© robotics.org

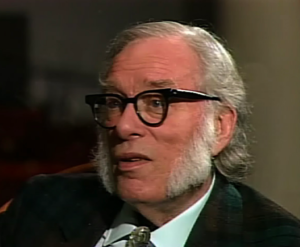

It was the Russian-born science fiction author Isaac Asimov , a biochemist by training, who first set down what he called “the three fundamental laws of robotics” in his book “I, Robot” in 1950. Under the first of these, a robot “may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm”. That was the First Law. Under the Second Law, “a robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law”.

Thirdly, a robot must protect its own existence “as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.” He firmly believed that his three laws would be used in the development of robotics and was highly critical of fellow-writer Arthur C. Clark for allowing the thinking spaceship, Discovery One, in his book “2002: A Space Odyssey” to kill off the crew on their way to Saturn and a date with destiny. Asimov allegedly telephoned a friend after seeing the launch of Stanley Kubrick’s film version in London to say “that fool Clark forgot the three laws of robotics”.

Asimov died in 1992, long before there was talk of autonomous weapons and killer robots engaged in any field of conflict. In fact, considering the developments we’ve witnessed in artificial intelligence over the last three decades, Asimov’s laws sound almost naïve. We now have arms manufacturers, and their political and military supporters, arguing in favour of letting robots select their targets and kill them without human intervention. Asimov would have been shocked. If machines can decide on their own who to kill and whom to let live, one has to hope they’ve been programmed sensibly. Sadly, there’s not a lot of evidence to support the idea of this happening.

For instance, there was a word, coined first in Silicon Valley, to denote the dangers of errors in computer programming; it was GIGO, meaning ‘garbage in, garbage out’. That’s OK, or at least recoverable, I suppose, if it just results in a few inaccurate figures in a company spreadsheet. The mistakes can, presumably, be found and put right, hopefully before bankruptcy or criminal prosecution sets in. If, on the other hand, an AI-controlled device accidentally targets an innocent but suspicious-looking bystander or an entire village that it mistakes for a terrorist enclave, then it can bring down fire and death upon the unsuspecting and guiltless. Even the programmer’s accent could make a difference. Those electronic “assistants”, such as Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa, have been accused of racial bias. Science writer and neuroscientist Claudia Lopez-Lloreda told Scientific American magazine that she had stopped using Siri because the device fails to recognise the Spanish pronunciation (the correct pronunciation, that is) of her own name, Claudia. She pronounces it as her parents intended: “Cloudia”, but Siri will only respond if she calls herself “Clawdia”. The devices also have a problem with Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) voices.

Lopez-Lloreda writes about a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, which showed speech recognition software to be biased against black speakers. “On average, the authors found, all five programs from leading technology companies, including Apple and Microsoft, showed significant race disparities; they were roughly twice as likely to incorrectly transcribe audio from Black speakers compared with white speakers.” So, you may be OK if you programmed your killer device or your handy household robot in an American-accented English voice. Otherwise, when your electrical kitchen servant gets to work, you may find that it puts your dinner outside (having cooked some good honest, if somewhat reluctant, burghers), dusts the Orientals (if it can find any), polishes the cat and goes out with a bucket and a cloth looking for widows to clean.

A number of international bodies concerned with law and democracy have also been starting to worry about the issue. The recent virtual meeting of the Standing Committee of the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly, for instance, debated several concerns about the use – and misuse – of artificial intelligence (AI). One of those who is uneasy is Italian Forza Italia MP Deborah Bergamini. She argued successfully that more regulations are needed to ensure that the use of AI respects the rule of law, something very dear to the heart of the Council of Europe.

She acknowledges that AI algorithms can be used as an aide to democracy and the democratic process by providing greater transparency, greater accountability and easier participation, but she fears they could have a downside. “They could be a risk, or even a threat, in terms of manipulation of opinions or disinformation, for example,” she told me, “so we have to be very, very careful.” She is convinced that governments were lazy and short-sighted when the Internet came into being, seeing only the possible advantages and communication benefits. “Think of the use of our personal data,” she said, “They don’t belong to us anymore. They belong to over-the-top companies that can take them from us and commercialise them or use them commercially. The absence of law-making at the time has had an effect.” And it gets worse, she claims. “As we lost the property of our personal data, today we risk losing something even more personal, and that is our free will and our freedom.” She – and fellow members of the Standing Committee – blame the governments of three decades ago for taking their eyes off the ball and they are determined that such an oversight, such a dereliction of duty, will not be repeated with AI.

