A joint exercise with the French military aimed to evaluate various capabilities of the Chadian Air Operations Centre, including victim protection, the initiation of evacuation for the wounded, and the provision of medical care © defense.gouv

In the heart of Africa, a continent that has long felt the impact of colonial powers, we are witnessing a major transformation. As France struggles to maintain its historical ties and economic interests, Russia and China are stepping into the picture, poised to take advantage of France’s waning influence. This shift isn’t happening in isolation. Both Russia and China have their own agendas and ambitions, and they are keen to seize the opportunities created by France’s retreat. Take Russia, for instance: its military presence, highlighted by the activities of the Wagner Group, is making waves across the continent, while China is pouring resources into Africa through its Belt and Road Initiative, building infrastructure that could change the game for many nations. To fully understand the impact of France’s colonial relationships in Africa and the gradual disintegration of these ties, it is essential to place these complex legacies within a historical context.

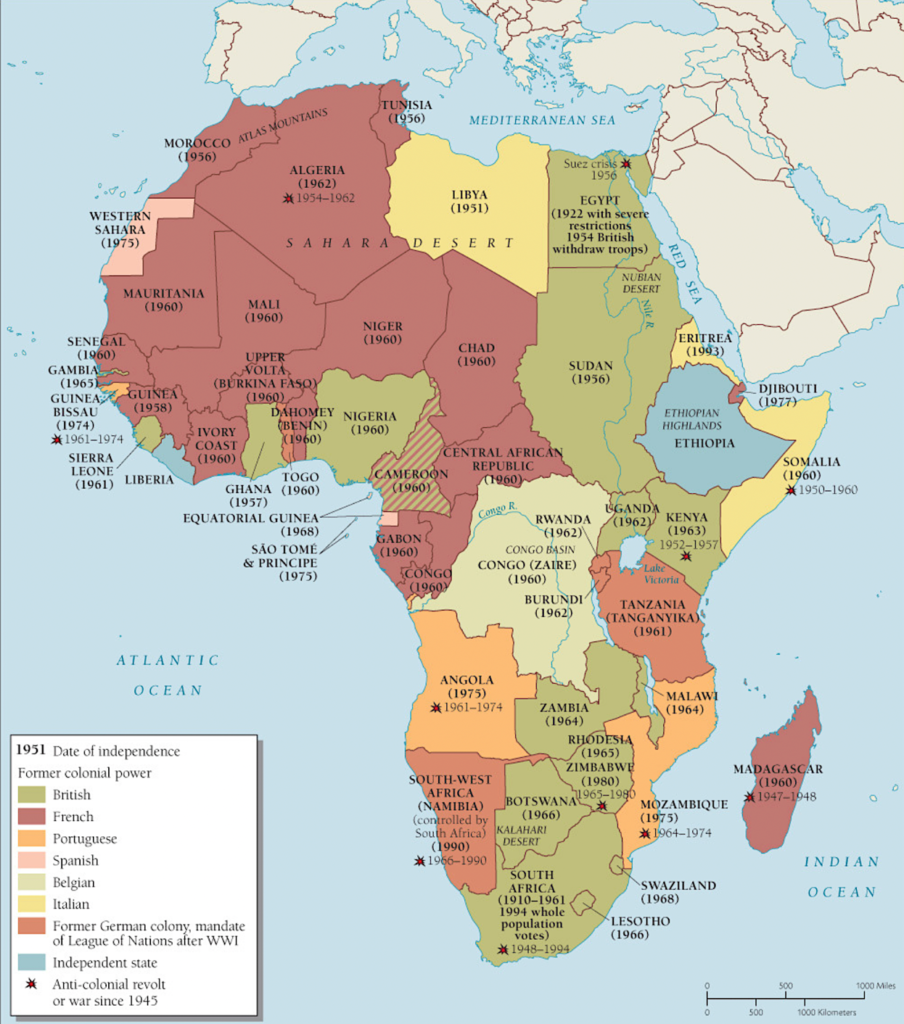

The term “Françafrique” captures the intricate web of connections between France and its former African colonies, a relationship that dates back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, during a time often referred to as the “Scramble for Africa”. This era was marked by intense competition among European powers for control of African territories, leading to significant and lasting impacts on the continent. At the heart of French colonialism in Africa was a distinctive policy known as assimilation, an approach that sought to integrate the colonies into the broader framework of French administrative and cultural systems. The French envisioned a “Greater France,” aspiring to extend not just territorial control but also French citizenship and cultural values to their colonies, so as to foster a sense of unity and identity that corresponded to their own national ideals.

