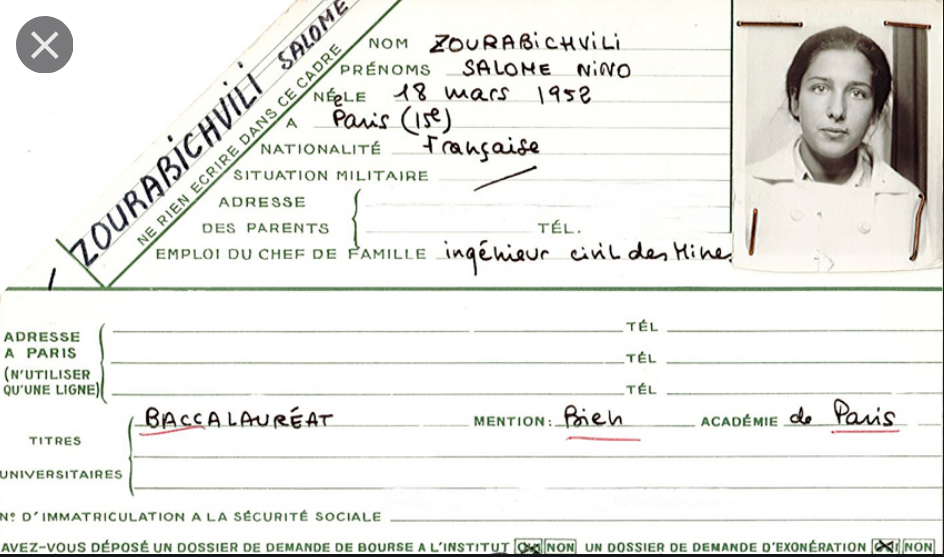

“In negotiating, the main force is to know which interests you are serving, that of the country and not a political line or personal career interests.” So says Salomé Zourabichvili, former French citizen and now President of Georgia, but who had joined the French diplomatic service in 1974 at the age of 22. Born in Paris of Georgian parents who had left their home country to escape Soviet Communism, she had wanted to serve Georgia’s best interests since her youth. So why through diplomacy? “I did not have an early vocation and cannot pretend that I from my early childhood had dreamt of becoming a diplomat,” she told me, “though when the time to choose the orientation of my studies came, I was thinking both in terms of which fields were attractive to me – history, journalism, writing – and what would be useful to the country which my family had left.” She and her parents had always believed that Georgia would regain its independence. “We firmly believed that the question indeed was ‘when’ and not ‘if’.” So, French was her first language, the Georgian came later and some commentators note that she still makes occasional linguistic errors in what is, after all, her native tongue (and a notably difficult one), but they hardly matter. “It gradually became clear that diplomacy was the answer to what would be the most immediate need for a country in order to reoccupy its place in the world community,” she said.

Zourabichvili’s father, an engineer who died in 1975, had been a prominent figure in the Georgian diaspora then living in Paris. Both of her parents had been descended from prominent political figures of the past, such as her paternal great-grandfather, Niko Nikoladze, a late nineteenth century social democrat, while her mother was related by marriage to Noe Ramishvili, the Democratic Republic of Georgia’s first prime minister. Zourabichvili was educated at some of the top schools in France, including the prestigious Institute d’Études Politique de Paris, and started reading for a Master’s degree at Columbia University in New York, where she studied under various luminaries including Zbigniew Brzezinski, who had been a counsellor to US President Lyndon B. Johnson and who later became National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter. There is a further link to academia: Zourabichvili’s cousin, Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, is a Franco-Georgian historian who heads the Académie française. Zorabichvili was married to Georgian journalist Janri Kashia, who died in 2012, and has two children from her first marriage, to the Iranian-American economist, Nicolas Gorjestani.

Zourabichvili has some distinguished antecedents. “Later on, I learned that I had an ambassador among my ancestors and that at the beginning of the 20th century, my great-grandfather had been leading the peace negotiations with Turkey at the time of the first Georgian Independence.” Even so, diplomacy was not an inevitable career choice for Zourabichvili. She faced a range of options. “The decision to turn to diplomacy came later when during an internship in the UN in New York, I came in contact with some diplomats of the French Permanent Representation, in which I would work years later, and was told that the French diplomatic career was finally opening up to women and that the time was right to enter this career.” So she did.

of States Colin Powell in 2004

© Wikipedia.

