Central, Hong Kong as seen from Victoria Peak © Wikicommons

There is an old Chinese saying: “A closed mind is like a closed book; just a block of wood.” There can be few minds more closed, at least on some issues, than that of Xi Jinping, it seems. You will recall what Xi’s predecessor, Deng Ziaoping, proposed as a solution for Hong Kong’s future? It was “One country, two systems”. Deng was a visionary figure in many ways. Often referred to by his nick-name of Xixian, he was a revolutionary, a military commander and also supreme leader of the People’s Republic of China from December 1978 to 1992. His career showed an impressively upward rise to prominence. During the 1950s, he became Vice-Premier of the People’s Republic and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), although he was then considered a pariah during the infamous Cultural Revolution. He was brought back into the party fold by Zhou Enlai, but then booted out again by the so-called “Gang of Four”. When Mao himself died later that same year, there was a big power struggle and the members of the Gang of Four were arrested and Deng was reinstated. It was Deng who led his country out of the terrible, bloody mess left behind by the horribly misguided Cultural Revolution. He was, however, kicked out of the government following what happened in Tiananmen Square, although he continued to be an important influence until his death. His market reforms transformed China into the economic powerhouse it is today and earned him the title “architect of modern China”.

A confirmed Maoist, he will long be remembered as the man whose ideas had made China the world’s largest economy by 2010. Deng undoubtedly really meant “one country, two systems”, with Hong Kong in mind, but there is certainly no sign that the current leader, Xi Jinping, shares that view, or, perhaps, that he interprets it in the same way.

Deng proposed his solution back in the early 1980s, when he was Paramount Leader of China, engaged in negotiations with the United Kingdom about Hong Kong’s future. The bigger question now is not so much “does Hong Kong even have a future” (it obviously has) as “who will be in charge to guide it?” and probably “in which direction will it go?”. And will any of its current residents stay on if Beijing takes over completely? Remember, when Deng set out his plan for the future governance of Hong Kong and Macau, it was before they became redesignated as “regions” of China, Hong Kong in 1997 and Macau two years later. Xi seems to believe in one country, but apparently not ‘two systems’, unless it’s a simple choice: ‘my way’ or ‘not at all’. In fact, in respect of Hong Kong, Xi begins to look like that block of wood I spoke about. With him there can be no ‘halfway house’, no compromise. Under his rule, another well-known Chinese saying was proved wrong: “Clear conscience never fears midnight knocking.” Under Xi, no-one can relax when they hear a knock on the door at midnight. Xi likes to keep the Chinese people on their toes, it seems, as if fear of him and his soldiers equates to love of the leader. It doesn’t, and another old Chinese saying comes to mind: “Respect out of fear is never genuine; reverence out of respect is never false.” Xi seems not to subscribe to that doctrine, either. Deng’s approach was pragmatic and practical, but not what Mao’s most ardent supporters wanted to hear. Deng had stressed the idea of opening China up to the outside world. He believed in the ‘one country, two systems’ plan but wanted to see it implemented fully, not used as a blackout curtain to hide what was really happening. His was a pragmatic approach, not buried under the political dogma.

One of the problems is that Xi Jinping’s definition of democracy doesn’t match the predominant western version, although it probably finds favour among the world’s more ruthless despots. In the 1871 children’s book, “Through the Looking Glass” by Lewis Carroll, which brings back the Alice character of “Alice in Wonderland” fame, Humpty Dumpty tells Alice, “When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.” Alice asks how one word can have a lot of different meanings for different people and Humpty Dumpty replies: “The question is, which is to be master – that’s all.” Xi Jinping clearly has no problem with that. In China, he is the unquestioned master, and his meanings are his own, whatever he chooses them to be. Disagree with them at your peril! He still claims that “democracy is the key tenet unswervingly upheld by the Chinese Communist Party.” If you believe that, just trying telling the Chinese Communist Party that it has got something wrong. So when he told a conference audience that “true democracy” only began in Hong Kong when China took control, he really meant it, or at least believes it to be true. “After its return to the motherland,” he said, “Hong Kong compatriots became masters of their own affairs.” Many probably thought they already were.