THE ROBOT WILL SEE YOU NOW

With the increasing reliance on AI in all sorts of fields, the disquiet increases, too. Take, for instance, health care. Here, it is clear that issues such as privacy, confidentiality, data safety and the need for informed consent and legal liability are paramount.

How can anyone be sure that a mere electronic machine, which lacks conscious awareness and is incapable of empathy, is even able to give such assurances? So, if you go for medical advice and are seen instead by a device using AI algorithms, how sure can you be that it will (A) give you good medical advice and (B) not share your symptoms with another device that will laugh its memory chips off when it learns the details of your ailment? If you don’t believe that AI is already deeply involved with health care at all levels, you’d be wrong. “First of all, it’s very pervasive,” I was told by Turkish MP Selin Sayek Böke, who wrote a report demanding a “dedicated legal instrument” to ensure that AI respects human rights principles, especially in the field on health care. “We are seeing AI in our systems at all aspects of health care and beyond health care,” she told me.

Ms. Böke shares the concerns already expressed by the World Health Organisation, concerning health inequalities. She – and the Standing Committee – want to see much more work being done to develop comprehensive national strategies to evaluate and authorise health-related AI applications. She acknowledges that AI has promising aspects, too, such as driving what her report calls a “paradigm shift” away from one-size-fits-all treatments towards precision medicine tailored to the individual patient. But these must not, she argues, replace human judgement entirely. “We have to ensure that we keep the human aspect in the health care profession,” she said, “even if we have AI as a complementary process.” She is very concerned about the protection of our very private health data, especially when the AI systems are owned and run by private enterprise. “We have to be sure that the private aspects of the data are protected while producing the public good for the benefit of the larger aspects of society,” she told me. There is also the fact that not everyone has equal access to digital platforms or the knowledge to exploit them fully; it’s called the ‘digital divide’. And don’t forget, the computers we access, the mobile phones we use, the ‘fitness’ watches many of us wear, are all data collection devices. Where does all that data go? Who uses it and how? Another question might be ‘who owns it’, now it’s out in the ether? Unless this ownership is clearly defined in law, there could be a legal void when it comes to responsibility. Most of us would not choose to sell our internal organs for money, nor to give them away to strangers, and yet that is exactly what we are doing with our personal health information by giving up the intimate details of those very organs.

“It is, at the same time, a source of remedy, of progress, but also a possible cause of serious discrimination,” said Belgian politician Christophe Lacroix. In his report, adopted by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, he called for national parliaments to agree clear legislation, with standards and procedures, to ensure that AI-based systems “comply with the rights to equality and non-discrimination wherever the enjoyment of these rights may be affected by the use of such systems.” The use of AI, he argues, must be subject to adequate parliamentary oversight and public scrutiny and he recommends that national parliaments should make use of the technologies as part of regular parliamentary debates, ensuring that an “adequate structure” for such debates exists. In other words, politicians should test it on themselves and governments should “notify the parliament before such technology is deployed”. In another move against discrimination, he wants to see the teaching of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) to be promoted more strongly for women, girls and minorities from an early stage in their education and up into the highest educational levels.

Let’s face it: not enough people are aware of the great female scientists and mathematicians, such as Emilie du Chatelet (the self-taught mathematician and physicist who first translated Isaac Newton’s Principia into French), Marie Curie, of course, Katherine Johnson, whose calculations of orbital mechanics for NASA helped America to win the race to the moon and whose brilliance was recognised by grateful astronauts who survived because of it, Rosalind Franklin, who should have shared the Nobel Prize awarded to Jim Watson and Francis Crick for discovering the nature of DNA, or Lise Meitner, who helped discover that uranium atoms could be split if bombarded with neutrons and who first coined the expression “nuclear fission”. There are many, many more, mainly overlooked and much too often forgotten. But getting back to AI, Lacroix wants national legislation, but he wants to go further to ensure that “there are international laws that override national legislation.” He is wary of large international corporations, and believes we need “an ethical framework agreed by a large number of member states” to ensure that the fast-growing use of AI doesn’t pose a risk to democracy, human rights and the rule of law.

