A fully assembled model of the Ariane 6 © ESA/Manuel Pedoussaut

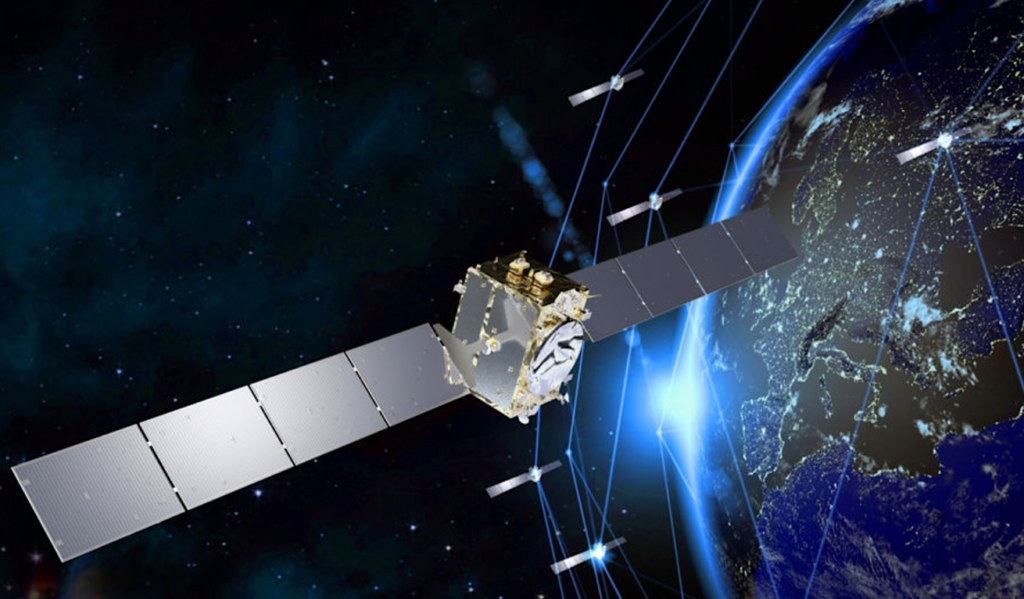

“Time and space are not conditions of existence, time and space is a model for thinking.” That’s what Albert Einstein said and, let’s face it, he should have known if anyone ever did. However, Europe has, it would appear, been slow to think much about space. At last, that is changing, with the IRIS2 project. IRIS2 is set to be a constellation of satellites designed to enhance communication possibilities, especially for governments and business users, as well as making sure of high-speed Internet broadband, hopefully eradicating dead zones where connections are difficult. In our modern world it’s vital that communications are fast and reliable, and as anyone who has tried to get in touch with someone over the Internet will know only too well, that’s not always easy, or even possible. The hope is that with IRIS2 in place such difficulties will be consigned to the past. Like everyone else, the EU has an increasing need for a secure and reliable communications infrastructure. The European Parliament has approved a budget of €2.4-billion, with the money coming from member states via the European Space Agency (ESA), as well as from industry, but the European Commission reckons the total cost will come to around €6-billion, with the public sector contribution from 2023 until 2027 of around €2-billion at current prices. The Commission says that when it comes to the provision of commercial services, the private sector is poised to invest in order to develop and deploy related infrastructure. If it all comes together and works as it’s supposed to, we all stand to benefit. Probably.

The requirement for such a system was highlighted by Ukraine’s need for satellite telecommunications because of its unwanted war with Russia and Europe’s inability to supply such facilities. Regarding that unprovoked conflict reminds me of another quotation from Einstein: “Only two things are infinite, the universe and human stupidity, and I’m not sure about the former.” Setting that aside, we cannot forget the vast satellite constellation created by the American billionaire Elon Musk.