This, of course, fell far short of what many in his audience (at home and around the world) may have wanted to hear, but Xi knows exactly what he means, even if few others are sure. “Hong Kong people administered Hong Kong with a high degree of autonomy, and that was the beginning of true democracy in Hong Kong,” he said.

That is clearly very different from the definition given by Abraham Lincoln in 1858, not long after the American Civil War. He told his audience: “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.” I can imagine some interesting but probably ill-tempered conversations in the next life (if there is one) between Xi and Abe. As for whether or not Hong Kong’s version of democracy would suit Abe Lincoln, I can only quote CNN World’s comment on the sweeping national security law imposed after 2020’s anti-government protests: “Two years later, no opposition lawmakers remain in the Hong Kong legislature, while nearly all of its leading pro-democracy figures, including activists and politicians, have either been forced into exile or imprisoned – with dozens of them behind bars.” No, I don’t think Xi and Abe would find much common ground when debating what democracy actually means, do you?

HOW DID WE GET HERE FROM THERE?

There is ample archaeological evidence that people lived in Hong Kong and the surrounding small islands during what was, in the West, the neolithic age, with burial sites containing skeletons from at least 3,000 BCE or earlier. Whoever they were, those inhabitants were followed by the Yue people, who were fully independent of outside control until the island was invaded by Qin dynasty forces from the rest of China. Various others took control for short periods, then in 111 BCE, the Han dynasty took over. Later, under the Tang dynasty, Hong Kong became famous for salt production and pearls. Then came the Song dynasty which was driven out in its turn by the Mongols, and who then established the Yuan empire. The last dynasty to rule there were the Qing dynasty, when the island was home to just a handful of fishermen and farmers. Then along came the imperialist British who found a good, sheltered bay for their merchants’ ships to anchor with the aim of exploiting locally-produced goods and natural resources while selling British- produced goods to the Chinese. They raised the British flag there in 1841 and the Chinese government of the time ceded Hong Kong to the British in 1842. People from further north in China fled to Hong Kong during the Taiping Rebellion and other troubles in the 1850s. Everyone has heard of what is said to be an old Chinese curse: “may you live in interesting times”. Hong Kong has had more than its share of those. It was only returned to Chinese rule officially in 1997.

The tangled history doesn’t explain how Hong Kong acquired its strange status as a country-that-isn’t-quite-a-country. It’s a story that shows Britain in a most unfavourable light, as a country so extremely determined to gain financial advantage from China and its people, regardless of how unhappy and ill it made them, that it would stoop to any depths by selling opium there. It wasn’t just that Britain was fuelling deadly addiction while finding a market for a product originating in another of its imperial holdings, India. There was far more criminal (or at least thoroughly immoral) activity than that: the “trade” was tied to blackmailing, corruption, money laundering, war, colonial exploitation and other criminal activities. Britain was not a ‘nice’ country. Imperial Britain made the Mafia look like a bunch of choirboys by comparison.

According to ‘The Saker’ website, “Part of the huge growth of British banking and of the financial power of the City of London in the 19th century resulted notably from the profits from the opium sold in China. This trade grew from around 5000 crates of opium sold in 1820, to 96,000 crates in 1873. This took place against the fierce resistance of the Chinese imperial government, which for this reason had to suffer the three so called Opium Wars waged by Great Britain against China. Expressed in tons, the British opium exports reached very nearly ten thousand tons during the year 1873. An incredible quantity for a substance sold in grams!

