Inmates in a US Prison © Riverside County Sheriff’s Office

It’s a simple fact of life: when a government anywhere in the world decides something is a crime, its biggest, most forceful response is usually to send someone to prison. Taking away a person’s freedom is meant to punish them and scare others from doing the same thing. But here’s what’s fascinating – the entire world can’t agree on how to actually use this power. What gets you locked up in one country might only get you a fine or community service somewhere else. And even when two countries both choose prison, the sentence in one might last a few months, while in the other, it could stretch for decades. So the exact same action, tried in two different courtrooms on opposite sides of the planet, can lead to two completely different futures. In the end, the kind of justice you get seems to depend less on what you did – and more on where you were when you did it.

If you take a step back and look at how the US and Europe handle justice, you’re not just seeing small policy tweaks – you’re looking at two very different worlds. The sheer harshness of sentencing in America compared to Europe isn’t some accident. It comes from deep-rooted beliefs about crime, punishment, and what society should be. These are two clashing philosophies. In the US, the justice system and the legal process are intensely adversarial, and for decades, politicians have built careers on being “tough on crime.” The driving idea here is to punish and make people pay for what they’ve done.

Europe, on the other hand, tends to put more faith in the state to actually reform people, not just lock them away. The goal isn’t just to punish, but to eventually reintegrate. This isn’t just some theoretical debate. It makes us ask a very basic, but vital, question: What do we actually want our justice system to do? What kind of society are we trying to build with the power we give our courts?

| Punishment, Politics, Prisons

When we talk about how punitive a country’s justice system is, the measuring standard is almost always the imprisonment rate – the number of people locked up per 100,000. And that number tells you something, for sure, but it’s also somewhat imprecise. It really neglects the huge differences in how countries actually use prison. Some nations send hundreds and thousands of people to prison, while others are much more selective.

Then there’s sentence length: in some places, getting more than a year is rare; in others, it’s totally standard. And as for pre-trial detention or remand as it’s known in the UK, this is extremely common in some jurisdictions, but not so much in others.

The crazy part is that because of all this, two countries can have nearly identical imprisonment rates but be punishing people in completely different ways. In Europe, take the Netherlands and Germany, for example. The Dutch system might imprison more people overall, but often for shorter stints. Meanwhile, Germany imprisons far fewer people, but when they do, the sentences tend to be longer. It’s the same overall number, but a totally different philosophy.

In the United States, it’s a different story. It’s become something of a global trend over the last few decades for prison sentences to get longer, but even against this backdrop, the United States stands out as a real outlier. When you look at both the average length of sentence handed down and the actual time people end up serving behind bars, the US figures are consistently higher than those in most other nations. This really underscores a broader pattern in corrections that sets the US apart.

Now, it’s true that the US has to deal with higher homicide rates than many European countries, which might partly explain why long sentences are used more often there. But that fact alone doesn’t really explain why the average prison term for serious crimes like homicide and sexual offences is also so much longer. The distinction becomes even more striking when you compare the US to parts of the world with substantially higher rates of violence. For instance, many Latin American and Caribbean nations have higher homicide rates, yet US states often end up incarcerating more people and for longer periods.

Perhaps most telling are the figures for life sentences. The United States accounts for 40% of all people serving life sentences worldwide. Even more striking, it accounts for the vast majority, 83%, of those sentenced to Life Without Parole (LWOP). Some state laws mandate minimum confinement periods that are exponentially harsher than anything you’d find in Europe.

Then there is what is known as the “Three-strikes” law. This is in reference to baseball, where the umpire calls strikes when a player is batting. The first strike is when you are convicted of a first serious crime (armed robbery or murder). You go to prison for a normal sentence. The second strike is when you are convicted of another serious crime. This time, the sentence will be much longer than usual. The third strike is when you are convicted of any crime (even a less serious one, like shoplifting or burglary). This is your “third strike.” Instead of a short sentence for that minor crime, you are automatically sent to prison for a very, very long time – often 25 years to life.