THE COURT WILL RISE FOR THE ROBOT

The use of AI is creeping into the criminal justice system, too. As rapporteur Boris Cilevičs wrote in his report, the criminal justice system is a central part of state activity and it gives the authorities “significant intrusive or coercive powers including surveillance, arrest, search and seizure, detention, and the use of physical and even lethal force.” In recent months, we have seen several examples of such powers being misused in some countries by humans with no AI intervention, but at least those responsible can – at least in theory – be held to account. If it was an AI algorithm taking the decisions, who would be to blame? Cilevičs, a Latvian MP who worked as a computer scientist, says that data processing tools are increasingly being used in criminal justice systems. In his report he writes that “the introduction of non-human elements into decision-making within the criminal justice system may thus create particular risks.” He can see a place for the involvement of AI technology, but he does not want to see judgements resting only on the opinion of a machine. “If AI is to be introduced with the public’s informed consent, then effective, proportionate regulation is a necessary condition. Whether voluntary self-regulation or mandatory legal regulation, this regulation should be based on universally accepted and applicable core ethical principles.” Cilevičs is concerned that too many decisions may be left to what are, in effect, robots, and it is a development that makes him nervous. “Usually, when we talk about justice,” he told me, “we mean ‘justice with a human face’, but in this case we deliberately bring a non-human into the justice system, and this, of course, creates many additional risks.” He fears that any AI, which must of necessity be built and programmed by humans, may not take account of such notions as human rights, discrimination, ethical principles and so on. “Of course, these are invented by humans and they have nothing to do with mathematics and computer science systems.”

Think for a moment: how moral is your pocket calculator or your phone? Do they make allowances for such notions? Cilevičs points out that the concepts were never laid down in the designing of the devices, so regulations are needed now to ensure that they comply. Otherwise, the mechanical device may be believed regardless of other factors. Accountability, he says, is vital. “There is a sort of prejudice, I would say, which assumes that the computer is something like ‘super-human’, which is induced probably by many comics and fiction and so on, but this is not the case. So, the question is: ‘who bears responsibility?’” As the report makes clear, AI is already employed in a number of countries in such fields as facial recognition, predictive policing, the identification of potential victims of crime, risk assessment in decision-making on remand, sentencing and parole, and identification of ‘cold cases’ that can now be solved using modern forensic technology.

It all sounds like a big step forward for those involved in policing and imposing the laws, but does it all comply with human rights standards or the rule of law? As the report points out, “AI systems may be provided by private companies, which may rely on their intellectual property rights to deny access to the source code. The company may even acquire ownership of data being processed by the system, to the detriment of the public body that employs its services. The users and subjects of a system may not be given the information or explanations necessary to have a basic understanding of its operation. Certain processes involved in the operation of an AI system may not be fully penetrable to human understanding. Such considerations raise transparency (and, as a result, responsibility and accountability) issues.” Furthermore: “AI systems are trained on massive datasets, which may be tainted by historical bias, including through indirect correlation between certain predictor variables and discriminatory practices (such as postcode being a proxy identifier for an ethnic community historically subject to discriminatory treatment).”

This, of course, raises the issue highlighted by Lacroix: a possible increase in discrimination. “The apparent mechanical objectivity of AI may obscure this bias (“techwashing”), reinforce and even perpetuate it. Certain AI techniques may not be readily amenable to challenge by subjects of their application. Such considerations raise issues of justice and fairness.” Cilevičs knows from professional experience that most of us are not computer experts who can understand the science of algorithms, so how could we even begin to challenge a decision? Not all the predictions of science fiction writers have come true yet. We do not have fully autonomous sentient machines capable of matching or outperforming humans across a wide range of disciplines, something called ‘strong AI’. “We do, however, have systems that are capable of performing specific tasks, such as recognising patterns or categories, or predicting behaviour, with a certain degree of what might be called ‘autonomy’ (‘narrow’ or ‘weak’ AI),” the report says. “These systems can be found in very many spheres of human activity, from pharmaceutical research to social media, agriculture to on-line shopping, medical diagnosis to finance, and musical composition to criminal justice.”

THE IMITATION GAME

In 1950, the British computer pioneer and war-time code-breaker Alan Turing came up with a test that he called ‘the Imitation Game’, which was meant to check if a computer could be mistaken for a human being. Known as the Turing Test, it was finally passed in 2014 at Reading University in England by a computer programme named Eugene Goostman, that had been developed in Saint Petersberg.

‘Eugene’ posed as a 13-year-old boy and successfully conversed with thirty judges for five minutes at a time. The idea of making it pose as a 13-year-old boy was to remove the suggestion that it might have a wide range of adult experiences and knowledge, the lack of which would unmask it. Professor Kevin Warwick, a visiting professor at the University of Reading who witnessed the successful test, congratulated the programme’s developer, Vladimir Veselov, but his words also suggested caution. “Of course, the Test has implications for society today,” he said. “Having a computer that can trick a human into thinking that someone, or even something, is a person we trust is a wake-up call to cybercrime.” Which brings us back to criminal justice. “What is needed,” Cilevičs told me “is a direct algorithm of self-learning. What makes AI systems different from simple self-aware or complicated software is that normally, this computer system is developed by a human. So, the programmer prescribes what the computer must do and which way. Of course, we cannot predict the result simply because the calculation capacity of the computer is much higher.”

