F-35B Lightning IIs fly over Wake Island, August, a U.S. Territory which is a strategic refuelling stop for military aircraft in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. © Francisco J. Diaz Jr.

Think of an island in the Pacific and you’re likely to imagine palm fringed sands, coconuts falling from trees and hula dancers. A few years ago, during a working visit to the beautiful country of Togo in Africa, a friend of mine was knocked unconscious right before my eyes when a coconut fell on his head. The coco palms there were very tall, so it had fallen a long way before connecting with his head with a loud, hollow “clonk” sound. It wasn’t funny but we laughed, even so (and he recovered quickly once he regained consciousness). If, however, you are a strategist in Beijing you may imagine man-made islands instead, dotted with early warning stations and sites from which to launch missiles or fire heavy weapons in the event of conflict. There are also helipads, anti-ship missile batteries and in one photograph two Type 022 Houbei-class catamarans which are fast-attack missile carrying vessels, according to an analysis by The War Zone publication. To be perfectly frank, the entire sea was misnamed. “Pacific”, after all, means peaceful, but with frequent storms, strong winds and sometimes mountainous waves, it’s seldom as peaceful as its name suggests, even without the world’s politicians and armed forces getting involved. Perhaps that’s just as well because it seems as if China’s view of the Pacific Ocean is somewhat different anyway. Xi Jinping seems to think the Pacific has too few islands, so he has decided to create a few more.

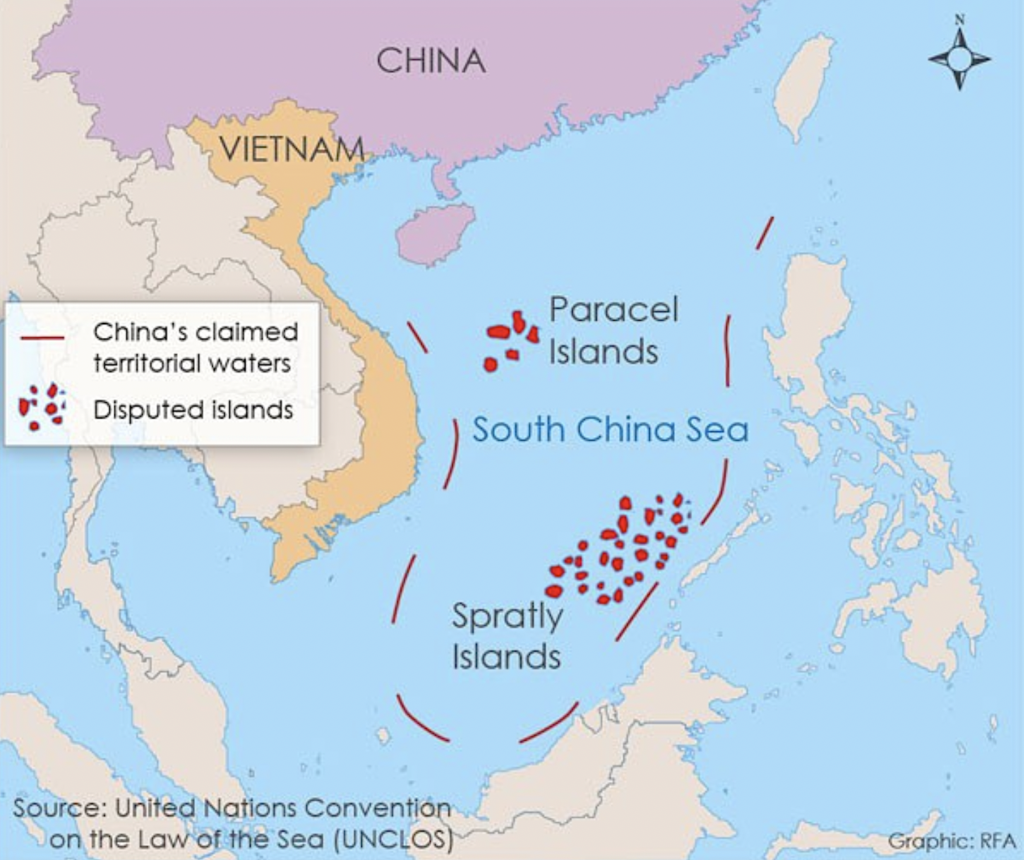

Take a look at the Spratly Islands, for instance, in the South China Sea. They form a disputed archipelago of not only islands but also islets, cays, and reefs (lots of them), there are also some old atolls that are partly or wholly submerged. The archipelago itself lies just off the coasts of South Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia but recent aerial photographs have revealed that its component parts now serve China as a major intelligence source and military base, complete with missile-launching boats, runways (one of them three kilometres long) as well as a KJ-500 early warning and control aircraft.