This unique reliance on long-term incarceration is deeply entrenched in the American system, and it originates from its highly decentralised political and criminal justice structures. The problem is further exacerbated by a number of individual states that have exceptionally large populations of people serving these very long terms, maintaining the country’s position as a global anomaly.

| Deterrence vs Rehabilitation

A detailed account of the disparities in sentencing severity between the United States and European nations, naturally, requires an examination of fundamental philosophical differences, legal structures, and socio-political contexts. But the core of the disparity can be summarised as a contrast between a generally retributive and deterrence-based model in the US and a rehabilitative and reintegrative model in Europe.

In the United States, the justice system often speaks the language of retribution. The driving idea is that if you commit a crime, you must be punished in a way that precisely matches the harm you’ve done – an eye for an eye, or ‘just deserts’. There’s also a powerful element of deterrence: the belief that by making the consequences harsh and highly visible, you’ll scare others away from following the same path. Above all, there’s a deep-seated urge to simply remove the problem – locking people away to make society feel safer, if only for a while.

| Specific Sentencing Practices

The vast majority of countries around the world – that’s 183 out of 216 – have laws that allow for life sentences. On top of that, at least 64 countries have what’s called a “de facto” life sentence. This is when someone is given a prison term so long, like 35 years minimum before any chance of parole, that it essentially means life behind bars. In fact, 15 countries use this kind of sentence instead of a formal “life in prison” law.

Globally, the number of people serving life sentences has grown a lot. Back in 2000, there were about 261,000 lifers worldwide. By 2014, that number had jumped to nearly 479,000, and the numbers keep growing. A few of the countries that have contributed the most to this increase are the United States, India, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and Turkey. (Source: Council on Criminal Justice CCJ https://counciloncj.foleon.com)

Perhaps the most fundamental distinction between the American and European justice systems is the sheer length of time people are locked away. The gap isn’t just one of scale, but a difference in kind.

This is most apparent with life sentences, which are handed down much more often in the US. But the real divide becomes clear with sentences like Life Without Parole (LWOP). This means exactly what it says: you will die in prison. A European court issuing such a sentence is almost unthinkable.

Perhaps even more symbolic are the multi-century sentences handed down by some courts. A term of, say, 200 years isn’t a measurable period of rehabilitation or punishment – it’s a formal and absolute declaration. It serves as a legal mechanism to ensure that imprisonment extends far beyond a single natural lifetime, closing the door on the very idea of a second chance.

In Europe, while life sentences exist, they are governed by a principle of humanity: the belief that people can change. A life sentence almost always comes with the possibility of a parole review, typically after serving 12 to 20 years. This isn’t about being soft on crime; it’s about offering a real incentive for rehabilitation and acknowledging that a person at 60, for example, is not the same person they were at 25.

You can really see this different way of thinking in action in places like Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Their whole approach is built on a simple but powerful idea: taking away someone’s freedom doesn’t mean you have to take away their dignity. Prisons there are designed to feel as normal as possible. Instead of just punishing people, they focus on teaching them new skills, offering therapy, and getting them ready for a life outside. The sentences themselves are much shorter, and a 20-year term is almost unheard of – it’s saved for the very worst cases. In fact, the European Court of Human Rights has ruled that all life sentences must be “reviewable” and “reducible.”

You can trace this deep split in thinking back to history and culture. After the unimaginable horrors of the Second World War, European countries had seen firsthand what happens when a state is allowed to punish its citizens cruelly and without limits. That experience left them with a deep distrust of pure revenge as justice. Instead, they built new legal systems with human rights at the very core – like the rule that absolutely forbids “inhuman or degrading treatment.” This is why you won’t find the death penalty anywhere in Europe; it’s completely outlawed.

The American story is different. Its culture was heavily shaped by a frontier spirit of individualism and self-reliance. In that view, crime is often seen as a personal moral failing. The response, then, isn’t to ask how society might have failed the person, but to demand that the person who failed must be punished severely.

But there is a troubling trend that needs to be considered: over the past few decades, the US hasn’t just been sending more people to prison – it’s been keeping them there for much longer. Take 2019, for example. Well over half of everyone in prison – 56%, to be exact – was serving a long sentence. That’s a significant jump from just 46% back in 2005. Now, what’s interesting is that this shift wasn’t necessarily because courts were handing out more long sentences. It was actually because they were giving out fewer short ones. So the overall pie of people in prison started to have a much bigger slice of long-termers.

