Featured image copyright: © Edm

OK, I confess: I’m a Luddite. In case you’re unfamiliar with the term, it refers to someone opposed to machines taking away jobs that had been traditionally done by hand, undermining and undervaluing the skills of time-served craftspeople. I don’t mean that I want to go back to the bad old days of horse-drawn taxis, coal fires and candlelight, but I’m concerned about the unrestrained spread of new technology. Some of it, of course, is invaluable to today’s connected world and extremely useful. Some of it is rather less so. I was never keen on the idea of the Internet of Things (IoT), despite a long TV interview I conducted a few years ago with one of its chief advocates, Jeremy Rifkin, the American economic and social theorist and writer of several books on the subject. Streetlights that come on only when a vehicle or pedestrian is approaching? Washing machines that can be turned on remotely from your mobile phone?

No, thanks. What’s wrong with turning a knob? Why on Earth would anyone want to switch a washing machine on remotely unless another robot of some sort was able to gather up the clothes to put in it and add the washing powder, not to mention unloading it afterwards? I don’t mean that I want to see the back of washing machines altogether, of course. I can still remember my mother, grandmother and aunt all working together at the big washtub in the kitchen, complete with scrubbing boards (later adopted by skiffle groups as musical instruments), a heavy mangle and bars of hard soap and then having to use buckets to empty the tub. I was only a small boy at the time but I could see it was hard work.

The original Luddites were a group of 19th century English textile workers, sworn to support one another by oath, who deliberately smashed up mechanised textile mills. The wool and cotton industries were vital parts of the English economy, and mechanised mills were becoming essential, so the owners were naturally a bit upset. The machines threatened the jobs of hand weavers, however; Charles Mason of Mason and Dixon fame was a Gloucestershire man who had seen and was distressed by the effects of mechanisation in the textile industry and the harsh repression of protestors. The Luddites were supposedly named after Ned Ludd, allegedly a weaver from Anstey, near Leicester in the English Midlands, who, it’s claimed, smashed two weaving frames either for revenge after being whipped for idleness or after being taunted by local youths. He may not even have existed, however. Whether he did or not, there is a street named after him in his supposed home town. Experts say the Luddites were not against all kinds of machinery, only the kind that was used in what they called “a fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labour practices. Furthermore, they wanted to ensure that the machines were operated by skilled workers who had served apprenticeships and who were paid proper wages.

In many ways the Luddites had it easy. The machines were large, hard to hide and, however complicated and inventive, they carried out relatively simple and easy-to-understand tasks. Now we have the Internet and the capacity it offers to do all sorts of things. The tech giants have promised in the past to clean up their acts, but their owners, investors and managers have seemed unable to see past their balance sheets. We are left with the merry free-for-all that provides advantages for all, but which also poses dangers for the honest and law-abiding while offering endless opportunities to the criminally inclined and for those spreading malicious and dangerous propaganda. Without the Internet would the anti-vax movement even exist? An American woman who became infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus apologised to her on-line followers for her temporary disappearance from her usual site and blamed the pandemic, only to be inundated with posts calling her a liar, a stooge and worse for claiming that COVID-19 exists when so many conspiracy theorists insist that it doesn’t. At the risk of upsetting them further, it does; just ask the relatives of those it has killed. Conspiracy theories, indeed, thrive in the nasty nonsense-land of the Internet, alongside paedophilia and “revenge porn”. It seems to have opened the way for the truly wicked to behave in horrible ways, safe in the knowledge that IP addresses are not easy to trace and law enforcement agencies generally don’t have the technical resources nor the money to pursue wrongdoers.

A ROBOT VACCUUM CLEANER FOR THE AUGEAN STABLE?

The European Commission, long a supporter of the Internet of Things, now seems to be growing increasingly alarmed about the Internet of the ‘things-we’d-rather-weren’t-there’. There is no doubt that the IoT itself offers a number of potential advantages in striving towards a more eco-friendly and less polluting future.

Jeremy Rifkin talked to me about what he called the “collaborative commons”. “What’s happening,” he told me, “is that capitalism is giving birth to a new economic system, its progeny, and this is the sharing economy of the collaborative commons.” He predicted that capitalism, undergoing its first major evolution since the early 19th century, will be totally transformed by 2050. He insisted that people will start to make use of objects only for as long as they need them but without actually ever owning them outright, while systems will talk to each other with no need for us humans to get involved. “We have to begin to create common regulation standards for inter-operability across the EU so we can create an integrated technological platform for the integrated single market,” he said. EU member states find it hard to agree to common standards on most things, but when they do, they tend to stick to them, a fact the British government’s Brexit-obsessed ministers failed to grasp, apparently believing they could divide them.

Rifkin believes the days of the private car are coming to an end and the Internet of Things will help that to happen. “Young people don’t seem to want to own automobiles anymore,” he assured me. I’m not sure I see much convincing evidence of that just yet, but he’s clearly done his research and undoubtedly knows much more than I do. “Automobile ownership is grandma and grandpa. The whole millennial generation want access to mobility, not car ownership. They want car sharing. They’re moving from ownership to access.” OK, so he’s looking into a future thirty years from now, in which a mobile phone can bring a shared vehicle to your door. Probably. Of course, it can only function with an Internet of Things, but will the better-off kids settle for the same kind of shared or borrowed vehicle as the less wealthy? I think the problem here is that it fails to take account of pride and the urge to show off. Even if Rifkin sees the looming end of car ownership, I don’t see the looming end of snobbery; far from it. I hope Rifkin is right, for the sake of the planet, but there will have to be some pretty drastic housekeeping for the technology thus employed before it fulfils all its promises.

