© Live to Love International

Back in the early 1970s there was a craze for martial arts movies, such as The Way of the Dragon in 1972 and Enter the Dragon in 1973, both starring the Hong Kong American, Bruce Lee. His uniquely flexible way of fighting won him a massive legion of fans, spellbound by his acrobatic style. It encouraged lots of people – especially young men – to try to study martial arts, although most found that the strict discipline required gave way when the prospect of a glass of beer offered a tempting alternative. Another great martial arts star was Jackie Chan, whose kung fu moves, although equally athletic and acrobatic, were tinged with humour. Chan became a pro-Communist politician in 2013 and, at the age of 68, now sits in the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. Bruce Lee died in 1973 at the age of just 32.

Martial arts involving the unarmed style involving fists and feet were not invented by the Hong Kong film companies, of course. There have been a very great number of martial arts movies since then, including some involving a female protagonist. ‘Kill Bill’ and its sequel spring to mind. Even so, the early 1970s craze seems to have come to an end.

Kung Fu is a style of combat that was employed by members of the Yihetuan Movement, an anti-Christian, anti-colonial uprising of a group calling itself ‘The Militia United in Righteousness’. Their style was characterised by the British as “Chinese Boxing”, and their understandable attempt between 1899 and 1901 to get rid of the British became known as the Boxer Rebellion. There was also a TV series called Kung Fu about a Shaolin monk seeking his brother through the Wild West armed only with his martial arts skills, with David Carradine in the part of the monk. The series showed frequent flash-backs to his childhood in the monastery, where his blind ‘master’ called him ‘Grasshopper’, which is strange: Buddhist novices are nothing like those notorious plant-eating members of the suborder caelifera. It could be dangerous to call a child ‘grasshopper’, too, in case it incites various birds, frogs and snakes to eat them, believing them to be rich in vitamins A and B, calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese and potassium, as real grasshoppers are. They’re also low in cholesterol, although you may not fancy trying one as a healthy meat alternative. I don’t. In the TV series, I recall, there were at least two big choreographed fights in each episode, plus occasional scuffles and other examples of the hero’s skills. I hear it has recently been remade by Warner Brothers, who also made the original, this time setting it in the present day. As for Kung Fu, the first word, Kung (more accurately pronounced as “gong”) can mean hard or skilful work, while “Fu” means time spent, so together they mean time spent doing something difficult.

It established the idea that this particular style of unarmed combat had religious connections, although it’s said by some to have originated as a set of exercises based on animal movements and aimed at improving physical fitness.

