John Ruskin © Wikipedia

It was the 19th century English art critic, painter, social commentator, and all-round polymath John Ruskin who wrote that “Government and cooperation are in all things the laws of life; anarchy and competition the laws of death.” He was a firm believer in reform long before such views were fashionable, including education for the labouring classes and for women (not a fashionable idea at the time), and he warned about the environmental damage being done by the Industrial Revolution.

Since he believed in governments cooperating, one must assume he would have approved of the European Union, as well as the United Nations, ASEAN and the Council of Europe, among other examples of international cooperation. If he were to regard the problems on Europe’s doorstep as we move towards a new and equally troubled year, he would presumably have recommended that the various governments get together in common cause and ‘sort it out’.

What we need to do, according to Cristiana Grigore, who campaigns for her Roma people, is to “connect and communicate beyond great divides”. Being Roma, she is painfully aware of the divisions in our society and believes that the current situation is not sustainable. “We live in so many bubbles,” she told me, “that are defined by our wealth, or ethnicity, or privilege or lack of privilege, or need to protest or need to protect, or rights, and there is less and less communication and real genuine connection between parties, in a way that we can listen to one another, empathise with one another, understand the common struggle and understand who can be supportive, and why this matters beyond the immediate cause we want to protect.” I first met Cristiana in the garden of her parents’ house in Romania, not far from Craiova.

With the family being Roma, it was a small place and fairly remote. She went on to win a Fulbright scholarship to Vanderbilt University, gaining her degree in International Education Policy and Management in December 2012. She now runs the Roma People’s Project at Columbia University in New York, seeking to dispel negative impressions about the Roma and Sinti people and other minorities and bring them out of the shadows and into the light. The same could be said to apply to Europe as a whole.

“Europe is not happening and it’s all in our hands,” Professor Danuta Hübner told me. Professor Hübner spent five years as Commissioner for Regional Policy but gave it up in 2009 to stand for the European Parliament as a member of Poland’s Civic Platform party, sitting with the centre-right European People’s Party. “You know all this famous European decision-making through political will, and my feeling is that there is a lot of political will to find solutions and move forward on many fronts, actually, because of the way we reacted to the pandemic nearly two years ago.” Hübner takes comfort from the way in which Europe’s initially disjointed response became more organised once Europe got over its panic. “It was clearly as an emergency and without the right competences, but we managed to move. You saw the flexibilities; you remember the taboos?

They were gone all of a sudden, so I think that we proved that in difficult times we have the machinery to move, but then (and it was surprising really to me) we established very quickly the system for the longer term, for the recovery, for new ways of financing it, the new way of approaching economic governance, the co-ordination, so I think a lot has been done to create a chance for Europe to survive.” The actual success of EU authorities also impressed Professor Schennach, an Austrian Parliamentarian who sits with the Socialists, Democrats and Greens group in the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly (PACE). “You should not forget that for health measures, they have no mandate.”

Throughout Europe, however promising the political signs, there are those who take different lessons from the pandemic and our response to it. As a result, they have been engaging in protests, especially in the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany but elsewhere, too. What they’re objecting to are the restrictions put in place in a bid to halt the spread of COVID-19. Their excuse is that they don’t really believe the virus exists, despite a death toll that had reached 5,227,930 globally by the end of November. “I take the view that people are actually protesting about the wrong things,” said Sajjad Karim, a former British Conservative Member of the European Parliament. He no longer has much time for the party under its current leadership, nor for people who jump on populist bandwagons to demonstrate their dissent.

“The things that they ought to be protesting about they are just accepting, and the things that are common sense and good for all of us, they’re up in arms about. Obviously, with the rise of the anti-vaxxers, and people protesting against the Covid pass and all those sorts of things, I take a very different view to all of that; actually, it’s a matter of civic duty to make sure you get vaccinated. If ever there was a situation in which ‘we are all in it together’, this is it.” In other words, he believes there can be no sensible argument against us protecting ourselves, our friends and colleagues, and those we meet, by way of having a vaccination. “To protect my parents,” Karim said, “my children need to be vaccinated; otherwise it doesn’t work.”

