Rendering of China’s Chang’e 5 lander after touching down on the moon © CCTV

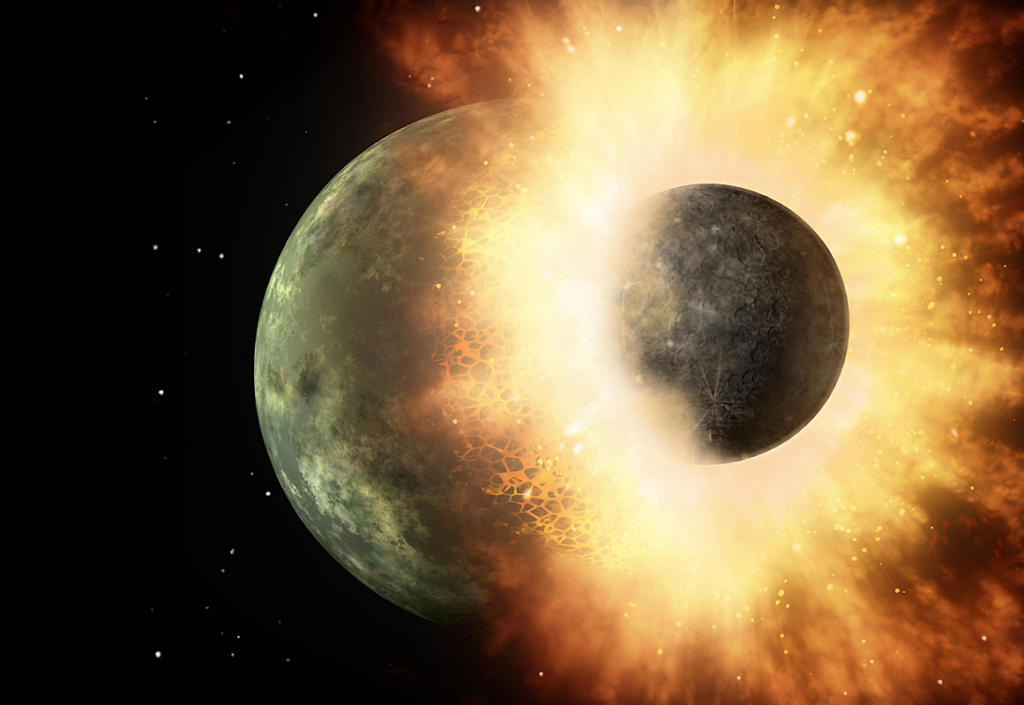

Earth’s Moon is rather unusual. It’s too big, for one thing. Its diameter is almost 28% that of the Earth, making it proportionately the largest satellite our solar system can boast. The next biggest, in proportion to its host planet, is Neptune’s largest moon, Triton, which comes in at just 5% of the diameter of the planet it orbits. So here we are, only the 5th largest planet of our solar system, encircled by what is, coincidentally, the system’s 5th largest moon, proportionately. This has led to a lot of speculation about its origins. Charles Darwin’s son, George, believed it had been spun off the Earth, leaving a big hole that we know as the Pacific Ocean. A more popular belief today is that it was caught unawares (as if a planet could ever be aware of anything anyway) by a slightly smaller, perhaps more Mars-sized planet which astronomers refer to as Theia. In that version, known as the “Giant Impact Hypothesis” (GIH) the two bodies collided and sent up a huge mass of debris which coalesced into our Moon. That, they argue, is why it is less dense than Earth and has an oddly undersized core. Its surface is covered with geological features that Earth-based scientists have given very poetic, even atmospheric-sounding names. That’s odd, because, of course, the Moon has no atmosphere at all. It would not be a good place for a romantic tryst with your loved one. Earth, however, is denser than our neighbouring planets, which has led to suggestions that the heaviest parts of Theia stayed close to Earth, eventually merging into it. The lighter parts were thrown further out and formed – eventually – into the Moon, which, as a consequence is much less dense than Earth, and, as samples brought back from the Apollo missions showed, have a slightly different mix of oxygen types. Computer simulations suggest that the Moon is mainly made up of material from Theia, if it existed.

This would suggest that the Moon, containing so much of Theia, should be made of the same material almost exclusively, but China’s space researchers would beg to differ. They have now discovered a new lunar material – the sixth so far. And there could well be more. In a joint statement, the China National Space Administration and the China Atomic Energy Authority have announced the discovery of what they call Changesite – (Y), which was found amongst samples that were brought back to Earth by the Chang’e 5 robotic mission.