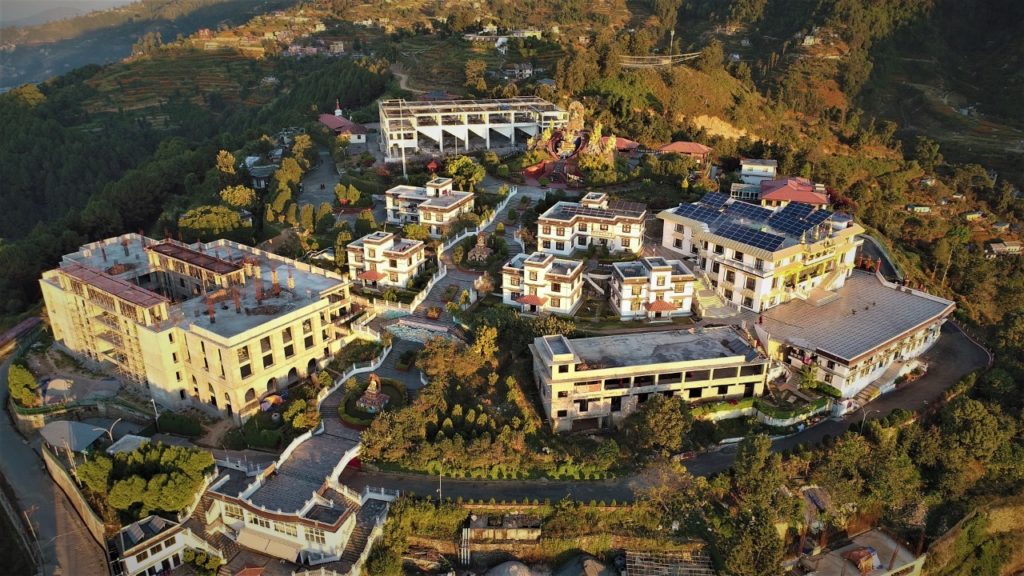

It is now closely linked in the public mind with the Shaolin Temple in China, whose monks are said to be brilliant exponents of Kung Fu, using its exercises mainly to sharpen their minds and to aid their concentration, as Buddhist monasticism demands. The Buddha, after all, preached peace, not kicking people. The Kung Fu nuns of the Drukpa order, mainly based at the Druk Amitabha Mountain Nunnery in Nepal, located in the hills overlooking Kathmandu, follow this ancient tradition and have been honoured for their achievements with the International Women’s Day Award, in a ceremony held at Delhi’s Stein Auditorium. The award recognises their contribution to the empowerment of women, disaster relief, environmental improvement and for breaking societal barriers. Looking at them in their Buddhist nuns’ robes, you would be convinced that they could break anything, if they chose to! It’s certainly not the first award they have received, nor is it likely to be their last. In 2021, they were runners-up for the Václav Havel award and their achievements were recognised in a joint statement by the Council of Europe, the Václav Havel Library and the Charta 77 Foundation. “Inside the nunnery in Nepal we are about 300, but altogether there are about 800 nuns,” Jigme Ghamo told me. “It’s a big group, which is spread in two parts of India, mostly in the northern part.” Jigme Ghamo and her fellow-nun, Jigme Konchok, agreed to meet me by Zoom link to talk about their work and their lives, which sound far from easy.

Not all of the 800 have begun kung fu training but there is a waiting list of those wishing to do so.

NEVER BE AFRAID

All the Drukpa nuns share the first name ‘Jigme’ and it’s a highly appropriate title for them: in Nepalese it means ‘fear-not’ or ‘fearless’.

Drukpa, on the other hand, means ‘dragon’. But however devout the nuns may be, they know there is much more to life than contemplation, important though that is. Each nun has her own mantra to chant to herself and to think deeply about. “Out in the world, sitting on a mat and meditating doesn’t help that much,” Jigme Ghamo conceded, “so if we want to go out in the world and help people, we have to be physically very fit and mentally very strong to understand the problem and to solve it, so I think kung fu has helped us in that way a lot.” But kung fu, for the nuns, is much more than just a means of energetic contemplation. “Yes, we have learned a lot of self-defence techniques also, but luckily we never had to fight someone off in real life.” She smiles at the thought of it; she has never had to and is relieved at that, but there is no doubt in her mind that she could.

“The nuns practise their kung fu for two hours every morning,” Jigme Ghamo said, “and the day starts at 3 in the morning with our own personal meditation, then we have English classes, then we have Tibetan classes. We have drum classes, we have music classes…we have lots of classes, but what is compulsory for all are the English classes, because if you are out in the world you have to know English, so everyone tries to learn it, and also Tibetan because everything we learn is in Tibetan.”

It sounds like a breath-taking day of endless study, but Ghamo assures me that other classes (yes, there are more) are optional. “If you want to learn, if you have an interest in music or if you have an interest in drums, it’s up to you, if you want to study it.” “It’s really fulfilling work,” says Jigme Konchok with a big smile, “and for several years we have not wanted to do anything else.” It’s not all study and exercises, however; there is often much, much harder work to do. For instance, they went on a 5,200-kilometre bicycle ride, which they called the “Bicycle Yatra for Peace”, riding from Nepal to Ladakh in India, over the course of three months, stopping along the way at literally hundreds of villages to educate the locals about environmental matters and to speak out against human trafficking, which still goes on there. The Yatra is now an annual event, with nuns encouraging others to help them gather up the garbage left in streams, rivers, fields and along roadsides. They provide a real rôle model for local people, too, refusing to be evacuated after the disastrous Himalayan earthquake of 2015 (magnitude 7.9) in order to deliver critical aid and supplies to neglected regions. “It is tough,” admits Jigme Konchok, “and really hard.”

