John Ruskin © Wikipedia

Erasmus Desiderius was the late 14th century scholar, born the illegitimate son of a Rotterdam priest but who went on to study in Paris. He travelled widely around Europe, talking and corresponding with many other scholars and making good use of his travels and his conversations. It was this experience that led him to write “quot homines, tot sententiae”, literally: “there are as many different opinions as there are people”. It is very, very rare to find a lot of people in agreement. Some would say that it’s what makes politics interesting; it’s also what tends to make universal dictatorships time-limited, as populist leaders lose their popularity. Nothing changes in that respect. It was the American industrialist Henry Ford, after all, who wrote: “No two men are just alike. Every new life is a new thing under the sun; there has never been anything like it before, and never will be again.” So, in looking ahead to 2022 I have spoken to a wide range of people with starkly different views on political matters. Oddly, though, on many points, they seem to agree.

2021 was a shocker for many of us. Some of Donald Trump’s supporters stormed the US capital in January and in that same month, COVID-19 deaths worldwide reached two million. Myanmar saw a military coup in February and the imprisonment of state counsellor, Aung San Suu Kyi. The COVID death toll reached three million in April and new US President Joe Biden withdrew US troops from Afghanistan. In July the president of Haiti was assassinated, then before the year’s end Angela Merkel stepped down from being Federal Chancellor of Germany after 16 years. The world changed, as it tends to, but the global pandemic continued and the outlook as 2021 closes is somewhat bleak. I asked a range of people from a variety of backgrounds how they foresaw the year ahead. Some were politicians, holding a wide range of views. Some were political analysts or even leaders of campaigns. Despite some negative signs, no-one was writing off 2022 before it has started, so perhaps neither should we. Here are their views, multifarious but never negative or hopeless. Let’s agree with Erasmus: “Quot homines, tot sententiae”.

PART ONE: “GIVE ME LIBERTY OR GIVE ME DEATH” – ALTHOUGH LIBERTY MAY LEAD TO DEATH

An historian might wonder whatever happened in the 21st century that allowed a disease to spread so widely through a world that could be described as scientifically aware and (largely) medically competent. The SARS-CoV-2 virus has proved just how backward our world is when faced with disaster, rushing to panic and despair rather than considering the possibilities in the light of reason and reacting accordingly. One of the few consoling features is that it hasn’t led to the ghastly pogroms and murderous hysteria that characterised the Black Death of the mid-14th century. Back then, before we’d heard of viruses and bacteria and thus ascribed huge and fatal events to heavenly (or even diabolical) intervention, the chief reaction was hysteria, with people fleeing the cities in a panic, even abandoning their families, and thus helping to spread the contagion ever further, to the furthest reaches of the remotest villages.

Yes, there were doctors and priests who stayed with those who were suffering, although neither achieved much to halt the disease. Too many others, however, refused to look at those seeking help or even to give the last rites to the dead and dying. You could argue that the plague, whichever variety it was that arrived in 1347 (it was probably a mixture), showed up human nature all too cruelly. It claimed an estimated 20-million lives in Europe, possibly more, with Paris losing half its population and great cities like Venice, Hamburg and Bremen losing even more. The plague bacillus may still exist (some scientists believe it has died out), but in any case these days we can use such remedies as streptomycin, tetracycline, and sulfonamides to treat it, rather than having sufferers bathing in urine, rubbing onions or vinegar on the buboes or sitting in excrement, which were among the recommended remedies that (of course) didn’t work.

The massive death toll meant there were fewer people to work the land, so food supplies dwindled and those still fit for work asked more money for their labour because they found themselves in demand. The ruling classes in the UK weren’t having that and passed laws to keep wages down and to prevent labourers from moving to better-paid employment. It didn’t work; even kings and lords, however mean-spirited and cruel, can’t buck the law of supply and demand, so the most positive outcome of the Black Death was a more mobile workforce, earning wages dictated by circumstances and not by the rich tyrant who owned the land. Capitalism emerged, helped by a bacillus. As we can see, the first reaction of those in authority was to preserve that authority; their right to lord it over the poor came before saving lives. There may be little similarity between the bacterium Yersinia pestis, (believed to have been largely responsible for the Black Death), and the virus, SARS-CoV-2, but in terms of human reactions there is a disturbing parallelism.