It was named after careful examination at the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology and it was subsequently certified by the International Mineralogical Association and its Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification. Changesite – (Y), which comes under the heading of ‘lunar merrillite’, comes in the form of a single-crystalline particle with a diameter of 10 microns, and it was separated out from other material that was formed of some 140,000 tiny particles before being analysed through a series of very advanced mineralogical means, according to the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology, which is one of the most important institutes to come under the China National Nuclear Corporation. The chief scientist for lunar sample research at the Institute, Li Ziying, has said it will help researchers trying to learn more about the history and true geological nature of the Moon. It’s been there all this time, seeming to smile down on us humans, yet we know relatively little about it.

Li told the media that the location upon which the Chang’E – 5 probe landed and from which it gathered its samples is younger that the landing sites of earlier US and Russian missions, which could mean new characteristics not seen on earlier visits. Furthermore, scientists at the Institute have also measured the contents and characteristics of soil samples brought back on earlier US and Soviet missions. They have measured the helium-3 that the probe found which could provide the perfect fuel for future nuclear fusion power plants. “The results will facilitate the prospecting and assessment of the resource on the Moon,” Li said. Using the Moon’s vast supplies of helium-3 as a potential power source is not a new idea but it has never seemed like quite such a realistic prospect before. According to one estimate, more than a million tons of helium-3 (3He) has been deposited on the surface of the Moon which has left the concentration level at between 1.4 and 15 parts per billion (ppb) and may even contain concentrations as high as 50 ppb in areas that remain permanently in shadow. Obtaining the required 3He would not be easy. According to Wikipedia, the comparative concentration on Earth is closer to 7.2 parts per trillion (ppt), which is one reason, perhaps, why nobody has yet come up with a functioning small fusion plant. The very low concentrations mean that – according to one estimate – obtaining 1 gram of helium-3 would require the careful processing of 150 tons of regolith. Regolith is, of course, the weathered debris of soil and sediment that has been mixed together and is normally found above bedrock. Processing the volume required would offer a very small return for a lot of effort. Furthermore, by no means all scientists think the idea is even feasible. Even if it proved possible to extract 3He on the Moon, no fusion reactor yet designed would appear to produce more power than the amount required to make the extraction process work, which would appear to render the exercise somewhat pointless.

Chinese scientists from multiple research institutes and universities have created the high resolution topographic map based on data from China’s lunar exploration Chang’e project and other data and research findings from international organizations .The map includes 12,341 impact craters, 81 impact basins, 17 rock types and 14 types of structures, providing abundant information about geology of the moon and its evolution © Institute of Geochemistry of Chinese Academy of Sciences

| THE ENERGY OF HOPE

One optimistic note is the sheer volume of 3He to be found on the Moon. Experts have estimated that only some 15 to 20 metric tons of Helium-3 are to be found on Earth in total. This paucity of supply would appear to hamper its usefulness as a fuel, but experts have suggested that there could be a million tons or more on the Moon. It would appear, perhaps, that Theia got the lion’s share of the stuff when it separated from Earth (assuming it existed at all). The Chinese spacecraft that made this historic discovery was launched from Wenchang Space Launch centre in South China’s Hainan province on 24 November 2020, landing just seven days later. On its return to Earth on 17 December, it brought back 1,731 grams of rock and soil, a remarkable achievement and the first load of Moon rocks to be brought to Earth for roughly 44 years. Once back here, according to the China National Space Administration, the samples, weighing a total of around 17.5 grams, were divided up into 21 separate lots which were later (quite a lot later) shared out among thirteen separate domestic research organisations working on 31 different scientific projects.

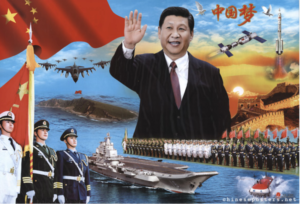

So, everybody happy and excited? Perhaps they should be, but if two wolves come across a single deer carcass out in the wilderness, it’s not in their nature to share. The US has been issuing warnings that China wants to “claim” parts of the Moon for itself. “It is true that we better watch out that they don’t get a place on the Moon under the guise of scientific research,” warned NASA administrator Bill Nelson, adding: “And it is not beyond the realm of possibility that they say, ‘Keep out, we’re here, this is our territory.” Nelson went on to warn that he believes Beijing’s interest in space would in some way be to claim ownership over the Moon and stop other countries from exploring it or conducting missions where its space stations are located. He was effectively reiterating the concerns already expressed by International Space Station (ISS) commander Terry Virts, who has also issued warnings about what he called Beijing’s “potential mischief” in trying to make the Moon a part of China. I’ll start worrying when a first bar opens there offering crispy seaweed or chicken chop suey opens in Copernicus Crater or the Sea of Tranquility. Not a lot of passing trade, I would imagine, but if one did open for business, I’d lay odds it would be American-owned.

