Illustration of SARS-CoV-2 virus © Wikicommons

It was Hiram Johnson, a Progressive Republican from California, who is credited with stating that: “The first casualty, when war comes, is truth”. He said it during World War 1, and ironically, he died on 6 August 1945, the very day on which the United States dropped the first atomic bomb to be used in a war on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Now , it seems, the world is at war with a virus that is just 100 nanometres across (a nanometer is one billionth of a meter, 0.000000001 or 10-9 meters, so the virus measures on average 0.0000001 meters from side to side).

It’s called SARS-CoV-2 and it comes in several variant forms as it evolves (surprisingly rapidly) to survive the latest anti-viral treatment our cleverest virologists have devised. The most recent at the time of writing is the mu variant; I don’t know why. Not long ago everyone was talking about the delta variant. Delta is the fourth letter in the Greek alphabet, mu is the twelfth. So, what happened to epsilon, zeta, eta, theta, iota, kappa and lambda, then? Well, they seem to be less worrying. The delta variant is apparently more dangerous, or it may be. No-one is completely sure, and research is ongoing. It contains the N501S mutation, anyway, which is similar to the mutation in the alpha variant known as N501Y, first identified in the UK in 2020. Some dozen or so sub-mutations have also been noted around the world, probably accounting for the missing Greek letters. In any case, SARS-CoV-2 in its various versions is not going to leave us any time soon, unfortunately. At the time of writing, there have been 219-million cases worldwide so far, and 4.55-million deaths.

This is an indisputable fact, but in some countries, it has been increasingly difficult for the media to report it. Governments in Europe and across the world have effectively been taking control of the media trying to cover the story of the disease and its inexorable spread. In Serbia, according to the World Press Freedom index, a news website reporter, Ana Lalić was arrested at home late at night after covering the way a hospital was trying to cope with the virus.

By doing so, she had ignored a government decree that put all reporting about Covid-19 under the control of a government department that had been given the task of handling all information about the virus. Only government officials could talk about it or write about it. The press freedom campaigning group, Reporters Without Borders (RSF), similarly cites the case of Kosovo journalist Tatjana Lazarevic, who was arrested in the street while trying to cover the pandemic’s impact. Editor-in-chief of the online news portal KosSev, Lazarevic was detained by police on the road from the ethnically divided town of Mitrovica/Mitrovice to nearby Zvecan, where she planned to go to the local health centre to investigate what she said were “multiple complaints” about its readiness to deal with cases of the new coronavirus.

Governments who are already inclined to be repressive seem to believe that old saying, “no news is good news”. By pretending the virus isn’t there, however, it won’t go away. Indeed, keeping a media silence is more likely to feed unhelpful rumours that frighten the population into believing nonsense. Furthermore, leaving it all to officialdom is seldom a recipe for wise choices. Wasn’t it Donald Trump who used his presidency of the United States to recommend that people should swallow bleach to kill the virus? Swallowing bleach kills more than the virus, of course. I suppose it could be said to work in as much as you will certainly suffer no further symptoms of Covid-19 once you’re dead.

The Covid-19 pandemic has, rightly, led to some restrictions being put in place to limit its spread, even if some defiantly foolish people protest and refuse the cooperate. The US recently saw the funeral of a mid-West woman whose vehicle had proudly displayed “no vaccine” and “no mask” stickers.

I don’t suppose her relatives attached them to her hearse, however; she died of the Corona virus in which she did not believe.

I DON’T BELIEVE IN COVID (BUT IT BELIEVES IN ME)

It’s unclear if Hungary’s autocratic far-right president Viktor Orbán believes in the virus or not. He probably does, although he misses no opportunity to criticise the actions of the EU in trying to deal with this unprecedented disaster. Hungary became the first member state to order additional quantities of an anti-Coronavirus vaccine directly, rather than relying on supplies acquired centrally by the EU.

With a population of fewer than ten million, Hungary bought five million doses of the Chinese Sinopharm vaccine and two million of the Russian alternative, Sputnik V. Neither of them had been approved for use by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Furthermore, that’s in addition to the 12-million doses Hungary had already contracted to buy through the EU. That sounds encouraging in a way, at least for Hungarian citizens, but Orbán’s ‘emergency legislation’ blocks public (and media) access to information and criminalises what it calls “fake news”, which basically means any news about the pandemic that he or his government have not approved in advance. Unfortunately, freedom of the press is not enforced as firmly in membership negotiations as other freedoms.