Immorality on that scale is hard to quantify and impossible to excuse. Britain was determined to continue making vast profits from selling addictive and dangerous drugs to Chinese citizens. The triad gangs did much of the selling and were later used by the Kuomintang to help keep the people in line, but when Mao’s Communists tackled them, they were finally defeated, along with their nasty trade. Those triad members who escaped prosecution, jail or execution fled to Taiwan or, of course, Hong Kong. Even by 1848, Hong Kong had been seen as the nerve centre of triad criminality

The British tried to clamp down on the triads, but it wasn’t easy; it was a very lucrative type of criminality. One Kuomintang general, Li Wen-huan, lived in Thailand’s so-called “Golden Triangle” in order to attack the Communists until he surrendered to the People’s Liberation Army in 1949, and he sold lots of heroin to pay his troops. He escaped to Taiwan in 1950. Drug addiction was endemic. The triads were also supplying the Americans with illicit narcotics during the Vietnam War. In order to avoid prosecution, as the authorities started to get tough on the triads, many members of the gangs moved to Hong Kong. Too many of them are still there. But what of the overall governance? Under the agreement between China and Britain in 1997, the Chief Executive and principle officers are appointed by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The Chief Secretary of Hong Kong is the most senior official, heading the Government Secretariat. It’s a complicated system.

PANDA PROPAGANDA

If you listen to Xi, of course, you’d think democracy is alive and well in China and possibly ONLY in China. Vanity, conceit and hubris would seem to be a problem for XI, although he’d never admit it, although he is, at least, trying to combat the drug-fuelled gangsterism of the Triads and their successors. However, he must believe that his thoughts are more important and cleverer than other people’s. A speech he gave to mark the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover from Britain to the People’s Republic is now compulsory reading for teachers in Hong Kong. A circular sent out to teachers by the Hong Kong Education Bureau contains the speech and urges all teachers to, as it says, “study and learn” because of “its great significance”. Copies have been distributed to all educational establishments, including kindergartens, primary, and secondary schools. How much impact it will have is somewhat open to debate. Most believers in Communism will no doubt admire Karl Marx and his two great works, “The Communist Manifesto” and the massive 4-volume “Das Kapital”. Both are extremely impressive and important works, but how much impression either of them would make on a 4-year-old seems doubtful to me.

The distribution does seem to suggest a certain level of egotism on Xi’s part, however. I rather think that the kindergarten kids in particular would probably prefer a children’s story. There are many to choose from in Chinese. There’s “Yeh-Shen”, for instance, a kind of Chinese version of Cinderella, or “Fa-Mulan”, a story about a farm girl who is obliged to become a soldier. There are lots of animal stories, too, of course, several of them including cute pandas. The participants in these tales neither read nor write political polemics for the young. Xi must really consider his thoughts to be both brilliant, and accessible.

I can’t imagine a jolly cartoon panda writing merry propaganda, but perhaps I’m wrong. And I cannot imagine Xi as a jolly cartoon panda, either. There may be more suitable comparisons and more appropriate animals. One of the books of children’s stories from China and Tibet, for instance, involves a mythical world where the animals speak but also play tricks on each other, especially enjoying a trick being played on the great striped tiger, who is portrayed as powerful, strong and scary but who can be fooled. I somehow don’t think Xi would fit the bill there?

The fact is that children, especially very young children, have a natural liking for animal stories, as well as stories of magic, fairies, demons, dragons, unicorns and other such mythical beasts. China is exceptionally rich in such tales, but as far as I can tell, Xi is not a cuddly figure who is universally loveable. Children are likely to be less interested in Xi’s innermost thoughts than in the death of the world’s oldest known giant panda, An An. He was a gift to Hong Kong from the Chinese government in 1999 and lived at an animal theme park. At 35 years, he was the oldest male giant panda in captivity and he was put down not long ago for humanitarian reasons, when he stopped eating. His age – 35 in real years – is the equivalent of 105 years for a human. His female ‘partner’ (they were never seen to mate and never produced young), Jia Jia, who was given to the safari park at the same time as An An, died in 2016 when she was even older: 38. Both animals were fond favourites for the park’s many visitors. It still has two giant pandas, Ying Ying and Le Le, but Xi has not given orders for anyone to read his speeches to them, as far as I know. It would make a change from munching on bamboo stalks, but it may not grab their attention much. It would be quite a coup, though, if both pandas simply sat down to listen, before volunteering to join the CCP.

