Training diplomats for a fractured world

Diplomacy, according to my Chambers Dictionary, is “the art of negotiation, especially in relations between states”. However, my rather more elderly Walker’s Dictionary from 1850, has a very different definition: “the state of acting by a diploma”. That’s rather appropriate: how does someone get a diploma in diplomacy? It takes training to learn the skills a diplomat will need in today’s uncertain world. Diplomacy – and those with the necessary skills to do it – have never been more needed. “The qualities of a diplomat are multiple,” Fouad Nohra told me. He is an Associate Professor in political science at a Paris university as well as being Academic Director of the Centre d’Études Diplomatiques et Stratégiques (CEDS), an educational institution that trains diplomats, among other things. We were meeting at the CEDS training facility in the 7th arrondisement, not far from the tourist-haunted and better-known Eiffel Tower. “The first thing is knowledge, because you cannot be a good diplomat if you do not know the political situation. If you are just a hostage to your stereotypes you would have to get out [of the profession].”

In other words, you cannot approach diplomacy from behind a pile of preconceived ideas and prejudices. “You have to develop your political thinking,” Nohra told me. “The second quality is pragmatism: being able to move according to the constraints of reality and not being led by your conceptual perception or your theoretical knowledge, acknowledging that the theory will never be able to match the practice.” In other words, don’t assume you know the situation on the ground as well as the people whose day-to-day experience it is.

CEDS was created thirty-two years ago by Pascal Chaigneau, a University professor and Director of the HEC centre for Geopolitics, (part of the École des hautes études commerciales) as well as being Dean and Founder of CEDS. It was originally established as a place where diplomats working in Paris could meet and develop their knowledge. Over time, its specialised programmes were expanded beyond the diplomatic world to train international civil servants and military attachés from more than a hundred countries. Since 2017, CEDS has been in partnership with UNESCO to help promote peace studies. Given the current state of the world, peace studies have seldom had more relevance. Now the new board is headed by Philippe Cattelat, a renowned director at the L’Institut des hautes Etudes Economiques et Commerciales (INSEEC U) group, which owns CEDS, and Fouad Nohra is working with Florence Gabay, a Chief of Staff at the French National Assembly, who was recently appointed as a Development Director for the Centre.

Just forgetting to abide by local feelings can make all the difference; cultural sensitivity is vital and forgetting that can be very dangerous. Local conventions are important: never suggest your interlocutors are beneath you or in any way inferior. It may seem like an obvious thing to follow the protocols of those with whom you’re negotiating and not to hurt their feelings, but politicians and others can get it badly wrong. It’s what Nohra says is the ‘third quality’ a diplomat needs: “the ability to understand other cultures and other peoples.” Nohra cited one especially good example of a French ambassador, Michel Raimbaud, who taught for more than a decade at CEDS, and who was sent to various African countries. “He was appointed wherever there were crises,” Nohra said, “in Zimbabwe, in Sudan, in Mauretania. He was in Egypt and other countries in the Arab world. He learned Arabic and he knows how to understand the culture of the Arabs and how to speak with them.”

TALKING IS GOOD FOR YOU – USUALLY

That’s a lesson that not everyone in the diplomatic service seems to have learned. “The problem of some diplomats who are trained by their governments is that some governments tell them ‘always keep your distance’”. Nohra is convinced that is bad advice. “To keep a ‘poker face’ is what is taught in many academies, but I do not believe in it. I don’t believe in the ‘poker face’ attitude in diplomacy. I believe that the ability to engage in dialogue, the ability to face others, is one of the key qualities in a diplomat.”

for the Centre and Chief of Staff at

the French National Assembly.

Photo French National Assembly

Today, of course, fears over the spread of the corona virus are making that very difficult. Some reports claim that it has all but halted international diplomatic efforts, with major summits cancelled and diplomats left stranded by temporary travel bans. Even the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has now cancelled or postponed a number of conferences on subjects ranging from human rights to the Law of the Sea and, somewhat ironically, antimicrobial resistance. Nohra is worried that international reaction to the virus will lead increasingly to people only communicating electronically, rather than face-to-face, and that this will play into the hands of populists governments deliberately fomenting an ‘us-and-them’ attitude that could drive a wedge between their people and those of different nationalities, thus creating a pool of people to blame when things go wrong.

There have been cases where leaders would have been better to leave the job of negotiating to professional diplomats.