We have hostile agencies in some countries spreading lies and rumours to cause confusion further and to raise the death toll, we have the largely ill-informed helping to spread the rumours, apparently believing they are in possession of some sort of “secret inside knowledge” denied to others, and we have governments clamping down on media freedom in order to retain control of the flow of information. So, as we look ahead to 2022 the one point upon which virtually all the people I spoke to agree, is that we are looking to a world in which journalism is somewhat constrained and more journalists are likely to be silenced, by jail or by a bullet. “Throughout the West and beyond,” said Gunnar Beck when I asked him if the Covid pandemic had made governments more inclined to forego normal human rights, “governments have become far more overbearing, willing to interfere with civil and individual rights, so yes, we’ve effectively moved from restrained government to overbearing government.” Welcome to the brave new post-pandemic world. Beck is a member of Germany’s right-wing Alternative für Deutschland party, part of the Identity and Democracy Group in the European Parliament. He was the first to mention to me this threat to media freedom but there was a surprising consensus among those I interviewed, from whichever side of the political fence.

Take Seán Kelly, for instance, who, as a member of the Fine Gael party, sits with the largest group in the European Parliament, the centre-right European People’s Party. “Naturally, there has to be less freedom,” he said, “because of the pandemic, because it needs to be controlled, so once governments have explained that to people, the more people have understood it and accepted it.” He added a proviso at this point, which again proved uncontroversial: “Obviously it’s something that couldn’t go on indefinitely and I think if we didn’t find the vaccine we’d be in big trouble because people are so used to their freedom that after a while we have to go back to normality and take our chances.” Let’s hope that applies to journalists, too.

There cannot be very many people today (although I’m sure there are a few) who see the disease, caused by a virus that is only between 50 and 140 billionths of a metre (nanometre or nm) across, as a “judgement from God”, however sinful we all are. One might imagine that such a judgement would be imposed by means of a thunderbolt or a massive meteorite, like the one whose crater was recently discovered under Antarctica and that may have been as much as 50 kilometres across (eight times the size of the ones that did for the dinosaurs), possibly causing the Permian-Triassic extinction some 250-million years ago, long before the first dinosaur even hatched from its egg. It’s thought it could also have caused the breaking up of the massive continent of Gondwana. It wiped out almost all life forms on Earth, though fortunately not quite all; after all, we’re still here. It’s hard to imagine what terrible sins could have been committed by edaphosaurs, gorgonopsias, amynilyspes or trilobites to merit such extreme retribution from an angry deity. Neither, of course, is the virus caused by the use of the new 5G communications standard, despite protests in parts of Eastern Europe demanding a stop to vaccines and the removal of 5G masts, which Europe’s enemies and commercial rivals would love. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), “A large number of studies have been performed over the last two decades to assess whether mobile phones pose a potential health risk.

To date, no adverse health effects have been established as being caused by mobile phone use.” The same goes for those using hand-held devices to send and receive texts, only even more so, because the device is then held further from the user’s head. Needless to say, research continues into possible risks as the use of mobile devices accelerates, but the WHO remains fairly confident: “A number of studies have investigated the effects of radiofrequency fields on brain electrical activity, cognitive function, sleep, heart rate and blood pressure in volunteers. To date, research does not suggest any consistent evidence of adverse health effects from exposure to radiofrequency fields at levels below those that cause tissue heating.” Furthermore, transmissions on a radio frequency cannot, as some allege, ‘create’ a virus. No-one can, whatever method they try, including in a laboratory with rare and expensive chemicals and the help of someone called Igor. Not even Baron Frankenstein could manage that. As the WHO research shows, “Tissue heating is the principal mechanism of interaction between radiofrequency energy and the human body. At the frequencies used by mobile phones, most of the energy is absorbed by the skin and other superficial tissues, resulting in negligible temperature rise in the brain or any other organs of the body.” And I must stress again, it is incapable of creating a virus.

SCIENCE FICTION

But if we cannot manufacture viruses or any other life form in an artificial and scientific way (straightforward biological multiplication not withstanding), neither, it seems, can we totally eradicate them.

