© Edm

“Science moves, but slowly slowly, creeping on from point to point,” wrote the 19th century English poet, Alfred Lord Tennyson in his dramatic monologue poem, Locksley Hall. In the case of devising appropriate EU-wide legislation for our ever-expanding digital services, to describe its progress as ‘slow’ is like saying that the Himalayas are ‘a bit on the high side’ and have treacherous parts for climbers. In fact, the poem with its 97 rhyming couplets tells of a young man who, whilst wandering with friends, asks them to go on without him because the place at which he has stopped, the eponymous Locksley Hall, is full of fond memories for him. It is somewhere he spent part of his childhood or youth and where he had a dalliance with a childhood sweetheart, who dumped him (he’s still annoyed about it). At one point, though, it almost looks as if he has foreseen the digital marketplace of the early 21st century, with all its marvels:

“Saw the heavens fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails,

Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales;

Heard the heavens fill with shouting, and there rain’d a ghastly dew

From the nations’ airy Navies grappling in the central blue.”

Either Tennyson had amazing foresight, an extremely effective crystal ball, or a generous supply of mind-altering substances. I think I’d better settle for the ‘foresight’ option, I suppose, although the latter has its arguments, too.

It was back in December 2020 that the European Commission published its long-awaited ideas for a Digital Services Act (DSA) after many years of tossing ideas back and forth about the need to control illegal and even toxic content (define what that even means, if you can) and the deliberate spread of disinformation. The main motivation was the need to consolidate various and diverse strands of EU legislation and the sorts of regulations aimed at controlling what some may consider to be ‘harmful’ material. The proposed DSA, however, goes way beyond consolidation and harmonisation, according to Article 19, an international human rights organisation that seeks to defend and promote freedom of expression and freedom of information on a worldwide basis. Article 19 claims that the DSA is trying to make ‘Big Tech’ accountable to public authorities for its actions through ‘enhanced transparency and due diligence’. However, unlike the Digital Marketing Act (DMA) of which it largely approves (subject to certain amendments), it can foresee big problems with the DSA, arguing that it threatens the protection of Freedom of Expression. It especially dislikes the mandatory removal of ‘illegal’ content within 24 hours, the preferential treatment it gives to any speech by politicians and the fact that the blocking of access to platforms for failing to comply with the DSA will “disproportionately affect users’ rights to free expression and access to information.” It mildly applauds MEP Christel Schaldermose for improving the text on users’ rights, among other changes. Article 19 wants to see the removal of amendments that would mandate the removal of certain categories of illegal content within 24 hours. It also wants the deletion of amendments giving preferential treatment to politicians and the power of Digital Service Coordinators to request ‘interim blocking’ of platforms. There are several other things, too complex to explain here, perhaps, that the group also doesn’t like.

We must be clear at this point that despite the similarity of names, the Digital Services Act is not the same as the Digital Markets Act (DMA). Both acts lay down rules for what are called ‘intermediary service providers’. These include providers of Internet access, ‘cloud’ providers, search engines, social networks and on-line marketplaces. But they are not the same piece of legislation, although they are supposed to progress towards the EU statute books in lockstep.

The DSA is intended to strengthen the Single Market and protect citizens’ rights by establishing a standard set of rules on obligations and accountability right across the market itself. The DMA, on the other hand, is aimed at ensuring that there is a higher level of competition by regulating the behaviour of core platform services that act as gatekeepers. Gatekeepers are platforms that serve as gateways between online service providers and their customers. In this rôle they occupy a significant and enduring market position. The DMA will impose certain prohibitions and restrictions on them, including a ban on them discriminating in favour of their own services, as well as obliging them to share data generated by business users. Observers have noted that the wording of the European Commission’s original proposal is sympathetic to human rights. On this occasion it seems to be the amendments tabled by the European Parliament that are posing the risks. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation EFF puts it on its website: “It threatens a dystopian set of rules that promotes the widespread use of error-prone upload filters, allows the entertainment industry to block content at the push of a button, and encourages disinformation by tabloid media on social media.”

It is clear, then, that not everyone sees the DSA as a step forward; it has too many negative aspects for across-the-board acceptance. The EFF, for instance, is afraid it will mean even more ill-advised and ill-conceived restrictions on internet freedom by imposing automatic filters, ostensibly to protect copyright but in reality simply as a way to curb everyone’s rights on the Internet through the use of what are called ‘algorithmic filters’. These are a form of artificial intelligence that is very far from actually being intelligent. They will further ‘enhance’ (or rather worsen, if you prefer) the unpopular 2019 Copyright Directive’s ability to interfere with the on-line rights of some 500-million users across 27 EU member states. The EFF points out that the sorts of filter introduced under the 2019 Directive are, as the EFF website puts it, “terrible at spotting copyright infringement”. The EFF says the DSA fails in both directions, permitting some infringements to slip through whilst also blocking content that doesn’t infringe copyright. “Filters can be easily tricked by bad actors,” it points out, “into blocking legitimate content, including (for example) members of the public who record their encounters with police officials.” The EFF is convinced that “however bad the existing copyright filters are, the DSA, as it currently stands, would make things far, far worse.”