For instance, Harold Nicholson was a junior diplomat for the United Kingdom at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 where he was upset that the leaders and heads of government there were getting it wrong. “Amateurish diplomacy leads to improvisation,” he commented afterwards. “Nothing could be more fatal than the habit (the at present persistent and pernicious habit) of personal contact between the Statesmen of the World,” he wrote. “Diplomacy is the art of negotiating documents in a ratifiable and therefore dependable form. It is by no means the art of conversation.” Now, in the age of hastily-written emails and unwise late-night Tweets, this is more than ever the case, according to the Politico website. “Traditional diplomacy is becoming archaic,” the site quotes a veteran US State Department official as saying, whilst admitting that not everybody in Washington, London or Brussels might believe that that’s a bad thing. “It’s like the coal industry — should we really rescue it?” he asked. If the alternative is further misunderstanding, possibly leading to war, surely the answer must be yes?

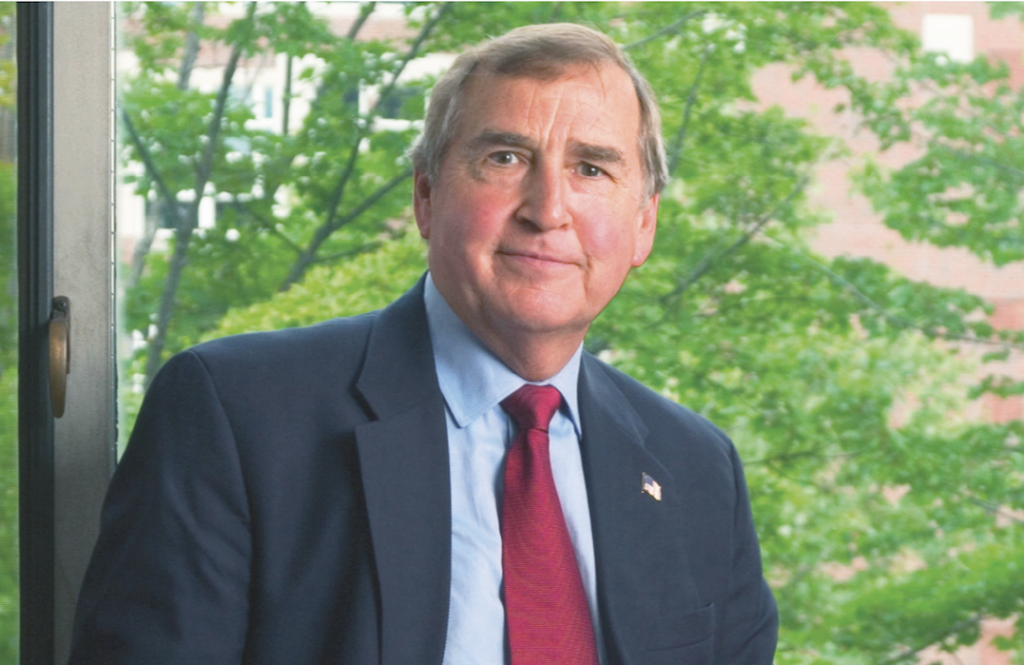

However, there are claims that President Donald Trump is increasingly seeking to side-line professional diplomats in favour of political appointees who are more likely to follow his instructions, however undiplomatic they may be. Political appointments now make up around 45% of the US diplomatic service, according to the American Foreign Service Association, a kind of trade union for US diplomats. Many of today’s appointees are from business backgrounds.

to the EU © Wikipedia

Gordon Sondland, who had worked in the hotel industry, was Trump’s choice for Ambassador to the EU, where he was reported to have said that his mission was “to destroy the European Union”, hardly a diplomatic remark calculated to endear him to his interlocutors in Brussels, Berlin or Paris. Then there’s former journalist Richard Grenell, Trump’s ambassador to Germany, who enjoys annoying his hosts in a way some argue reflects more faithfully Trump’s approach to foreign policy. Grenell says he wants to “empower” conservatives in Europe, and in so doing is not playing to please the public but purely to entertain and delight his boss. “Trump wants that kind of message,” said a State Department official, quoted in Politico. “If it smashes the china, that’s OK. He’s being a disruptor.” Grenell is certainly not popular in Europe and his effectiveness is open to question. “Current American diplomacy is less effective in defending US interests than the current administration appears to believe,” one senior German diplomat told Politico. However, there is a rôle for business people in diplomatic relations, says Nohra. “When you do business with somebody you hate, finally you stop hating him because you make money with him.” We shouldn’t forget that when Robert Schuman made his famous speech on 9 May, 1950, effectively launching the European Coal and Steel Community that would evolve eventually into the European Union, he said that by uniting the industries that were “the engines of war” – coal and steel – it would prevent the participating parties from fighting each other.