French colonial influence was particularly pronounced in several key regions. Countries such as Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Benin, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mauritania were part of what was known as French West Africa. This vast region, rich in resources and diversity, contributed significantly to the French economy and cultural landscape. In Central Africa, the territories known as French Equatorial Africa included Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, and Chad. Each of these areas presented unique challenges and opportunities for the French, as they confronted the complexities of governance and cultural integration.

As we moved into the 1960s, a wave of decolonisation swept across the continent, with many former colonies finally achieving political independence. This was a hopeful period, as these nations sought to carve out their own identities and reclaim control over their governance. However, their relationship with France did not simply fade away; instead, it transformed into something more complex and, in many ways, more insidious—a form of neocolonialism. This shift represented a move away from direct colonial rule to a subtler, yet just as powerful system of influence. On the surface, these nations appeared to enjoy independence and sovereignty, but the reality was quite different.

Their political and economic systems were increasingly shaped by external forces, particularly by France, the very power they had sought to escape. And it was precisely due to the “Françafrique” system that a network of personal and political relationships remained active and ensured that France continued to play a dominant role in the region, primarily through its military presence which has been a cornerstone of its post-colonial influence. French military interventions, like Operation Serval in Mali (2013) and Operation Barkhane (2014), were launched with the goals of fighting Islamist terrorism and bringing stability to the region. But these efforts faced wide criticism for maintaining neocolonial influences and not tackling the underlying issues that fuel conflict.

| ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL TIES

France has maintained enduring economic relationships with its former colonies, rooted in extensive trade, investment, and development aid. These connections have evolved into a complex web of mutual interests, where French companies have made significant inroads into various sectors, including mining, energy, and infrastructure. This engagement not only bolsters the economies of these nations but also reinforces France’s presence and influence in the region.

A key element in this economic partnership is the CFA franc, used by several West and Central African countries. As this currency is pegged to the euro, it further strengthens economic ties between France and its former colonies. Culturally, France has actively promoted its language and values in these regions through institutions like the Alliance Française and various educational programmes. The French language continues to serve as an official language in many of these former colonies, acting as a bridge that connects diverse populations and cultures. Cultural exchanges, including art, literature, and music, serve to further enhance these ties.

However, the growing presence of other global powers, including Russia and China has introduced new dynamics, leading to some shifts in allegiances and partnerships; these have affected the very nature of French influence and aid in these regions.

In a recent, and very significant move aimed at further distancing themselves from their former colonial ruler, Niger’s military leaders have been changing street and monument names that previously honoured French figures. Avenue Charles de Gaulle in the capital, Niamey, has been renamed Avenue Djibo Bakary, paying tribute to the politician who was instrumental in Niger’s fight for independence in 1960.

Another site in Niamey that has been modified is a stone monument that once featured an engraving of French colonial officer and explorer Parfait-Louis Monteil. Colonel Monteil journeyed from Senegal to Libya in 1890, crossing West Africa and documenting his two-year expedition in a book. His image on the monument has now been replaced with a portrait of Burkina Faso’s iconic revolutionary leader, Thomas Sankara who was assassinated in 1987. During his time in power, Sankara implemented an anti-imperialist foreign policy that directly challenged France’s dominance, significantly influencing many of its former colonies in Africa.

Two of Niger’s western neighbours, Mali and Burkina Faso — both former French colonies — have similarly turned to Russia for military support in their fight against the jihadist insurgency that is threatening the region. These three countries have joined forces, forming an alliance they refer to as the Alliance of Sahel States.

A large square in Niamey called Place de la Francophonie, named after the group of French-speaking nations also saw its name changed to Place de l’Alliance des États du Sahel after the country’s new confederation with Mali and Burkina Faso.

| RUSSIA STEPS IN

Russia’s growing involvement in African nations today looks like a mirror image of the Soviet Union’s old partnerships with the newly independent former French colonies. This connection really started to flourish in the late 1950s and continued to thrive through the 1960s and 1970s, a time when many African countries were breaking free from colonial rule.

Back then, the Soviet Union was eager to connect with these emerging nations, offering economic assistance and support as part of a broader strategy to push back against Western influence, particularly from the United States and older colonial powers like France and the UK. It was all about positioning themselves as allies in the struggle against imperialism.

Fast forward to today, and we see Russia restoring those historical ties with fresh enthusiasm. This modern approach focuses on creating economic partnerships, military cooperation, and political alliances, all aimed at reclaiming influence in a region of great importance. For Russia, engaging with African nations isn’t just a trip down memory lane; it’s a strategic move to reassert its presence on the global stage.