“This virus may never leave us, so we have to live with the virus,” I was told by Professor Stefan Schennach, who sits with the Socialists, Democrats and Greens group in the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly (PACE), representing Austria. “We can only protect ourselves and our surroundings with vaccination,” he pointed out. “This virus is not like the Black Death. Some of the sicknesses we have banned from the world, but we cannot ban SARS-Covid.” Well, not yet anyway, which limits our choice of actions. “The race is now on to ensure that we all have booster vaccines that will be effective over a period of time,” Seán Kelly said, “and I think we will expect and demand our freedoms back, which will be essential.” “We can only hope,” said Professor Schennach, “that the people will have the vaccination for 90% plus of the population.” We have to assume, unfortunately, that their number will not include the Covid sceptics, of which there are a surprising number, albeit still a minority, but it’s their choice. It’s one choice they may eventually regret exercising in the way they have, possibly not for long, their period of regret unfortunately curtailed by their premature demise.

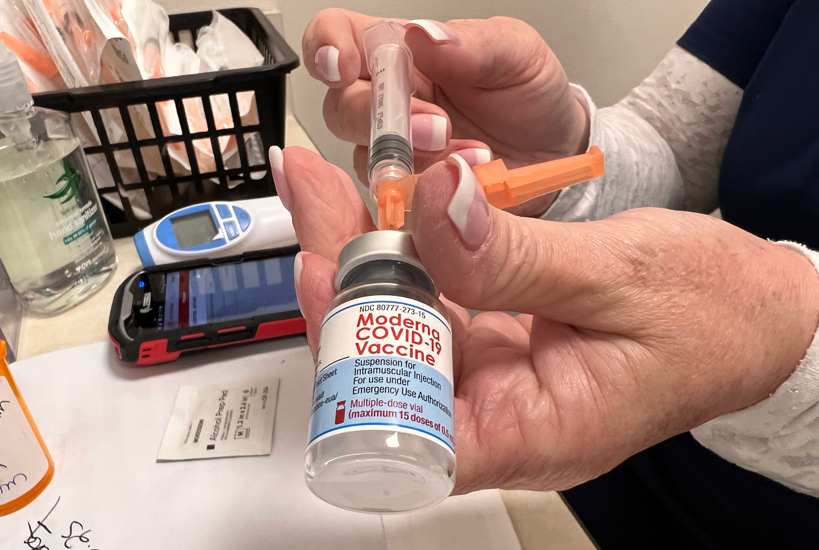

Gunnar Beck, while critical of the EU response to the pandemic (and especially critical of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, for being slow to act, unlike governments in China and the Far East), was quick to praise the British government’s roll-out of vaccines. “I think there’s no question that the UK has managed the vaccine roll-out much better and much faster than the EU,” he said. “There is not the slightest question. The EU has now caught up, but that was after a delay of three or four months, when the UK was well ahead.” Before we all pat ourselves on our collective backs at our triumph over a sub-microscopic quasi-living entity, we need to think carefully. “Now there’s a second question, which is entirely different and separate,” warned Beck, “namely how good these vaccines are. Here the news is distinctly murkier. From what we are learning now, these vaccines are a lot less useful anywhere – not just the UK ones – than first anticipated.” Attitudes to these matters intrigue me, although I cannot pretend to understand the doubters. I have had my jabs – Pfizer for the first two, followed a few months later by a Moderna booster. Unlike the two Pfizer originals, the booster did have side effects which weren’t much fun (like feeling excessively tired and slightly confused) but which certainly beat dying of Covid-19 in my view. As my old mother used to say very late in her life: “growing old is a terrible thing, but it’s better than the alternative.”