And it has. Similarly, Nohra pointed out that up to now, there has seemed very little chance of a shooting war between the United States and China, and this despite the last warning of Graham Allison, the American political scientist and long-serving Professor of Government at Harvard University, who predicted that one dominant power could be nudged into war by another that is growing in power and influence. He called it the ‘Thucydides Trap’. “China was, until very recently, the first creditor to the US Treasury, the first exporter to the USA. The US relies on Chinese imports and the US exports a lot to China.” Financial interdependency can be an aid to long-term peace, however much sabre-rattling goes on between Washington and Beijing.

If, on the other hand, diplomacy is to smooth over misunderstandings and help avoid conflict, diplomats need to be trained professionally, not by their governments, and they must understand the people with whom they’re dealing. CEDS runs a number of programmes, not all of them designed to produce professional diplomats. Among its specialised objectives in Paris, claims its brochure, its primary aim is to meet the needs for upgrading and updating the knowledge of senior civil servants, diplomats and decision-makers in the fields of international relations, defence and security strategy, and the communication of influence developed by the new media. Graduate studies are primarily intended for diplomats, civil servants, senior executives and senior officers holding a Master’s degree. Since its creation, senior officials from over 100 countries have been trained there and are now working around the world as ambassadors, plenipotentiary ministers, military attachés and in a variety of other rôles. These courses are run in French but CEDS also has a PhD course in international relations and diplomacy which is taught in English and designed for diplomats, senior civil and military officers, and the senior executives of private companies. CEDS has branches in seven cities altogether: Athens, Rome, Rabat, Ankara, Antananarivo, Dakar La Paz, Tokyo and Seoul, and they operate independently, although for their academic courses their curricula are controlled from Paris.

DON’T BLAME ME, BLAME THEM

These days, people fulfilling diplomatic rôles, whether or not they are working as professional diplomats, have to be wary of political leaders who try to excuse their own failings by whipping up a storm of nationalist feelings against other groups, whether that is immigrants, asylum seekers, neighbouring countries or people with different or no religious faiths. “Demagogic leaders and people who make extremist speeches never deliver what the people really need, they deliver what they push the people into believing they want,” argues Nohra. He cited an example. “When you have a phenomenon like unemployment in a country where there is immigration, you can believe that unemployment is due to the economic system, then you want to change it. You can believe that unemployment is the result of immigration. Then you push the immigrants out. You can believe that unemployment is coming from the fact that people are lazy and won’t work, then you cut off their social benefits and push the people onto the jobs market. These are what people can believe but none of these answers is true. The reality is much more complicated.” Nohra says that populist governments prefer to propose simplistic solutions because doing so excuses and wins support for extreme measures. “The problem for these politicians is to persuade the people to believe in one of these extreme theses in order to organise the people in a way that suits their political agenda.” Look around the world and it’s not hard to see examples, in Europe and further afield, where hate-speech is helping to keep demagogues in power. If you can’t deliver what they need, goes the argument, give them what you want instead – and work to ensure they want what you want. It’s easier, cheaper and helps keep you in office for longer.

Now the world is facing up to the corona virus issue, which Nohra says is considered a ‘safe’ subject to raise at a diplomatic level: everyone is against the virus so opposing it cannot be controversial. “The corona crisis means that all of humanity is against the virus,” he told me, “so this is consensual speech, to talk about corona now, about fighting against corona.” He added that “health diplomacy has for a long time been treated as a matter of ‘low politics’ for many governments which used to put the greatest emphasis on military issues as well as on resource control”. That is not in any way to downplay the seriousness of the pandemic and the fear it is causing. Even so, there were rumours being circulated on Indian social media sites suggesting that corona had been created in Chinese military laboratories as a weapon, just as there were rumours when AIDS was first diagnosed that the HIV virus had been created by American scientists to use as a weapon in Africa. US officials claimed Beijing had been too slow to take action when covid 19 – the illness caused by the corona virus – was first detected in Wuhan late last year.