Still, if you can use those supposedly cheap-fuelled nuclear fusion heaters to cook the stuff, I don’t rule anything out. I love Chinese food (despite being a vegetarian) but the Moon is a very long way to go for a snack. Still, America seems worried: in a detailed 196-page report, the US Department of Defense (DoD) underlined China’s persistent attempts to step up its space programme with the aim of landing a spacecraft bearing China’s flag on some new site on the Moon where neither human nor robot has ever ventured before. Virts had already told the newspaper Bild that by 2035 China will complete the construction of a Moon station and will also launch several space flights to, as he alleged, “hijack the Moon”. Do we shout out “bring it back!” now or later? China has already managed to get seeds to sprout on the Moon, which is more than any other country has done so far, and China is running second only to the US in the space race. It is a source of considerable national pride there, a part of what Chairman Xi Jinping has called “China’s Dream” (could it also be Washington’s nightmare?) and part of his plan to build a powerful and prosperous China. Perhaps someone should ask the Uighur people what they think about that.

Back in 2019, China became the first country to land a space craft on the far side of the Moon. It was the Chang’e 4 lander, bearing the Yutu 2 rover that touched down in the Von Kármán crater. It also set a longevity record with both lander and rover active for more than one thousand Earth days while the rover explored almost 840 metres on the far side, incidentally capturing some stunning photographs and also overtaking the record set by the Soviet Union’s Lunokhod 1 rover of 321 days of work on the lunar surface.

America’s assertion that China has territorial ambitions on the Moon have been dismissed by the Chinese government as “a lie”. In a statement, China said: “Some US officials have spoken irresponsibly to misrepresent the normal and legitimate space endeavours of China. China always advocates the peaceful use of outer space, opposes the weaponization (of space) and arms race in outer space, and works actively toward building a community with a shared future for mankind in the space domain.” Wonderful sentiments, if true.

| COME QUICKLY. BRING A BUCKET

We’ve talked quite a lot about helium-3 without mentioning the new mineral that Chinese scientists have found, changesite-(Y). For a start, it contains helium-3, which makes it interesting straight away. Helium-3, by the way, is a heavier isotope of helium, while changesite-(Y) takes its name from Chang’e, China’s mythological moon goddess, who also gave her name to China’s first lunar rover designed to collect samples from the moon’s surface, a job it fulfilled admirably. In appearance, changesite-(Y) forms a transparent and colourless column, a mere 10 microns in radius, which is less than one tenth of the diameter of a human hair. It could provide a very rich source of nuclear fusion energy, so there may prove to be quite a heavy demand for the stuff, if anyone can find a way to harvest it in sufficient quantities. The changesite-(Y) that has been returned to Earth was found near Mons Rümker, a volcanic formation on the Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms), a primarily basalt area. As Wikipedia explains, basalt is a fine-grained igneous rock formed in the rapid cooling of a form of lava rich in magnesium and iron, close to the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90% of all the volcanic rock on Earth is basalt. The region from which the changesite-(Y) was recovered was formed during lunar volcanic eruptions billions of years ago, which means that the samples came from deep inside the Moon a very, very long time ago when there were still active volcanoes on the Moon. For those with a chemical inclination, the formula is (Ca8Y)□Fe2+(PO4)7. Changesite-(Y) is a Merrillite mineral, which means it’s made of calcium phosphate and has the chemical formula Ca9NaMg(PO4)7. It is also rich in sodium.

As for those volcanoes on the Moon, they are currently regarded as “dead”, having burned out and inevitably cooled down. Many scientists would like to take a closer look at the Moon’s mineral riches, since knowing more about how that cooling down took place should give us a glimpse of what lies in store for the planet Earth at some distant future point. Politicians involved with the space research of the United States are rather more concerned about political outcomes. After all, back in 2009, Zhang Kejian, the head of China National Space Administration (CNSA) and Dmitry Rogozin, General Manager of Russia’s space research body, Roscosmos, signed a Memorandum of Understanding for the construction of what was intended to become the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) on the Moon. The facility was intended to be capable of long-term operation either on the surface of the Moon or on-board a spacecraft in orbit around it. This fits into the prediction by Terry Virts that China would complete the construction of its own “Moon station” by 2035. That’s why China planted and grew plants from potato seeds, rapeseed and rare types of cotton seed, all sprouted on the Moon. I wonder who waters them? They must have needed a watering can with a very long spout. The West must stop drawing the wrong conclusions, says Beijing and “amend the negative comments”, and it should also “make the due contribution of the US to maintaining continued peace and security in outer space.” Let’s face it: a real war being fought among the planets (we can forget the stars in this context) would be very unlike the spaceship-to-spaceship battles of the kids’ comics of our youth. Poor old Dan Dare wouldn’t get a look-in.

| HOME SWEET HOME

It would be worthwhile to look at our home planet and its immediate neighbourhood. Our particular planetary system is in an outer spiral arm of the Milky Way galaxy, comprising the Sun and the various lumps of rock bound to it by gravity: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, along with a clutch of dwarf planets of which the most famous is Pluto, whose diameter of 2,368 kilometres means it’s smaller than our Moon, at 3,476.

