© EDM

Russia’s involvement in the Arctic region is deeply rooted, dating back centuries to the conquest of Siberia in the 16th century. Over the years, successive governments have strongly supported and promoted various activities in the region, focussing primarily on facilitating trade and the extraction of natural resources. Over the course of the 20th century, the discovery of oil and gas deposits in Siberia, both below and above the Arctic Circle, proved to be extremely lucrative. These resources not only brought wealth and foreign currency to the nation, but also contributed to domestic consumption, financed the Soviet military apparatus and served as the economic basis for the Soviet Union to pursue its foreign policy goals.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia’s involvement in the exploitation of Arctic resources gained considerable momentum. Oil and gas played a central role in revitalising the country’s economic situation in the early 2000s. This resurgence in economic stability played a crucial role in fuelling Vladimir Putin’s rise as Russia’s undisputed leader. It also enabled Russia to reclaim its position on the world stage as an ambitious superpower determined to regain its influence in Europe and assert its rightful place in the international system.

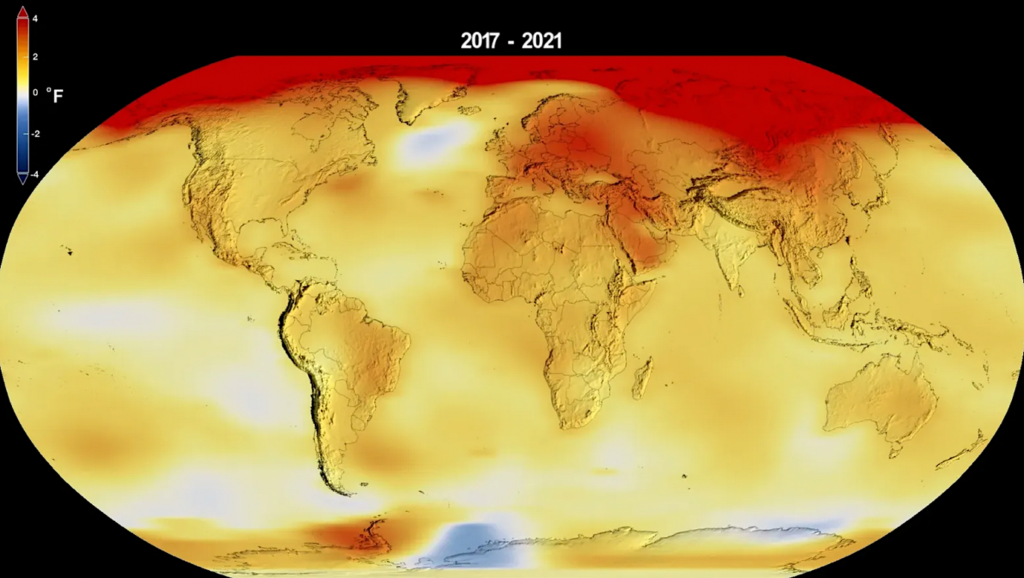

But there is one huge problem which, at the time, was not considered as part of the equation; global temperatures have risen by around 1.3°C above pre-industrial levels, and this increasing heat is unevenly distributed around the globe.

The Arctic, often referred to as the Earth’s freezer, is experiencing a rapid thaw due to the effects of climate change. Thermometers in the region are rising four times faster than in other parts of the world as the Arctic is increasingly exposed to intense solar radiation. This feverish warming is upsetting the delicate balance of the pole and triggering widespread ice loss with far-reaching consequences.

Be that as it may, Moscow is seeking to capitalise on the dwindling ice and exploit the thawing treasures, leading to tensions as rivals jostle for position in the newly navigable north. Economically, the melting of the permafrost favours opportunistic drilling for oil and other minerals, but threatens the way of life of the locals. Ecologically, reversing this frozen feedback loop, risks global destabilisation.

As the canary forewarned coal miners of the danger of carbon monoxide gas, the Arctic is the first to sound the alarm that the climate crisis is sparing no place in our shared, rapidly warming world.

Much has been said about how global warming may bring about more conflict, but to understand its roots and connections to climate change, we need to understand what is happening to Arctic Sea ice.