Xi would like us to see China as a ‘workers’ Paradise’, with fair deals for all, but that is not strictly true, although education is free and senior secondary graduates have access to a wide range of vocational and tertiary courses. It seems unlikely that China’s current Politburo has much knowledge of the wider world upon which to base judgements, nor to set standards. Its twenty-five members all dress alike in dark suits and all but one are men of a similar age. There is one woman, however: Sun Chunlan, the 67-year-old head of the party’s United Front Work Department, whose job it is to spread the party’s influence at home and abroad by, for example, seeking to undermine Taiwan’s interests in other countries and trying to ensure that Chinese students studying abroad in such countries as Australia or New Zealand stick rigidly to the party line. The only other woman to have been in the Politburo, Liu Yandong, recently retired. Xi seems more obsessed with ensuring China’s pre-eminence in world affairs than with the welfare of the Chinese people. According to the East Asia Forum, only 21 per cent of all party members in China are female and only 23 per cent of all national-level civil servants are women. Further down the system, little more than 1 per cent of village committee chairs are women. All of this is surprising and disappointing, given that the party has some 92-million members and almost 5-million party ‘units’, nationwide. What is a ‘party unit’ or ‘party cell’? Well, they are the grass-roots party organisations, and are the most ubiquitous units of the party. According to the party constitution, all business, social and army units on the ground with three Communist Party members or more must set up a party cell. It doesn’t say if any of the members should be female.

The cells play an important role within the Party, with a wide range of duties, including promoting the party’s ideology, informing the public of the party’s policies, implementing decisions from higher levels and organising cadres and non-party members – or the so-called masses – to take part in social work.

At the height of the coronavirus pandemic, over 4.6-million party cells went into emergency mode and helped set up quarantine areas in neighbourhoods, taking people’s temperature and allocating daily necessities for people during a lockdown. Very good, of course, and a fine example to the world, but where are all the women? For a party that espoused gender equality long ago, it’s an unimpressive record. Uniquely for China, there is also a Standing Committee of the Politburo, made up of seven individuals elected (selected?) from among the 25. The Standing Committee meets on a weekly basis, with the full Politburo meeting once a month. There is also the National Party Congress, which is convened once five years and features 2,200 delegates elected from among the members of the party cells. They represent the 92-million party members nationwide. It’s a complicated structure in which one might think a single member might simply disappear.

THE CAT FEARS A MOUSE?