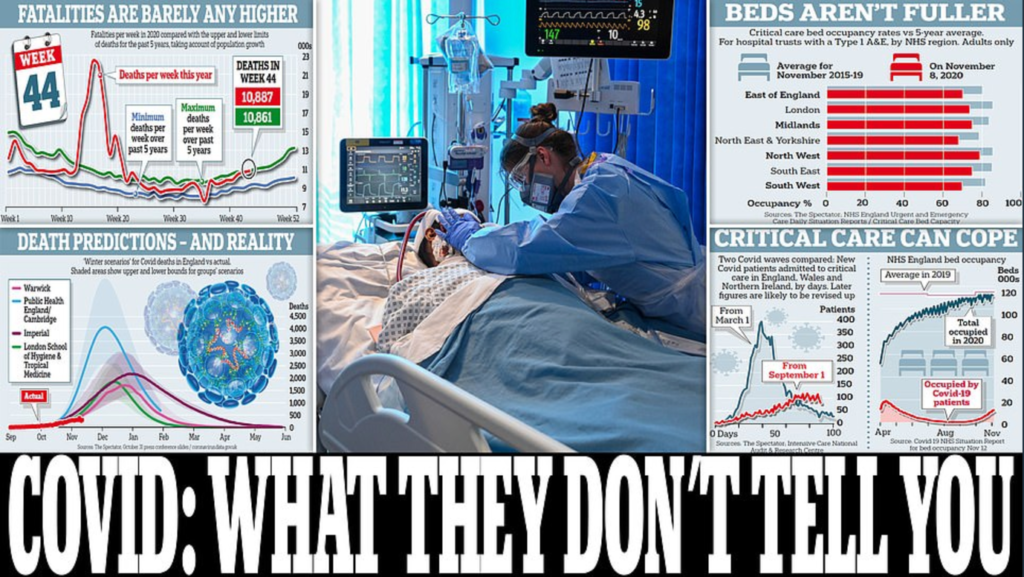

In the UK, it was the government-supporting and consistently right-wing Daily Mail that was initially opposed to Boris Johnson’s measures to rein in the spread of the virus. What happened next was pointed out by the Hacked Off blog and quoted elsewhere. In November 2020, the Daily Mail ran an article under the headline “what they don’t tell you about Covid”. In it, the paper poured scorn on government figures for infection and death rates and suggested that the measures being proposed were an unnecessary infringement on personal freedoms. The article failed to clarify that the figures they were claiming to be “an overstatement” were based on what had been predicted could happen if there were no restrictions at all.

The UK’s Department of Health took the unusual step of criticising the article on Twitter, pointing out that the government’s aim was to prevent illness and to save lives. The Daily Mail swung into action, playing down the Department’s objections, and surprise, surprise, the government backed down without considering how such a step could undermine public confidence in the measures being taken. And yet, the article had, without justification or explanation, dismissed the government’s expert projections as “unreliable”, whilst employing a graphic illustration drawn up by a semi-anonymous blogger with no medical knowledge. What’s more, they suggested that the “only” people dying because of Covid were the elderly, those with pre-existing medical conditions, diabetics and so on. The Daily Mail seemed to be suggesting that their deaths didn’t really count because they were close to death in any case. The “facts” the Daily Mail quoted were not facts, they were extremely selective and misleading and could have led to more deaths. The government made no further complaint about this dangerous and inaccurate article. After all, they have the Daily Mail’s valuable support in other fields (the Daily Mail was an eager cheer-leader for Brexit), which they seemed unwilling to jeopardise, it seems.