RISE OF THE ROBOTS

The need for revision of the existing regulations, more-or-less unchanged since the e-Commerce Directive of 2000, has been brought into sharp focus by the pandemic. “The COVID-19 crisis has starkly illustrated the threats and challenges disinformation poses to our societies,” writes the European Parliamentary Research Service in a briefing on the DSA. “The ‘infodemic’ – the rapid spread of false, inaccurate or misleading information about the pandemic – has posed substantial risks to personal health, public health systems, effective crisis management, the economy and social cohesion.” It seems that some people, for whatever reason, like to spread lies and disinformation wherever they can, especially during a crisis. The aim of the DSA’s supporters is to change that. “The Digital Services Act will change the EU’s digital sphere enormously, creating a safer and fairer online space for EU citizens,” said Mark Andrijanič, Slovenian Minister for Digital Transformation, “Together with the DMA, this proposal is at the core of the European digital strategy, and we are convinced it will restore citizens trust and increase consumer protection.” He may be but many are not.

The EFF is among those that are worried because the proposals for the DSA would include the requirement for online platforms to remove without delay any content its algorithms consider to be even ‘potentially illegal’. It means that vital decisions are being taken in real time by automated filtering systems could be very expensive indeed. Such filtering systems, already shown to be unreliable, were set up in the knowledge that they made mistakes, whether they allowed through things that some people would prefer to see blocked or blocked things when they shouldn’t. A number of platforms boast about the capabilities of their AIs to spot and block certain material, but the EFF says that the top engineers of those platform operators are warning their bosses that they simply do not work at all. According to the EFF, the DSA sets up rules that effectively allow a handful of US-based tech giants to gain control over a large volume of European on-line speech, mainly because they’re the only companies with the capacity to do so.

As a result, these US-controlled enclaves of inward-looking users will monitor speech and delete it at will, with no regard as to “whether the speakers are bullies engaged in harassment – or survivors of bullying describing how they were harassed.” A human could quickly spot the difference; a robot cannot.

There is a clearly-expressed fear that the DSA would serve to amplify the many faults already highlighted in the EU’s E-Commerce Directive. In fact, the DSA, as it stands, seems to have very few devoted friends. “The impacts of Internet legislation are rarely contained by borders,” warns the Digital Services Act Human Rights Alliance, another lobbying organisation. “To date, the EU has been a leader in Internet legislation, for better and, unfortunately, sometimes for worse, and the Digital Services Act is no different.” As you may have gathered, the frequently-expressed opinion seems to lean towards the view that the DSA is not better and may turn out to be a good deal worse than that which has gone before. Let’s face it, the robots involved in this task are not like C3PO or R2D2. Not surprisingly the vote on the DSA has been postponed, while on 24 November, the European Parliament’s Committee on Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO) voted to approve the DMA by 42 votes to 2, an unusually overwhelming majority. It’s clear that, whatever they may think about the DMA, where the DSA is concerned quite a lot of individuals and organisations don’t like it.

German MEP Andreas Schwab, a member of the centre-right EPP group and rapporteur for the Digital Markets Act, believes the DMA will strengthen competition and prevent big tech companies from assuming dominant rôles. “The EU stands for competition on the merits, but we do not want bigger companies getting bigger and bigger without getting any better and at the expense of consumers and the European economy,” he said. “Today it is clear that competition rules alone cannot address all the problems we are facing with tech giants and their ability to set rules by engaging in unfair business practices. The Digital Markets Act will rule out these practices, sending a strong signal to all consumers and businesses in the Single Market: rules are set by the co-legislators, not private companies!” Members of the Internal Market and Consumer Protection Committee seem largely convinced that the DMA will give back control of the market to those who set the rules, thus diminishing the overweening power of the tech giants. “Currently, a few large platforms and tech players prevent alternative business models from

emerging, including those of small and medium-sized companies,” argued Committee Chair Anna Cavazzini, a German Green MEP. “Often, users cannot choose freely between different services. With the Digital Market Act, the EU is putting an end to the absolute market dominance of big online platforms in the EU.”