It is arguable that vaccines should never be compulsory, although some European authorities are effectively making it so. It was the American statesman Patrick Henry who first used the expression “give me liberty or give me death”, when citizens of the new country were offered the choice between remaining subjects of the British crown or striking out on their own for independence. We all know what happened next; liberty is never the easy choice, although it tends to win out in the end. As a viable alternative, the law could always clamp down on the spreaders of false narratives about the virus, but many of those stories were dreamed up and first disseminated far away, perhaps in some propaganda mill or other rumour factory whose task it is to cause us harm. But for those who pass on what are clearly falsehoods there could, perhaps, be some form of retribution. We are certainly seeing our freedoms eroded as governments seize the opportunity to roll back on them. “We have to be careful,” Schennach warned me, “because civil rights are in danger and whatever we are doing to fight against the pandemic, we should never forget that when we take away civil rights we have to bring those civil rights back and I’m very worried that some countries are not taking so much care for civil rights and human rights and it’s understandable that for a short while if necessary you limit the civil rights but every measure you set up needs an ending so that after the fight against the pandemic, the full civil rights are back in force.” In the interim, there will be scarcely any limit to the numbers dreaming up and disseminating false narratives about the pandemic, invariably coming from that oracle of infallible knowledge so often cited, ‘a man in the pub’. “One has to admit,” Gunnar Beck said, “that the Far Eastern governments have managed things infinitely better, and in fact the restrictions of liberty are no more far-reaching than those we have in effect now. In fact, nowhere are the restrictions worse than they are in Western and Southern Europe. No-one would have thought, two or three years ago, that it would be conceivable that people wouldn’t be allowed to go to work if they don’t get a vaccine. It’s almost tyrannical, it’s turning people into paupers because they don’t want to get vaccinated, it means people are getting vaccinated simply to get their basic rights, the right to work, and not for medical reasons.”

THE PHILOSOPHY OF VACCINATION

We get into interesting philosophical realms here, according to Tiny Kox, a Dutch Socialist politician, if one person’s perception of their rights runs up against someone else’s, whose own rights are threatened by that first person exercising theirs. “Yes, it is an affront against the human rights of the person who wants to go to work,” Kox told me, with regard to the demand that they must be vaccinated first, “but of course there are other people who are working there and who could say – and do say – if someone comes here who is not vaccinated he could harm our fundamental rights, like the right to live.”

Kox cited the 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who pointed out that our freedoms can be limited by the freedoms of others, “for each may seek his happiness in whatever way he sees fit, so long as he does not infringe upon the freedom of others to pursue a similar end,” he wrote. In other words, we can’t limit the freedom of one in favour of the freedom of the other. And if after that you’re still not sure, although “the greatest good to the greatest number” would seem to be a reasonable guide. It’s the basic tenet of utilitarianism, the 18th century philosophy dreamed up by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. It was Bentham who wrote: “The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation.” It sounds a bit outmoded today but in essence, you must admit he had a point.

In today’s world of falsehoods put forward as deep and meaningful truths, the more outrageous the belief being touted, the more credence it seems to gather. Tiny Kox recalled to me how in his youth he would buy newspapers outside church on a Sunday. They were mainly Belgian because the languages of Belgium’s Flemish population and Netherlands Dutch differ mainly in pronunciation – the letter ‘g’ is harsh in Dutch but soft in Flemish – but also in certain words and the positioning of prepositions in a sentence. The Belgians are also less likely to “borrow” convenient words from other languages. These were only minor matters, so the Belgian papers supplied news, otherwise unobtainable on a Sunday, where in the Netherlands the presses were silent on a Sunday, that tended towards the sensationalist, peppered with pictures of young ladies wearing very little. But, of course, sensationalism sells papers (as do scantily clad young ladies): who would buy “man goes for walk in forest” when the alternative version of “man chased by bear in forest” is available? The Belgian papers told Kox and others that “John F. Kennedy did not die, that Elvis was still alive and that man never got to the moon”, but there were other, more truthful articles, and Kox is convinced that most people believed (and still believe) those. At heart, most people prefer the truth. “I think it’s only a very small minority who believe it’s 5G, or the Russians, or aliens that have something to do with Covid,” he assured me. He told me that the previous day a neighbour had asked his opinion about a letter she’d received, in which it was alleged that in the American state of Vermont, more people had died as a result of having received the vaccine than from Covid.

“So I asked her if it was her idea,” he told me. “‘No,’ she said, ‘it was in a letter from a friend’. I asked her if she or the friend were virologists or epidemiologists and she said ‘no’. I asked her if she knew where the state of Vermont was on a map of the United States and she admitted she’d never heard of it.” And so on and so forth; that’s how rumours start and spread. I know there are some anti-vaxxers out there who believe the vaccine will merge with your DNA, and one rapper claimed that the vaccine had made him infertile, while an extreme few believe the vaccine delivers a chip into your bloodstream that allows Bill Gates to track you, though it doesn’t explain why he might want to. There is an old saying, quoted by the late fantasy writer Terry Pratchett in his book ‘The Truth’, and now, almost word-for-word, by Tiny Kox as well: “a lie can run around the world before the truth has tied its shoelaces”.