There seems little doubt that, unwelcome as it clearly is, the pandemic has given governments that already have some repressive ideas and inclinations a very good excuse to clamp down more firmly. Many have done so. The four ‘shining lights’ of media freedom remain Norway, Finland, Sweden and Denmark. It’s rather depressing to note, then, that four of the worst offenders – China, Cuba, Uzbekistan and Russia – have just been elected to the UN’s Human Rights Council. In terms of press freedom, China comes 177th in World Press Freedom rankings, Cuba is 171st, Uzbekistan 156th, and Russia comes in at an impressive 149th. Interestingly, Europe will be represented by France (34th) and the United Kingdom (35th), despite the latter having chosen the leave the European Union. Incidentally, in the RSF’s ‘league table’ of countries in terms of their attitudes to press freedom, most countries have either stayed where they were or else gone down during the pandemic. Between 2013 and 2020, only Slovenia’s position improved, moving from 35th to 32nd, although it has since dropped back to 36th.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), which constantly monitors the world’s media and its ability to report in an unbiased and fair way, consistently ranks Eastern Europe as the second-worst region for press freedom after the Middle East and North Africa (which count as one region). In the case of the European Union, Hungary and Poland have, unsurprisingly, drawn the most concern. Now RSF says that policies devised to defeat the pandemic – inevitably involving various restrictions designed to halt or at least slow the spread of the virus, further threaten the situation in the region, which has been almost consistently deteriorating over the past decade. It is not a pretty picture. Returning to Hungary for a moment, Orbán was granted sweeping powers by the Hungarian parliament, known as the ‘Country Assembly’ or ‘Országgyűlés’, that criminalise the spread of information that he considers false. Journalists can face large fines and up to 5 years in prison for offending against his judgement, while they also claim that they have been denied access to hospitals and also prevented from talking to health workers, making it almost impossible to report on the issue at all. Concern about the situation has led to a delegation from the European Parliament’s Civil Liberties Committee paying a fact-finding visit in late September 2021. They met with representatives of the government and opposition, and also with journalists, NGOs, and even the Mayor of Budapest. As the visit drew to a close, the delegation leader, French Greens/European Free Alliance member Gwendoline Delbos-Corfield told the media: “The last three days in Budapest have been packed but fruitful.” They met with more than a hundred people with varying views about Hungary and its relations with its own media. “Their diverse accounts will help us to formulate a broadly informed view of what is happening in various aspects: justice, education, media – of the rule of law in Hungary,” said Delbos-Corfield.

ME, ME, ME FIRST!

The Covid-19 pandemic has been the Trojan horse in which repressive (or would-be repressive) governments have slipped new rules into place, just as Greece’s Achaeans put soldiers inside their “gift” to the people of Troy of a large, hollow wooden horse, in order to get into the city after a ten-year siege. And all because Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband, the Spartan King Menelaus. In the minds of the various governments facing the COVID-19 crisis, that effectively gives them control over the media. The Polish government has altered its media market by supporting only pro-government outlets while restricting others. The government and state-owned companies have brought a large number of lawsuits against journalists, with the pandemic causing a considerable increase. In the Czech Republic, journalists are increasingly concerned about the growing concentration of media ownership among a small number of capitalist moguls with close links to the government. Bulgaria, which is the lowest-ranked EU member state on the press freedom index, has brought in prison sentences for any writers of supposedly “fake news” related to Covid (basically stories that disagree with or dispute the official line), while various observers, including EU officials, have complained about increasing government pressure on journalists in Slovenia and also an increasing number of attacks on journalists in Slovakia. Leaders who believe in retaining a tight grip on their country are afraid of the media, which is why they seek so diligently to control it.

The problem is that the loss of media freedom is so widespread. According to the pressure group Freedom House, it has been deteriorating around the world for the last decade. “In some of the most influential democracies in the world,” writes Sarah Repucci, Senior Director for Research and Analysis, “populist leaders have overseen concerted attempts to throttle the independence of the media sector.”

She points out that the threats are all too real but it’s their potential impact on democracy itself that makes them so dangerous. “Experience has shown, however, that press freedom can rebound from even lengthy stints of repression when given the opportunity.” she writes. “The basic desire for democratic liberties, including access to honest and fact-based journalism, can never be extinguished.” Let’s hope so, although a totalitarian government’s most ardent and devoted supporters only seem to want freedom for media that support their own views. The end result is that media freedom has been declining most dramatically in Europe. Repucci points out that: “In some of the most influential democracies in the world, large segments of the population are no longer receiving unbiased news and information. This is not because journalists are being thrown in jail, as might occur in authoritarian settings. Instead, the media have fallen prey to more nuanced efforts to throttle their independence. Common methods include government-backed ownership changes, regulatory and financial pressure, and public denunciations of honest journalists.” At the root of much of the problem is money: powerful influencers have it and will always try to use it to earn themselves and their friends more favourable media coverage.

Freedom House’s ‘Freedom in the World’ report shows that 16 countries have seen media freedom decline over the last five years. Take, for example, Viktor Orbán’s government in Hungary and Aleksandar Vučić’s administration in Serbia.