The United States is nervous about the development, of course, especially as the Spratly chain seems to be growing, with new, previously uncharted islands popping up where there were none before.

“No man is an island” is the title of a poem written by John Donne in 1623. Arguably, it’s not a poem at all, but a prose section of a larger work, written while he was ill. It is meant to suggest that we all need each other and cannot exist as single, unrelated entities. Certainly, when a vessel gets into difficulties in the unforgiving ocean, he or she may need the help of others, but that probably isn’t the thinking of Xi Jinping. He seems to be concentrating more on facilitating attacks on potential enemies. As it is, the facilities China has installed could be used to cut off shipping routes that currently supply Taiwan and Japan, preventing access from the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Washington claims to be monitoring developments in the region very closely.

China’s interest in French Polynesia began in the 1980s. In the years that followed, China acquired a number of hotels, among other investments, all seemingly aimed at increasing its influence. In recent years, it has acquired several hotels including two with five-star ratings and also has an important diplomatic network within the archipelago. It has now extended its influence beyond the purchase of real estate and has got involved with investment projects, such as creating an aquaculture area on the Hao archipelago, the furthest archipelago from Tahiti, located 919 kilometres from the local capital. Xi is nothing if not ambitious and he’s clearly interested in more than hula dancers.

To carry out this massive project, China would invest more than 600 million euros over the next ten years. There are clearly going to be huge economic benefits for the archipelago, according to L’École de guerre économique (the School of Economic Warfare, or EGE). However, hidden behind this project is an overwhelming ambition on the part of Beijing, whose primary objective is to meet ever-growing domestic demand for fish. The waters of the Exclusive Economic Zone of French Polynesia are rich in fishery and mineral resources. But Beijing’s real goal is to expand its sphere of influence to the far reaches of the Pacific. Of course.

| WANTING IT ALL

So, what has this got to do with what’s happening among the Spratly Islands? According to the EGE, “To achieve its goals, China has built an important network of influence within the archipelago,” which is clearly what US spy planes have been photographing. “The aquaculture project shows the desire to exclude France in its Indo-Pacific policy and this on its own territory. Thus, it was able to take advantage of the 1982 Defferre Accords allowing French Polynesia to acquire autonomy in its administrative and financial management, only the sovereign poles such as Defence and Justice are retained by the Metropolis.” None of this makes easy or comfortable reading in Washington, but in view of the region’s proximity to Australia and New Zealand, it doesn’t go down too well in Canberra or Wellington, either.

In 2007, China created a consulate on the island of Tahiti. Although it had a purely administrative role, the Consulate serves (and successfully) to help Beijing increase its influence on the island. This makes it possible to extend China’s influence in the economic field by improving connections with the local business network. By using this facility during the Covid-19 crisis, Beijing was able to use what’s been called “its diplomacy of the mask by delivering 2.2 million surgical masks and 15.8 thousand FFP-2 masks”. FFP-2 masks are the kind you can buy in a pharmacy.

This policy has increased China’s hold on the island by “replacing the French State in its sovereign role of protecting the population”, as EGE expressed it. Finally, in 2013, the Confucius Institute was formalized within the University of Papeete. You might almost argue that China was using the beliefs expressed in John Donne’s poem about no man being an island to make itself invaluable and completely essential. And it doesn’t end there, with China and the United States competing with each other for influence. According to Reuters, delegations from both countries have been visiting Honiara, the capital and largest city of the Solomon Islands, situated on the north-western coast of Guadalcanal, both hoping to extend their countries’ influence.

The China International Development Co-operation Agency has been funding infrastructure projects in the Solomon Islands ever since 2019, when Solomon Islands Prime Minister, Manasseh Sogavare, changed his country’s diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to Beijing. But to be on the safe side, Sogavare met with not only the vice chair of the China International Development Cooperation Agency, Tang Wenghong, but also with Kurt Campbell, Indo-Pacific coordinator of the US National Security Council, with whom he is said to have “reiterated our support for a free, open, secure and prosperous Solomon Islands”, according to a statement from the US Embassy in Honiara.