A LONG ROAD HOME?

During her years as a French diplomat she had postings to Rome, the United Nations, Brussels and Washington. She only visited Georgia for the first time in 1986, during a holiday from the French mission in Washington. That was to prove the beginning of a big career change for Zourabichvili. “I started as a French diplomat in 1974, 30 years later I was the French Ambassador to Georgia, which marked the end of my French diplomatic career and the beginning of a new Georgian life, when I accepted the offer to become the Foreign Minister of Georgia.” To do that, she had to change her official nationality in an agreement between Paris and Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, signed in 2004.

She became known as a tough negotiator. During her time in Georgia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, she successfully negotiated a treaty that led to the withdrawal of Russian forces from those parts of Georgia that – unlike Abkhazia and South Ossetia – are not in dispute. “A strong national consensus is a must for a successful negotiation,” she said. But having the Georgian people on her side was just part of it. “Also important in that specific negotiation, was my French background, which meant that my Russian counterpart, rather than looking at me with the old neo-colonial condescending attitude, had to accept me as an equal that he spoke to in English rather than in Russian, as was the practice with all old ex-Soviet sphere countries.” Zourabichvili is not a person one should talk down to. So, what was it that persuaded the Russian negotiator to give ground? “In the end, the most important was probably clarity in the objectives, and the right tone – neither confrontation nor subordination. However difficult the object of the negotiation and its context, however uneven the ‘rapport de forces’, there has to be some form of minimal trust between the negotiators, for the words and the written agreements to have a meaning. I think we managed that.”

That being said, Russia still holds sway over the breakaway, pro-Moscow regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and tensions remain with troop build-ups and occasional sabre-rattling. Abkhazia is a large region in the west of Georgia, but widely recognised by the international community to be a part of it. It borders Russia to the north and the Black Sea to its south and west. South Ossetia, half way along Georgia’s northern border with Russia, has always been seen as part of Georgia. That well-known Georgian, Yosif Visarionovich Stalin, confirmed South Ossetia’s status, which in so doing he supposedly regarded as a “gift” to his own homeland, even though it always had been part of Georgia. In fact, he was dividing Georgia. Historically, it had been a part of the Kingdom of Iberia in ancient times, of the Kingdom of Georgia in the Middle Ages, of the Kingdom of Kartli until the 19thcentury, and of the Democratic Republic of Georgia in 1918-1921, until the establishment of the Soviet Union.

Referring to the current tensions, Thomas de Waal wrote “This is a great and avoidable tragedy, as for centuries Georgians and Ossetians have lived together and there are still many mixed marriages.” De Waal, a senior fellow with Carnegie Europe, specializing in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region, was writing in the Moscow Times in 2019. “Present-day South Ossetia holds almost no value for Moscow, except as a military base close to the heart of Georgia.” But that is all it needs to be, perhaps, for a Russian government that can’t afford to be seen to lose face. Georgians living in Abkhazia’s Gali region used to travel backwards and forwards across the border into areas under Tbilisi’s control but it’s not a very secure existence. Last year, what pass for authorities in Abkhazia closed the bridge over the Inguria River, effectively preventing locals from visiting relatives or going to work. According to de Waal, “In normal times, around 3,000 people a day cross back and forth. Foreigners were also forbidden to cross into Abkhaz territory.” This, it’s suggested, is just the politics of bullying and nothing to do with security as some Abkhazians claim. “The pretext — alleged security concerns due to the recent opposition protests in Georgian cities — makes no sense. The de facto border is heavily guarded by both Russian and Abkhaz military personnel. This was a political move, a gesture of support for Moscow in its row with Tbilisi.”