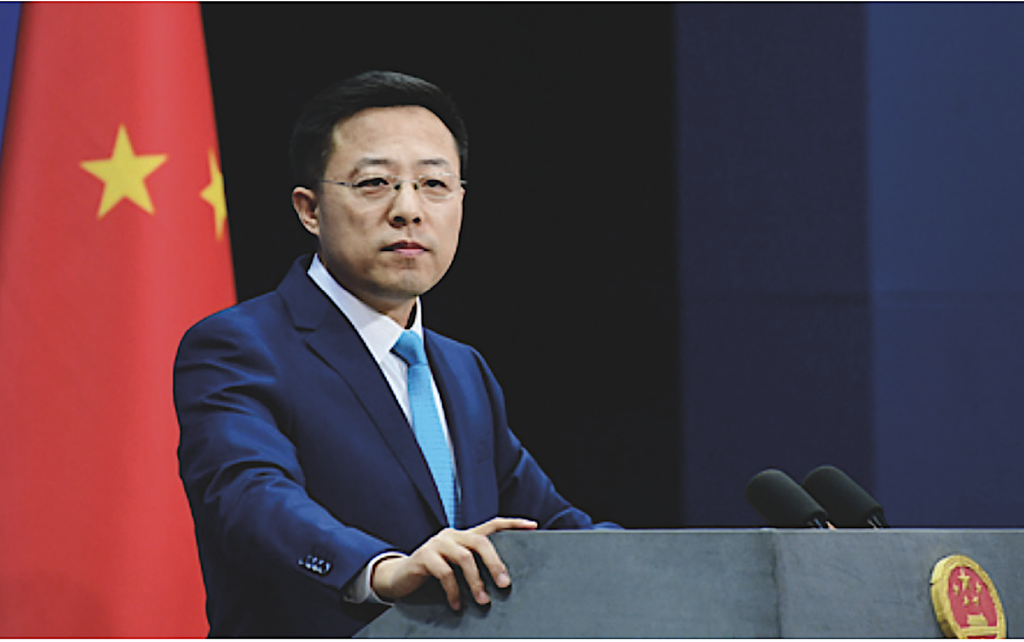

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian © fmprc.gov.cn

Now Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian has tweeted that the virus could have been brought to Wuhan by the US military. He offered no proof. Such ideas would be risibly ridiculous but, as the old saying goes, mud sticks and some people are going to choose to believe it or something like it. It’s comforting to have someone to blame, especially if they’re foreign. “The perception of the world is one thing, the reality is something else,” warns Nohra. He points out an article he wrote “on the transformation of the media world and the fabrication of the enemy” (Entertainment and Law, April 2019, p223-238) in which he mentioned the way in which extremist social networks and media gave a misleading interpretation of photographs of refugees and asylum seekers crossing the border into Europe. They cleverly selected only those photographs that showed lines of young adult men, avoiding those pictures (the majority) that included women and children. The groups misusing them in that way wrote “These are not refugees, they are terrorist invaders”. Extremists are always willing to use misleading images to support a lie, knowing that their followers will believe it without question. Hate is a great driver of populism.

THIS COULD CHANGE EVERYTHING

The corona virus issue, though, poses another problem, which worries Nohra. “I think this will bring about a change in civilisation and in social habits,” he says. We’re not just talking here about the deaths of individuals but the possible death of society and the body politic, he fears. “This will consolidate the distance between people, this will consolidate the distrust and the fear, and this will maybe produce two things. Firstly – and I am afraid of this – is de-globalisation, which means that each country will disconnect [from others].” Diplomacy, after all, is built on contact, and it’s starting to go wrong. “Now the United States has banned travel from Europe for one month and if it continues, it can be for 2,3 or 6 months,” he says. In the days since we spoke, entry restrictions have also been put in place by the European Union, Russia and a number of other countries, too. Nohra is concerned at the way in which so many people already spend so much of their time staring at the screens of their smart phones instead of talking. We’ve all seen young couples (and not such young couples) sharing a table in a restaurant or bar but staring at their ‘phones, rather than engaging in conversation. Nohra fears that the virus will make this worse. “It can move socialisations from real to virtual. Virtual, because everything will be done through your screen. This is important. This is very, very interesting to see, because it is already the case for many but it will increase the issue of people staying behind their own screens for everything they need and with few people moving to deliver things they want.” The world would become largely immobile and people who don’t meet face-to-face seldom fully understand one another. Some observers have noted that this sort of isolation, with places of public entertainment, non-food shops and restaurants closed, quarantining the elderly and all travel restricted plays into the hands of populists. If people are unable to discuss their concerns with others, the fear will worsen. Many of the isolated elderly will die, especially if they live alone and are not allowed access to shops and other public facilities. And it could kill society as we know it for a generation.