Musk’s SpaceX company has put around a thousand satellites into orbit some 550 kilometres above the Earth, which is only around half the altitude of most artificial satellites. The plan is known as “Starlink”, and it comprises so many satellites, in fact, that some people have expressed fears over the risk of possible collisions. Musk has said all along that his aim is to provide communication possibilities with the most remote parts of the planet (want to make a phone call home from Antartica?). Nobody need ever fear that they’re not being served or that they cannot contact others ever again! According to the website “Space.com”: “A Starlink satellite has a lifespan of approximately five years and SpaceX eventually hopes to have as many as 42,000 satellites in this so-called ‘megaconstellation’.” One single SpaceX Falcon rocket managed to launch 143 satellites on board a single vehicle recently and it’s been estimated that Earth could soon have a million satellites whizzing around up there. But with such relatively short life spans, they will need frequent replacements. Even so, Europe clearly has a lot of catching up to do. Meanwhile, Musk’s SpaceX team is planning 144 launches in 2024 alone, which means twelve each month, or one every two and a half days. The company plans simultaneously to increase its launch rate, driven by the desire to have satellites that can connect directly with mobile phones: the “direct-to-cell facility”, as it’s been dubbed, working in conjunction with T-Mobile. SpaceX has also vastly improved its ability to track down and recover used launch vehicles, too, so that they can be refurbished and reused, representing an enormous saving financially.

| TAKING UP MORE SPACE

Thales Alenia Space is one of the enterprises that will lead the European consortium in the Iris2 satellite constellation programme © Thales Alenia Space

So, will there be room up there for another competitor in the satellite communications business? As it is, Amazon has also entered the fray, with its Project Kuiper plan to launch yet another constellation of satellites. From the EU’s perspective, IRIS2 means a more general, non-affiliated provider than the Musk operation or Project Kuiper could be, both being rooted in big business. IRIS2 is also supposedly non-political, enjoying (if that’s the right expression), the support of the Renew Europe political grouping, which describes itself as a Liberal pro-European political group, with membership widely spread among the member states. The group hopes that by providing new services in the space sector it will help to foster “a completely new ecosystem of start-ups and SMEs as well as the emergence of innovations and new services in the European space sector”, and additionally helping innovations and new services in the sector. MEP Christophe Grudler of France’s Mouvement Démocrate, who is also the Rapporteur on the EU secure connectivity programme pointed out how Russia’s unprovoked aggression against Ukraine had given the whole plan impetus. “With the war, Ukraine needed satellite telecommunications, but the EU didn’t have something to offer,” he said. “Ukraine should not have to rely on the whims of Elon Musk to defend their people.” We must ask ourselves if this new plan will change things; he thinks it will: “With, IRIS2, the EU will have its own telecommunications constellation, able to offer secure communications to European governments and allies.” But, as I said earlier, the EU will have some serious catching up to do, if it’s to play with the big boys, however confident Christophe Grudler may sound. He told journalists: “I’m proud that this constellation will also set a worldwide example in terms of sustainability, as we requested.” It all sounds very promising, with him adding: “Now is the time to build these new European satellites and prepare them for launch.”

We should not forget, of course, that this isn’t the EU’s first venture into space. Europe’s very own GPS system, employing its Galileo satellites, is used by some two billion mobile devices around the world. The EU also has its Earth observation Copernicus satellites up there, not to mention the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, which is still discovering new facts about our galaxy and how it formed, so this new project will be far from the EU’s first venture in terms of space research. We’re all space people these days. The old competitive nature of it all seems to have back-pedalled slightly. I still remember the excitement in April 1961 when Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man ever to fly in space. It was just before my 13th birthday, and I was delighted. I was similarly thrilled when Alan Sheppard, an American Astronaut, followed him into space in May of that same year. He was followed, of course, by John Glenn, an American and the first man to orbit the Earth. There were many more, but nobody and nothing exceeded the excitement generated in 1969 with Neil Armstrong took his “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” by stepping onto the surface of the Moon. Nor will they, I think. It was just too important and thrilling.