Just like the Soviets back in the day, Russia is emphasising resource deals, military agreements, and infrastructure projects, presenting these efforts as support for Africa’s growth and self-determination. This narrative resonates with many African leaders who are seeking alternatives to Western influence, which often comes with its own challenges.

In many ways, Russia’s current efforts reflect those historical ties, blending the past with today’s geopolitical strategies. By reaching out to Africa, Russia hopes to present itself as a reliable partner, illustrating the complexities of international relations in a world still grappling with the legacies of colonialism and the ongoing quest for genuine independence.

In a more subtle and perhaps troubling fashion, Russia is using media and cultural initiatives to draw in African journalists, influencers, and students while simultaneously disseminating misleading information. This strategy reflects a calculated effort to reshape narratives and create connections that align with Russian interests. Central to this mission is a recently-established Russian media organisation called African Initiative which positions itself as an “information bridge between Russia and Africa.” The organisation has inherited structures from the now-defunct Wagner mercenary group, and according to experts, probably has ties to the Russian security services, hinting at deeper motivations behind its operations.

The African Initiative was registered in September 2023, one month after the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin in a plane crash. Since then, it has actively recruited former employees from Prigozhin’s disbanded enterprises, suggesting that this continuity is a strategic shift rather than a complete break from past practices. This is evidenced by the Africa Corps , also known as the Russian Expeditionary Corps (REK), established by Russia’s defence ministry in order to take over the military functions previously held by Wagner in West Africa.

As for African Initiative, the organisation’s efforts have been particularly concentrated in three military-led, former French colonies — Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso — where political dynamics are complex and often unstable. Russia’s approach aims to capitalise on existing sentiments and bring about alliances that could reshape the region’s geopolitical landscape and allow Russia to establish a foothold.

| GROWING MILITARY INFLUENCE

The changing landscape of international influence in Africa has become very clear, especially in the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali. In these countries, the Russian military and remnants of the Wagner Group, now known as the Africa Corps, have gradually replaced the long-standing French military presence and economic support. This shift reflects a larger change in global power dynamics, with new alliances forming and strategies evolving.

Russian companies have secured profitable contracts in the mining sector, particularly for diamonds and gold, often with the backing of the military, providing security for Russian interests. The economic advantages for the CAR government, along with military support, made the Russian presence more appealing compared to French aid, which was often viewed as too conditional.

A similar situation occurred in Mali where France had been a crucial ally, offering military support to fight Islamist insurgents. However, the introduction of the Wagner Group, followed by the Africa Corps and Russian military advisors changed the dynamics. These elements adopted a more aggressive approach to dealing with insurgents, which some considered more effective in the short term. On top of this, allegations of human rights abuses by French forces led to a growing preference for Russian involvement in the country.

But it must also be said that wherever the Russian paramilitary and mercenary forces deploy, a significant rise in civilian deaths follow. Reports indicate that Wagner forces have engaged in horrific acts, including the destruction of entire villages and the killing of civilians in the CAR, unlawful executions in Mali and raids on artisanal gold mines.

Data from The Economist and the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), which is an independent, international non-profit organisation collecting data on violent conflict and protest in all countries in the world, indicate that violence against civilians by Wagner in Mali and the CAR is alarmingly frequent and deadlier than attacks by state or rebel forces.

As of August 2023, Wagner has been responsible for the deaths of at least 1,800 African civilians. While Wagner claims to be promoting “peace and stability” in Africa, the reality is stark: in Mali, terrorist violence against civilians has surged by 278 percent since 2021.

The changes happening in the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali show how military, economic, and diplomatic factors are all connected. By offering military support and resources, the Russian military, the Wagner Group and the Africa Corps have effectively presented themselves as credible alternatives to traditional French aid, providing a blend of security and economic development that appeals to local governments; they help in keeping authoritarian leaders in power, often quashing dissent and eliminating opposition.

This quid pro quo approach has allowed Russia to expand its influence and challenge Western dominance in the region, ultimately reshaping the geopolitical landscape.

| ANNUS HORRIBILIS

2023 was a year during which France’s influence in Africa experienced a significant decline, when the French embassy in Niger closed, ending diplomatic services in the West African country. But despite this negative outcome, France continues to maintain a military presence in several key African nations, including Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Gabon, Djibouti, and Chad. However, this event was a major blow, accelerating France’s waning influence over its former colonies and significantly diminishing its standing.

In February 2023, French troops left Burkina Faso amid a climate of deteriorating relations, caused mainly by the coup that brought Captain Ibrahim Traoré to power in Burkina Faso in 2022. This exit followed the withdrawal of France’s 4,500-strong Operation Barkhane force from Mali in August 2022.

