Cannabis is Europe’s most commonly used illicit drug. It is estimated that at least one in every eight young adults (aged 15–34 years) used cannabis in the last year across the European Union. At the national level, these rates range from less than 1 % to over 20 % of young adults. The most recent data provided by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), suggest that 1 % of the adult population (aged 15‐64 years) of the European Union and Norway, or about 3 million individuals, are smoking cannabis on a daily or near‐daily basis. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) is the central source and confirmed authority on drug‐related issues in Europe. For over 20 years, it has been collecting, analysing and disseminating scientifically sound information on drugs and drug addiction and their consequences, providing its audiences with an evidence‐based picture of the drug phenomenon at European level.

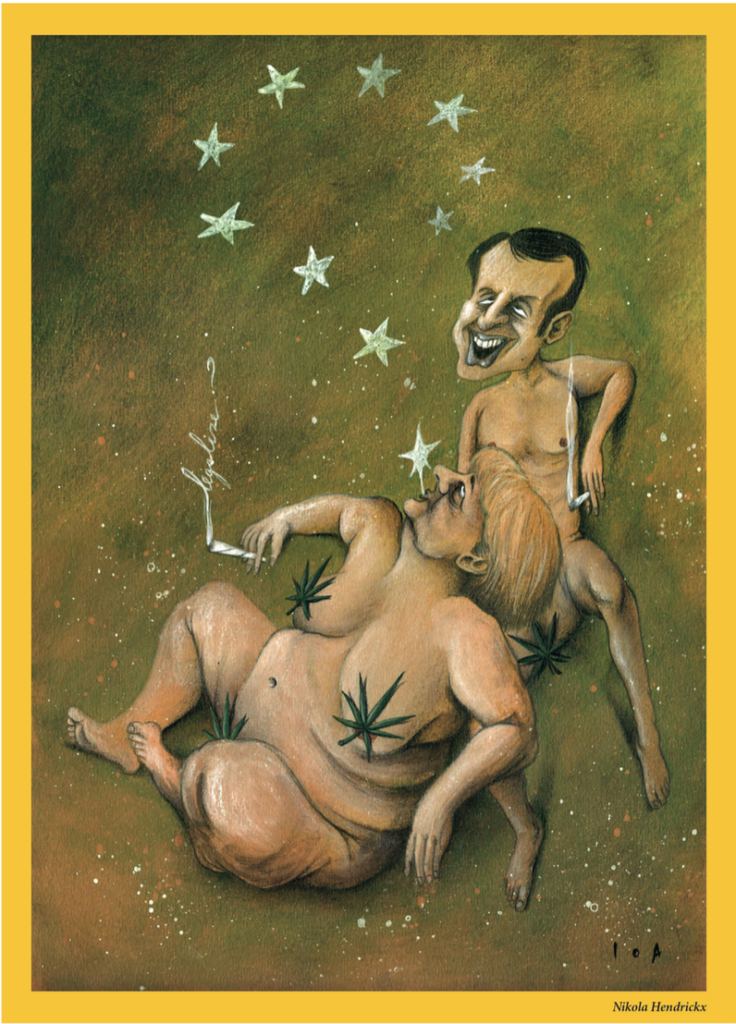

A renewed debate about the laws prohibiting or permitting cannabis use and supply around the world has been fuelled by the legalisation of supply and use of cannabis for ‘recreational’ purposes in some US states and Uruguay since 2012.

Proposals to legalise the drug have raised concerns they may lead to increases in cannabis use and related harms, and questions about the ways in which cannabis for non‐medical purposes could be regulated to mitigate these concerns.

Throughout Europe there is media and public discourse on the issue of changing cannabis laws. However, national administrations are concerned about the public health impact of cannabis use and generally oppose the decriminalisation or legalisation of cannabis for recreational use.

Nonetheless, cannabis laws and the medical and scientific research that informs policy‐making can be regarded as entering a period of change, the direction of which is still unclear.