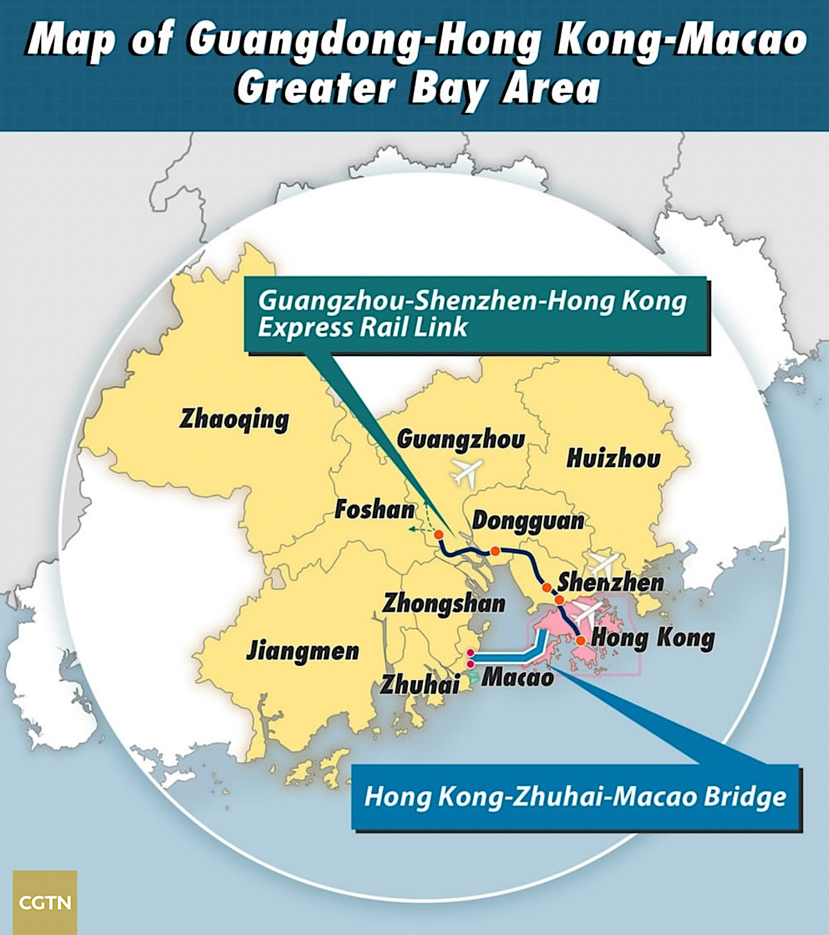

There are signs, despite the recent row over House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, that Xi is wary of Hong Kong, though the reason is hard to pin down. On a visit back in June, he chose not to spend the night in Hong Kong, preferring to slip across the border into Shenzhen, right on the border but on Chinese territory, for the night. Certainly, Hong Kong has been changed by Xi, with a ban on any kind of dissent (such as expressing mild disagreement with the government) and with compulsory “patriotic education”, which sounds like an attempt at mind control. Newspapers that are critical of Beijing find their staff being harassed or arrested. According to the rightwards-leaning New York Post, “Xi Jinping’s long-term goal is to integrate Hong Kong into the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area region.” In other words, it will become just another city in China. When Hong Kong University shut down its Public Opinion Research programme, asking what people thought about relations with China, many thought it was to save Beijing from embarrassment. Xi claimed in a speech that “Hong Kong has risen from the ashes”; The New York Post writes that it has simply been subjugated to Xi’s will. Even so, that doesn’t explain Xi’s wariness unless he expected organised violence against his person, which seems highly unlikely.

According to the New York Post, Xi is fast taking control of the city. Authorities do not permit protests and they have closed down independent media, such as the Apple Daily newspaper. Its offices have been raided several times over allegations that it had breached the hated “national security law”. Police detained the editor-in-chief and five other executives, while company-linked assets were frozen. Officials have been repeatedly harassed, apart from the raid, and police have now arrested owner Jimmy Lai, along with senior staff. The paper has been forced to close permanently. Hundreds of Hong Kong citizens have been imprisoned, many of them under the national-security law, which has been described as ‘the end of law in Hong Kong’.

China seems not to like people having the freedom to think for themselves. As a point of interest, at the time of writing, media tycoon Jimmy Lai, the owner of Apple Daily, was set to plead ‘not guilty’ to four charges, including two counts of conspiracy to commit collusion with foreign countries and one count of conspiracy to print and/or reproduce seditious publications. Six of his colleagues are similarly accused of collusion with foreign forces and conspiracy to print seditious publications. The arrests came under those strict national security laws and one of the charges could lead to a life sentence. Xi, it seems, is not only against letting people disagree with him but he also seems keen to stifle any sort of debate altogether. Politics apart, what is life in Hong Kong like? It may be ruled by a Communist regime, but is one of the world’s richest cities with more Rolls Royces per head of population than any other and also the highest number of skyscrapers in the world. For four years it has won the title of “Best Business City in the World”. And, in case you’re interested in longevity, Hong Kong people believe that eating noodles on your birthday will help you achieve that.

