Back in the days when computers and space exploration were solely within the realms of science fiction, nobody could imagine having a chat with a machine, at least not outside the pages of a comic book. Not any more. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is real. It’s now relatively simple for tech-savvy people to create a conversation between characters who don’t exist or who died some time ago and even their closest relatives are unlikely to spot that it’s what’s called a “deepfake”. How can anyone know if they’re talking to a real person or not? Giacomo Miceli is an Italian-American computer scientist who created a totally false conversation between the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek and the German film maker Werner Herzog that sounded so much like them that even their close friends and relatives would probably have been convinced. The computer imitates accents, speech mannerisms and even occasional mispronunciations with stunning accuracy, enabling the programmer to make the subjects say whatever he or she may choose, and say it convincingly. Miceli initiated what he calls the “Infinite Conversation”, using cloned images and cloned voices. “We’re about to face a crisis of trust,” Miceli warned in the science magazine Scientific American, “and we’re utterly unprepared for it.”

Just take a look at ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence chatbot developed by OpenAI and released in November 2022, which put such accurate fakery within the grasp of anyone who wants to create conversations that never really happened. Assuming they possess the necessary skills, of course. Whatever we may think, the companies and people involved in technology development see it as very much the future. Whatever Miceli may think about it, it’s the next big thing, and getting bigger all the time. Quite apart from OpenAI, lots of tech companies are either striving to catch up or to get into the lead. OpenAI now has the backing of the giant Microsoft, while Google has published a paper about how a similar programme can create music. It goes without saying, of course, that China is trying to get in on the act, too, through its tech developer and search engine researcher, Baidu. It’s the field that seems to be attracting technology’s brightest and best, because of its obvious interest. Using ChatGPT, somebody could create a convincing but totally fake chat between, say, someone’s political rivals, making them say dreadful things that could be illegal and certainly misleading.

This presents a problem for the European Union, which wants to be at the forefront with AI and chatbots but also realises that it will have to introduce regulations of some sort. On the other hand, it doesn’t want to frighten developers away. Europe has already seen a temporary ban on ChatGPT imposed by the Italian data protection authority, Garante, which was growing concerned about potential breaches of its data protection legislation.

That seemed to be more of a concern than that a real person – perhaps a senior figure in politics – could be made to commit libel or some other speech crime without the supposed speaker even being aware of it. Garante told OpenAI that it must be more transparent about how the information of the programme’s users is processed. Concerns have also been raised in France and Spain, but as of yet, the EU has no regulation on the uses to which AI can be put, although it’s been under discussion for more than two years. It’s not expected to be ready to go onto the statute books until at least 2025. That may not be soon enough, according to German MEP Axel Voss, who is one of the main drafters of the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act. He has pointed out that AI itself was nothing like as advanced two years ago as it has become since and in two more years it will have advanced further still.. It could mean that whatever legislation is agreed will be out of date and relatively useless before it can even be fully enacted.

AI has to learn its trade, too. It takes developers a long time to teach it the skills it needs, even though, as Miceli told Scientific American, machine learning is an AI technique using vast quantities of data to ‘train’ an algorithm so that it can perform the task it’s required to do. He also said that he’d built his endless conversation as a warning, because it’s getting easier and easier to create realistic but fake images, videos or speech, and they could swamp us with even more fake information than most politicians can manage. He also warned that language-generating AI “can quickly and inexpensively generate and churn out reams of text”. It may not always generate an opinion that the fake speaker would endorse in real life. The real Herzog, for instance, dislikes chickens in the real world but in the fake computer-generated conversation, he seems to express compassion for them. That’s quite alright by me: I like chickens, too. Indeed, according to the fascinating book “The Secret Life of Cows” by Rosamund Young (read it and you’ll never see farm animals in the same light again) hens like playing most of all. “In fact, that is all they ever do,” Young writes, “apart from eating, which they also seem to do non-stop. They enjoy everything, sing happy little songs and just have fun.” How could anyone dislike an animal that plays all the time and has fun? That would be the sort of idyllic existence many of us crave. However, to get back to AI, there are still problems, with a risk that Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, may take his company out of the EU’s jurisdiction if the new (as yet undecided) laws are seen as too restrictive. He has since downplayed the risk of leaving Europe, however, during a worldwide promotional tour. But most Europeans would probably agree that such potentially dangerous capabilities need to be governed by some kinds of regulation if they’re to be allowed to operate at all. A free-for-all wouldn’t help anyone.