Where next? Venus is a fiendishly hot and deadly place where humans cannot go, while Mars is just a bit too far away and would require the carrying of vast stocks of food and drinking water, there seeming to be none there that’s easily accessible. Whatever those strange people who claim to have seen UFOs (Unidentified Flying Objects) or say they’ve been visited by aliens may post on-line, any alien races there (there aren’t any really, I don’t think) may be unimpressed by our tentative steps into space exploration. After all, as astronaut Buzz Aldrin said, “There may be aliens in our Milky Way galaxy, and there are billions of other galaxies. The probability is almost certain that there is life somewhere in space.” It just hasn’t chosen to pop by for a cup of coffee and a quick ‘hello’, it seems.” I’ll keep the coffee machine handy in case they do, though. We should, perhaps, recall the words of the American astronaut, Scott Carpenter, who wrote that: “At no time when the astronauts were in space were they alone, there was constant surveillance by UFOs”. Nobody bothered to wave at them, it seems, nor to film them, which is odd. So next time we go out for a walk after dark, maybe we should look up at the sky, wave your hand and say: ‘Hi, guys’.” But bear in mind that if they’re out there, the aliens are unlikely to speak English (or Chinese, or Russian, Congolese, or Brazilian). Maybe that wave will be enough (unless in their sign language it means “please attack us viciously”). Only joking.

| THINGS CHANGE, EVENTUALLY

The plain fact is that space is simply huge. Earth’s sun and its local retinue of planets, moons, and other lumps of circling rock (which includes us, of course) travel around the centre of our galaxy at the impressive speed of 250 kilometres per second, but even so, it takes some 200-million years to complete one circuit of the Milky Way galaxy. Everything about space is bigger and takes far longer to reach, even for light waves, than mere humans can comfortably comprehend. You think you know the shape of the various constellations up there (such as the Plough, for instance, also known as “the Big Dipper”), but in a few years – say 100,000 years, for instance, which is nothing in galactic terms – it won’t look the same at all: its familiar seven stars will have moved off in different directions from each other and may not form any recognisable shape at all. It’s now known that our Milky Way has swallowed whole galaxies in the past (quite a long time ago, however; possibly as far back as some ten billion years) and will continue to do so in the future. A lot of smaller galaxies revolve around our galactic core and in the fullness of time (admittedly a very long time) they will merge with our galaxy and with our neighbour, the Andromeda galaxy, which is currently a round 2.5 million light years away from us, and new stars are forming in its dust clouds constantly, if somewhat unobtrusively. Exciting times lie ahead but it seems very unlikely that any of us alive today will live to see it. Even so, we do know a lot more than we did. For instance, NASA’s COBE mission has revealed that the many, many galaxies out there are not spaced evenly but in random-seeming clumps. I’m not sure how that helps us to make sense of the cosmos but knowing more is always better than knowing less.

The Commission points out, however, that no astronomy-related applications are foreseen within the IRIS2 programme, although the European Space Agency Gaia mission has discovered additional data on some 1.8-billion stars and also on globular clusters, which include some of the universe’s oldest and most interesting and even venerable objects. “In Omega Centauri, we discovered over half a million new stars Gaia hadn’t seen before – from just one cluster!” said lead author Katja Weingrill of the Leibniz-Institute for Astrophysics, Potsdam (AIP), Germany, who is a member of the Gaia collaboration.

Even so, with so many satellites already zipping around up there, you may wonder why we need more. The European Commission is very clear on that point: “The new Satellite Constellation named IRIS2, is the European Union’s answer to the pressing challenge of tomorrow, offering enhanced communication capacities to governmental users and businesses, while ensuring high-speed internet broadband to cope with connectivity dead zones.” There’s more to it than that, of course. The European Commission again: “The system will support a large variety of governmental applications, mainly in the domains of situational awareness (such as border surveillance), crisis management (which includes humanitarian aid, of course) and connection and protection of key infrastructures, such as secure communications for EU embassies.” The Commission seems to believe the network will pay for itself in the long run: “On the commercial side, it will allow mass-market applications, including mobile and fixed broadband satellite access, satellite trunking for B2B (Business-to-Business) services, satellite access for transportation, reinforced networks by satellite and satellite broadband and cloud-based services.” It would seem that the EU believes, if you’ll excuse the pun, the network will really take off, although it’s not planned to put it into service until 2027.