Throughout that year, the political context in Ouagadougou shifted significantly, with the government signing new partnerships with Russia. One of the most important developments was an agreement on the construction of a nuclear power plant in Burkina Faso. In November 2022, the arrival of a Russian military aircraft at the Thomas Sankara airport underlined this new alliance, as it reportedly carried private mercenaries from the newly- formed Africa Corps, which includes a substantial number of former Wagner Group paramilitary personnel.

In March, the Malian government took a significant step by suspending the operations of French media within the country. This decision came as relations between Mali and France had already been strained for some time. The tension had started in 2020, when Colonel Assimi Goita led a military coup that overthrew President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, who had been backed by France.

The government specifically targeted state-run French media outlets, RFI and France 24, accusing them of broadcasting false reports about the humanitarian situation in Mali. This decision was seen as a reaction to the perceived negative portrayal of the country in the French media. Just a few weeks later, in April, Mali’s media regulatory body took the situation a step further and made the suspension a permanent ban, bringing about a serious deterioration in diplomatic ties between the two nations.

In July, a military coup led by General Abdourahman Tchiani ousted Niger’s President Mohammed Bazoum, forcing Paris to close its embassy and officially suspend relations with Niamey. This situation was troubling for Paris, which had increasingly looked to Niger as a key ally in the Sahel, especially after its influence in Mali and Burkina Faso waned.

In 2022, many of the troops that were pulled out of Mali were relocated to Niger, where France also maintained one of its largest military bases on the continent.

In September, France announced a freeze on new visa applications for students from Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, citing deteriorating security relations with the military-led governments in those countries. While this decision does not affect students currently in France or those with valid visas, it significantly impacts those hoping to study abroad or renew their visas. Many of these prospective students were expecting to benefit from French development aid for their studies, which has now also been cut off.

This decision also extends to artists, reflecting a broader trend of distancing from these countries.

On 2 December, Niger and Burkina Faso announced their withdrawal from the G5 Sahel, a multinational military alliance formed to combat armed groups in the unstable Sahel region. Established in 2014, the G5 initially included five nations and was bolstered by a counterinsurgency force supported by France in 2017.

However, due to strained relations with the military governments of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, the alliance has struggled to remain effective, leading to criticism over its inability to bring lasting peace to the area. With Mali already out, the future of the G5 is uncertain, leaving Chad and Mauritania as the only remaining members.

On 25 December, Nigerien authorities announced they were suspending all cooperation with the International Organisation of Francophone Nations, based in Paris, which promotes French language and culture. This organisation had already limited its relations with Niamey following the July coup. The Nigerien military government claimed that the 88-member organisation was being “used by France as an instrument to defend French interests.”

| URANIUM SPARKS FRESH TENSIONS

On 7 December 2024, in a striking turn of events, the relationship between Niger and France took another dramatic downturn, with Niger’s military leaders seemingly determined in their decision to exclude France from any significant role in their economy—particularly in the field of uranium mining.

The state-owned French nuclear company Orano, announced that the military junta that ousted former President Mohamed Bazoum, has taken over operational control over the local mining firm, Somair, and that decisions made during board meetings are no longer being implemented.

Orano holds about 63% of the Somair mine, with Niger owning the remainder. In June 2024, a crucial mining permit was revoked, leading to export blockades that halted shipments. As a result of these disruptions, 1,150 tons of uranium concentrate were stranded, and the company faced losses exceeding $200 million. By October, operations had completely stopped due to financial and logistical challenges. Now, Orano has confirmed that it has lost all operational control of the mine.

For French President Emmanuel Macron, the timing of this event is something of a public relations nightmare and quite awkward in image terms, especially in light of the political crisis at home, as well as other unwelcome developments in Africa.

Chad has unexpectedly ended its defence agreement with France, and Senegal has reaffirmed its plan to close the French military base in Dakar. Meanwhile, Orano’s crisis in Niger poses a significant practical problem for France’s energy supply. This is a complex situation with multiple moving parts, but the key takeaway is that France is facing challenges on multiple fronts in Africa and at home.

France operates 18 nuclear plants that generate nearly 65% of its electricity. However, the country stopped producing its own uranium over 20 years ago, and in the past decade, it has imported nearly 90,000 tonnes of uranium, with about 20% coming from Niger.

For years, Orano’s dominant position in the uranium sector fuelled resentment among many Nigeriens. They claimed the company was buying uranium at unfairly low prices, and although mining operations began years after Niger’s independence, they were seen as symbols of France’s lingering post-colonial influence.