It’s a strange place, the solar system. In addition to those dwarf planets, we have the Kuiper Belt, a disc of matter going around the Sun and stretching from the orbit of Neptune at 30 astronomical units to some 50 astronomical units. An astronomical unit is roughly the distance between Earth and the Sun: around 150-million kilometres (or 8.3 light-minutes if you prefer). Beyond the Kuiper Belt – quite a long way beyond – we have the Oort Cloud, thought to be the most distant part of the solar system with even its nearest elements many times further out from the Sun than the outermost parts of the Kuiper Belt. It is thought to comprise billions – or perhaps ever trillions – of icy pieces of space rock ranging in size from pebbles to rocks the size of large mountains. In fact, the Oort Cloud is believed to form a massive thick-walled shell around the rest of the solar system. There may be more, extending out even further from the Sun towards its nearest solar neighbour within our home galaxy.

Now, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has photographed countless thousands of other galaxies, stretching away not only in space but in time. It has delighted and surprised the scientists involved in its deployment with photographs of galaxies so far away from us that they must date from a time when our universe was young. Positioned around 1.5-million kilometres away from where it could suffer interference from Earth, it has been looking into galaxies so distant that they must have begun to form just a few hundreds of millions of years after the so-called “Big Bang” that set the whole thing in motion. In astronomical terms, that’s hardly any time at all. We can now look back at the origins of our place among the stars and, indeed, at those earliest of stars themselves.

The December 2022 edition of Scientific American shows images taken by the JWST of, for instance, the Carina Nebula, where many hundreds of hitherto invisible new-born stars are beginning to twinkle some 7,600 light-years from Earth. Whatever Beijing, Washington or Moscow may say, no-one will ever be able to claim them, although Washington can certainly be able to claim that it got the first photographs. The images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, launched into low Earth orbit in 1990, and now by the JWST, launched on a European Space Agency Ariane 5 rocket on Christmas Day 2021 (The Ariane 5 was chosen as the launch vehicle because of its reliability) have allowed us to peer through billions of kilometres of space dust into what is, as far as we’re concerned, the dawn of time. In terms of the numbers of galaxies revealed and the clarity of their reproduction, the pictures from the JWST surpassed all expectations. It makes a trip to the Moon seem almost trivial by comparison, although of course it certainly isn’t.

| FAR AWAY AND EVEN FURTHER

It has to be hoped that the JWST doesn’t need any repair or servicing. The Hubble has an altitude of just 600 kilometres, which is reachable. The JWST, on the other hand, is at the Sun-Earth Lagrange point at an altitude of 1.5-million kilometres, and there are currently no plans to design or construct a space vehicle that could give engineers access. Incidentally, Lagrange Points, named in honour of the Italian-French mathematician Josephy-Louis Lagrange, are positions in space where two large masses exert matching gravitational pull, so that a space vehicle can remain in position without using fuel to stay where they need to be. In this case, the gravitational attraction comes from the Sun and the Earth.

Getting the photographs is no easy matter, however rewarding. For instance, the galaxies known as Stephan’s Quintet, some 290-million light-years from Earth, occupy an area of space equivalent to around 20% of our Moon’s diameter, so the photograph (also reproduced in Scientific American) is made up of almost a thousand separate images, but together they reveal details of the galaxy group that have never been seen before. When we consider the vast distances involved, and the eons of time, the influence of one Earthly country over the planet’s Moon would seem to be a trivial matter, of relatively little importance. Our Moon may be bigger than it should be in relative terms but it doesn’t come near to the size of just one of the many galaxies now being revealed by the JWST. Squabbling over who it belongs to begins to look rather silly, but that’s politics for you.

All the same, it would be wrong to downplay China’s great achievement in getting its rover onto the Moon and bringing back rock samples that include a totally new mineral. Finding changesite – (Y) and successfully identifying it by giving it a name is an amazing thing to have done. Of course, there is much more still to do and it would be better for all of us if the various space-venturing nations worked together instead of competing – China, the United States and even (if it stops its pointless but bloody war in Ukraine) – Russia. Imagine what they could achieve through cooperation. That, however, may be a goal that’s more difficult to reach than a distant part of the Oort cloud, or even those distant galaxies discovered so magnificently by the JWST. Trying to out-do each other in the space race – as in other endeavours involving national pride – is a fairly pointless endeavour. I think Mahatma Gandhi had a valid point when he said: “An eye for an eye will only make the whole world blind.” With so much that’s new to look at and so much more yet to see, that would be a terrible waste.

Jim.Gibbons@europe-diplomatic.eu