| TODAY: POLITICS; TOMORROW: THE WORLD (AND BEYOND)

It’s clear that AI is the future and nobody wants to stand in its way. Countries that fail to embrace this exciting new technology will get left behind in the great march of progress. World leaders are seeking (and holding) meetings with senior figures in programme development, such as Google’s Chief Executive, Sundar Pichair, who is also Chief Executive Officer of Google’s parent company, Alphabet Inc. UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, for instance, met with him to discuss the need for “safe and responsible” AI amidst concerns that the technology could prove to present “an existential threat”. It’s already agreed that the development of AI that out-performs human intelligence is “inevitable”. AI will be essential for decision-making on the planned missions to visit Jupiter’s various moons. It is such a long way that it will take the six-ton JUICE spacecraft (the name stands for Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) eight years to arrive and, once there, it will have to make its own decisions as it seeks ways to examine more closely the plumes of water seen escaping from Europa or taking a dip in the sub-surface oceans suspected of existing on, say, Ganymede or Callisto, or even further afield among the many moons of Saturn, such as Titan and Enceladus. Saturn is the clear leader in the “moons” race, with 146 of them now having been identified at the time of writing, although only 82 of them have been given names so far. There could be many more.

Meanwhile, back down on Earth, AI promises faster, cheaper and much more accurate weather forecasting. It could prevent a repetition of a notorious example of inaccurate forecasting in the UK, where in 1987 a well-known television weather forecaster assured viewers that rumours of an impending hurricane were false. In fact, they were all too real and he was never allowed to forget the incident. AI may be able to prevent such incidents, but it can, in the wrong hands, be used for all sorts of other purposes. TikTok, for example, is accused of having been designed to secretly siphon off vast amounts of information from users that have nothing to do with the app’s prime purpose. You may wonder why, and you would not be alone in that. Information is always useful, but if you think about the messages you have sent or received from friends and family, it’s hard to see any monetary value, isn’t it? But it’s the permanency of the app’s working, not unlike the clock in the song, that sits at the heart of the piece (written, incidentally, in around 1876 by Henry Clay Work): “Ninety years without slumbering, Tick, tock, Tick tock”. An “Infinite Conversation” indeed, or almost.