In recent decades, significant changes have taken place in the vast icy components of the Earth’s cryosphere. These components consist of frozen water reserves such as ice caps, glaciers, snow packs, permafrost and the Antarctic ice sheet. Analyses of satellite data show that the extent of Arctic sea ice in the summer months decreased by more than 10 per cent per decade from the late 1970s to the mid-2000s. If this pattern continues, the Arctic region could experience ice-free summers for the first time in the 21st century.

Russia’s extensive coastline within the Arctic Circle, which stretches over 24,000 kilometres, poses a major challenge. In the past, the sea ice acted as a robust natural defence, effectively keeping military ships and submarines at bay.

However, the decline in the extent of sea ice has led to less ice cover and even longer periods without ice. As a result, foreign reconnaissance vessels can now approach much closer and remain in the region for much longer, exceeding the level of proximity desired by Russia.

Mathieu Boulègue, a Senior Fellow with the Transatlantic Defense and Security Programme at the Centre for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) says: “If history has taught us anything about how Russia perceives these intrusions it’s that they need to limit the presence of foreign actors, and they do it the way Russia does it, which is to militarise the region to make sure that we don’t get too close. And by ‘we’ I mean the collective West, and now, NATO.”

Militarisation of the increasingly ice-free and exposed border began in earnest in the 2010s. However, relations threatened to freeze when Russia adopted a much more aggressive stance. Common interests in the once cooperative Arctic states of the polar region are fracturing, primarily due to Moscow’s provocative actions and policies, particularly its behaviour towards Ukraine since 2014 and continuing until the full-scale invasion of that country in February 2022.

| EMERGING FAULT LINES

Analysing contemporary Arctic geopolitics reveals the definition of intriguing new dividing lines. Where once coexistence prevailed throughout the region, Russia is increasingly isolated, while its adversaries are levelling up. With the expansion of the Atlantic Alliance through the accession of Finland and Sweden, the seven NATO states surrounding the Arctic Circle now form a solid united front, with Russia as the only outlier.

The once disparate, independent states have consolidated into a dynamic that essentially pits Russia against NATO. As the Kremlin displays more antagonism and the alliance tightens its ring around Russia’s northern borderlands, the long-standing cooperative dynamic is now giving way to the demarcation of clearly opposing camps. In the future, interactions are likely to polarise along this emerging divide between Russia and the rest of the world unless steps are taken to rediscover common interests and mitigate escalating tensions between the erstwhile partners along the circumpolar passage.

Russia’s growing militarisation in the Arctic is unmistakable. For years, a slow but steady process of regaining control over certain territories and consolidating its physical presence has been underway. Existing military facilities have been reinforced and new airstrips have been built to accommodate larger and heavier aircraft should the Kremlin deem their deployment necessary.

However, it’s important to distinguish between two facets of security in such an environment. ‘Soft security’ is primarily concerned with search and rescue operations and border protection, such as curbing illegal fishing or trafficking. In contrast, ‘hard security’ refers directly to military weapons and capabilities that can provide important information about the enemy.

As analyst Mathieu Boulègue points out, “A defensive system can literally be turned into an offensive one just by the flick of a switch. Russia may not be seeking to escalate the situation for no reason, but in planning for all contingencies including defensive maneuvers, it is also planning for war.”

As Russia stealthily expands its military capabilities in the Arctic, uncertainty about its strategic intentions inevitably grows – requiring vigilance from all parties to prevent unintended crises in this newly accessible but volatile region.

| THAWING PROFITS AND PERILS AS CHINA STEPS IN

After years of actively excluding China and other non-Arctic nations from the region, Russia’s attitude has notably shifted. Previously, Moscow denied Chinese scientists access for research and also declined to assist Beijing in building icebreakers or obtaining related technical infrastructure. While Russia once firmly rejected China’s involvement, recent developments suggest a change in approach. Given the setbacks related to the Ukraine campaign, Moscow seems to have eased its restrictive policy and is gradually permitting an expansion of Chinese presence and the transfer of capabilities rather than obstructing them.

This strategic adjustment signifies a significant geopolitical development and indicates Russia’s willingness to leverage Sino-Russian cooperation across the previously tightly controlled Arctic border. After years of defining China’s role in the polar region, Moscow’s removal of barriers signals increased PRC engagement and potential challenges for traditional regional players observing this adaptive diplomatic shift.

