse has been appealing for ideas and plans to get rid it of it all. In fact, the Swiss launched a competition (now closed to new entries), that was primarily aimed at academia and industry. It was not one that was ever likely to attract the local angling club. In any case, the Swiss Lakes’ native species of aquatic life, such as perch, fera or the Arctic char are becoming rarer. It’s all because of Arctic warming, of course, caused by the climate change in which US President Donald Trump doesn’t believe. Some professional fishermen are beginning to lose their jobs, especially those who relied on supplying important local restaurants with rare treats. At least this is making them all even rarer, so presumably it will put up the value of any that remain. Don’t forget to avoid those made of metal and possessing fins or propellors. They may be more than they seem.

As for the ways to track them – remember, they were buried with the aim of permanence – there are several possible methods, but none are simple. After all, although a vicious trout might bite you, an ordnance shell might blow you to smithereens. Your only compensation then would be the knowledge that your scattered and tattered parts would be providing food for the denizens of the deep. Or, since we’re talking of lakes, rather than oceans, denizens of the not-very-deep.

But to look at this issue seriously, we have to remember that a variety of rarely required tools may be needed to help locate the sunken armaments. Once under the water, things tend to migrate through the natural action of tides and water movement. I lost my much-loved wedding ring in the sea off the South of France many years ago and never recovered it. Some people have suggested magnets to help locate the displaced weaponry but that wouldn’t work if the metal used for construction was copper, brass or aluminium. After all, the people who designed and built these weapons didn’t want other people to detect them, even if they never expected them to end up at the bottom of a lake. What’s more, nobody with any sense would look for exploding armaments by poking through the sand and the silt with sticks, especially not metal ones (unless the searcher is feeling especially suicidal). However, the arms’ composition does make it somewhat difficult to trace them using conventional methods. Another problem is that the water tends to be cloudy, restricting visibility for divers.

Still, Switzerland has previous experience of having to move armaments under difficult circumstances. In 2020, the Swiss authorities reported that they would have to move some 3,500 tonnes of explosives that were, at that time, stored in a depot not far from the village of Mitholz, a pretty and typically Swiss village of sloping roofs and Christmas card appearance in the canton of Bern and with 170 residents in 2020. It’s also situated on the popular Lötschberg railway line. Back in 1947, an arms storage depot there containing some 3,000 tonnes of explosives exploded, killing nine people, so when a safety survey in 2018 decided the depot was still unsafe and therefore that it could explode again, it was decided that the entire village should be evacuated for a major cleanup. The plan is to order the evacuation for 2030 with the entire operation lasting for ten years, during which the residents will be relocated to somewhere that’s (hopefully) safer. That is a seriously major operation that’s unlikely to go down well with the residents, even if it means they’re less likely to be blown up.

The Swiss military had become accustomed to disposing of unwanted munitions by dumping them in water, where it was thought they’d be safe. But even allowing for the relative unlikelihood of an underwater explosion, there remains the risk of polluting the water with chemicals leaking out. Missiles and bombs contain quite a few, of course, and it’s thought likely that they could harm wildlife and plants, as well as posing a danger to humans. The Swiss government has issued statements to the effect that there is very little cause for concern, saying that they regularly monitor the situation and have found no sign of danger. They said in a statement that there is no immediate cause for environmental concern and that their research “currently shows no negative effects from the dumped munitions.” Now I would never accuse the Swiss authorities of dishonesty, but I can’t resist the thought that “they would say that, wouldn’t they”.

As for the munitions themselves, they are submerged at a variety of depths, with some as deep as 220 metres and others at a relatively shallow 6 metres. Officials in the past had assumed that the water would absorb any blasts. Now, they’re not so sure. Switzerland as a whole has been a neutral country since 1815, so it never plays a part in armed combat elsewhere, nor is it a part of any military alliances, not providing military assistance to any other country (including Ukraine). It’s hardly surprising that the Swiss would like to remove their sunken munitions, but moving them can be a pretty hazardous activity, too. After all, moving them could cause some of them to explode unexpectedly. They could also deteriorate or even disintegrate during removal, releasing some very nasty chemicals in the process. According to Mike Sainsbury, managing director of Zentica, a company specialising in dealing with unexploded ordnance, “it would be a painstaking process”. One would certainly hope so!

There have been several proposals put forward to the Federal Armament Office for ways to remove all these devices, which vary in size from 4 millimetres to 20 centimetres and in weight from 4 grammes to 50 kilos. Getting rid of them all won’t be easy, nor cheap. Removing them, according to Switzerland’s Federal Office for the Environment, is likely to cost several hundred million francs. We are left to wonder what on Earth persuaded the Swiss authorities of the time to dump their unwanted armaments in such a seemingly slipshod way. At least they’re not nukes, I suppose. Perhaps we should be grateful. Even so, as I mentioned earlier, in the years from 1918 to 1964, the army dumped a very large volume of unused military materiel into various Swiss lakes – especially lakes Thun, Lucerne and Brienz. It was certainly never a way to attract tourists, who generally don’t like the thought of being blown up, especially when they’re on holiday.