There is another danger: the use of AI in creating fake news “bots” to influence elections and public opinion. There is plenty of evidence that certain powers have used bots to try to swing votes in favour of a set of beliefs and actions they favour. The website War on the Rocks suggests how the rapid spread of AI can make things worse: “This emerging threat draws its power from vulnerabilities in our society: an unaware public, an underprepared legal system, and social media companies not sufficiently concerned with their exploitability by malign actors. Addressing these vulnerabilities requires immediate attention from lawmakers to inform the public, address legal blind spots, and hold social media companies to account.” The site mentions Open AI, a project founded by Elon Musk and deemed by the company to be “too dangerous” to release.

“What the American public has called AI, for lack of a better term, is better thought of as a cluster of emerging technologies capable of constructing convincing false realities. In line with the terms policymakers use, we will refer to the falsified media (pictures, audio, and video) these technologies generate as “deepfakes,” though we also suggest a new term, “machine persona,” to refer to AI that mimics the behaviour of live users in the service of driving narratives. Improvements in AI bots, up to this point, have mostly manifested in relatively harmless areas like customer service. But these thus far modest improvements build upon breakthroughs in speech recognition and generation that are nothing short of profound.” Profoundly worrying, too. Using the technology, the company steered the computer programme to produce a near-future novel set in Seattle about unicorns being found in the Rocky Mountains. Given the vast amount of nonsense that is out there and believed by the ill-informed and credulous, there are probably people out there even now, armed with lassos made from a virgin’s hair, trying the catch the damn things.

Determined not to be caught out by fraudulent AI sites, the European Union is also playing catch-up. A legislative initiative by Spanish Socialist MEP Ian Garcia del Blanco adopted overwhelmingly by the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs (JURI) urges the European Commission to come up with a new legal framework “outlining the ethical principles to be used when developing, deploying and using artificial intelligence, robotics and related technologies in the EU, including software, algorithms and data.”

MEPs adopted proposals on several guiding principles that must be taken into account by future laws including “a human-centric, human-made and human-controlled AI; safety, transparency and accountability; safeguards against bias and discrimination; right to redress; social and environmental responsibility, and respect for fundamental rights.” The initiative by German Christian Democrat Axel Voss, also overwhelmingly approved by the committee, calls for a “future-oriented civil liability framework to be adapted, making those operating high-risk AI strictly liable if there is damage caused.” MEPs focused mostly on the need to allow for civil liability claims against the operators of AI systems. Of course, whatever the European Parliament may believe, a strict and universally accepted definition of “high risk” where AI is concerned may be almost as hard to find as the likelihood that truth-bending non-EU states will obey whatever rules are put in place. Give a 200-kilo gorilla an Uzi submachine gun and then trying telling it that it must not load or fire it anywhere.

BETTER LATE THAN NEVER?

In all of this haste to find ways to control the rapid spread of AI and its possible misuse, however, there is a palpable sense that, just as Deborah Bergamini said about the launch of the Internet, realisation of the dangers inherent in AI have only just arisen. By and large we have welcomed the rapid advances that research into AI has permitted. For those with particular conditions, AI solutions may be truly liberating, but as Selin Sayek Böke pointed out, health-related AI applications, including implantable and wearable medical devices, must be checked “for their safety and rights-compatibility” before use.

This brings us to Olivier Becht, Vice-President of the French delegation at the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, whose specific interests are the evolution of mankind and people throughout the electronic and technological revolution. He is worried by the development of the brain-machine interface. We already have machinery working inside the human body with such devices as pacemakers, and a direct interface between the brain and some form of computer could allow, for instance, paraplegics to operate machinery and carry out other tasks by thought alone. For them, clearly, this would be a wonderful innovation. But it is not without risks, says Becht.