Of course, the lie has to be salacious if it’s to succeed and the ease with which it will subsequently circulate is something upon which our less reputable governments rely. Sadly, there is no shortage of them. ‘Fake news’, as it’s called, has become a fact of modern life and it’s widely used by disreputable administrations, of which there is sadly no shortage. “’What is truth?’ asked jesting Pilate, and did not stay for an answer,” wrote Archbishop Richard Whately of Dublin (who was by training a political economist), thus effectively copping out of having to analyse Pilate’s supposed words.

Religious people doubt that Pilate said it at all as he was never known to jest. Indeed, he was not a nice man and was ordered back to Rome to face trial for cruelty and oppression after complaints about him from the Samaritans. If even the ancient Romans thought he was too cruel, he must have been truly unpleasant.

In the debates (and protests) over restrictions there has been much talk about so-called “2G”, and it’s not a reference to the mobile phone standard replaced by 3G and then by the current 4G standard. It stands for “geimpft oder genesen”, German words meaning vaccinated and recovered. Those that cannot claim 2G status are increasingly likely to find themselves excluded from certain shops (the ones generally described as ‘non-essential’) and also from social events and venues. Angela Merkel, now ‘Acting Chancellor’, is very worried about the rising hospitalisation rate. “We know we could be better off,” she told DW, “if the vaccination gap wasn’t so big.” In Germany the 2G rule will be imposed in any of Germany’s sixteen states in which more than three people per 100,000 have been hospitalised. The outgoing Merkel government has come in for a great deal of criticism for failing to bring down the hospitalisation rate, although it’s not certain that the new government, a coalition of the Social Democrats (SPD), the Green Party, and the neoliberal Free Democrats (FDP) will have greater success. The virus clearly doesn’t read the newspapers or obey political rules.

An SPD member of the Bundestag, Karl Lauterbach, has accused Merkel’s outgoing administration of being too slow to act to hold Covid infection rates within bounds. He told the administration that they had “underestimated” the fourth wave. “Some scientists were not really giving an alert, others were,” he told DW. “There was a lot of wishful thinking in our government.” Meanwhile, in some states the health system is being simply overwhelmed. Germany’s doctors are demanding clear rules to “break the chains of infection.” “The virus is still with us and threatens the health of citizens,” said Olaf Scholz, the Federal Vice-Chancellor. He stressed that efforts must be intensified to convince Germans who are not yet vaccinated to become fully vaccinated and also to encourage those already vaccinated to have the booster shot. He told the lower house that everything must be done to “ensure that millions of citizens get a booster; that is the task of the next weeks and months.” According to the German health ministry, around 67.3% of Germans are now fully vaccinated (or were by 12 November).

DANGER AROUND EVERY CORNER

Of course, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 is not the only threat to the peaceful progress of Europe into 2022 and beyond. There is also political instability and the risk of armed conflict here and there. The matter became a subject of debate at the European Parliament’s “hybrid” session in November. By “hybrid”, I mean that although some MEPs were present in person, as well as some guest speakers, others only joined in on line. With European Council President Charles Michel and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in attendance, a number of political group leaders said that not enough was being done to address various attacks on the rule of law, something upon which the entire European Union is based.

Opinions varied but among other problems to be highlighted, Ska Keller, a German Green MEP, called for far great vaccination roll-out, including outside the EU, while Marco Zanni, an Italian MEP from the Identity and Democracy group, said that the violent protests that have been taking place in a number of cities are proof that the EU institutions should be doing more. There were calls for more solidarity with Poland, Latvia and Lithuania over the threat from Belarus to swamp the border areas with ever larger groups of migrants, mainly from Iraq. All have asked for EU help with the crisis. There were calls for more action against the Belarus dictator, Alexander Lukashenko, with an EU-wide migration policy, according to Martin Schirdewan of The Left in Germany, in order to prevent what he described as “an evil autocrat from instrumentalising refugees.”