LAWS AND ASSOCIATED GUIDELINES

There is little harmonisation among EU Member States in the laws penalising unauthorised cannabis use or supply. Some countries legally treat cannabis like other drugs; in others, penalties vary according to the drug or offence involved.

Evidence suggests that police tend to register cannabis use offences, rather than overlooking them as ‘minor’. In a few countries there can be a rehabilitative response such as counselling or treatment. While all countries in Europe treat possession for personal use as an offence, over one third of countries do not allow prison as a penalty in certain circumstances; of the remainder, many have lower‐level guidance advising against prison for that offence. Since 2000, the trend is to reduce the maximum penalty for use‐ related offences. The best available evidence does not show a clear or consistent effect of penalty changes on use rates.

Several proposals for full legalisation have been presented to

parliaments in the last few years, usually by opposition parties,

but most have already been rejected.

No national government in Europe is in favour of legalisation.

LEGALISING MEDICAL CANNABIS

International law does not prevent cannabis, or cannabis‐based products, being used as a medicine to treat defined indications. According to the UN conventions, the drugs under international control should be limited to ‘medical and scientific purposes’. Article 28 of the 1961 Convention describes a system of controls required if a country decides to permit the cultivation of cannabis that is not for industrial or horticultural purposes, while the 1971 Convention controls THC, the principal psychoactive constituent of cannabis.

WHY COUNTRIES SHOULD CONTROL CANNABIS

To understand today’s cannabis control laws, we must look at the history of international drug law, which binds signatory countries. Cannabis was first placed under international control by the Second Opium Convention of 1925 (League of Nations, 1925).

In Article 1, cannabis was referred to as ‘Indian hemp’, which covered only the dried or fruiting tops of the pistillate (female) plant because these were considered to be particularly rich in the pharmaceutically strong active resin.

The 1925 Convention banned the export of cannabis resin to countries that prohibited its use and required domestic controls, such as penalties for unauthorised possession of cannabis extract and tincture.

The convention established that any breaches of national laws

should be punished by ‘adequate’ penalties.

The international drug control system has evolved since then, and

currently three United Nations conventions describe the basic

framework for controlling the production, trade and possession

of over 240 psychoactive substances (most of which have a

recognised medical use).

These treaties, which have been signed by all EU Member States, classify narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances according to their danger to health, risk of abuse and therapeutic value.

HARMONISING EU LAWS

It is not easy to discern a common approach to the legislation surrounding cannabis across these countries. Many countries differentiate the legislation and penalties around cannabis sale and use, but in different ways.

Several countries treat all illicit drugs the same in the laws, others

define cannabis offences as a less serious legal matter, and a few

prescribe more severe penalties for cannabis offences.

Despite differences in formal legal sanctions, in most EU countries

the actual penalties for possession, use and supply of cannabis are

often less severe than those for other illicit substances.

Where countries have sought to divert cannabis users into treatment, it is not evident that this approach has received widespread support, with legislative initiatives being designed and implemented with varying degrees of enthusiasm.

It is not clear how much this is based on a desire to prioritise a

punitive approach or a lack of confidence in the effectiveness of

more rehabilitative responses.

Over the last 20 years, at least 15 European countries have made

changes to their legislation affecting penalties for cannabis users,

though there has been little rigorous scientific evaluation of these.

Use rates may be affected by other factors, such as anti‐smoking

policies, and other environmental prevention strategies may also

be playing a role.

This is a time of mounting public debate about cannabis policy. Advocates for change claim that cannabis is less harmful than other drugs but European statistics show the increasing potency of illicit cannabis and the increasing number of people seeking treatment for their cannabis consumption.

In order to avoid all excesses and to prevent situations where loopholes and differing legislations may allow dealers, as well as users to obtain illicit substances, it is time European countries effectively adapted their laws and implemented a common legislation.

The Editor-in-Chief

Trajan Dereville