And for those serving a decade or more, the time they actually spent behind bars grew substantially. If you look at people released after a long sentence in 2019, they had served an average of 15 and a half years. That’s a staggering 60% increase from 2005, when the average was just under a decade. (Source: Council on Criminal Justice https://counciloncj.com)

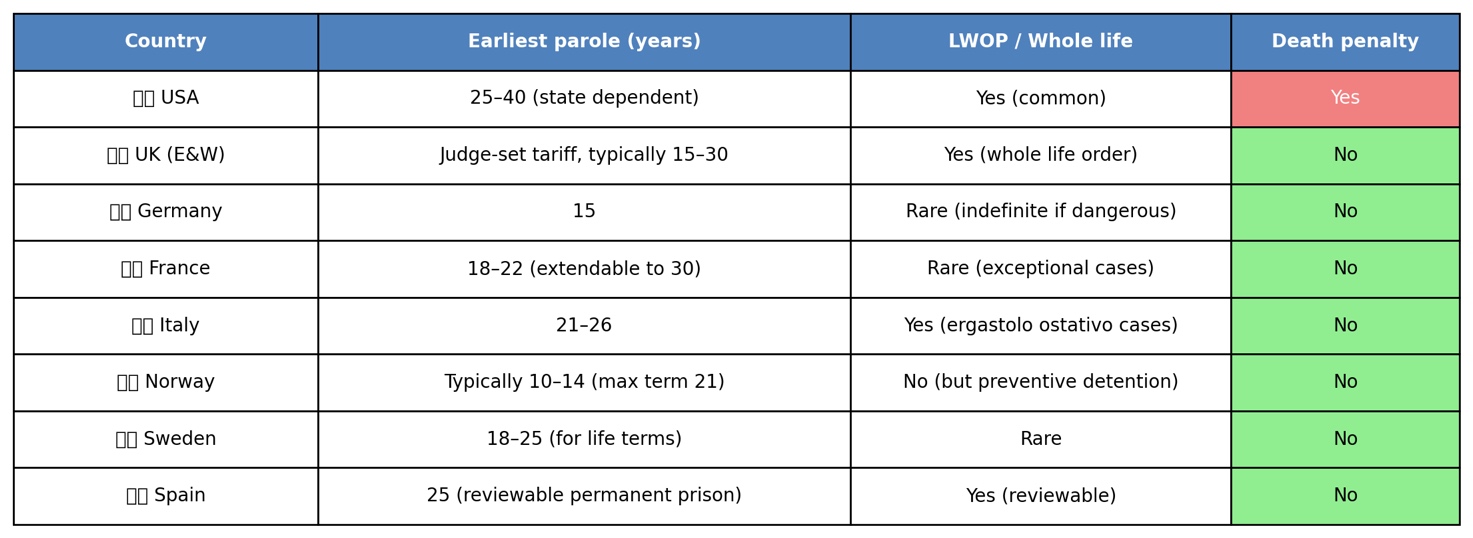

This chart represents an overview of sentencing for murder in the United States and selected European countries. The figures include parole timing, whole life/life without patole (LWOP) availability and death penalty status.

With regard to Italy, ergastolo ostativo (literally “obstructive life sentence”) is a particularly severe form of life imprisonment that is reserved exclusively for the most serious crimes such as Mafia type association, involving multiple murders, terrorism resulting in murder and particularly heinous and premeditated, multiple murders. The goal isn’t just punishment but permanent incapacitation of individuals deemed extremely dangerous to society. It is Italy’s closest equivalent to a “whole life” or “life without parole” (LWOP).

| Sexual Assault Convictions

Comparing sexual assault conviction regimes between the United States and Europe reveals significant differences in legal definitions, investigative processes, and sentencing outcomes. In the US, the legal system uses a narrow, precise definition, often distinguishing between degrees of rape and sexual assault based on specific criteria (use of force, penetration, victim’s capacity to consent). Definitions can vary significantly from state to state. In Europe, many countries have adopted much broader, consent-based definitions following the Istanbul Convention. For example, laws in Sweden, Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands define rape as any sexual act without explicit and voluntary consent. This shifts the focus from the perpetrator’s use of force to the victim’s lack of agreement.