The current situation doesn’t just affect the French company; it also hurts Niger’s economy, which will have to deal with the loss of export earnings and hundreds of jobs. But there is one entity that is ready to step in and offer assistance, especially in the economic field, not only to Niger but many other African nations going through difficult times.

| CHINESE ECONOMIC POWER

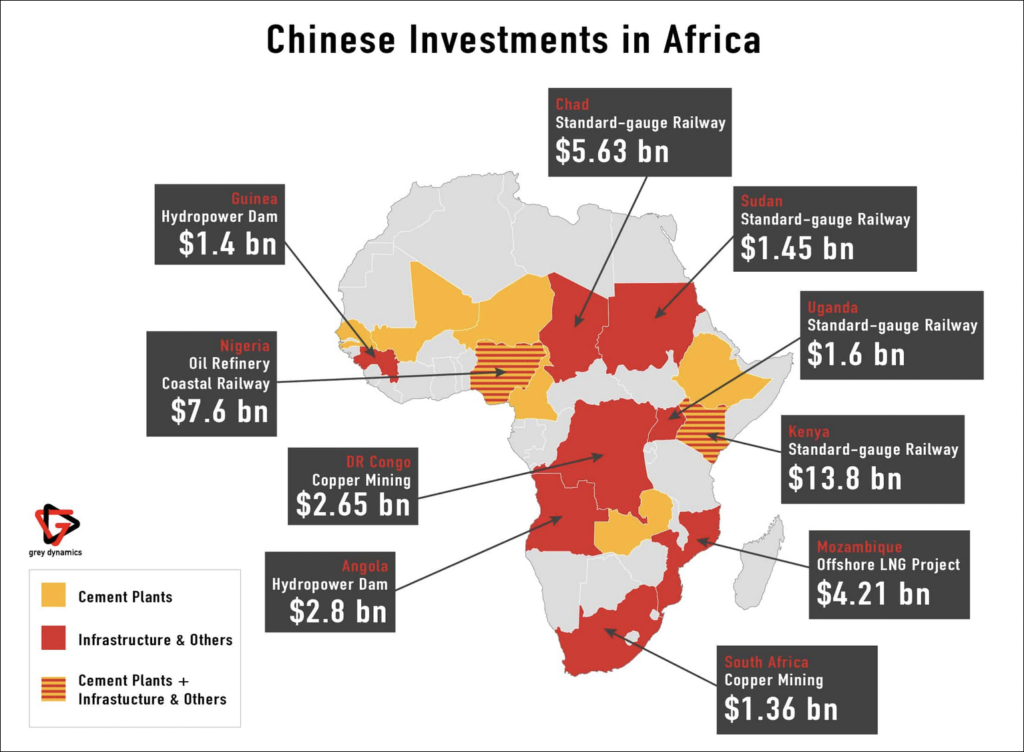

Over the past two decades, China’s presence in Africa has expanded dramatically, largely fuelled by its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and a strategic emphasis on economic diplomacy. As a result, China has emerged as a major investor and trading partner for numerous African countries, focusing its efforts on key sectors such as infrastructure, mining, and energy.

The BRI has been a game changer, channeling billions of dollars into African infrastructure projects, including vital roads, railways, and ports. Many African governments have embraced these investments, viewing them as essential for driving economic growth and modernization. However, this rapid influx of Chinese capital has sparked concerns among critics regarding debt sustainability and the potential for an overreliance on Chinese economic influence.

What sets China’s approach apart is its policy of non-interference in the internal affairs of African nations. This stance has made China a particularly attractive partner for many African governments, allowing for the establishment of strong diplomatic and economic ties. As a result, China’s growing influence often comes at the expense of traditional Western powers, reshaping the geopolitical landscape of the continent.

| A NEW GEOPOLITICAL CHESSBOARD: FRANCE, RUSSIA, CHINA

Once firmly under French influence, huge swathes of the African continent are now a battleground for competing powers like Russia and China. This shift brings both opportunities and challenges for the region.

For France, the implications are significant. Its historical ties to Africa have provided economic and political advantages, but declining influence means Paris must adapt to a new reality. The rise of Russia and China has diminished France’s traditional dominance, requiring a more careful approach to its relations with African nations.

African countries find themselves navigating a complex geopolitical landscape. While Russia and China offer economic opportunities and strategic partnerships, they also have their own agendas. The influx of investment from these countries often comes with unclear terms, raising concerns about debt sustainability and geopolitical risks. What’s more, the rivalry between these powers can worsen existing conflicts and destabilise vulnerable regions.

The challenges in this changing landscape are varied. For France, it’s about maintaining influence in a more competitive environment. For African nations, the challenge is to reap the benefits of new partnerships while managing the associated risks.

So, as the geopolitical chessboard evolves, Africa’s future will depend on every single move made by all the players involved.