to the USA © Wikicommons

Diplomacy can be a hazardous profession. Take the case of Sir Kim Darroch, who was the British ambassador to Washington from January 2016 to December 2019. He made critical remarks about President Trump in a private communication with the British Prime Minister but they were leaked to a newspaper and he was forced to resign. In this age of Wikileaks, Tweets and other means of instant (often poorly thought out) communication, there is no such thing as complete security for the transmission of reports and documents. It’s been reported that some diplomatic staff, fearing hacks to their official laptops, have taken to using public facilities at airports to send private messages and emails instead. There’s less chance that the message will be hacked. America’s Democrats, especially one-time presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton, know how dangerous that can be, although she also knows that it’s not wise to use one’s private email account, either.

However, despite this move towards a ‘silo’ society, Fouad Nohra says the fight against corruption in government is helping to overcome ethnic rivalries, because it’s a universal effort. The fight against corruption is bringing people together, whatever their religions, their ethnic groups, their opinions, in order to reform a country that is ill.” This shared perception of the need to correct a corrupt and inefficient government can overcome decades of mutual hatred and mistrust. “Take the case of Iraq,” Nohra suggests. “People are going against their own religious leaders because they want to hold them to account. You have demonstrations by people who have gathered from all different sects. They are saying ‘I want to have a different life, I want to look after my home, my job’, I want to live differently and I don’t want the people above me to spoil things and take my money’.” Finding that there are points upon which people of different backgrounds can agree is a good starting point.

OPEN YOUR MIND

The University of Southern California and the Center for Public Diplomacy (CPD) run an interesting programme called 22.33 that emphasises the need for people – diplomats especially but not exclusively – to get to know each other better. Knowledge of ‘the other’ fosters better understanding. As it says on its website: “If there is a recurring theme throughout 22.33, it is the undeniable human need for belonging. Despite all the differences, challenges and culture shock one experiences while traveling abroad, each story moves beyond feeling foreign, language barriers or weird food, to focus on radical hospitality, deep curiosity and breaking down stereotypes.” I couldn’t agree more, and it sounds like a very interesting initiative. The 22.33 programme is based around podcasts so that people from all around the world can share their experiences and overcome their reluctance to mix and mingle. “Everybody has a story. Whatever the subject – and one never knows what the next podcast episode will be about or where it will originate from; it could be from anywhere, about anything – the foundation that 22.33 builds upon is humanity.”

Communication is vital and it’s one of the skills in which CEDS trains not only potential diplomats but others in positions of power and influence. It explains in its brochure the diplomatic protocol programme: “Protocol is a set of codes and rules that we can hardly ignore in diplomatic practice,” it says. “In recent years, the CEDS has implemented protocol training for diplomats and for senior executives and military officers. The ‘Diplomatic Protocol’ program is aimed at delegations of specific audiences, and covers a wide range of subjects such as the status of diplomats, immunities, accreditations and rules of precedence. It also teaches adapting the protocol to cultural diversity, but also to conflict situations, as well as to the context of multilateral diplomacy.” Successful candidates receive a certificate to prove they have been through the course.

CEDS is popular with military officers. After a career in the armed services, many of them seem keen to try applying their skills to diplomacy. First, though, they need training. “A general in the Lebanese army graduated with a PhD here,” Nohra told me, “and when he went back home he didn’t want to continue in purely military tasks. He created the Research Strategic Study Centre, the RSSC, for the Lebanese Army in 2011.” It is still a thriving institution. And he was not the only one: an alumni with the rank of colonel left the Belgian Air Force with similar goals because he was upset by what he saw as injustice and an unfair attitude among the great powers towards those that were weaker, and once he had returned to civilian life, he took to publicising his view in the mass media. See what a good education can do for you?

After all, preventing wars is one of the tasks of a diplomat, even one who was first trained to fight in them. “There are a lot of areas of study in diplomacy that are focusing on crisis management and conflict resolution,” said Nohra, “and this is very important because there are techniques in conflict resolution.” But diplomacy, he admits, is changing, too. “Non-official diplomacy has a big rôle [to play],” he says, “and now we talk a lot about ‘track 2 diplomacy’, where you have non-official people trying to change the mentality of the conflicting parties, the conflicting societies, to bring people to believe something different in order to allow the politicians to make a compromise.” That, of course, presupposes that the politicians in question are in a mood to compromise.