SNEAKING UNDER THE VIRUS RADAR

But while he believes that the need for vaccination is beyond dispute, that doesn’t mean there is nothing to protest about. Karim says there certainly is, we just don’t recognise it even when we’re told about it, assuming we get told about it at all. There appear to be acts of government in preparation using the pandemic as cover. “On Friday (19 November) it came to light that the British government is pushing through a new ‘nationality’ bill,” he informed me, “with amendments that would allow it to withdraw the nationality of British citizens (even those that were born here of immigrants) without giving them notice, yet nobody was protesting against this.” It’s probably because few in the UK have heard about it; I certainly hadn’t until Karim told me. And it is now marching towards the statute book without anyone raising much opposition. “It’s gone through first reading, it’s gone through second reading,” he had to tell me, since I had heard nothing about it, nor had it been mentioned in the media I had seen, “It only came out to the public on Friday night. Even the opposition has accepted it.” And where are the concomitant protest marches, angry words, and petitions? Well, nowhere, it seems. We’re back to bubbles again, and bubbles spell trouble.

“I think the crucial question,” Brendan Donnelly told me, “Is whether the European Union can ‘tame’ – and I’m not quite sure what that ‘taming’ would mean, whether it would be legal, political, through sanctions or whatever – the Polish and Hungarian governments, and particularly the way that they’ve been ‘flirting’ constitutionally with the idea that they are no longer bound by European legislation.”

Donnelly, Director of the London-based Federal Trust for Education and Research, sees problems ahead for Britain’s relations with the EU, its greatest trading partner, following the UK’s withdrawal. Some have said that the only good thing to emerge from “Brexit” from the EU’s point of view is that the way it has damaged Britain will not encourage others to try the same thing. It’s very unlikely that Poland in particular, I was assured, would opt for “Polexit” because research suggests that 90% of Polish voters would choose to stay in the Union. It’s a dilemma and a matter of grave concern for pro-Europeans like Professor Hübner. “We have to be very clear that within the ruling coalition in Poland we have practising politicians who are openly against Europe, openly against European values, openly against the ethics of Europe, which means links with the judicial system of the European Union, with the fact that all our judges in Poland are also European judges, and dismantling the judicial system on the basis of the unconstitutional nature of the European treaties, which has happened and it’s extremely serious.”

It all looks very worrying but despite that, most of the people I spoke to remained quite positive about the prospects for 2022. The thing is that in this uncertain world there are many more things to worry about than attempts by nationalists to undermine the EU. Like China, for instance. “Well certainly China represents a very fundamental alternative to what we stand for,” said Reinhard Bütikofer, a German Green MEP who is a member of the China delegation. “China represents the most extreme kind of authoritarianism; some people call it ‘tech totalitarianism’. China represents a different kind of global order. They’re not into multilateralism; they’re not into international rule of law. They are aiming for a return to power politics, where the powerful act as they will and the less powerful act as they must.”

Bütikofer’s view was given a big boost from an unexpected quarter: the head of MI6, Britain’s secret intelligence agency. The senior spies of most countries seldom go public and they don’t come much more senior than the man referred to as ‘C” (in Ian Fleming’s James Bond books and in the movies he’s called ‘M’), whose real name used to stay secret. Richard Moore, as he is called, gave a speech at London’s International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), in which he warned about the dangers lurking behind the smiles of Xi Jinping and, for that matter, Vladimir Putin.

He told his audience that his service saw four major threats to security: Russia, China, Iran and international terrorist groups that recognise no borders. “Chinese intelligence officers,” he warned, “seek to exploit the open nature of our society, including through the use of social media platforms to facilitate their operations. We are concerned by the Chinese government’s attempt to distort public discourse and political decision making across the globe.” Given the long experience of MI6 internationally, are the personal ambitions of Xi Jinping something over which we should lose sleep? Well, yes, says Moore, pointing out the damage already done.

“The Chinese Communist Party brook no dissent,” he told his audience. “Beijing have eroded Hong Kong’s ‘one country, two systems’ framework, and removed individual rights and freedoms, in the name of national security. Its surveillance state,” he warned, “has targeted the Uighur population in Xinjiang, carrying out widespread human rights abuses, including the arbitrary detention of an estimated one million Muslims.” The US meanwhile, is trying to demonstrate the superiority of democracy, but it’s a divided country with a large number of violent religious extremists, which is not very convincing. So here we have a large nation, somewhat set in its ways and internally divided facing an emergent China with global ambitions. Some have likened it to the situation in the 5th century BC, when the Athens-led Delian League faced the Peloponnesian League, led by Sparta: two powerful trading nations, each fearing the other’s growth and success.