The burgeoning friendship between Russia and China has paradoxically been favoured not only by sanctions, but also by the effects of climate change, particularly melting sea ice. This ecological change has opened up a new trade route through the Russian Arctic, providing Russia with the opportunity to generate revenue and support its ongoing military activities despite the restrictions imposed by the sanctions.

Malte Humpert, is a senior fellow at the Arctic Institute in Washington DC, a think tank specialising in Arctic policies: “There is the shipping route that goes along Russia’s northern coastline, from Scandinavia in the west all the way to the Bering Strait, close to Alaska in the east. For transit shipping from Asia to Europe, this route is shorter by about 40% compared to transiting through the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal. While this route is not practicable in winter due to ice formations, it is clear for four or five months per year.”

But just to clarify this point, it should be noted that the volume of world trade that is handled via this route is still relatively low, although it is steadily increasing and has become a significant source of income for Russia which has the ability to collect fees and tolls from ships using this route.

According to Malte Humpert, the Arctic region overall accounts for around 20 per cent of Russia’s GDP. However, there is some disagreement over this claim; the United States argues that Russia does not have the right to charge tolls, and many countries have decided to boycott this trade route since the invasion of Ukraine. But there are exceptions to this boycott, notably China, which continues to trade via the Arctic route.

For China, the Arctic represents a strategic alternative to vital but vulnerable trade routes. Beijing is heavily dependent on chokepoints such as the Suez Canal and the Strait of Malacca, over which it has little control, and is aware of its vulnerability. Imagining the climatic conditions in a few decades, Chinese analysts foresee an even greater dilution of control.

As the earth continues to warm, more and more polar sea lanes will thaw, expanding shipping opportunities as ice sheets diminish. The melting of harbours holds hidden economic benefits for China’s long-term prospects. The harsh Arctic climes may be imposing now, but they offer potential answers to emerging geopolitical pressures on globalised supply chains and oil imports.

This is how Malte Humpert charaterises the relationship between Russia and China: “China is definitely a benefactor of the sanctions; they receive more and more oil from the Russian Arctic and they are receiving it at a discount. They are paying about US$ 6 less per barrel for Russian oil compared to Saudi oil. Russia has now replaced Saudi Arabia as the biggest provider of oil to China.

The melting ice in the Arctic has opened up new opportunities for Russia to explore and produce larger quantities of oil and gas than in the past. Russia is currently producing 40 per cent more oil in the Arctic than ten years ago. However, operating in the Arctic poses considerable challenges. The region is characterised by hostile conditions, including sub-zero temperatures, and is extremely isolated. In emergencies, it can take weeks or even months for help to arrive.

In addition, there is no existing infrastructure in the Arctic, so it has to be built from scratch, which makes operations in the Arctic a very costly endeavour. But as Malte Humpert explains, this is precisely where China once again comes into play: “China has invested heavily in those operations, including the liquefied natural gas project on the Yamal Peninsula situated in northwest Siberia. There is also the upcoming LNG 2 Project. But the irony here is that it took climate change to melt about 50 per cent of the ice, allowing more exploitation of oil and gas, causing more CO2 emissions! But for Russia, this really is a lifeblood.”

These new relations between Russia and China, two of the world’s superpowers, might be perceived by some as threatening, and certainly something the US and Europe will be watching closely, particularly in the Nordic countries, all members of NATO.

The Arctic-Atlantic Interconnection Zone, in which the five Nordic countries are located, serves as a vital link between the Arctic Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean and stretches from north to south. It is of strategic importance as it overlooks the eastern and western regions of the North American and European continents, respectively.

As the security of the United States is closely linked to this region, so it is seen as imperative for the US to prevent China from gaining a foothold or significant strength there.

However, China views the Nordic countries as the western terminus of its ‘Polar Silk Road’, a crucial component of China’s broader ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. Therefore, China has significant shipping, scientific and strategic interests in this region as the ‘Polar Silk Road’ is of immense importance to China’s endeavours to improve connectivity and promote trade between Asia and Europe.

| RISING TENSIONS

Whatever China’s and Russia’s aims may be, as technological progress enables more efficient resource extraction in the Arctic and climate change causes ice cover to shrink, competition for influence and control in the region intensifies. Advances in the exploitation of fisheries, rare earths, oil and gas are leading to a race for resources that threatens future clashes.