But while Australia, New Zealand and Japan worry about Chinese intentions, “closely monitoring developments which might impact on our national interests,” China none-the-less plans to upgrade the ageing international port in Honiara and two domestic wharves in the provinces, with the multi-million dollar construction contract going to the sole bidder in “a competitive tender”, the China Civil Engineering Construction Company, according to Mike Qaqara, who is an official at the Solomons’ infrastructure development ministry. The prospect of a “new military base” so close to Australia has raised a few eyebrows but according to the Eurasian Times, this has been dismissed by Beijing as “baseless hype”. One imagines that China would show rather more concern if Australia, New Zealand or Japan started building something similar on China’s doorstep. Meanwhile, the Solomon Islands’ government has welcomed the $170-million (€1.56-million) project, funded by the Asian Development Bank, which includes improvements to the old port, construction of a new domestic port and the roads needed to service it all. Both the Solomon Islands and China have denied that the upgrade will include a naval base, pointing out that their security pact would simply not permit it. Doubts have been expressed, however, by the Prime Minister of Samoa, Fiame Naomi Mata’afa, one of the ten Pacific island leaders who declined to sign a regional trade and security pact with China. She told the media in Australia: “This is a commercial port, although it might morph into something else…’dual purpose’.” That would not go down well in Canberra.

| TOO FEW ISLANDS? LET’S BUILD MORE

It’s now being reported by Western officials that China has been enlarging and building on land in the Spratly Islands group for the first time. Previously, China had militarised reefs and island land formations, apparently as part of its bid to seize control of vital commercial shipping routes, something Western leaders fear. Now, according to Bloomberg, the New York-based news agency, it has begun to build military infrastructure on land not previously owned or controlled by China. The work has been carried out by Chinese maritime militias at four sites it did not previously occupy. It has also been building up industrial infrastructure on islands it has constructed in the disputed waters. Needless to say, the United States is not the only Western power to dispute China’s claim to sovereignty over the South China Sea. It would be a very valuable resource for China if it was permitted to exercise that assumed power: eleven billion barrels of oil, as yet untapped, and, according to the Center for Preventative Action, 90-trillion cubic feet (5.4-trillion cubic meters) of natural gas. China has not only annoyed the United States with its territorial claims: Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam are also concerned. What’s more, in addition to the oil and gas, the Spratly Islands provide rich fishing grounds.

China claims that the area is part of its “Exclusive Economic Zone”, its EEZ, and that under international law that means that foreign militaries cannot undertake intelligence-gathering activities there, which would ban reconnaissance flights.

China likes to warn off potential rivals by threatening them with laws that it prefers to ignore. In these days of satellite imagery, it would seem to be a fairly pointless ban. In 2016, the Philippines brought a case against China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague under the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea. China lost on most of the country brought but it declines to accept the court’s authority. Given that it ignores international law, it has built ports, airstrips and military facilities all over the Paracel and Spratly islands, as well as militarising Woody Island with cruise missiles, fighter jets and a radar system. The United States has tried to counter China’s over-reaching ambition by seeking to uphold the Un Convention of the Law of the Sea, conducting Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) and talking up its support for partner nations in Southeast Asia. China only appears to believe that its own laws should be followed. But the United States is determined to maintain freedom of navigation in seas that only China believes it owns. And, of course, Beijing continues to construct bases with a strong potential military use. Not to be out-done, the United States has increased its own military activity in the region, including more FONOPs, during 2018.

In 2013, the Confucius Institute was formalised as part of the University of Papeete, ostensibly with the aim of promoting Chinese culture internationally with such events as exhibitions to show off the social and technological advances made by the Chinese Communist Party. Some have accused it of seeking to influence the faculty and even being behind possible acts of corruption, although there is no proof. Paris has been receiving warnings about the dangers of Chinese activity since 2014, but it has only now started to react. According to EGE, it was not until President Macron travelled to Polynesia in July 2021 that there was a real response from France to the Chinese involvement in the island and the stupidity of it in ecological terms. The State is supported by ecological associations who publicly (and loudly) condemn the nonsense of the aquaculture project. As the EGE points out, future fish will be raised in waters that are still potentially radioactive. Anybody want a radioactive salmon? From 1966 to 1996, the Hao archipelago was home to the Pacific Experimentation Center, the organization used to conduct nuclear tests in the region. Such a concentration of fish at that time would inevitably lead to the pollution of the waters that will flow out of the lagoon and pollute the fishing areas of the archipelago. China seems somewhat oblivious to environmental issues where its economic and military interests are concerned.