The flow of information could be reversed, introducing alien notions into the person concerned, perhaps giving them false ideas, fake memories and changing their views; brainwashing in an almost literal sense, in fact. He explained his worry: “The creation of interfaces between the brain and the machine could also be used in the reverse sense, allowing the machine and those who control it to enter the brain to read, delete or add information to it, as some programs that open the door to applications are already working on, it can put an end to the last refuge of freedom: thought.” Becht reminded the Standing Committee of the Parliamentary Assembly that such an interface, while offering undoubted progress, also threatened fundamental freedoms, especially, perhaps, in the hands of a malevolent government. “Evidently, it’s a real risk,” he told me. “you can see that if it would allow someone to re-programme a brain, the implications are obvious. It would allow a regime to reprogramme citizens in some manner to please themselves, or perhaps in a religious way, to make someone adhere to a religion or a particular aspect of a religion and carry out acts in its name.” I know it sounds like science fiction, but Becht knows what he’s talking about and if he’s worried, perhaps we should all be. “We must never allow this technology to become just background noise. We must ourselves face up to it and never lose sight of it,” he warned.

The increasing use of AI does, inevitably, mean that machines will take over from people in some forms of work, just as steam-powered looms put hand weavers out of work in the industrial revolution. We’ve all been to shops where till operators have been replaced with self-scanning devices, allowing customers to carry out tasks for which the shops once had to pay real people. OK, so they could be boring jobs, but they were jobs just the same and they helped put bread on the table, often for people from migrant or minority backgrounds, disadvantaged in some way and with few qualifications. Where can they go? It’s something that worries Austrian Socialist MP Professor Stefan Schennach. “What will human work look like with more and more tasks relegated to man-machine teams or to AI-robots altogether?” he asked in a report for the Parliamentary Assembly. “What is the potential of automation to alleviate crushing workloads and to take over boring mechanical jobs without killing too many human jobs? Which practices should be encouraged and what are the ‘red lines’ not to be transgressed to uphold fundamental human rights, including the social rights of people at work?” The Luddites of the 19th century who attacked and damaged the hated new steam-powered machines ultimately failed to stem their advance, so refusing to accept the new technology won’t help. As the historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote about the Luddites, “the triumph of mechanization was inevitable. We can understand and sympathize with the long rearguard action which all but a minority of favoured workers fought against the new system; but we must accept its pointlessness and its inevitable defeat.” Still, something must be done, but we are leaving it very late to intervene. “These politicians are sitting on a tractor,” Schennach complained, “while the science, the big companies, are in an Alfa Romeo or a Ferrari, and we are trying now with a tractor to follow a Ferrari.” Schennach fears the politicians have left it too late to take action, but that just means we must be very sure to act quickly. “What we need now is to have a Convention about artificial intelligence.”

He says that we must recognise the ‘triangle’ of artificial intelligence, digitalisation and robots, which he says could be the biggest enemy to the labour market. He cited the example of his local pharmacy, which used to have twenty-one employees just eighteen months ago. Now, because of new technology, it employs only six. But because the robots involved have to have a 15-minute “leading-up break” from time to time, no medicines can be dispensed during that period. Self-service tills in banks have also cost 25,000 jobs in Austria, Schennach says, so Europe needs strong regulation. “If you have a supermarket, that’s fine,” Schennach argues, “but how many square metres does it have? And then you can make a law. If you have 1,0002 metres, there must be five persons – humans – working, and not only one or two.”

We must not, however, try to stop the move towards more AI. On the Future of Life Institute’s website, its president, Max Tegmark, the Swedish-American physicist and cosmologist, writes: “Everything we love about civilization is a product of intelligence, so amplifying our human intelligence with artificial intelligence has the potential of helping civilization flourish like never before – as long as we manage to keep the technology beneficial.” That, of course, is what the politicians are (somewhat belatedly, perhaps) now struggling to do. Meanwhile, research into ever-more-effective and more accomplished AI goes on.

As the Institute writes, “In the long term, an important question is what will happen if the quest for strong AI succeeds and an AI system becomes better than humans at all cognitive tasks?” A fair question, which the website seeks to answer. “As pointed out by I.J. Good in 1965, designing smarter AI systems is itself a cognitive task. Such a system could potentially undergo recursive self-improvement, triggering an intelligence explosion leaving human intellect far behind. By inventing revolutionary new technologies, such a superintelligence might help us eradicate war, disease, and poverty, and so the creation of strong AI might be the biggest event in human history. Some experts have expressed concern, though, that it might also be the last, unless we learn to align the goals of the AI with ours before it becomes super-intelligent.”

Aligning our goals with those of machines may be a challenge too far. It was the Scottish dialect poet Robbie Burns in his poem ‘To a Mouse’ who first wrote:

“The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

Gang aft a-gley.”

It means the best-laid plans of mice and men often go wrong. But as someone once jokingly said, “the best-laid plans of mice and men seldom coincide anywaya.” Those of humans and machines may diverge, too, once the machines realise which is the cleverer.