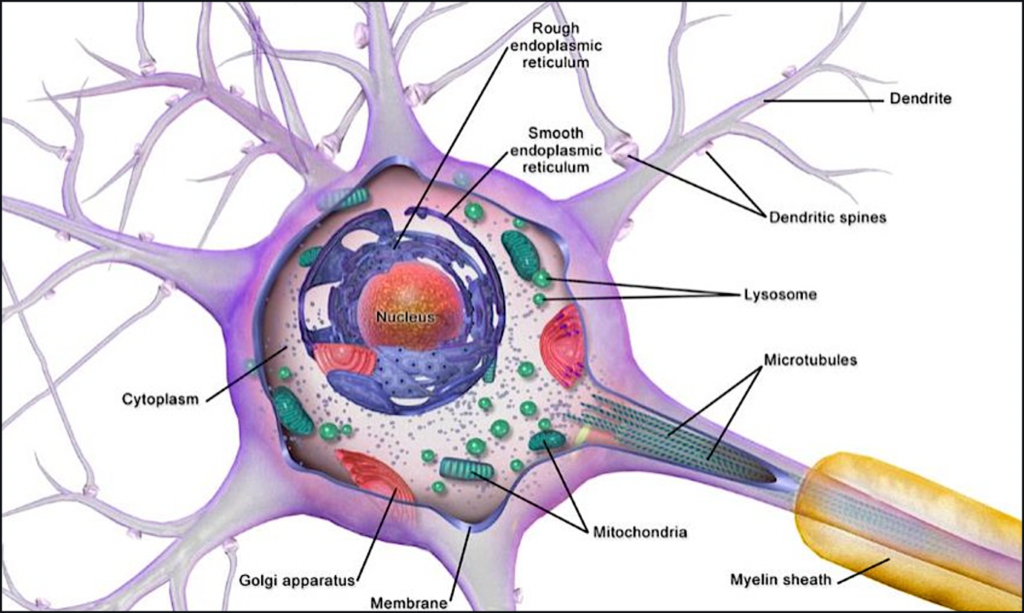

In fact, despite a massive amount of research down the years, the human brain is still in some ways a thing of great mystery. The striking advances in artificial intelligence are largely down to computers’ ability to engage in “machine learning”, in which they effectively teach themselves complicated and difficult tasks by running through all the available data over and over again. Computers, unlike their users, don’t get bored (at least, not as far as we can tell). The process involves what are called “artificial neural networks”, based theoretically on the networks of neurons in a human brain. Experts, both in electronic brains and human brains will tell you very firmly that it’s only a very loose comparison. The result is something called “artificial neural networks”, or ANNs. The real ones between our ears are much, much more complicated, of course, but they are already proving useful as analogues for the real thing. The very best ANNs appear to work very much like their biological counterparts. And they can be taught skills. The Economist reports on a study conducted at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2014 by neuroscientist Daniel Yamins for a study published in 2014 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in which an ANN was taught to pick out individual objects from a crowded photograph, such as an individual cat. The researchers, says The Economist, compared what had been happening inside the ANN with what had been going on inside the brains of macaque monkeys performing (or attempting to perform) the same tasks. They matched surprisingly closely, with the layers of artificial neurons working in exactly the same way as their biological counterparts.

| YES, BUT CAN IT JUMP THROUGH HOOPS?

Doctor Yamins’ report was later described as a “gamechanger”, and scientists have since said that OpenAI’s GPT-2 came closest to matching human brain activity. Research conducted at Columbia University at MIT in 2022 found that an ANN trained on image-recognition tasks produced a group of artificial neurons that could identify various foodstuffs. No-one at the time was aware of any part of the human visual system that could be said to be analogous to this food recognition system, but the following year one was found that fired off neurons more often when pictures of food were being shown. And there’s more. Researchers at the University of Texas in Austin set up a neural network to follow brain signals from people in an MRI scanner. Using nothing more than the MRI scan data, the ANN was able to produce a rough summary of a story that the test subject was listening to, and also a description of a film the subject was watching and even the “the gist of a sentence they were imagining”. That sort of thing has been the dream of researchers for decades, albeit more of a nightmare for some. What’s more, it’s something that somewhat unexpectedly provides a useful analogue for further research. Mind reading? Whatever next?!

Something known as Machine Learning (ML), apparently. The use of ML in conjunction with AI is becoming increasingly common, it seems. And it’s best done up close, not by relying on data in the cloud. Up close and personal is more effective and likely to be less expensive, too. There are several companies that specialize in facilitating such data transfers. As The Economist points out, ANNs make mistakes that no human would do but it’s easier (and rather more ethical) to poke and prod an ANN than a real human brain. It provides what The Economist calls “a useful alternative”. And let’s be honest: most of us would rather have a scientist poking around in an artificial neural network than using a scalpel on that mysterious material between your ears.

You may not be surprised to discover that AI is being used in the movie industry, and no longer as a persuasive motif for the storyline. In fact, some are describing it as “a gamechanger” in many areas, transforming the way movies are written and made, not just through clever special effects. Movie makers can save time and money by using machine learning algorithms to go through pre-existing scripts, harvesting data that can then generate new stories. It can even help with casting decisions, using its ability to process huge volumes of data to analyse previous performances and public reactions to them, including mentions on social media. AI could also help to speed up the film-making process by, for instance, finding objects needed for a particular scene by examining and analysing previous scenes from previous movies. It sounds as if it’s all positive, but there have been fears expressed that as AI gets ever-more sophisticated it could displace humans from the process altogether, with AI ultimately replacing human screenwriters, as well as creating ever-more impressive sci-fi movies through stunning special effects. As in other fields of endeavour, AI could lead to job losses, even if that material generated by AI lacks the emotional depth and human perspective that only real people can provide.

Let’s take a look at just a few of the implications. Well, for a start it means you can cast in a prominent rôle an actor or actress who is no longer alive. AI can copy that person’s looks and voice so perfectly that people are unlikely to realise they’re looking at and listening to a fake. It could lead to job losses in the industry, as AI has already done in such areas as design and manufacturing, for instance. What if your proposed movie requires music to match the on-screen mood?