According to EGE: “If China can afford to project its ambitions on the most insular territory of French Polynesia, it is partly due to its management of the project’s communication. Patiently but surely, it has been able to infiltrate the different strata of the economic and political circles of the archipelago. With the support of its diplomatic institutions based on the island, it disseminates its thinking and extols the economic and political benefits of increased relations between the two parties.” It was Teddy Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States, who, speaking in 1901, first used the expression: “speak softly, and carry a big stick.” It’s a saying that Beijing seems to have taken very much to heart.

From a social perspective, the French State has undertaken restoration work on Hao Atoll in order to build an Adapted Military Service Regiment (RSMA) that allows young people aged 18-25 who have dropped out of school to build a professional project in a military setting. And if China is sometimes slow to respond, it’s not alone, according to a report by the EGE: “Aware of the delay, the President of the Republic has tried to show his support for his overseas department through various visits to the archipelago on the theme of preserving the environment, the local economy with particular attention to local fishermen and the investments to be made to develop social action.”

China’s pursuit of the offshore resources it has boasted about has not been welcomed in the United States, where Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has described it as “completely unlawful”. He accused China of employing bullying tactics to gain control over the disputed waters. For its part, China says the US distorts facts and international law, although it goes on building military bases on artificial islands, always against Washington’s wishes, although it has not accused them of being “illegal” until now. Relations between China and several other countries have been worsening recently, although it’s unclear what the USA might want to do about it.

As I mentioned earlier in this article, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam contest China’s claim to almost all of the South China Sea. The countries have wrangled over territory for decades, but tension has steadily increased recently. Beijing claims an area known as the “nine-dash line” and has backed its claim with island-building and patrols, expanding its military presence there, although it insists its intentions are peaceful. It’s hard to be convincing about your country’s “peaceful intentions” when they’re backed up with military threats. In denouncing China’s territorial claims, Pompeo said that China has “no legal grounds to unilaterally impose its will on the region.” He told the media that Washington rejects Beijing’s claims to the waters off Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia, stressing that any action by the People’s Republic of China action “to harass other states’ fishing or hydrocarbon development in these waters – or to carry out such activities unilaterally – is unlawful,” adding that: “The world will not allow Beijing to treat the South China Sea as its maritime empire.” But that may, of course, be wishful thinking.

No-one is about to back down, of course, which leaves the situation in limbo. In the meantime, it seems to be a somewhat one-sided dispute, with China arguing that it is not bound by international conventions or laws while at the same time using them to condemn the actions of others. At the end of the day, of course, it all comes down to money and power, which China wants to secure for itself in the face of opposition from neighbours. When a BBC team flew over the disputed area aboard a US military aeroplane, the pilot was warned to leave immediately “to avoid confusion”. But there is very little confusion, just a lot of threats and posturing by a country determined to impose its will. There is surely no obvious misinterpretation of its intentions: building airports, negotiating local deals and China’s claim of territory leave little room for confusion. For example, France constructed an 8-kilometre runway on Hao Atoll (also known as Harp Island) that was designated as an emergency landing site for NASA’s Space Shuttle. It’s of particular interest to China as a former French military base, formerly used for France’s nuclear tests.

China is developing Hao Atoll (or rather it is being developed for China by Tahiti Nui Ocean Foods) for aquaculture with the backing of the archipelago’s Vice-President, Tearii Alpha, despite criticism of the deal from France’s President Macron. Located in the Tuamotu Archipelago, Hao also has a 3,420-metre military airstrip, which is one of the longest in the Pacific. With a population of around 1,700, Hao served as a staging post between France, Papeete and the nuclear testing sites at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls, where France conducted a total of 193 nuclear tests between 1966 and 1996.

We will have additional information for you in the next edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine but focused more on the issue of China’s global fishing expansion. Who knows what may have happened there by then? While all parties seem keen to play down their military interest in a place, you can be sure that ambitions are being honed and will be very far from what ever the politicians may be saying! Perhaps we should recall the last lines of John Donne’s poem about ‘no man being an island’, too: “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

anthony.james@europe-diplomatic.eu