Even among allies, minor disputes over territorial boundaries and transit rights on newly navigable waters continue as the legal framework fails to keep pace. Meanwhile, the Arctic states are expanding their military infrastructure, such as bases and patrols, to secure the burgeoning resources and transit routes, increasing tensions.

The environmental changes that are restructuring the geopolitical equation are leading to unintended security consequences that are difficult to predict. As access to natural resources changes and dependencies deepen, old disagreements could escalate into major rifts without careful co-operation. And as the thaw opens up once-frozen borders, outside powers are sure to probe vulnerabilities and fuel geopolitical jockeying.

To further complicate the situation, Russia has called for restrictive measures along the shipping route, including requiring foreign warships to give advance notice and obtain Russian authorisation before passing through. These measures restrict international access to the sea route and pose a challenge to the principles of freedom of navigation laid down in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

There are no easy solutions to secure fair access and sustainable development in this time of change. Vigilance and compromise will be required from all sides to manage tensions and prevent the growing strategic pressures of a warming climate from boiling over into open geopolitical conflict in the increasingly contested Arctic domain.

Although there is no centralised governing body in the Arctic, there are several loosely cooperating organisations. Of these, the Arctic Council, based in Washington DC, and to which the eight Arctic states belong, has proved to be the most successful forum. The Council’s work focuses on environmental monitoring, supporting indigenous communities and coordinating emergency response. However, it does not deal with national security issues.

There are numerous complex problems in the region that have the potential to escalate into conflict. Even among the allied nations, there are minor disagreements over territorial claims and navigational rights. In addition, the expansion of military bases and deployments poses a challenge, as some Arctic nations view them as essential to securing their resources and logistics networks. These factors contribute to the complicated dynamics and potential tensions in the region.

| ENDANGERED FRONTLINE COMMUNITIES

Sensational headlines announcing a new cold war in the Arctic abound in international media. But analyst Mathieu Boulègue is more sceptical and believes that such declarations and analyses are too alarmist: “There are attention-grabbing headlines that should not be taken at face value. Cooperation remains, despite the current geopolitics when it comes to matters of, for instance, border management between Russia-Norway and Russia- Finland…when it comes to search and rescue operations at sea. In the same spirit, Mikhail Gorbachev made a famous speech in 1987 in which he said that geopolitics should be laid aside in the Arctic because of the nature of the environment. Because of the fragility of the environment.”

With his groundbreaking speech in Murmansk in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev presented a visionary foreign policy concept aimed at changing the economic, ecological and security policy dynamics in the strategic and sensitive Arctic Circle.

In his speech in the icy northern Russian port city, the last Soviet prime minister wanted to transform the polar region from its status as a Cold War military hotspot into an internationally recognised zone of peace and cooperation between the Arctic powers. Known as the ‘Murmansk Initiative’, Gorbachev strove for a co-operative approach to the new challenges in the Arctic.

But those days of cooperative management in the Arctic are long gone, as even the small risks of renewed superpower rivalry weigh heavily on the communities most affected by climate impacts. Without cross-border cooperation, it will become increasingly difficult to jointly address the melting sea ice, opening new shipping lanes and fears of associated militarisation in this sensitive area.

The inhabitants of the Arctic are facing increasing change as a warming world restructures the opportunities and threats on their doorstep. But geopolitical upheavals are now isolating Russia’s borders from collective efforts to mitigate climate change, jeopardising populations who rely on mitigating emissions as much as possible.

The only balm could be unprecedented global action to reverse the warming of the atmosphere and renew the retreating ice shelves – a multi-generational task that revitalises the solidarity of scientific collaboration in the fight against the climate crisis. But even stabilising temperatures may not be enough if disputes outweigh goodwill across the ice margins, which are fraying into geopolitical control zones.

For the most vulnerable communities, restoring environmental co-operation is the most promising solution to hedge against the effects of rising tensions or a rapid thaw. Their voices are calling on leaders in the North to rise to the growing challenges and break down the barriers in our shared cryosphere.