“Both have had great success in snuffing out critical journalism,” reports Freedom House, “blazing a trail for populist forces elsewhere. Both leaders have consolidated media ownership in the hands of their cronies, ensuring that the outlets with the widest reach support the government and smear its perceived opponents. In Hungary, where the process has advanced much further, nearly 80 percent of the media are owned by government allies. That is a terrifying statistic: one man’s (or in this case two men’s) lust for power and willingness to ignore democracy to secure it has effectively silenced those who disagree with him, however promising and well-intentioned their opponents are. “The problem has arisen in tandem with right-wing populism, which has undermined basic freedoms in many democratic countries,” writes Repucci. “Populist leaders present themselves as the defenders of an aggrieved majority against liberal elites and ethnic minorities, whose loyalties they question, whilst arguing that the interests of the nation—as they define it—should override democratic principles like press freedom, transparency, and open debate.” What they are really saying, of course, is: “I like power and I won’t let anyone take it away from me, however badly and corruptly I run the country, however much I use to line my pockets and whoever has to suffer in order for me to retain that power.” Among Free countries in Freedom House’s “Freedom in the World” report, 19 percent (that’s 16 countries) have endured a reduction in their press freedom ratings over the past five years. This is consistent with a key finding of “Freedom in the World”— that democracies in general are undergoing a decline in political rights and civil liberties. It has become painfully apparent that a free press can never be taken for granted, even when democratic rule has been in place for decades.

WHO WANTS DEMOCRACY?

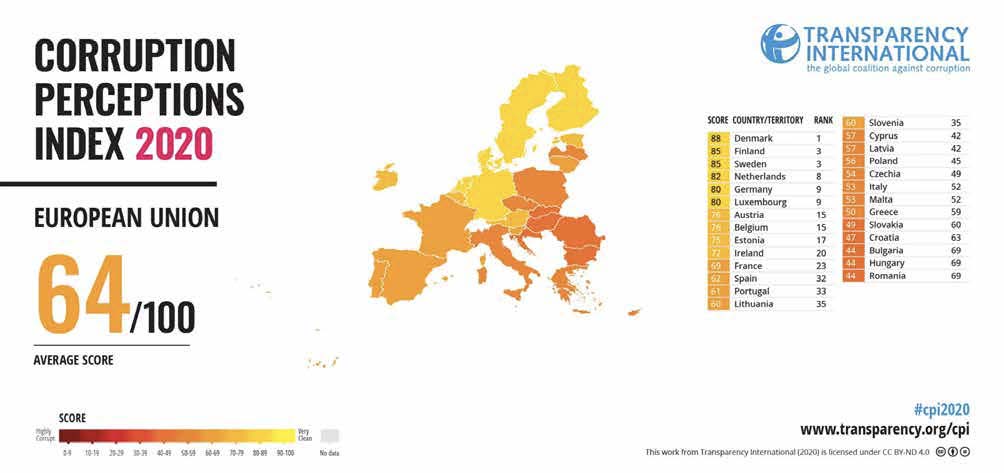

The latest survey from Transparency International makes depressing reading (perhaps depressing for over-ambitious leaders, too). Even within the European Union, normally thought of as fairly squeaky-clean (I emphasise “fairly”) in corruption terms, the latest “Week in Corruption” report says that “some politicians found new opportunities to enrich themselves or to consolidate power – often side-stepping anti-corruption measures”.

The report asks its readers if they wouldn’t rather see political decision-makers putting our shared interests as citizens ahead of their own. “Even if much of this happened behind closed doors,” it says, “EU citizens were aware of resources being skewed in favour of certain powerful groups.” Transparency International took the (surprisingly) unusual step of looking into people’s perceptions of political integrity or “the extent to which EU citizens think decision-makers exercise their power for the common good.” It should make political leaders either sit up and take notice or hang their heads in shame. “We found that people perceive a widespread and systematic lack of political integrity,” says the report, “and that governments across the EU have much to do to free decision-making from undue influence. These findings also bring home the message that building political integrity requires more than fighting public sector corruption.”