Xi’s approach to the West is feeding anti-Chinese feelings in western government circles, while media stories about life in Xi’s China keep the public determined to resist him. For instance, the UK has blocked the take-over by Hong Kong-based Super Orange of the small electronic-design company Pulsic, in Bristol, England, which mainly designs software to use in electronic circuits. The UK cited its reason as the risk that the technology could be used to detect and protect against electronic surveillance. The UK’s Foreign Secretary at the time, Liz Truss (now Prime Minister) urged “a tougher approach to China”, warning Beijing that it could face sanctions if it doesn’t abide by internationally acknowledged rules. It seems she included Hong Kong in her decision and “get-tough” approach. Britain hasn’t always been as quick to block Beijing’s ambitions: when Huawei wanted to get involved in the roll-out of the UK’s 5G network, it took political pressure from Washington to get the British government to take action.

China, meanwhile, makes a lot of effort to keep western countries from its own Internet services. The method has been defined by the journalist Jing Zhao, who works under the pen name Michael Anti, as “Block and Clone”, a self-explanatory phrase: China blocks one or another Internet service from Chinese access, then sets up an exact clone to which western users don’t have access. Elizabeth C. Economy, in her book “The Third Revolution” explains it like this: “China blocks Facebook, Twitter, and You Tube, and hinders Google’s search operations, which run through Hong Kong, while supporting homegrown Internet companies such as Baidu, Tencent, Benren (a Facebook copy), Youku and Tudou (Youtube twins owned by one parent company) and Sina.” All of these are copies of Western Internet services. If that sounds scary, read on.

Elizabeth C. Economy again: “The government’s ability to ensure that its political restrictions – controlling content that comes in, is transmitted, and goes out – are followed is far greater with Chinese companies than multinationals.” It seems that Xi takes a very personal hand in it all. To quote Economy again: “In addition, Xi Jinping has increased the challenge for foreign media and Internet companies to gain access to the Chinese public.” Those challenging Beijing’s control can find themselves in trouble, like 47 prominent legislators and activists who have been charged under the National Security Law for engaging in peaceful, non-violent political activities. Five of them have now been named as ‘major organisers’ which could suggest they face very harsh sentences for not agreeing with Xi.

It makes it look as if Xi and his acolytes are afraid that if the people of China get even the merest glimpse of what life in the West is really like they’ll choose to overthrow Xi and launch a more liberal and tolerant China, however impossible that may seem. All they want is democracy, which Xi says they already have. Xi has claimed that democracy is only awake at election time in the West, while in China it’s a permanent feature. He says that westerners have no voice once the voting is over with. And strangely, he sees himself as the only solution. “Democracy is not for decoration,” he said, as if we didn’t know, “but for solving problems that people need to solve.” That’s not its normal definition, of course; according to my Chambers dictionary, it means “a form of government in which the supreme power is vested in the people collectively and is administered by them or by officers appointed by them”. In other words, ‘the people’ are supposed to be in charge. But how, one might ask, does ‘the people’ speak; how are they represented when they have a point to raise? Xi replied: “this happens through the leadership of the Party.” But can the people ever believe that Xi is listening to them, let alone taking any notice, because he never shows any sign of it? “Evidence that the Party represents the people is offered by the ‘economic miracles’, and the building of a powerful and stable nation.” That almost certainly doesn’t mean he’d appreciate a letter pointing out how and where something is going wrong, unless the writer fancies a brief holiday behind bars, or worse. As the CNN News website pointed out, the same criteria could have been applied before the Second World War to prove that Nazi Germany was a powerful, prosperous, and stable country where human rights flourished. Once again, it comes down to a definition of what the word ‘democracy’ means, just as Humpty Dumpty said. In China, it means whatever Xi wants it to mean.