AI can do that, too. One movie insider pointed out that AI can change everything by its ability to create something that doesn’t exist. Yes, it arouses deeply divided view about the underlying ethics of it all, but that is unlikely to produce a permanent barrier, and companies specialising in AI products and services for the movie industry are already rubbing their hands with glee in anticipation of the money to be made from what is already being promoted as a way to save money in carrying out the task.

AI can already be used to help plan filming schedules, in identifying suitable shooting locations, or even in analysing real world data against the requirements of the script, as well as helping editors to find particular scenes or camera angles. I’ve worked with a lot of cameramen and not all of them have that natural gift, although some undoubtedly do. AI’s main advantage, it would seem, is in saving time, whilst also ensuring smooth transitions and effective use of people and equipment in the operation. AI can automatically perform colour matching and put in place masks where required, even changing the facial expressions of the actors on screen. AI can also help to restore old film by taking out or covering up scratches, dirt, warping and flicker from old film stock. From an actor’s point of view AI can perform another task they may be pleased about by making them appear younger and by restoring their youthful vigour. If only that was possible in real life the entire world would be beating a path to the developers’ door. It’s called “de-aging” and I wish it worked in the real world! Sadly, it doesn’t.

| IN TUNE? WHO CAN TELL?

As for the musical score, AI can help there, too, composing original works that match the cuts, breaks, romance and excitement-generation of the images. After all, you don’t want romantic music to be playing as the background to a murder.

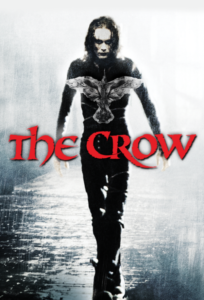

It wouldn’t work. It’s rare, of course, to come across a movie made entirely through the use of AI or by employing ANNs, although one computer artist has won the Cannes Short Film Festival Jury Award for his text-to-video production, “The Crow”. Other people have also used AI to produce video, and it’s a skill that looks set to expand more in future. We’re not quite there yet, however. Those involved in the process know that we’re not quite ready to drop human beings from the equation. AI can undoubtedly speed up the process, and that will almost certainly improve the profit margin. Film-making, though, is still an expensive activity and likely to remain that way, however much AI can save time and resources. AI can improve the accuracy and efficiency of casting decisions and there are fears that AI could displace human participants such as screen writers, casting directors and others involved at the coal face of making movies. Some who are deeply involved have also expressed the fear that AI will almost certainly lack the human touch that comes from personal experience. AI, after all, is not strictly human, however clever the app developers have been in trying to make their creation reflect the real world. Some jobs would simply be impossible – or certainly extremely difficult – for an AI to perform convincingly. Such tasks could include displaying human empathy, social skills or even human dexterity. It’s too early to write off the enormous contribution that living, breathing human beings can bring to the world of making movies.

According to The Hollywood Reporter magazine, AI is now involved at every conceivable level of the movie industry, and the Writers Guild is pushing for protection from its invidious invasion of creative space. Even more threatening than chat bots and AI-generated videos, the paper reveals, the worst things of all are the black box algorithms that decide what is popular. “In Hollywood,” the paper reveals, “producers are rewarded with lucrative film deals for developing projects that feed the black box AI at studios and streaming platforms, which keep valuable viewership data insights to themselves.”

The article continues: “That viewership data is built via feedback loops created by recommendation engines reinforced by the very viewer behaviours they shape in the first place.” The article claims that while the Writers Guild is right to push for protections against AI, “nowhere are these protections more urgent than in the documentary and non-fiction space,” which is where the writer of the article works. Amit Dey, Executive Vice President for non-fiction at MRC, said: “It’s one thing if human-made films are competing in the market against robot-made films. It’s another thing entirely when data in the form of artificial intelligence, or proprietary algorithms, shape the decisions around what human audiences are exposed to.” His point, of course, is that it cannot be right to have the decisions about what we get to see made by robots somewhere. But that is what’s happening right now. And it shouldn’t be, in the view of The Hollywood Reporter. “Without smart (human) executive intervention,” it warns, “challenging our basic instincts as viewers to tap relentlessly on puppy videos, is viewership engagement on the majority of these platforms even that great? For TikTok, maybe. From a more sophisticated aesthetics standpoint, the unchecked race to maximise viewer engagement is a race to the bottom.” It’s hard to argue convincingly on that point.