The problem is that protecting a country from undue political influence is not easy. “The leader of the far-right Freedom Party of Austria,” reports Freedom House, “until recently part of that country’s ruling coalition, was caught on video attempting to collude with Russians to purchase the largest national newspaper and infuse its coverage with partisan bias.” Is there no end to the degrees of corruption some politicians will pursue in their bids to take the top seat (and make the most money), regardless of its effects on everyone else? Apparently not. Consistency of beliefs is not important, it seems. A few years ago, I covered the visit to Brussels of a Scottish Independence Party politician who was talking about withdrawing from the United Kingdom. British Conservative politicians, along with Labour (Socialist) and Liberal Democrat MEPs, argued fiercely that they would then be outside of the EU and that they would find it hard to get back in, whilst being outside would in itself be economically damaging. Those same Conservatives who later argued for the UK to withdraw in its entirety were, at that time, pointing out the disadvantages for Scotland of not being in the EU. One assumes they believed that and have simply changed their minds, although it’s hard to see exactly why.

In too many countries, the game in political leadership is to buy influence, through whatever corrupt methods are available, even if on closer examination they may appear treasonous. Reductions in the Press Freedom Score have been linked to economic manipulation of media—including cases in which the government directs advertising to friendly outlets or encourages business allies to buy those outlets that are critical in order to silence the criticism.

“They were more common across Europe over the past five years than in other parts of the world,” says Freedom House. “Such tactics of influence and interference are a relatively recent phenomenon on the continent, which has generally displayed strong support for press freedom since the fall of the Berlin Wall 30 years ago.” That was then, this is now, and not all the bullying political bodies are on the other side of a wall. Erich Honecker East German’s communist leader would have understood it very well.

Global press freedom declined to its lowest point in 13 years in 2016, according to Freedom House. There have been unprecedented threats to journalists and media outlets in major democracies as well as new moves by authoritarian states to control the media, including beyond their borders. Only 13 percent of the world’s population enjoys what Freedom House recognises as a truly Free press: “That is, a media environment where coverage of political news is robust, the safety of journalists is guaranteed, state intrusion in media affairs is minimal, and the press is not subject to onerous legal or economic pressures.” Sound like a Utopia? Not so long ago it sounded like Europe. Of course, Europe is very far from being the worst. “The world’s 10 worst-rated countries and territories were Azerbaijan, Crimea, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Iran, North Korea, Syria, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.” Bear that in mind when you book next year’s holidays, especially if you work in the media. I should imagine that we can all forget media freedom in Afghanistan too, sadly. The Afghans are very fine, brave people and deserve better.

DISEASED MEDIA

This article is intended, however, to be about the degree of freedom being allowed to journalists to report on the COVID-19 pandemic. It is a matter of increasing concern to EU institutions. The European Parliament writes on its website that: “This threat to media freedom is often attributed to the recent rise of populist and authoritarian governments, with many world leaders – including leaders of major democracies – increasingly seeming to view free media as an opponent, rather than a fundamental aspect of a free society.” The sad fact is that at the end of this road lies an unfree society we are unlikely to like, where the views of journalists and eventually of all of us are scrutinised to ensure they meet the ‘one-size-fits-all’ opinions of dictatorial governments.

The Covid pandemic makes things worse. “Media freedom proponents have warned that governments across the world could use the coronavirus emergency as a pretext for the implementation of new, draconian restrictions on free expression, as well as to increase press censorship,” warns the European Parliament. “In many countries, the crisis has been exploited for just such reasons, with political leaders using it as a justification for additional restrictions on media freedom.” The press release is concerned that the pandemic has offered an excuse for clamping down on what we can do or say. “Earlier this year, the Association of European Journalists (AEJ) voiced concern over the decline in media freedom that has occurred within the EU in recent years and called on Europe’s political leaders to do more to reverse the trend, in order to protect and reinforce media freedom and uphold the Union’s long-held commitment to a free press.” it says. “Outside the EU, independent media have come under pressure in democracies such as Israel, India and the United States of America in recent years, where journalists critical of the government have been intimidated, threatened and scapegoated by government politicians and their supporters.” Of course, some people view repressive governments as ‘strong’ governments, which they rather like, thus offering a form of support to playground bullies masquerading as politicians. In other words, the pandemic is not only ghastly but is being used as a fig-leaf to cover actions governments don’t want us to notice.

“In some cases,” the Parliament argues, “intense information suppression, narrative control and disinformation campaigns – often carried out in conjunction with highly visible, staged global health assistance – seem to be aimed at covering up government failures and conveying the message that authoritarian nationalism is the most viable answer to the pandemic, as well as that societies must choose between freedom and security.”