In the US, sentences can be exceptionally lengthy, especially under “Three-strikes” laws or in cases with aggravating factors. The use of the death penalty for certain aggravated rape cases (in a few states) is a uniquely American practice.

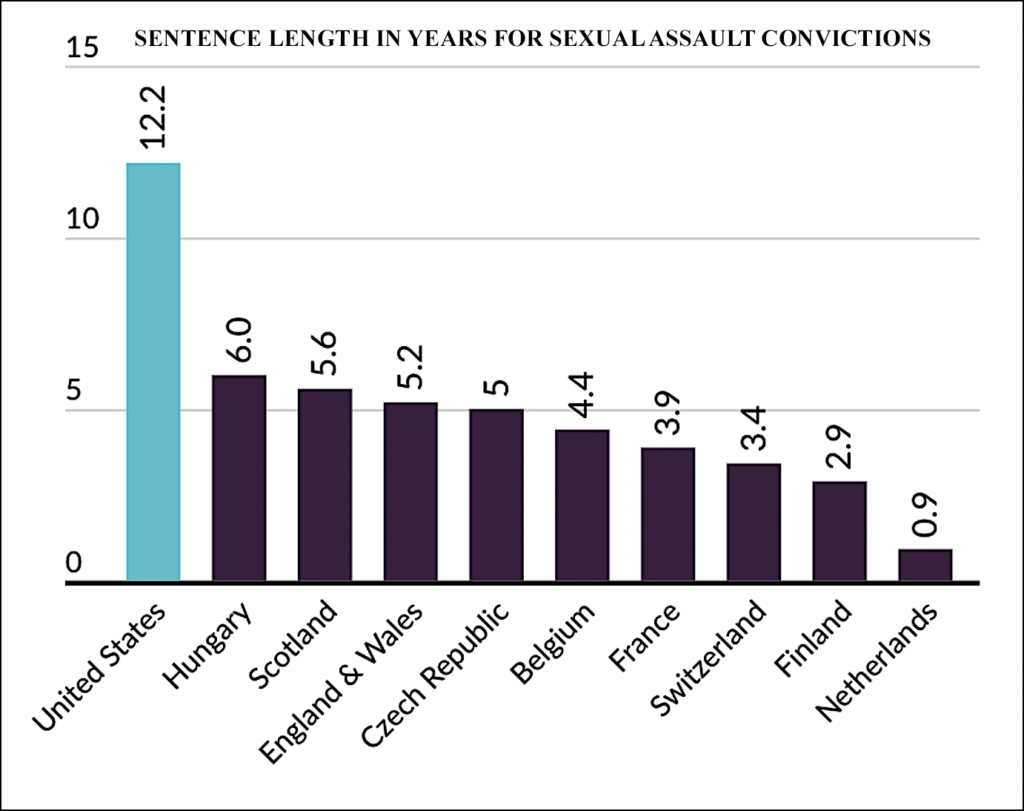

This comparative chart shows the average sentence length in years for sexual assault convictions in the United States and selected Europen nations (Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics www.bjs.ojp.gov)

But here’s the thing – this trend toward locking people up for longer isn’t just happening in the US. It’s quietly become a global story. Take Belgium, for instance. In less than ten years, the number of people there getting sentenced to a decade or more shot way up. And it’s not alone – places like England, Wales, and Germany have all seen noticeable jumps in longer prison terms. Even countries like France and Lithuania are part of this slow but steady creep toward tougher sentencing. It seems that over the past few decades, much of the world has been shifting, almost without notice, toward keeping people in prison for longer. What started as an American phenomenon has, in many ways, gone global. (Source: K. Drenkhahn, M. Dudeck & F. Dünkel (Eds.), Long-Term Imprisonment and Human Rights).

| Drug Offences and Violent Crime

When it comes to drug offences, the difference is just as dramatic. Over in the US, their “war on drugs” led to mass imprisonment, with strict laws meaning even small-time possession or dealing could land someone in prison for decades. It’s an approach that’s all about punishment.