They soon realised that the earthquake had resulted in more human trafficking, especially of young girls, as families, broken up and with many members killed, had taken to selling off their most financially valuable members, invariably young women, in a massive trafficking exercise. The nuns consistently campaign against trafficking, which has earned them enemies amongst those who make a disgusting living from the trade in human bodies. The nuns preach the evil of trafficking and try to equip young women and girls with the tools needed to resist the traffickers, by training them in martial arts and encouraging them to speak out about abuse. A group of them even travelled to New York to speak at the United Nationals General Assembly about the effects of the earthquake and their own battle against human trafficking. Their monastery and living accommodation had been severely damaged in the earthquake, too, leaving them more exposed to the wild natural elements of the area, but afterwards, each morning after they had finished their prayers and said their mantras, the nuns headed out to the nearby villages to help clear away the rubble and assist in the construction of new roads and pathways.

They also helped retrieve household goods buried under the rubble and to assemble and erect prefabricated community halls. One of the nuns, Jigme Jamyang Sherab, told journalists that the nuns’ priority had been to provide buildings to shelter the villagers before the onset of the monsoon season. Her parents asked her to leave the nunnery and go home to Himachal Pradesh in India, but she told them she would prefer to stay “to help recouping survivors who have witnessed the large-scale death and destruction.” Meanwhile, the nuns erected tents in the nunnery grounds because the more solid walls that offered better protection had developed worsening cracks.

Getting around such mountainous terrain on bicycles is a tribute to the women’s kung fu-based fitness, while they also run free health clinics, where they have helped to restore sight to more than 1,500 Himalayan people. Amazingly, that’s not all: they respond to emergency calls to rescue animals in distress and have collected for disposal thousands of kilos of plastic waste, which had been littering the fields and roadsides. The nuns do have enemies, Jigme Konchok admitted; not everyone approves of women having such high status and respect, but so far this has not led to them being forced to defend themselves. “We hope one day we can use our kung fu,” she told me, with what I can only describe as a mischievous smile, “but so far this hasn’t happened. But we are confident we could if we had to, as we travel around the villages. Some people speak to us really rudely. But we stay confident.” Having seen videos of the nuns at practice, I’m not surprised they’re confident. I’m surprised anyone has the temerity to be rude to them, however.

IT PAYS TO BE TOUGH

Their training programme is not something anyone would take on lightly. “A very normal day of our lives starts at 3 in the morning,” Ghamo explained, “We do our personal meditation until 5. Then from 5 to 6 we have our morning session in the temple. Then at 8 we eat our breakfast and after that, from 9 until 10, we do our housework and cleaning and then at 10 everyone goes to their different classes, whatever they like. They all know, at 10 they do what they choose.” It was clear that they had to choose something worthwhile to study, however; sitting chatting over coffee with a friend clearly isn’t an option. “At 12 o’clock there is a class,” she continued, “then we have lunch. (They are all vegetarian, of course) After lunch we are free until 2, then we do meditation and housework. We are free then to do what we like. Then we have classes until 4, after 4 we have our evening tea. We don’t have dinner. After that we have free time to sit, to do more housework, more meditation. At 6 we have our evening session in the temple. In summer, we do kung fu at night, from 8 to 10, and in winter we do kung fu in the morning. So it depends on the weather.” Both nuns laughed at this point. They have obviously had to explain their routine many times and to many people, most of whom, I suspect, were as amazed as I was.

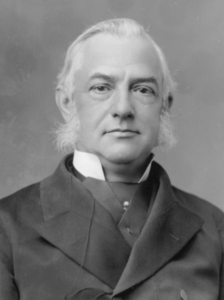

The contemplative life seems to involve a lot of vigorous, perhaps sometimes painful, activity. It’s not something I could undertake. But Buddhism is supposed to depend on the principle of self-sacrifice. According to Doctor Max Müller, the orientalist and first Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford University, in his book ‘Sanskrit Literature’, Buddha encouraged people to take responsibility for other people’s problems, in a way that may be familiar from other world religions. “Let all the sins that were in the world fall on me,” Buddha is claimed, in Müller’s book ‘Sanskrit Literature’, to have said, “that the world may be delivered.”