We live in a world where appearances are very important, in some ways more important than simple facts. For instance, in America an administration must talk tough about China whatever policies it’s following. Kishore Mahbubani, a former diplomat and an academic, in his book, “Has China Won?”, writes that: “On purely ideological grounds, any American administration must appear sympathetic to demonstrators in Hong Kong clamouring for more rights. American public opinion demands that the United States support the demonstrations. However, any shrewd American administration should also balance public opinion with a sound understanding of the core interests of Chinese leaders.” It’s also worth bearing in mind the imbalance in terms of the size of the population. The United States has a population of 330-million people. China’s population is 4.242 times as great, and that’s a lot. Of course, in the event of a war, the sheer size of a population is not a good guide to predicting the outcome. Winning or losing depends on training, tactics, the skills of the officers planning the battles, the determination of the combatants, how good their weapons are and how well the soldiers can use them, among many, many other things.

Mahbubani points out that, whatever its image, China has shown restraint in dealing with all the protests in Hong Kong. Many of the protests were against the proposed legislation of Hong Kong’s then chief executive Carrie Lam, who tried to get an extradition agreement with Taiwan and China. Opposition was so strong that she withdrew it. Both the United States and India have, at various times and in response to a variety of provocations, ignored international advice – and international law – to invade and take over countries with whose policies they disagreed. China hasn’t done that, to its credit. Hong Kong has certainly given it provocation. Hong Kong Demonstration leader Joshua Wong told Agence France-Presse that he is not a separatist, he just wants the people of Hong Kong to be able to elect their own chief executive, a concession which Beijing actually agreed to before 1997. Despite that promise, the Chief Executive is selected by an Election Committee dominated by pro-Beijing politicians and (this is the strange part in a Communist regime) by tycoons. But as is the case with most demonstrations, the bottom line is poverty. Hong Kong’s property tycoons have persuaded the government not to allow more building as a way of boosting the value of their investments in real estate.

As Mahbubani explains, things are very different (and much better) in Singapore. In Singapore, US$1-million would buy four apartments of around 932 metres each. In Hong Kong, the same sum would buy just one, with only 232 metres of living space. According to Mahbubani, the demonstrations in Hong Kong are not so much against a tyrannical regime in Beijing, they’re really against rapacious and greedy property barons who have managed to boost the value of their assets by lying and trickery. The real estate tycoons are the real enemies of the people. In Hong Kong, unlike mainland China, Mahbubani says that the bottom 50% of Hong Kong’s population have seen their living standards worsen so much that finding accommodation of any sort is difficult. There is a lot of homelessness. The question is whether or not Beijing has the inclination to stand up to the gluttonous business tycoons who don’t want their wealth diluted by developers building enough homes to bring the prices down.

It has happened in Singapore; why not in Hong Kong? Mahbubani says it nearly happened when Hong Kong’s first Chief Executive, C.H. Tung proposed ways of increasing home ownership (and reducing homelessness) in a bid to emulate Singapore. Hong Kong’s wealthy real estate barons persuaded Beijing to overrule Tung. His plan was shelved, and homelessness mushroomed while the property barons became immorally and quite unscrupulously rich.

Beijing is against uprisings of any sort, as is the current Chief Executive, John Lee Ka-chiu: the rule of law must always win, even in fiction. The latest “Minions” film, in the “Despicable Me” series, for instance, would have showed arch-villain Gru escaping from justice again, (as it does in the version being shown in the West) but China has re-edited the ending and added a text that explains how Gru’s mentor, Wild Knuckles, was sent to prison but reformed himself while inside, so that a Chinese audience will see wickedness defeated and good triumph. I’m not really convinced that a cartoon kung-fu comedy can influence people’s views or stop children from choosing a life of crime, but Beijing clearly thinks it can. Does this mean that a film of, say, Lord of the Rings would end with the Hobbits persuading the evil Sauron to mend his ways, marry and raise a family, while Gollum would join the Boy Scouts? It would lose some of the dramatic tension of J.R.R. Tolkien’s original, I fear. Where are Aragorn, Elrond, Galadriel and Gandalf when you need them? Only if you need them, of course.