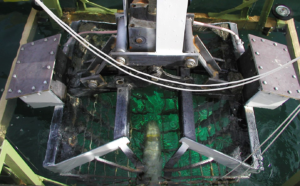

It’s quite a big issue in Switzerland, despite government-level assurances that the ordnance is safe. We have to remember that Switzerland, apart from being a “neutral” country is so opposed to armaments that it refused to send any of its arms to Ukraine. I can’t help wondering how many people have been made ill by eating too much Swiss chocolate. It is very lovely stuff, after all. As for the armaments dumped in Swiss lakes, there have been some fairly silly suggestions put forward by the public. One caught my eye: why not empty all the lakes, clean them up and then fill them up again. I presume the person putting forward that idea had not considered the actual scale of such an operation. Getting to the moon might be easier and cheaper. Still, it shows that the public are putting their diverse minds to the issue. Other suggestions include the use of “mining magnets” (which wouldn’t work on copper, brass or aluminium, of course). Then there’s the proposal to use “mechanical grabs”, although I suspect there would not be a great rush to be the driver. Or how about what was described as a “crawler”, which rather resembles an underwater version of a kind of bomb disposal robot. Another proposal is for a kind of moving box, presumably remote controlled, that would gather up the ordnance along with quite a lot of the surrounding lake sediment. Supposing one of these bizarre suggestions were to work, there remains the question of where to store the resulting heap of old ammunition, some of it presumably still live. Oh, and just in case the possuibility of pollution bothers you, a government report released in 2020 said there would be “negative impact of submerged munitions on water quality” That’s nice to know.

But the problems rumble on, whether the issue is anything to worry about or not. For a start, there are some 4,500 tonnes at the bottom of Lake Neuchâtel, thanks to a nearby army shooting range. The Swiss really scattered their armaments about, didn’t they?

Elodie Charrière, an environmental historian at the University of Geneva’s Institute for Environmental Sciences, has written a book about all those munitions dumped not only in Swiss lakes but also in French ones. She recently said that she was not surprised by the recent call for disposal ideas. After years of regular analysis of the issue by military authorities, she told SW1, an information channel, it’s “logical” that they now consider how to clear it up, even if this might sound contradictory, given that no actual salvage operation is so far planned (as far as we know).

Meanwhile, according to Swiss official sources, lake munitions disposal sites are classified as “permanent waste storage sites”, Charrière says. In fact, the ordinance doesn’t oblige authorities to clean up the lakes as long as they are not deemed contaminated. A lake full of things that could blow up one day apparently doesn’t count as hazardous in environmental terms. I bet all this publicity is doing wonders for the Swiss tourism industry. Come to the Swiss lakes – really make your holiday go with a bang!

The actual ordnance hidden down there is varied and some of it is quite old. I would have considered such aged explosive weapons to remain increasingly dangerous for decades to come. They include such delights as old Second World War bombs, grenades and various other explosive devices currently lying dormant (hopefully) at the bottom of Switzerland’s picturesque lakes or buried at the feet of its equally picturesque mountains. In any case, they are posing quite a headache for the Swiss authorities, who simply don’t know how to get rid of them safely.

It takes us back seventy years to the town of Kandersteg in the Burmese Alps, when 7,000 tonnes of high explosives went off, killing nine people. That, you may recall from earlier in this article, was in the town of Mitholz, where the railway station and quite a lot of homes were also destroyed.

Today, the defence ministry says the risk of a second explosion has been underestimated for decades. It has now become “unacceptable” and “total evacuation” is the best solution. As you already know, that is exactly what is going to happen, despite apparently rendering quite a few people homeless for a decade. Still, it’s better than another deadly explosion. In the case of Mitholz, the blast came at the end of the Second World War, when the town (village?) found itself stuck with a massive stock of unused weapons and ammunition. The dangers of hosting such a stockpile were exposed in 1946, when there was a huge explosion at a nearby fort at Dailly in the Canton Valais, which killed ten people. Mitholz blew up the following year and there was a third blast at a depot in Göschenen in 1948. The idea of making the ageing ordnance safe by sinking it in a lake caught on, and that’s what happened.

Now, of course, we’re all rather more concerned about safety and the environment. With the war newly ended people tended not to think far ahead. Today it’s different. How exactly we confront and deal with the issue has yet to be decided, but at last something is going to be done. We just have to hope that whatever is done can be dome without causing further explosions. Maybe (It’s a big ‘maybe’) we’ll all have learned not to just leaves piles of deadly munitions lying about. Maybe we’ll think seriously about how best to disposer of them safely. Knowing human kind, however, I remain largely unconvinced. Still, Switzerland is still a beautiful place with wonderful scenery, great skiing (if you enjoy such things), excellent chocolate and other luxurious foodstuffs: a great place for a holiday, in fact. Just be careful where you walk (or swim).