The Council of Europe has also expressed deep concern about the erosion of media freedom since the start of the pandemic. It has produced a report that shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists on the continent. “The past weeks have accelerated this trend,” it warns, “with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish ‘fake news’ (news that departs from the official line) even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.” The Council issued a warning to its member states about the worsening situation, to which 60% of member states responded. However, Russia, Turkey and Azerbaijan, three of the worst offenders in terms of media freedom, chose to ignore the reports, as did Bosnia and Herzegovina. Justice seems to have been set aside by governments that believe their own overweening power is more important that their country’s health. “At the end of 2019, the Platform recorded 105 cases of journalists behind bars in the Council of Europe region, including 91 in Turkey alone,” the Council reports. “The situation has not improved in 2020. Despite the acute health threat, Turkey excluded journalists from a mass release of inmates in April 2020, and second-biggest jailer Azerbaijan has made new arrests over critical coverage of the country’s coronavirus response.”

It’s not just the sufferers who are sick, it seems, it is the governance of the offending countries. In a surprisingly wide range of countries, “expanded surveillance measures threatening journalists’ ability to protect their sources,” says the report, “including in France, Poland and Switzerland, as well political attempts to ‘capture’ media through ownership and market manipulation, most conspicuously of all in Hungary. These threats, too, are exacerbated by the actions taken by several governments under the health crisis, which further include arbitrary limitations on independent reporting and on journalists’ access to official information about the pandemic.” It makes for depressing reading.

KILL OR CURE

In Russia and China, restrictions are especially severe. The Kremlin insists that “anyone who spreads false information about COVID-19 risks fines of up to €23,000 or prison terms of up to five years.” “False news” in this case, means anything that contradicts the Kremlin’s own “official” view. Media outlets disseminating information the Kremlin disagrees with could be fined €118,000. “On 22 April 2020, Russia’s Supreme Court specified that the punishments also apply to people who ‘not only use mass media and telecommunication

networks, but also speak at meetings, rallies, distribute leaflets and hang posters’,” the European Parliament statement says. “In Chechnya, President Ramzan Kadyrov issued death threats against Russian journalist Elena Milashina over her reporting about human rights violations in Chechnya under the pretext of combating the pandemic.”

Mystery still surrounds the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and that has helped to muddy the waters around media freedom. It has effectively given governments a free pass to tell whatever lies they want and arrest anyone who disagrees with them. Voice of America (VOA) has catalogued a shocking range of measures used by repressive governments to silence journalists critical of their anti-Covid responses.

WHO / Jin Ni

It points out that in some countries, among them Poland and Hungary, governmental authorities effectively blacklisted any media that criticised them, favouring instead those media outlets seen as ‘sympathetic’. In other cases, such as in Turkey and Russia, the authorities sought instead to monopolize media outlets, putting everything into the care of media companies that could be said to be ‘on their side’. A new report prepared by the Association of European Journalists also highlights such tactics as bogus but expensive lawsuits to discourage dissent.

They’re commonly known as ‘strategic lawsuits against public participation’, or SLAPPs. There has also been a growing trend towards online harassment, especially against female journalists (these brave pro-government spooks prefer to frighten women; it’s safer). “They are increasingly victims of sexist insults and threats. There are cases in Serbia, Spain, in a context of total impunity,” said Ricardo Gutierrez, general secretary for the European Federation of Journalists. “Our report denounces the passivity of online platforms and public authorities in the face of these threats,” he said.

As yet, we do not know what the final outcome will be when – if – the pandemic comes to an end, apart from a long list of fatalities and lasting symptoms. It seems, though, that the body-politic has acquired what, in medical circles, would be called an “auto-immune disease”, parts of the body turning against its other parts, placing the ailment right up there alongside similar medical complaints, such as hives, lupus, graves’ disease and primary biliary cholangitis. The difference is that whereas the medical profession is very often unable to trace how a particular disease started, we know only too well in the case of COVID-19: a suddenly-appearing disease without obvious origin or explanation and a determination by corrupt governments to deny any culpability for the resulting disaster, whilst seeking ever-greater power for themselves. That is not a cure; it is a way of prolonging harmful symptoms for personal gain. Hypocrites would have been horrified.