| TWINKLE, TWINKLE

According to a European Commission press release, we are now moving into what it calls “a new digital era”, which means that our economy and our security will depend increasingly on secure and resilient connectivity. By the way, the IRIS name is an acronym for “Infrastructure for Resilience, Interconnectivity and Security by Satellite” (hence the two “S”s). The Commission has pointed out that cyber and other hybrid threats to our security and success are multiplying, so the EU has come up with a plan to develop state-of-the-art new connectivity systems that can support a wide variety of government applications but also help with crisis management when emergencies occur without introducing any new restrictions or, indeed, dangers in terms of spying by hostile forces. In the Commission’s own words, through its use of new technology and the EU’s existing agencies, IRIS2 should support “the economic and societal growth of the EU while supporting social cohesion through the reduction of the digital divide”. It may also make your mobile phone and Internet connections more reliable, which can only be a good thing, I imagine. The Commission also says that “dedicated payloads on-board the envisaged system are expected to improve and expand the capabilities and services of other components of the Union Space Programme.”

The EU’s satellites certainly wouldn’t feel lonely up there, even if they were to be capable of such feelings. China, for instance, is developing a similar constellation of satellites, but the EU is understandably uneasy about handing such power (as well as access to communications) to a country whose intentions may be suspect. Another option is the UK’s “One Web” network, but apart from having left the EU (not its brightest decision in my personal view), it may not have the necessary capacity to run a reliable global service, or one that is sufficiently large to look after Europe alone. SpaceX launched its first two experimental satellites for its Starlink network in February 2018.

There’s a lot of competition to use the endless resources of space. Endless it may be, but even so low-Earth orbits will place some of the satellites close enough to each other for interference to occur. The UK’s communications regulator, Ofcom, has already highlighted the risk in a report. It seems that some of the existing licences already issued to SpaceX and OneWeb may have to be amended in order to require co-ordination of use. Otherwise there could be a risk of what are called “in-line events”, in which some satellites accidentally come into line with one another. The one nearer the receiver dish could – in theory – mask the one behind it and block its signal.

The Commission has stressed the growing importance of “secure and resilient global space connectivity”. To ensure this resilience, and to avoid creating new technological dependencies, the Commission has proposed a new programme on secure connectivity, especially to ensure what it calls the “security-and-safety-critical missions and operations managed by the EU and its member states, including their national security actors and EU institutions, bodies and agencies”. It should also help to reinforce the competitiveness of EU industries. “IRIS2 will entail the development of a multi-orbital constellation of satellites,” says the Commission, with notable enthusiasm, “Such a constellation would provide ubiquitous high-speed broadband in Europe and the rest of the world, and reliable, secure, and cost-effective connectivity to support governmental and commercial secure communications.”

With so many actors involved already in the provision of new satellite communications, do we need yet another, even one bearing the EU’s emblem? I asked the Commission if IRIS2 is really necessary or if it is simply to ensure that the EU remains firmly on the map where space is concerned?

In other words, is it a primarily practical or political undertaking? “IRIS2, the new infrastructure for Resilience, Interconnectivity and Security by Satellite,” came the reply, is a “flagship programme that pursues the objective to provide critical services to European public authorities and citizens, such as reliable, secure, and cost-effective connectivity for governmental and commercial communications, as well as ubiquitous high-speed broadband availability throughout Europe. This will allow Europeans to be and to remain connected.” Indeed, the entire project doesn’t seem to have a negative aspect, at least at first glance. However suspicious we may be of Elon Musk or the Chinese, here comes Europe with a safe and politically neutral alternative. “By promoting forward-looking opportunities,” the Commission spokesperson continued, “it will enhance Europe’s strategic autonomy and resilience by means of a new satellite infrastructure, technological leadership, and geopolitical influence, including in the Arctic and Africa.”

| IT IS NOT IN THE STARS TO HOLD OUR DESTINY (Shakespeare)