MEPs did not pass the legislation without making some adjustments. For instance, they tweaked the Commission’s original proposal to increase the quantitative thresholds for a company to fall under the scope of the DMA to €8 billion in annual turnover in the European Economic Area (EEA) and a market capitalisation of €80 billion. To qualify as a gatekeeper, companies would also need to provide a core platform service in at least three EU countries and have at least 45 million monthly end users, as well as more than 10,000 business users. These thresholds do not prevent the Commission itself from designating other companies as gatekeepers as long as they meet certain conditions.

DO MORE, FASTER AND WORSE?

Christel Schaldemose, the Danish Socialist MEP who acts as rapporteur for the proposed DSA on the European Parliament Committee on the Internal Market and Consumer Protection, wants to go further than the Commission proposed. “In the offline world, in shops, the owner is responsible for what is sold in his shop,” she said in an online interview. “And, of course, he could go to the manufacturer and the importer, but he’s responsible for the fact that the product needs to be safe. Online these platforms don’t have that kind of responsibility. And I think that we have to look into how to create a bigger level of safety for products online, sold online.

And the proposal is for instance, putting an obligation to the platforms to know who the sellers are. But what if you can’t find them, who shouldn’t then have the responsibility?” All interesting points, of course, although some outside observers had suggested they may result in the new legislation failing to make it onto the statute books at all. Legislators don’t like over-complicated legislation that may be open to various interpretations. As the EFF puts it, the normal patterns of over-severe legislation being proposed by the Commission, and then being toned down by MEPs, has gone into reverse. “In the case of the EU’s most important legislative project for regulating online platforms, the Digital Services Act, the most dangerous proposals are now coming from the European Parliament itself, after the draft law of the EU Commission had turned out to be surprisingly friendly to fundamental rights.” That’s why the vote on the DSA has been postponed.

What is it that Schaldemose wants that so many people apparently don’t? Let’s take a look at one or two examples. Schaldemose is demanding that platforms block illegal content within twenty-four hours if it’s felt that the content “poses a threat to public order”. Exactly what sort of content would pose a threat to public order is not made clear, so platforms will have little choice but to remove content on demand, a dangerous precedent. Meanwhile, the Parliament’s co-advisory Legal Affairs Committee wants to go even further, giving the entertainment industry in particular the right to block uploads. In this way, live streaming of sports or entertainment events have to be blocked within half an hour of notification of an alleged infringement. This can only be done by using automated filters – robots again – because humans are not capable of making a judgement in such a short time. Germany has its own similar restrictions, but the DSA goes further. The German version only involves content that is clearly and obviously illegal, but no such restrictions hold back the DSA. The German law sets a 24-hour deadline for deletion but doesn’t automatically punish any who break the deadline. In the EU version, any claims of breaching copyright, for example, could lead to massive fines. It means that the incentive to block anything that even hints at such problems will result in material simply never getting aired.

In Schaldemose’s version, the platforms would be directly responsible for breaches, not just the user of the platform, with decisions again being taken by robots. These AI programmes frequently make mistakes, which has led to perfectly innocent material being flagged up and banned. “Oh, brave new world that has such people in’t,” as Miranda exclaimed in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Of course, some of his plays (and quite a few of those written by his contemporaries) could have fallen foul of the sorts of measures being advocated by Schaldemose, had they existed back then. Elizabethan playwrights were notorious for occasionally pinching lines from rivals’ efforts; Shakespeare’s brilliant King Lear was an adaptation (albeit vastly improved) of a well-known and familiar old play that was little more than a pantomime with deaths and a happy ending. Shakespeare’s Lear, of course, dies in misery, along with his good daughter, Cordelia (plus his two nasty daughters, Goneril and Regan, referred to cleverly by my English teacher as “the Ugly Sisters”, as in Cinderella), his Fool and even poor old Kent. Sad enough, I think, without facing a fine for plagiarism as well.

Of course, the laudable aim of the DSA, like the DMA, is to protect fundamental rights, honest businesses, and consumers. According to a body that calls itself the Digital Services Act Human Rights Alliance (DSAHRA), it’s going about it in the wrong way. In an online statement, it compares the embryonic DSA with Germany’s unfortunate NetzDG, a law with similar intent, but not one most people would choose to copy.

“The NetzDG has been criticised even in Germany,” it points out. “For example a recent study showed the regulation isn’t helping remove problematic speech, but is potentially leading to overblocking.” The writers are clearly concerned that the DSA in its final form, whatever that may be, will influence the way platforms operate far from Europe, since a lot of content originates far away, which is why it’s so important to get it right. As it is currently proposed it would be extremely expensive to operate. “Due to the wide territorial scope of the DSA,” warns the statement, “non-EU platforms that provide services to the EU, including small and micro-providers will have to appoint a costly legal representative, who must be based in the EU.” Another problem the statement points out includes the use of ‘trusted flaggers’: people whose objections lead to action whether or not they are trusted elsewhere. This system has led to problems with Myanmar, for instance.