That passage by Müller is also quoted in Edward Carpenter’s 1920 book, ‘Pagan and Christian Creeds: Their Origin and Meaning’, a copy of which, ironically, was given to me as a child by my godfather. The oddness of such a gift from such a relative did not escape him, even though he had made many annotations in the text to soften its otherwise atheistic tone. There is more in a similar vein in the Metta Sutta, a Buddhist text intended to encourage kindliness towards others: “Let him cultivate boundless thoughts of loving kindness towards the whole world,” it reads, “above, below and all around, unobstructed, free from hatred and enmity. May all beings be well and safe, may their hearts rejoice. Just as a mother would protect her only child with her own life, even so, let him cultivate boundless thoughts of loving kindness towards all beings.” Such sentiments would certainly seem to guide the kung fu nuns

Their most recent award came from the Delhi Commission for Women, with the award itself being given out in front of a number of Delhi dignitaries, including the speaker of the Delhi Legislative Assembly, Ram Niwas Goel, and Deputy Speaker Rakhi Biria, with the chief guest, Chairperson Arvind Kejriwal presiding.

The Delhi Commission for Women established the International Women’s Day awards in 2016 as way of rewarding women and women’s groups that have been inspirational in helping the cause of women’ and girls’ rights. At the ceremony, Jigme Ghamo described the nuns’ activity as “breaking a centuries-long social order favouring men in leadership.” She then explained that: “The kung fu nuns are taking on kindness in its fiercest form – empowering themselves and others to serve the world.” She and fellow-nun Jigme Konchok told me the award was important to them because it raises their profile, which helps them in their work, but it’s not their first award and is very unlikely to be their last. “We are honoured to be recognised for our efforts,” she told the crowds at the ceremony, “and this award will help us spread our message of empowerment and further strengthen our mission to help women and girls to be their own heroes.” The nuns teach martial arts to promote self-defence to young girls within their communities, where reporting violence against women is rare. Sadly, it seems too many men still interpret their apparent lead rôle in traditional societies as a licence to use violence against women.

There have been other objections to the nuns’ allegedly “unfeminine” activities. “Sometimes older people will tell us we should just stay in the temple and read, or stay in the kitchen,” Jigme Konchok told the Matters India news website, when the nuns were finalists in March 2021 for the Václav Havel Human Rights Prize, which is awarded annually by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Another of the nuns, Jigme Chosdon, indicating their badly damaged kung fu practice room, said: “The earthquake shook the buildings but not our strength and energy,” going on explain: “It’s all due to intensive training of the martial art and meditation.” Maybe it will catch on further? One woman, having seen a report about the nuns’ martial arts regime on BBC Television, commented: “Apparently it helps them to concentrate better on their meditation and has also increased their confidence. Maybe we should all be taking it up?” Having seen the nuns, in their maroon garments and with almost shaven heads, it’s not easy to imagine them in a kitchen or sitting primly around a parlour somewhere, eating biscuits and sipping tea.

The nuns’ spiritual leader, the 12th Gyalwang Drukpa, is actively encouraging gender neutrality. The nuns themselves don’t need much encouraging. The Gyalwang Drukpa started teaching the nuns kung fu in 2008, after seeing Buddhist nuns in Vietnam doing it. He was impressed. “I became a nun when I was 12,” says Jigme Ghamo, “but we didn’t have kung fu then. That was in 2006. Kung fu was introduced in 2008, and at that stage it was only exercises, just basic exercises. Then in 2012 we started learning the martial art of kung fu.”