FROZEN CONFLICTS

The two breakaway territories are home to separate indigenous peoples who enjoyed a certain amount of autonomy back in the days when Georgia was part of the Soviet Union. They do not see eye-to-eye on most things but they present a headache to whoever rules Georgia. “One thing is clear,” Zourabichvili told me, “that we do not have any means, nor the will, to try and resolve the conflict other than by peaceful means. That is why Georgia has taken a unilateral stance of renouncing the use of force in order to solve the conflict.” One could uncharitably point out that against an army the size of Russia’s, going to war would be tantamount to suicide anyway. But wars were fought over the territories as the Soviet Union broke up in the 1990s and again in the “5-day war” of 2008. In South Ossetia, it’s estimated that Russian troops, border guards and FSB agents outnumber the few Georgians still living there, and indeed the entire population has shrunk dramatically, while Abkhazians still remember the war of 1992 to 93, when it’s thought some 5% of them may have lost their lives. They, it seems, still see Moscow as preferable to Tbilisi. But an awful lot of the problem stems from Vladimir Putin’s expansionist policies as he appears to be trying to reassemble the Soviet Union with himself as leader. “Lacking direct diplomatic relations,” says Zourabichvili, “we are counting on our partners and asking them to recall to Russia its commitments of the 2008 cease fire agreement and make her finally understand that she has more to gain by the development of peaceful relations in her neighbourhood rather than through the perpetuation of tensions and occupations, which can only fuel instability.”

As far as Abkhazia is concerned, some outsiders see the risk as not so much annexation by Moscow as likely abandonment. Russia would gain nothing by taking it over. The place needs help with various things, including environmental degradation, and would like international help. However, it wants no help from Georgia. Georgia, however, has just taken over the Presidency of the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers for the first time. That is why Salomé Zourabichvili visited the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council in Strasbourg and addressed the members. “This is for us an important responsibility and a wonderful opportunity at the same time,” she told the Assembly, “Yesterday our foreign minister presented our priorities during this presidency: human rights and environmental protection, a very new and important endeavour; civil participation in decision making processes, the next stage of democracy; child-friendly justice, converging experiences on the restorative justice; and strengthening democracy through education, culture and youth engagement. Those four priorities are those we are going to work on all together. They were selected to reflect the challenges that are faced by all societies today and I intend to launch a comprehensive discussion on possible solutions.”

Mikhail Saakashvili in 2008

Zourabichvili sees the creation of the Council of Europe in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War as a vital step towards more harmonized attitudes and standards, when it comes to respecting individual citizens. “The adoption of the European Convention on Human Rights laid the ground for the organisation and became the guideline for each and every member. Democracy, human rights and rule of law became the core principles that we all need to adhere to and to be guided by,” she told the Assembly. “I strongly believe, especially today, even more today, that each and every member of the Council of Europe should abide by the values and principles of the organisation.” It’s true that the Council of Europe has forty-seven member states which try – not always successfully – to get on with one another. It’s worth remembering that the 12-star flag of Europe was originally created as a logo for the Council in 1955, the result of a competition that attracted hundreds of suggestions. It was only thirty years later that it was adopted by the EU institutions and even then, not by all of them at the same time. It is not, and never has been, just the flag of the European Union. You will find it being flown in all of the Council’s member countries, although possibly not in the United Kingdom, where it seems indissolubly linked in the public mind (and the minds of government politicians) with Brussels. In Georgia’s case, though, Council membership remains a matter of national pride, as Zourabichvili mentioned in her speech to the Assembly: “Georgia celebrated 20 years of membership last year. It had recovered independence from Soviet rule just 12 years before that. Today it is indeed difficult to imagine where we were and how fast what one can call a revolution has happened. We have come a long way.”