The Greek historian Thucydides wrote in his History of the Peloponnesian War that such a set of circumstances would inevitably lead to armed conflict. It’s called the ‘Thucydides trap’, and some American political writers fear history may be about to repeat itself. According to Thucydides, the two empires debated their differences at Sparta, with the Athenians present defending their Delian League and Athens’ reputation, but also to make veiled threats.

“Our aim is to show you what sort of city you will have to fight against, if you make the wrong decision,” said one delegate, according to Thucydides in the first chapter of his History of the Peloponnesian War.

“It has always been a rule that the weak should be subject to the strong; and besides, we consider that we are worthy of our power.” The words seem to have a very strong resonance for today’s world.

MY PIROZHKI IS OFF

China is not the only problematic country, run by an extremely autocratic leader, of course. We have only to look at Russia, whose increasing self-confidence led to its agents murdering those who were seen as Putin’s enemies. For instance, Anna Politkovskaya was shot dead in the elevator of her Moscow apartment block for reporting on the Chechnya war in a way that displeased Putin.

The press conference room at the European Parliament in Brussels is named in her honour. Former KGB operative Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned with polonium in London. It had been given to him by agents Andrey Lugovoy and Dmitriy Kovtun of the FSB (successor to the KGB). He died of radiation poisoning. Sergei Yushenkov, one of the leaders of the Liberal Russia party, became the second politician from that party to be murdered in Moscow. Less than a year earlier, Vladimir Golovlyov, a co-chairman, was shot and killed in the capital. That was in August 2002.

In 2018, in the pretty and historic English city of Salisbury, Sergei and Yulia Skripal were poisoned, although they survived, fortunately, after a long recovery. Skripal is a former Russian military officer who also served as a double agent for the British intelligence, so he was never likely to be popular in the Kremlin. He and his daughter were poisoned with a Novichok nerve agent hidden in a spray perfume bottle which put both of them in hospital, critically ill. The poison was then carelessly thrown away by the would-be killers, despite its deadly content, and while a police officer attending the initial attack ended up in intensive care for some time, having also suffered from radiation poisoning, in a nearby village a local woman, Dawn Sturgess, found the discarded bottle, tried what she thought was perfume and died very soon afterwards. Annoying Putin comes at a high price, it seems.

It’s all very strange, because whenever my work has taken me to Russia I have found the people there warm, friendly, and keen to engage with others who’ve had different life experiences. (Pirozhki, by the way, is a popular Russian street food: small baked or fried puff pastry parcels, normally filled with potatoes, meat, cabbage, or cheese. They are delicious). There’s not much about Vladimir Putin that most people would describe as delicious. Destructive, perhaps, or depressing, or even detrimental to the public good. But does any country have the will (or the ability) to rein him in? His activities and seeming lack of self-restraint have influenced the drama taking place on Poland’s border with Belarus, as the Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko weaponizes some of the world’s neediest people to cause problems for the European Union. He is angry about the sanctions the EU imposed for his fraudulent election victory and for his use of fighter jets to force a Ryanair flight from Greece to divert to Minsk, where dissident journalist Roman Protasevich was snatched after agents boarded the plane and placed him under arrest.

Some have described it, reasonably, as ‘state hijacking’. Protasevich remains in custody. His crime? Having been the editor of the Nexta channel, which was run from outside Belarus and was opposed to Lukashenko and his administration.

Lukashenko has encouraged refugees from the Middle East to believe they can get into the EU easily if they reach his country first. It was never true; he just wanted to see thousands of poor refugees having to be held back by force from entering Poland, Latvia or Lithuania, which would make for embarrassing television coverage for the EU. He doesn’t seem to think it matters if they live or die; he was sure Putin would support his inhumane actions. In a recent speech on the Russian state news agency, MIA Rossiya Segodnya, Lukashenko emphasized Belarus’s close ties with Russia: “Our Fatherland is one: from Brest to Vladivostok. Here we have two states – Belarus and Russia. Two states, one Fatherland,” he said. But in threatening to cut off gas supplies being piped through his land to European customers, he may have overstepped the mark.

Lukashenko said in an interview with the Satellite News Agency that “the integration of Russia and Belarus has no boundaries”, but it seems he was wrong.