BEING READY FOR ANYTHING

When they are travelling round their vast and very mountainous territory, the nuns are not completely alone; it would be a dangerous place to have a fall, which is why they try to keep their burdens to a minimum. Jigme Ghamo again: “When we are on our bicycles, we only carry what is really necessary on our backs, but we hope in the future to carry more things. Now we only carry what is really necessary in our little bags. We have a vehicle for emergencies and three hundred nuns are at the ready. If anything happens on the way, if you fall down and get hurt and you need immediate emergency help, if we are in a village where we cannot get an ambulance, you cannot get to a hospital, so we have an emergency car with us all the time. Other than that, we are very self-sufficient. We have solar panels and solar lights and so on, so that it’s easier for us to carry on.” Buddhist orthodoxy holds that there are “Four Noble Truths”. This basically comes down to the following: “life is painful and frustrating”. That would seem to be self-evident; a glance at things around you and at the news channels is ample proof. Secondly, Buddhism says that suffering is caused by our strong attachment to what is familiar, “the known”. Thirdly, in Buddhism, pain and suffering can be brought to an end by getting rid of our expectations and attachments. It argues that we can still have meaningful relationships but without the sort of needy, clinging attachments that come from a fear of loss and of being left on our own. Finally, it says we should all engage in meditation, or the practice of mindfulness and awareness. That is why the nuns spend so much of each day in deep meditation.

One of the things upon which they must meditate is what Buddhists call the “noble eightfold path” to enlightenment: seeing things as they really are without passing judgement; working with pure intentions; speaking from the heart; surrendering a tendency to complicate things with our own expectations; do our best whatever life throws at us (“bloom where you’re planted”); do things the right way; be mindful of our tiniest thoughts, emotions and actions; discipline our minds in order to concentrate on the here and now, rather than on another time or place. The idea is to achieve “Nirvana, which is not what other faiths call “heaven” but is instead a state of mind free from suffering and having got rid of aggression, struggle and drama. You can see why Buddhism appealed to the hippies of the late 1960s. It was a break from their parents’ religious observations, an excuse not to get up early enough to go to church, mosque or synagogue on a day-off from school or work and it appeared to leave more room for ‘self-fulfilment’ (although few could have explained what that meant, beyond ‘please yourself’). It also didn’t require an attempt to explain where we all came from. Not all church officials of the Middle Ages were blind to the contradictions between doctrine and observation. Take the 14th century scholar, philosopher and mathematician Nicole Oresme, for instance. In one section of his famous book Livre du ciel et du monde (Book of the Heavens and Earth), book II, chapter 25, he examines whether the apparent diurnal motion of the heavens is due to the earth spinning on its axis, or the heavens moving around a stationary earth, as the church preferred. Oresme provides an excellent analysis of this problem. He concludes that, contrary to much church teaching,

“The primary argument is for the economy of motion: it is much less motion for earth to rotate than for the whole of the heavens to hurtle around the earth daily. Indeed, due to their vast circumference, the speed at which they would have to travel would be excessive.” Clever chap, Oresme; it’s been said that he considered that it was in the space beyond the part of the universe we can see that God was hiding. I wonder. Buddha didn’t seem to mind much either way and his modern followers are somewhat ambivalent about God. He is said to have followed the doctrine of Shunyata, which means ‘emptiness’. On God, he maintained ‘a noble silence’, apparently.

In any case, the whole debate, taken together with the hippy desire to ignore things one doesn’t like or in which one is not interested, is a universe away from the sometimes violent Christian sects, mainly in the American deep south, whose cries of “Deus Vult” were once used in the 12th century to rally potential fighters to the crusading cause of Pope Urban II. It means “God wills it” and it followed a sermon by Urban in which he urged people to lay down their work, leave their homes and families and go off, armed to “liberate” (defeat and occupy) the city of Jerusalem. As Dan Jones points out in his excellent book about the Middle Ages, Powers and Thrones, “Deus Vult has more recently been adopted as a watchword and a meme, notably by the alt-right, white supremacists and anti-Islamic terrorists,” adding the warning: “Be careful before shouting it in polite company.” Given the Crusaders’ attitude to those of other faiths and races, perhaps Urban II would have approved of its modern appropriation by violent extremists.