MOVING ON

Georgia certainly has. As the Soviet Union began to come apart, a wave of inter-ethnic violence swept through the Caucasus to the west of the Caspian Sea, with conflict flaring up among the wide variety of ethnic groups. Some were Christian, such as the Georgians, Armenians and Ossetians, some, such as the Circassians, Chechens, and various Turkic-speakers, were Muslim. Under Soviet rule, these groups got on reasonably well or else ignored each other. But in Georgia, the election of ultra-nationalist Zviad Gamsakhurdia in 1991 launched suspicion, hatred and conflict. Supported by a very nationalist media, the rhetoric provoked outbreaks of violence, involving rival militias. Eventually, Georgia sent 6,000 troops to Tskhinvali, the de facto capital of separatist South Ossetia. Russia sent troops to keep the peace without taking sides. But tensions continued to worsen when a new Georgian President, Mikhail Saakashvili talked of integrating South Ossetia, an idea Putin has dismissed as ‘Stalinism’. Having promised the South Ossetians that they were safe, Saakashvili sent 1,500 troops to Tskhinvali. Russia used that as a pretext for invasion; Moscow subsequently recognized the independence of the Republic of South Ossetia. The region’s border with the rest of Georgia was closed. Even so, with no industry to speak of and with most of its agricultural output going to Russia, South Ossetia comfortably relies on Russian financial support, lacking the means to support itself. Unlike their Russian-speaking neighbours in North Ossetia, the South Ossetians speak an ancient east Iranian dialect, supposedly descended from the language of the Scythians. Languages divide so many people in the world who might otherwise be friends. Possibly.

It seems virtually impossible that the Georgians and South Ossetians will ever be reconciled but if South Ossetia were to be swallowed up by an expansionist Russia, a unique culture and ancient language could be lost. So, let’s talk about the politics of the possible. Zourabichvili made it clear in her speech to the Parliamentary Assembly that she wants to tackle some of the problems being increasingly recognised as global. “Environmental rights, more specifically protection of individuals and communities against environmental harm, is a priority that most countries are now learning how to deal with,” she said. “It is a UN Sustainable Development Goal that we all agreed beyond our continent. I believe that caring about our planet requires joint efforts at every geographical, political or societal level. Therefore, it is no accident that Georgia chose human rights and environmental protection as one of its priorities for our presidency.”

HISTORIC GEORGIAN WOMEN

How difficult is it going to be during the 6-year term as President? Not easy, certainly; Zourabichvili is Georgia’s first woman President and politics in the region can be – how shall I put it? – robust. But she is undaunted, she told the Assembly. “As the first woman president of Georgia I am no exception in Georgian history, for Georgia has been a progressive country in gender equality for centuries,” she said, and with some justification. “We had women governing the country centuries ago and Georgia’s constitution in 1920 already ensured equal political rights for women not only to elect but to be elected. The first constituent assembly of Georgia had five women members, one of them the first Muslim woman to be elected.” Despite her country’s encouraging record on gender issues, I asked her if she had met with obstacles in her election campaign and, if so, how she had dealt with them. “In Georgian history women have had a specific place and have been recognized for their role,” she said, “St Nino came to Georgia and converted the Georgian state and monarchy to Christianity 1,700 years ago. Queen (but called King) Thamar reigned at the time of biggest prosperity and largest expansion of the Georgian Kingdom; martyrs Shushanik and Kethevan are part of the Georgian History of resisting foreign faith and occupation. In our more recent history, Georgian women were fully party to the national emancipation movement that led to the independence in 1918 and they gained naturally the right to elect and be elected, recognized in the first constitution. So, the election of a woman as President, unusual in the region is not such an exceptional event for the Georgian society and was not opposed so much on gender grounds.”

In fact, the election campaign was at times quite vicious and some of the attacks made on Zourabichvili were undoubtedly gender-based. They certainly didn’t put her off or lead to her defeat, however. She believes the Georgian people are proud to have a woman president. After all, they still remember Shushanik (a Christian Armenian woman tortured to death in Georgia by her husband in the 5th century) and Kethevan (a queen of Kakheti in eastern Georgia, killed after torture for refusing to convert to Islam). Georgian women have had a tough time down the years. Zourabichvili is determined that things will be fairer for them in the future. In her speech in Strasbourg she said: “My personal duty is to promote and encourage equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women at every level of society in every part of Georgia. Unfortunately, the need to safeguard women from violence at home or elsewhere has appeared in recent years, even in Georgia, which seemed immune to such excesses. But drastic social changes and economic hardship have taken their toll, and families have been giving in to the spiral of domestic abuse and violence.” She stressed the importance of the Council of Europe’s Convention against gender violence: “The Istanbul Convention sets high standards for preventing violence, protection of victims and most importantly, prosecuting accused offenders. This will be at the centre of my attention to see that it is implemented without complacency or hesitation.”