He had annoyed Putin, with whom he claims to be “in constant touch”, however hard that is to imagine. “Migration is an issue that we didn’t manage to find solutions to,” Professor Hübner told me. “Solutions exist to terminate migration, but not solutions to cope with it or manage it, because there will be people coming to Europe in the decades to come and we know also that there will be other issues to migration.” It’s a depressing thought, a little like the SARS-COV-2 virus: we never planned for it because we didn’t understand how big it would be and so we didn’t see it coming. She believes we will see other reasons driving attempts to migrate to Europe, such as climate change. “We have never found a European solution,” she told me, “that would allow us to cope with migration and that would take into account the global tendency in Belarus, the demographic tendencies in Europe, the fact that we are ageing.”

FAIRER FARMING, GREENER WORLD?

Hübner notes that most of the migrants are relatively young, but rather than taking the opportunity to find people to undertake work in currently unfilled positions, there are populist politicians keen to use fear in a population to elevate their own positions by offering short-term fixes and stoking up nationalism. There seemed no easy way out, but Hübner told me that eventually Angela Merkel rang Putin, who told her “’You have to talk to Lukashenko.’ That’s how it happened, although we’ll probably never know the details.”

Putin in peace-making mode may surprise us, although it doesn’t surprise British Conservative member of parliament Neil Parish. He is less concerned about the risk of falling into a ‘Thucydides’ trap’, partly because the West isn’t keen on rushing into war but also because neither are Russia or China in his view. “I mean, Russia would not win an all-out war, but there would be a lot of bloodshed, so therefore I do think we should make sure we’ve got the missiles in Poland, we have to make sure we’ve got enough to protect Europe, because war comes about when we are weak, not when we are strong.” I should point out that Parrish is no war-monger; he’s a farmer and prefers peace for his livestock. He foresees a good future for the agro-economy, as long as we learn lessons from the past. “I think we’ll see greener agriculture,” he said. “I think we’ll see less fertilizers, less fungicides, being used. In this country we’re looking at geno-technology to see if that can help us produce food with less chemicals, and I think we will see generally more organic matter going into the soil; better management, less soil erosion, but we’ll have to be careful that we don’t destroy our production so that we then import from deforested rain forests illegally in the Amazon or from Malaysia, and I think Europe and Britain have to be careful as we go forward, maintain good levels of production in a greener way, reduce our carbon output, reduce our methane gas, which we can slightly by altering the diet for the sheep and the cattle, so I’m optimistic that we can still maintain a reasonable level of production, but we do have to be careful. A bit like the overall green agenda, let’s not do away with all the wild production to save some gases, just so that everyone can get on their aeroplanes and fly away on their holidays.”

Such behaviour seemed all too visible as the COP26 meeting ended. It wouldn’t be possible if Ziya Altunyaldiz had his way. His report before the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) won unanimous support. He is a member of Turkey’s socially conservative Justice and Development (AK) party and rapporteur for a report to the Strasbourg assembly that addresses issues of criminal and civil liability in the context of climate change. The report makes it clear that “member states of the Council of Europe have recognised their legal responsibility for climate change at national, European and international levels and thus, indirectly, the concept of ‘climate justice’.” The report demands that the various governments should “ensure that relevant legal instruments are available to respond to environmental and other harm caused by climate change; in this context, access to judicial (civil, criminal and administrative) remedies, both to prevent and to compensate for damages caused by climate change in relation to actions or omissions by the state, natural and/or legal persons, is essential.” Altunyaldiz believes that wealthy countries should back up their promises with cash. “They promised before US$100-billion,” he reminded me, “but as far I know, they have just delivered around 20% of it up to now, and the rest of it, unfortunately, is still to pay.” He seemed to doubt it would be.

Altunyaldiz wants very much to see environmental measures taken to make this a greener world, but he believes – reasonably enough, one might argue – that if the rich want a cleaner world they must help the poor to pay for their part of it. “If you want to change something you must be genuine and serious and also take things responsibly and try at least to help to pay for whatever you have done to the climate.” Altunyaldiz wants to see net zero emissions by 2026 and believes it to be possible, if the will is there to achieve it. He wants to see environmental crime recognised right across all the Council of Europe member states and beyond their borders, and to regulate and legislate and put it in force. He also, in his report, makes it clear that whoever pollutes the environment has to pay for it. He supports the notion that “the polluter pays”, which may not find many supporters among some of the world’s biggest industrial concerns. “The people should have the right to litigation,” he told me. “That is why I think that litigation is important. All around the world, NGOs and individuals and companies are now taking issues to the courts. Litigation is increasing and I think it’s going to be effective.” There’s nothing like the risk of being dragged through the courts and possibly being fined if found guilty to make would-be polluters toe the line.