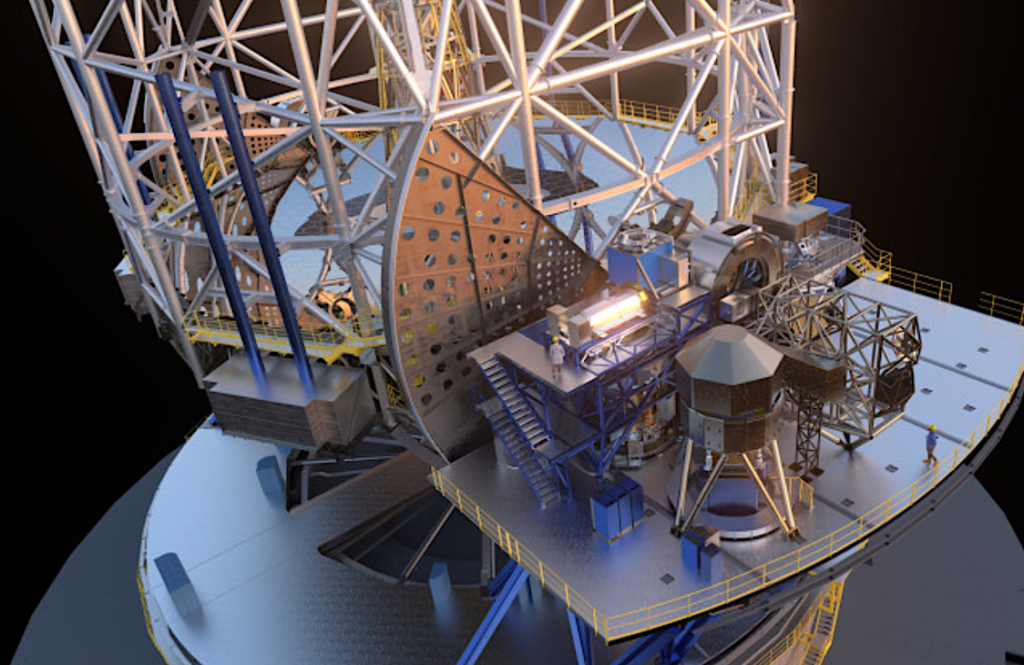

As I said, it all looks hugely positive with no downside at all. Well, there is a downside, if you’re an astronomer, according to Scientific American magazine . “Rachel Street felt frightened after a recent planning meeting for the Vera C. Rubin Observatory,” it reported. “The new telescope, under construction in Chile, will photograph the entire sky every three nights with enough observing power to see a golf ball at the distance of the moon. Its primary project, the Legacy Survey of Space and Time, will map the galaxy, inventory objects in the solar system, and explore mysterious flashes, bangs and blips throughout the universe.”

And all those satellites, put up there by Elon Musk, the Chinese, the EU and others could block some of the view and interfere with the observations, creating what the magazine calls “bogus stars”. Some serious astronomers are now talking about making their observations as early as possible, before the spread of artificial satellites clogs up the view. For Scientific American, this is a very serious issue that will have to be addressed, sooner rather later. “As low-Earth orbit fills with constellations of telecommunications satellites,” the magazine informs us, “astronomers are trying to figure out how to do their jobs when many cosmic objects will be all but obscured by the satellites’ glinting solar panels and radio bleeps.”

Since the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 back in October 1957, continuous launches, mainly into low-Earth orbit, have ensured that we are now constantly surrounded by more than 5,400 artificial bodies encircling the planet for various reasons, some of them in the name of research, some as means of communication and connectivity and some for purposes the people who launched them would prefer that we do not know. More than half of those up there now are part of Musk’s Starlink project. The prospect is dismal for those trying to learn more about our universe and our solar system. Take, for instance, the Rubin Observatory, due to start its work in 2024 at a construction cost of $700-million (€663.2-million) which finds itself especially seriously threatened by what could be tens of thousands of orbiting satellites Scientific American explains: “The observatory’s planned Legacy Survey of Space and Time will use an 8.4-meter telescope combined with a 3.2-gigapixel digital camera—the largest ever built—to capture 1,000 images of the sky every night for a decade. Each image will cover 9.6 square degrees of sky, which is about 40 times the area of the full moon.” The intention is to track down near-Earth objects that could pose a threat, like the giant asteroid that put an end to the dinosaurs (except the birds) and to the cretaceous era. The observatories’ operators have warned that the rapid deployment of ever-more artificial satellites could “blind” the telescope, like the full beam headlights of oncoming cars when you’re driving at night. We could all be joining the ground-shaking sauropods and sharp-toothed theropods in eternal extinction. Archaeologists of the distant future may come across our remains and after decades of research conclude that we had become extinct because of our insatiable desire to talk to one other, or to watch television.