The path to power wasn’t an easy one, and of its type, it will be the last. In future, presidents will be chosen by an electoral college and not by universal suffrage. Zourabichvili is the first woman president and the last to be directly elected. She is, incidentally, the fifth president of an independent Georgia. Not long after accepting Georgian citizenship and becoming Minister of Foreign Affairs, she fell out with the country’s then president, Mikheil Saakashvili. Zourabichvili was sacked by the then Prime Minister, Zurab Nogaideli in October 2005 after rows with some members of Parliament and after coming in for criticism from certain Georgian ambassadors. Just before her sacking, she finally resigned from the French diplomatic service which had continued to pay her salary. She said she would go into politics and she did. In 2006, she founded a new political party, called ‘The Way of Georgia’, which she led until 2010. In 2016, she was elected to the Georgian parliament as an independent. It was never likely to be plain sailing. In the 2018 campaign for the Presidency, Zourabichvili ran as an independent, but with the support of the Georgian Dream party, which was in power. She failed to win outright, getting just 38.7% of the vote in the first round, but secured the Presidency in a run-off against Grigol Vashadze, who had the backing of Mikheil Saakashvili.

IT ALL COMES DOWN TO DIPLOMACY

And what about that diplomatic background? I asked her if had been helpful in her political career. “I think that the diplomatic background has definitely served and enlightened my political career,” she said. “In the three stages of my political life – as Foreign Minister, Member of Parliament and now President – the diplomatic experience, the knowledge of the outside world and its rules and practices, as well as my European background, have helped me in better representing Georgia, better defending its interests, better understanding the regional or international challenges, better deciphering the objectives of our partners.” She has also had the benefit of having worked within a lot of major international organisations, such as the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), NATO and the United Nations, not to mention the fifteen years she spent working in the United States. It has proved invaluable experience; wherever she goes in the world on Georgia’s behalf, many of the people in power know her.

Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg © Nato

Zourabichvili sees herself as being in a position to provide a platform to help reduce tensions between faiths, although that’s more an accident of Georgian history than a personal achievement. As she told the Parliamentary Assembly, “We have districts, not only in the capital Tbilisi, but also in Kutaisi and many other cities, where Orthodox, Catholic, Armenian Gregorian churches, synagogues and mosques are built next to each other and where people continue to practice their religion in pure coexistence.” She pointed out one unexpected example of inter-faith tolerance, unique to Georgia: “The Tbilisi mosque is quite exceptional since it is the only one today where Shia and Sunni Muslims pray together. This traditional tolerance and coexistence are still very much a reality and have not been overshadowed or limited by the distressed isolation or aggression that we see today in the outside world.”

She hopes that this peace-making role can be extended beyond religion, based on Georgia’s long tradition of being home to so many different races and ethnic groups. “Georgia is among the countries that grant full linguistic, cultural and religious rights to the national minorities living on our territory,” she told the Assembly. “We have coexisted for centuries. This diversity is an integral part of Georgia’s socio-economic development. These minorities enjoy full rights to their language, to their culture, to their traditions. To such an extent, and that is maybe part of the problem, that a majority of these national minorities do not speak the state language, and that is an obstacle to promotion. That is an issue that I consider to be my personal competence and duty, to ameliorate and to promote these efforts towards better and fuller integration.” If anyone ever wants to see the damage that ethnic, linguistic and religious divisions can cause, they should have a stroll around Belfast in Northern Ireland, where the streets are disfigured by so-called ‘peace walls’ to keep republicans and loyalists apart and to discourage violence. One Sinn Féin councilor happily related to me tales of “recreational violence” in his youth. And he was a good, pleasant man. Yet still the groups disagree over religion, the use of the Irish language and their own history. Georgia seems determined to avoid such an outcome; I wish it luck.