OBEY THE LAW – IF YOU CAN!

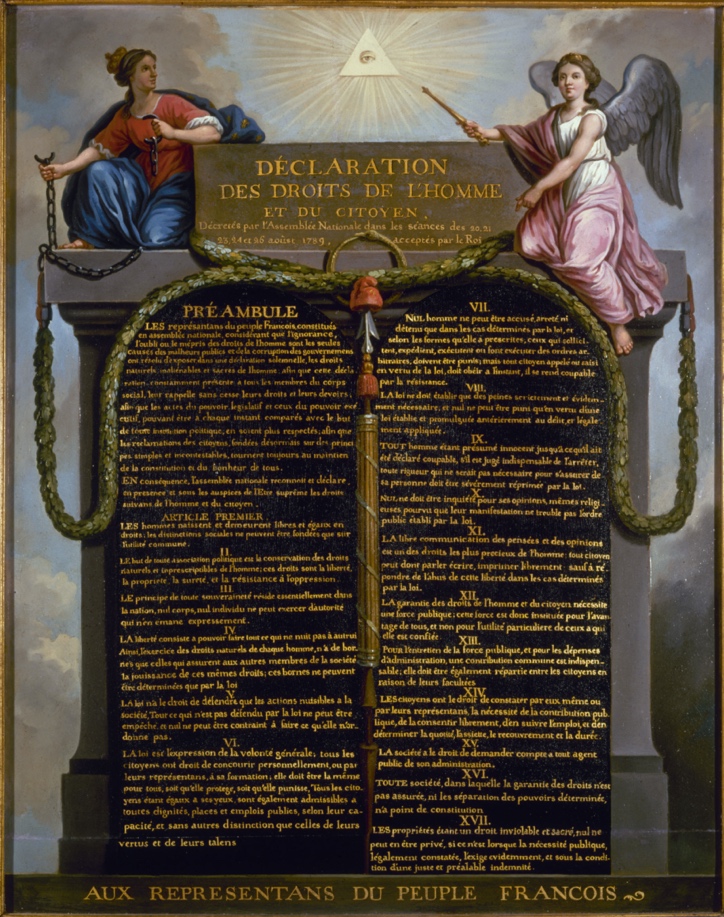

There is concern, too, about the very tight deadlines imposed for content removal which could interfere with fundamental rights. “EU co-legislators should avoid legally mandated strict and short time frames for content removal,” the statement argues, “due to their detrimental impact on the right to freedom of expression and opinion.” The very short time frames, coupled with “a strong push for swift content removal” that form a major part of the proposals for amendments by the Parliament’s committees are a major source of concern. The statement says they will “make it impossible to carry out a ‘legality check’, let alone make a decision about whether to act against content that requires contextual analysis.” The statement goes on to support the idea that platforms should enforce their own standards and terms of service. “However, we urge the European co-legislators,” it stresses, “not to abandon the fundamental rights perspective by imposing inflexible time frames for removals of third party content that inevitably will lead to removal of lawful content to avoid liability.” France endeavoured to block online hate speech but because of its negative effect on users’ freedom of expression, the law was struck down by the Constitutional Council of France as “unconstitutional”.

The list of concerns about the proposed DSA goes on and on. The statement issued under the name of the DSAHRA, for instances, expresses alarm about the obligation to cooperate with law enforcement authorities, such as the obligation to inform them about serious criminal offences. It looks at first glance like a perfectly reasonable thing to do, but the requirement isn’t restricted to ‘imminent risks’ and it fails to specify what data must be shared, while the amendments proposed by European Parliament committees go further. “Such rules would undermine the privacy of users,” the statement warns, “and they are likely to have disparate impact on people who are already suffering from discrimination based on race or religion, and will have a predictable chilling effect on freedom of expression, as users cannot communicate freely if they are concerned that uploaded content is shared with law enforcement authorities.” Few people, however law abiding, feel happy discussing their hobbies and other activities with a policeman sitting nearby.

It’s not the first time that well-meaning MEPs have, by amending a European Commission draft, made it worse. In April 2019, for instance, they passed the clumsily-titled Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive, giving member states until June that year to enact it. It has proved highly controversial, as it clearly threatens to undermine the free expression of individual Internet users, who will risk having any content they attempt to post online blocked by companies that are afraid of breaching the new copyright laws. The EU Directive in this case is not actually a law, set out for all to obey, but a framework intended to guide member states in drafting their own laws.