THE BLAME GAME

Diplomats, though, however diplomatic, are also human. Take the case of Sir Christopher Meyer, who was in the British diplomatic service for 36 years, during which time he spent more than 5 years as ambassador in Washington DC. He was popular with other diplomats and, according to the Irish Times, he was seen in Dublin as “a decent interlocutor”. Yet his memoirs, DC Confidential, published in 2005, led to questions being asked in the British Parliament and to the outrage of some politicians. The book has been “condemned by London’s great and good,” wrote The Irish Times, “He has been accused of disloyalty, vanity, financial greed and breach of trust. His critics say he has damaged the already threatened relationship between politicians and civil servants,” even though, as The Irish Times also notes, there are no shocking breaches of security, no great revelations, apart from Sir Christopher’s frequent observations that he was first attracted to Lady Meyer by her legs, which he apparently admired. Perhaps other governments and their ambassadors should note another of Sir Christopher’s observations, that “only the governments of Israel, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia and Ireland have, consistently over recent years, shown the ability significantly to influence the direction of US foreign policy.”

British former diplomat © Wikipedia

Influence is important. While Trump seems to attach most importance to ensuring his diplomats are ‘disruptive’, China has been trying to attract positive responses. According to the Observer Research Foundation, “Since 2012, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, Xi Jinping, has been calling on various Chinese agencies and experts in public diplomacy to ‘tell China stories well’ to the world, and ‘present a true, multidimensional and panoramic view of China’.” Beijing and Washington are, on the subject of diplomacy as in so many other areas, a long way apart. Nohra also notes the problems faced by the Ivory Coast between 2000 and 2011, when leaders blamed economic problems on some of the people of different ethnicity who were assumed not to be genuine Ivorians. Doing this whipped up ethnic hatred, suggesting the government’s failings were their fault. He still has great fondness for the country, however, and says the blame for demonising immigrants was the fault of the country’s leaders before 1994. But for Europe’s and the West’s turn towards populism and simplistic solutions, he blames the financial crisis of 2008. He is reluctant to name countries or point the finger of blame at particular politicians – he is, after all, a diplomatic man – but in this case he makes an exception. “Take the case of Hungary,” he says. “Hungary was ultra-liberal before the crisis, but finally the nationalistic and religious speeches of the new leaders came as a backlash against the crisis that hit the country very severely in 2009.” It got worse. “When there is a stable inter-dependency everything is fine, but when the global system reached a crisis this triggered a move towards separatism.” However, that is a vicious circle, “because the more you’re in crisis the more you search for false solutions, for kneejerk solutions, and the more you apply these types of solution, the deeper you are drawn into crisis and you end up being completely destroyed.” Leaders facing problems of their own making or problems they are unable to solve look for scapegoats, who are then sacrificed to legitimise a new social order.

Turning a population – or at least a sufficiently large percentage of it – into believing that outsiders are to blame for a country’s woes is an old trick. It has been going on for centuries. Nohra is not surprised by this. “There is no reason why a European country should not live through the same experience as the Ivory Coast did 20 years ago. I think this is universal and we always believe that we are more advanced and that ‘we will never have this’, ‘we will never have that’, but nobody knows.” Nohra says that when people are disappointed because whatever is happening is not what they imagined or wanted, they can turn against the very bodies that brought them human rights and the rule of law, such as the Council of Europe, the Court of Human Rights and European Union standards.

Nohra mentioned how quickly the far right can take advantage of public disappointment to sweep to power. Before the Brazilian election that brought the far-right Jair Messias Bolsonaro to power, Brazil had been demonstrating its successful operation of participatory democracy in Porto Allegre, Rio de Janeiro and other large cities, even bringing French politicians over to study and learn. No-one expected the backlash that made Bolsonaro president. Don’t think it couldn’t happen in your own country. Don’t think it couldn’t happen in Europe; we already have some populist leaders. But the only way to prevent the world returning to the era of Fascism is for those who study the mechanisms closely – especially diplomats or those with diplomatic training and skills – to find ways to avoid that outcome. “We have been accustomed to think about systems in a state of stability,” says Nohra, “we have not developed enough theories on disruption. We need to have a better understanding of disruptive mechanisms.” He and his colleagues are working on it.

By Jim Gibbons

Click here to read the 2020 April edition of Europe Diplomatic Magazine