© president.gov.ge

Zourabichvili hopes her long career as a diplomat will help her to achieve the sort of future she wants for Georgia, although in politics nothing is ever certain. “Diplomacy can help resolve issues not only in international relations but also within countries,” she said. “Today when we are all confronted with increased polarization, distrust, extremism and populism, all in the end reducing our freedom, it is urgent to reconstruct our societies around some elements of unity. Diplomacy can help find these common elements, can help to create the channels for discussion and avoid isolation and lack of communication that are more and more characterizing our contemporary societies. Diplomacy is not a panacea, but can be a useful instrument if we know what we want in the end and in what direction we are going.”

IMPROVING CITIZENS’ RIGHTS

Zourabichvili hopes that the direction is the right one, although in her speech to the Assembly she conceded that there is still more to be done. She cited the example of a national human rights strategy and action plan, which was launched in 2014 and is due to reach its conclusion this year. A recent evaluation by EU and UN officials welcomes, as she put it, “the significant progress, to greater or lesser degrees, in almost all of the specific subject areas addressed in the strategy.” So, there is still a way to go. “Though the number of implemented recommendations is growing there is certainly room for improvement and more implementation of these recommendations. From its own monitoring perspective, the parliament has gained expanded oversight functions under the new constitution that should be and are partly actively applied.”

Certainly, we live in strange times. Not so long ago, Europe seemed to be heading for further integration to make conflict less likely and peoples more comfortable with each other, just as Georgia is doing. Then along came the populists with their own agendas aimed at furthering their personal ambitions without regard to others and seemingly without regard to relations with their neighbours. Take Poland, for example, whose reforms to its justice system have brought heavy criticism from the Venice Commission, the European Court of Human Rights and the European Commission. Effectively, Poland’s government wants to appoint justices, have the right to move them to other courts and even re-open closed cases, opening the way for what are called “double jeopardy” prosecutions. They are also combining the roles of Minister of Justice and Chief Prosecutor, in clear breach of their obligations under the European Convention of Human Rights and of their membership of the European Union. The concern over Poland’s judicial reforms was raised at the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly by Dutch Christian Democrat MP Pieter Omtzigt, who admitted that Poland’s ruling party has friends, or at least one friend: Hungary. Populists stick together. “The European Commission has opened Article 7 proceedings,” he told me, “but they can be defeated by one other country, so they will not go much further.” The rules were not designed to cope with rebels nobody expected but who back each other’s excesses and misdeeds.

In the end, sorting out all these sorts of problems comes down to diplomacy; you could say that there was never a time in Europe’s post-war history when diplomacy was more necessary. Certainly, Salomé Zourabichvili thinks it could provide a future for young people wanting to be at the heart of things. “It is certainly a very attractive career,” she said, “especially in a world that is changing very fast, where challenges are multiplying, and trying to fight them and limit their effects is a noble task. Understanding the differences and the other in a world where people tend to want to ignore others and are more tempted to close in rather than open up is vital.” We are entering a time of more closed borders, a rejection of the freedom of movement the European Union has long stood for and the Council of Europe espouses. “Global challenges will be confronted only if we find a common language and some common interests. And in the end the only known alternative to diplomacy being war, diplomacy still has a good future, even if today’s diplomacy does not have much in common with what it was a few decades ago, when I started my career. It is a much more demanding profession, which needs a good knowledge of all the new fields that make today’s world – economy, technology, science, communications together with culture, history and geography – a diplomat has to understand them all in order to be effective.” That’s a pretty tall order by any standard.

And diplomats will be increasingly in demand in this difficult and divided world. As the American journalist and writer Isaac Goldberg wrote:

“Diplomacy is to do and say

The nastiest thing in the nicest way.”

Or how about another American writer, Caskie Stinnet?:

“A diplomat… is a person who can tell you to go to hell in such a way that you actually look forward to the trip.”

But I leave the last word to Salomé Zourabichvili, despite the cynicism often expressed about the profession: the “qualities needed though have not changed: curiosity, interest towards others, sense of initiative, discretion and last but not least – a deep love for one’s own country.” You can’t argue with that, although in diplomatic circles someone undoubtedly will.

Jim Gibbons