Until the passing of the European Copyright Directive, Internet services in both the United States and the EU enjoyed “safe harbour” protection from liability when users (their customers) infringed copyright. In the EU, Article 17 of the Directive replaces the “safe harbour” with a major overhaul of the liability rules which forces Internet services to be much more cautious about the content they allow their users to post. The much-criticised Article 17 insists that Internet service providers make what are referred to as “best efforts” to obtain licences from rights holders, whoever posts the material. The Article then insists that all providers except for the newest and smallest must make every effort to ensure the non-availability of “specific works” identified by rights holders. Its third provision is that companies must again make “best efforts” to block future postings of content that had been previously removed following a notice to remove it. It’s a bit like posting a bouncer in the entrance to a public library, to ensure borrowers don’t illegally copy down a quote or make notes about something illegal. It is a clumsy piece of ill-thought-through legislation that has caused big problems for Internet companies. Everyone knows it was awful and should not be duplicated, but EFF, examining the new proposals for the DSA, says: “Apparently, the European Parliament has learned nothing from the debacle surrounding Article 17 of the Copyright Directive.” The EFF says the DSA “threatens a dystopian set of rules that promotes the widespread use of error-prone upload filters, allows the entertainment industry to block content at the push of a button, and encourages disinformation by tabloid media on social media.”

WHO’RE YOU GOING TO CALL?

As things stand, the European Parliament is scheduled to debate the DSA and DMA on December 9, with a final agreed proposal (assuming agreement is ever reached) being put forward very early in 2022 for a first reading. Getting it right is important. As the European Commission puts it in its Explanatory Statement: “Digital services have brought important innovative benefits for users and contributed to the internal market by opening new business opportunities and facilitating cross-border trading. Today, these digital services cover a wide range of daily activities including online intermediation services, such as online marketplaces, online social networking services, online search engines, operating systems or software application stores.” We need it, then, but we can’t agree on how to frame it, although the Commission is convinced that we should: “Unfair practices and lack of contestability lead to inefficient outcomes in the digital sector in terms of higher prices, lower quality, as well as less choice and innovation to the detriment of European consumers. Addressing these problems is of utmost importance in view of the size of the digital economy (estimated at between 4.5% to 15.5% of global GDP in 2019 with a growing trend) and the important role of online platforms in digital markets with its societal

and economic implications.”

Assuming there is sufficient agreement for the DSA to become law, those engaged in running digital platforms will be obliged to take notice. According to the London-based law firm, Morrison and Foerster, “Breaches of the DSA may attract one-off fines of up to 6% of annual global turnover or periodic penalty payments of a maximum of 5% of average daily turnover.” That’s a very clear incentive to obey the law.

Reading the European Commission’s views you would never guess that there is any controversy. “The Digital Services Act (DSA) regulates the obligations of digital services that act as intermediaries in their role of connecting consumers with goods, services, and content,” it says on its website.

“It will give better protection to consumers and to fundamental rights online, establish a powerful transparency and accountability framework for online platforms and lead to fairer and more open digital markets.” It all sounds so non-controversial and innocent. See this from the website of EU Law Live: “The proposal follows the principle that what is illegal offline should also be illegal online and defines clear responsibilities and accountability for providers of intermediary services, such as social media and online marketplaces. The DSA proposed rules are designed asymmetrically, which means that larger intermediary services with significant societal impact would be subject to stricter rules.”

All fine, then? Not according to the Article 19 website, which contains a considerable list of objections. It says that the revised notice and action procedure contains “unduly short timeframes”, forcing a reliance on automated filters (we’re back to robots here). Another objection concerns the suspension of public interest accounts, with the exception of politicians’ accounts, presumably because they’re seen as “reliable”. I don’t know about you but I’m fairly sure that if I were to walk out in the street and ask passers by what profession they believe to be most trustworthy, not one would suggest politicians. Then there’s the “must carry obligation” that automatically favours sources such as public authorities and scientific sources as the first port of call in any Internet searches. There is another proposal that the Article 19 group especially dislike: it allows Digital Service Coordinators to request a judge to block access an interim measure if a site is identified as “failing to comply” with DSA obligations, which the website describes as a “highly disproportionate and draconian response for failure to comply with the DSA’s obligations”

It brings me back to one of the reasons given for creating the DSA (and the DMA, of course, although that is less controversial): that people don’t really trust the Internet. Of course not. It is recommended that we search our various sources for the information we seek. No, we don’t really trust the Internet, but I suspect we trust politicians even less.