The nuns don’t have to worry about sword-wielding religious fanatics these days, but they still have to cope with the climate, which is very hot in summer and very cold in winter, when, as Jigme Konchok told me, “it’s very hard to take a bath.” Since it involves water from an ice run-off, I should imagine it is, but so, it seems, is a visit from their teacher. “He comes for a month or two every year,” says Jigme Ghamo. “That part is the hardest part because we have to train for ten hours every day. That’s ten hours every day for one to two months, because we have to learn a lot of things so that we can practise it the whole year. That time is very hard, because we still have to continue our normal practices and we have to follow the rules of the nunnery.” It’s a very far cry from ‘The Sound of Music’, isn’t it? But their faith is important to the nuns, even if it’s not what they are most famous for. “If I only talk about Buddhism,” Jigme Ghamo says, “If I only talk about my faith, if I only talk about what I want, you know, that doesn’t appeal to all kinds of audiences. For us, helping people is our religion. We do not bring our religion (religious faith, in other words) into any kind of work we do. In any kind of conversation we have outside our nunnery we do not bring up the subject of religion. As soon as somebody brings up the subject of religion there is sort of division: ‘you are a Buddhist’, or ‘you are a Muslim’, or ‘you are a Christian’, so there is a barrier. It builds a wall between us.” At first appearance, the kung fu nuns, with their severe haircuts, extreme fitness, adoption of kung fu fighting stances and nunnery robes would seem like unlikely adversaries for anyone who is ill-intentioned to choose to come up against.

FIGHTING THE DEMON

One enemy against whom even kung fu training provides few if any options for dealing with is the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the cause of COVID-19. It has provided extra challenges for the nuns to cope with, but you cannot defeat it with a fighting fan (a hard-edged fan used in some forms of kung fu) or a well-aimed flying kick. But Buddhists, through studying their scriptures, are used to coming up against Mara, the demon and “Lord of Death”, in some early Buddhist writings. He is said to have tried to tempt the young Siddhartha Gautama – the future Buddha – while he was meditating by presenting him with a stream of stunningly beautiful young women.

In some versions, they are Mara’s daughters. He is the equivalent of Satan, the Devil, Iblis or Lucifer in other faiths, who also try to lure the faith’s central figure away from the paths of righteousness. The “Lord of Death” seems an appropriate enemy for those fighting COVID-19, an enemy even the Kung Fu Nuns cannot defeat, although they are still doing their best. “We still found ways to help others,” Jigme Konchok tells me, “by taking supplies to the villages. Also the animals were not being fed, so we took food to them and looked after them.” If you want to use the Buddhist allusion, then at least Mara didn’t get everything his way.

Strangely, the Devil is often portrayed in religious works as a dragon and dragons were generally associated with evil in the West. Where I come from, in North East England, there is even the story of the Lambton Worm, a dragon-like creature that turned up to eat the locals because wicked Lord Lambton had failed to observe Sunday as a holy day and had gone fishing in the River Wear instead.

Unfortunately, he caught the Worm, which went on to terrorise the land around Penshaw Hill (around which the dragon, in some versions, was said to curl itself) until Lambton returned from the crusades to tackle it. Again, he broke his promise to a witch who had helped him to win and as a result the Lambton family was cursed, the men of the next nine generations not dying in their beds. That part of the story came true and even as recently as the 1970s, another Lord Lambton, Anthony, was embroiled in a scandal involving prostitutes and cannabis that ended his ministerial career in government, much to the delight of the tabloid newspapers of the time, several of which raked up the tale of the Lambton Worm to explain his downfall. There is still a hill at Fatfield, near Washington in County Durham (not the one in the District of Columbia, of course) known as ‘Dragon Hill’, claimed to have been the Worm’s favourite resting place (as distinct from Penshaw Hill). There is a popular and very funny music hall song from 1867 about the legend. However, in Far Eastern mythology, dragons are good, and the Kung Fu Nuns, of course, take their Drukpa name from a dragon. One assumes that the propitious dragon in this case was never thrown down a well nor did it impoverish a rich estate by drinking the milk of nine cows, as the Lambton Worm is supposed to have done.

The Kung Fu Nuns, of course, are associated only with good deeds, courage, fortitude and kindness. Whilst praising their selfless devotion to helping others, we must remember that they are, first and foremost, nuns, dedicated to the religious monastic life. They believe in Buddha and follow his teachings. As members of a religious order, they are what is called ‘bhikshu’ in the Dhammapada, the book supposedly of the Buddha’s sayings, translated by Doctor Max Müller. Chapter 25, verse 382, would seem to apply to the nuns, if we change the gender used in the reference: “He who, even as a young Bhikshu, applies himself to the doctrine of Buddha, brightens up this world, like the moon when free from clouds.” It would seem that the nuns do exactly that.