Here in Europe, however, the mindset is completely different. Drug abuse is generally seen as a public health problem. While the laws do vary from country to country, the focus is much more on treatment, reducing harm, and community sentences. Following Portugal’s lead, plenty of countries have decriminalised having small amounts of drugs for personal use. So, if it’s your first offence and you’re caught with a bit of cannabis or something similar, a long stretch in prison is really unlikely. You’d far more likely get a fine, probation, or be directed towards a treatment programme.

And this pattern holds for violent crimes as well – things like murder, rape, and robbery. The US has a clear preference for handing out much longer sentences. A murder conviction there can easily mean 35 years to life behind bars. In many parts of Europe, the maximum sentence might be more like 15 or 20 years, and you could be eligible for parole even earlier. The goal isn’t so much about getting decades of revenge; it’s about a sentence that fits the crime, but which still leaves open the possibility of someone eventually being reintegrated into society.

This chart shows the average sentence lengths in years, for homicide convictions in the United States, a number of Latin American countries with relatively high numbers, and selected European nations. (Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics www.bjs.ojp.gov)

U.S. data on average sentence length were collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). These figures were based on individuals’ first releases from state prisons in 44 states after serving time for any given offense; these states accounted for 97% of all individuals released from state prisons nationally.

Basically, these numbers show that the average prison sentence in the US has more in common with countries in Latin America than it does with other wealthy nations in Europe. You could argue that America’s higher murder rate – compared to Europe – is part of the reason for its tougher sentences. But that doesn’t really explain why the sentences for murder and sexual assault are so much longer across the board. What’s even more telling is the comparison with Latin America. The US actually has a lower murder rate than most Latin American countries, yet it locks people up for this crime for far longer. In most of Latin America, someone convicted of murder will likely serve less than twenty years.

| The Death Penalty and the Ultimate Question

The difference in how the United States and Europe view the death penalty is a major one, going far beyond just a legal issue. It’s really a clash of core beliefs about justice, the government’s role, and human rights.

In the United States, the death penalty is still very much a part of the legal system, with 27 states and the federal government having recourse to it. While it’s not always used, the debate around it is fierce as supporters argue that it provides justice for victims, acts as a deterrent, and offers closure for grieving families. However, the system is deeply flawed. It’s often criticised for disproportionately affecting minorities, leading to wrongful convictions, and having very long and costly legal processes. Ultimately, its continued use in the US, supported by many politicians, reflect a public belief that for some crimes, this is the only acceptable punishment.

Europe has taken a completely different path by abolishing the death penalty across the continent. This isn’t just a choice; it’s a mandatory condition for any country that wants to join the European Union. This unified stance came from a deliberate reflection on Europe’s history of violence, especially the horrors of the 20th century. After experiencing two devastating wars and witnessing the atrocities committed by totalitarian regimes, and the use of the death penalty as a tool of state oppression, European nations had a profound change of heart. They came to believe that a state killing its own citizens to prove that killing is wrong is a contradiction. This core belief was formalised in the European Convention on Human Rights, which explicitly calls the death penalty “inhuman and degrading treatment.”

For Europe, abolishing the death penalty was a crucial part of building a new identity based on human rights and the protection of the individual. It was a clear way to distinguish themselves from their own violent past and to draw a moral line between the new democratic Europe and the oppressive regimes they were leaving behind. For countries from the former Eastern Bloc, getting rid of the death penalty was a key step in showing their commitment to these new European values and distancing themselves from their oppressive histories.

Be that as it may, the death penalty isn’t the cause of longer US sentences; it’s a symptom of a justice philosophy that prioritises punishment above all else, in sharp opposition to Europe’s focus on human rights and rehabilitation.

To put it simply, the radical difference in sentencing between the United States and Europe is more than just a legal matter – it’s a fundamental difference in outlook. On one side, you have a system focused on punishment and exclusion; on the other, a system that aims to correct and reintegrate.

This contrast ultimately raises a deep question: what is society’s responsibility towards those who break its laws? The answer, as seen in the practices of these two powers, shapes not just the future of the offender, but the very character of a nation.

While the American reliance on long prison terms has shown its limitations, the European outlook is more nuanced. It dares to propose a hopeful, if demanding, idea: that people can redeem themselves. This system’s ambition is not merely to punish, but to restore. It operates on the belief that a justice system’s true power lies in its ability to rehabilitate – to prove that even after a wrong, a right is still possible.