WAYS OUT OF THE MAZE?

That, however, came in that report by Altunyaldiz and not from the much-heralded COP26 conference in Glasgow. We shouldn’t despair altogether, says Inka Hopsu, a member of the Green League in the Parliament of Finland, in commenting on the outcome of the international get-together. “It has its good side,” she assured me, “in that multilateral work is still possible. We are committed to the Paris agreement and the countries come together and have their discussions, but at the same time the results of the meeting are not that strong.” Perhaps it would have achieved more if another of Hopsu’s ambitions had been fulfilled. She wants to see the rôle of young people in conflict prevention and conflict resolution enhanced. She fears that we get so many stale old solutions being put forward because it’s the same stale old politicians doing it. In her report to PACE, she points out that the proportion of younger people within legislatures has actually gone down, highlighting the rather shocking fact that only 3.9% of Europe’s national parliamentarians are under 30 years old.

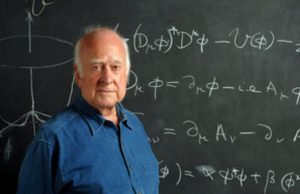

Do the old hands fear the youngsters wouldn’t be any good at it? The evidence suggests otherwise: people like Newton, Einstein, Dirac, Heisenberg, Bohr and Pauli did their best work when they were in their twenties. Peter Higgs proposed the existence of the sub-atomic particle that bears his name when he was in his mid-30s. He is now 92 and physicists are still working with and looking further into the Higgs Boson, which takes his name and is what gives all matter mass.

Higgs admitted to me when I interviewed him in 2013 that he now gives the more difficult mathematical calculations involved in his ongoing research to younger colleagues because he finds them a bit difficult, which doesn’t make him any less of a genius to my mind. But many young people are reluctant to get involved in politics, which can be a slow and frustrating process. In Hopsu’s report, she says: “The Assembly deeply regrets that nearly six years after the adoption of the first UN Security Council landmark resolution concerning youth, peace and security, little progress has been made, and young peacebuilders find that their space for action is diminishing rather than growing.” Only Finland has introduced an action plan for implementing UNSC resolution 2250, as it’s known.

The report also notes that UNSC Resolution 1325, which is about women, peace and security has taken more than two decades even to reach a few national agendas, going on to point out that: “The Assembly is particularly concerned about the exclusion of young women from peace processes and insists that their inclusion in all stages of conflict regulation should be the focus of immediate attention.” There is an old saying: “God moves in a mysterious way”. Politicians move in ways that are not only mysterious but also very often occult, arcane and unfathomable, and done (if done at all) at less than snail’s pace. Hopsu, though, hasn’t given up hope. “Some of the youth movements, the environmental youth movements are very strong,” she assured me, “and they are now on the streets, and they are definitely showing that they are interested.”

Of course, people who get involved in politics at a young age often change their minds, moving from left to right or right to left or in some bizarre sideways direction. Take Thomas Piketty, for instance, Director of Studies at the École des hautes études en science sociales and a professor at the Paris School of Economics. He now professes a kind of socialist realism, but he started his political journey further to the right. “Like many, I was more liberal than socialist in the 1990s, as proud as a peacock of my judicious observations, and suspicious of my elders and all those who were nostalgic,” he writes in his latest book, ‘Time for Socialism’. “I could not stand those who obstinately refused to see that the market economy and private property were part of the solution.”

There are, of course, no ‘quick fixes’ in politics or in sociology and certainly not in economics, either. Those who are still committed to their teenage beliefs when they’ve grown to adulthood should be viewed with deep suspicion. People will normally respond to changing circumstances, even (perhaps especially) when it involves espousing a different set of political beliefs. For us today, the question is: in which direction will they go? As long as it’s away from anarchy and towards cooperation and consensus, everything should be well, at least if John Ruskin can be believed. Perhaps, though, we should note the comments of the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1830, before we get too enthusiastic: “In politics, what begins in fear usually ends in folly.” 2022 should be an interesting year.