A bit late for that, I’d say. Commission President von der Leyen announced that transport operators involved in Lukashenko’s blackmailing-by-trafficking operation face being blacklisted, but warned that any counter-measures must respect the rule of law and fundamental rights. Footage emerging from the border area suggests there’s been relatively little of that on show. For the refugees that nobody seems to want there appears to have been very little sign of humanity.

Listening to the debate is an unedifying experience and it makes the future look even bleaker. Everyone wants action of some sort, if only they could agree exactly what. “I think the crucial question,” Brendan Donnelly, the director of the Federal Trust, told me, “Is whether the European Union can ‘tame’ (and I’m not quite sure what that taming would mean, whether it would be legal, political, the imposition of sanctions or whatever) the Polish and Hungarian governments, and particularly the way they have been floating, constitutionally, the idea that they are no longer bound by European legislation. That really is cherry-picking, and that is what the British government was trying to do. I can understand the caution of the other countries of the EU, but unless they take a firm stand, perhaps by financial sanctions, within the context of the European Union, to show that there’s a price to be attached to the behaviour of the Polish and Hungarian governments, I think the basis of trust and of credibility, upon which the whole of the European Union rests, may be undermined.” Reinhardt Butikofer, a German Green member of the European Parliament, told me that among the ordinary citizens of Poland there is majority support for EU membership, so Warsaw looks unlikely to follow London down the twisting, ever-narrowing path into obscurity and relative irrelevance. And while Poland wants to stay in for something like ideological reasons, Hungary is more dependent on the EU financially. It couldn’t easily afford to withdraw.

It would be easy to dismiss Belarus as an aberration, too far gone down the road to tyranny to turn back. That would be wrong, according to Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, leader of democratic forces there. Speaking to the European Parliament, she urged MEPs to amplify the voices of the ordinary Belarusian people. She reminded the House of the many voices of democracy in her country that had been silenced by Lukashenko’s thuggery before turning to the migrant crisis on the border, and she posed a question: “Supposing this abuse of migrants is somehow stopped,” she asked, “do you really assume the regime’s abuses and threats beyond its borders will end there?” She warned that there would be more to come: the smuggling of drugs and contraband, military provocations and even nuclear disasters by Europe’s borders. Tsikhanouskaya told MEPs that the democratic movement in her country cannot afford to wait for Europe; expressions of solidarity and concern are all very well but they need to be turned into real concrete action. Europe, she warned, needs to become more proactive when facing up to autocracy. She urged members to call for sanctions. “Let me assure you,” she said, “sanctions do work. Continue holding a consistent sanctions policy. Sanctions split elites, destroy corruption schemes and divide people around Lukashenko.” She said she wanted to see Europe standing in a more united way with Belarusian democratic forces. “Let’s not forget the Belarusian prisoners of conscience,” she urged, “and let’s help those who were forced to leave the country. Today, not only democracy in Belarus but also democracy in Europe depend on whether we will walk this path together.”

Will Europe have the courage of its convictions, being only too well aware that Lukashenko’s closest ally is Vladimir Putin. Nobody wants to provoke Putin, but perhaps a little provocation wouldn’t go amiss. Putin may like to show off his arsenal of weapons and how easily he can spread space debris across the path of the space station as it wheels through the already over-crowded void. All-out war against NATO, though, may not be part of his game plan. Brendan Donnelly, Director of Britain’s Federal Trust, doesn’t believe that to be the case. “I don’t think that Russia is in any traditional sense an expansionistic power at the moment,” he assured me. “I may be wrong about that, but that’s my sense of it. They’re always trying to push at the envelope, other than having any long-term strategy, such as to re-occupy those parts of continental Europe that they’ve lost.” A reassuring point of view and based on much study. It would seem, then, if we’re to be optimistic, that Putin’s forces will not be sitting around your Christmas table this year. But that doesn’t mean he’s not thinking about it; he’s certainly nobody’s Santa Claus. Europe, as we know, faces a great many problems and we have by no means exhausted them. We can be assured that 2022 won’t necessarily be a bed of roses, but neither should it be a wasteland of thorns and briars, we can hope. Wear your walking boots but tread softly.