The problem is that we in the West already depend too dangerously much on digital technology and all those satellites out there that it requires in order to function. With Russia and China (neither of which is as dependent on the technology) developing and testing anti-satellite weapons there is a real risk of severe disruption. What’s more, there is always the possibility of a big solar Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) such as the famous Carrington event of 1859, which blacked out large parts of North America and caused the telegraph system to fail. If something similar happened today we’d be left with no navigational aids, radio or Internet communication, no weather forecasts and possibly no electricity. Large areas of the planet could be plunged back into the stone age in the blink of an eye. And yet the big tech companies stand accused of abusing their dominant positions.

Cleaning up these Augean stables of the big tech companies won’t be easy, used as the technology is by political extremists, hostile foreign powers, trolls, hate merchants, racists, sexists, supporters of gender violence, purveyors of sex and pornography, paedophiles, those with inflexible religious views and so on. Even Hercules might have considered the task too difficult; the stench from a mountain of stinking animal droppings would be the sweetest perfume by comparison with some of that all-too-human filth. The big tech companies have known about it for years but have brushed off responsibility, claiming they are merely providing a shop window and not its content, for which they cannot be held responsible. The European Commission has had enough of lame excuses and have introduced the Digital Services Act (DSA). Its aims are covered in the text of the proposal: “The resolution on ‘Digital Services Act: adapting commercial and civil law rules for commercial entities operating online’ calls for more fairness, transparency and accountability for digital services’ content moderation processes, ensuring that fundamental rights are respected, and guaranteeing independent recourse to judicial redress. The resolution also includes the request for a detailed ‘notice-and-action’ mechanism addressing illegal content, comprehensive rules about online advertising, including targeted advertising, and enabling the development and use of smart contracts.” Coincidentally (or perhaps not) the UK government published its own new regulations for tech companies, rather oddly working as what has been called an “ex-ante” set of rules, telling companies how they should conduct themselves, rather than calling for penalties for them if they fail to do so. In the UK, it will be in force by April 2021, according to the government, and in charge of making firms comply will be the Digital Markets Unit, overseen by the Competition and Markets Authority.

THE TOOL TO DO THE JOB

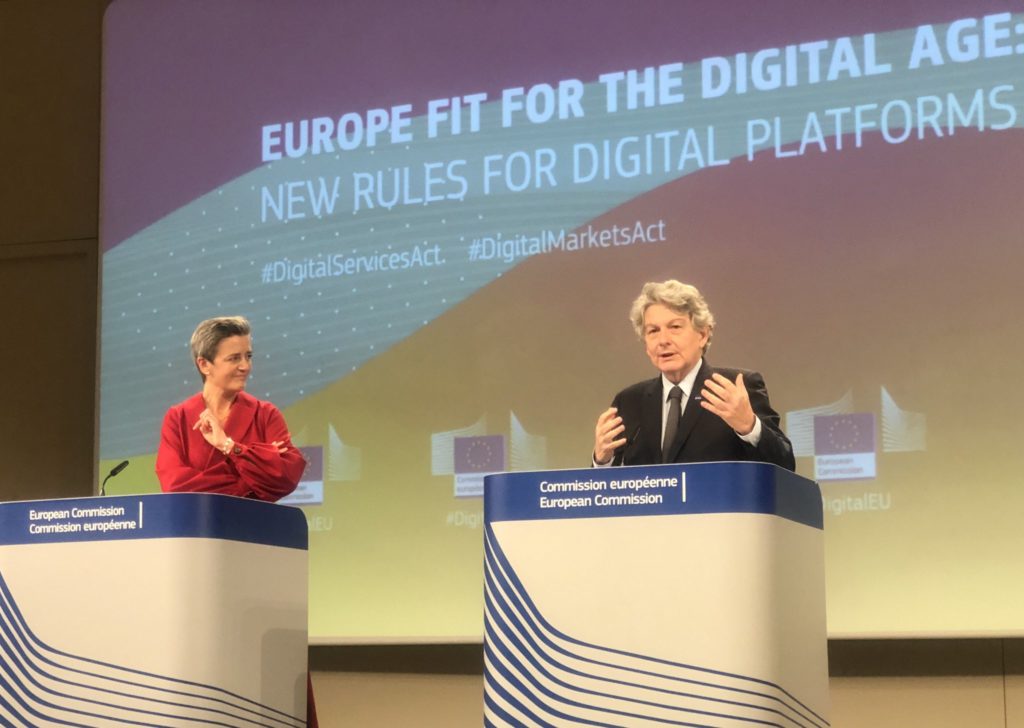

The EU’s DSA is a wide-ranging tool to tackle a variety of perceived issues, including ensuring that content is safe and harmless, as Commissioner Margarethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President for a Europe fit for the Digital Age, explained.

“Digital platforms will be required to swiftly remove illegal content,” she told a press conference at the European Commission, “but in parallel to explain to the user why the content was removed and give him or her a chance to complain about it. Also, the new obligations to know your customer will require online marketplaces to check their sellers’ identity before they are allowed to use the platform, which will make it so much difficult for dodgy traders to do business.” She also told the media that the tech giants will have to come clear on why a search puts a particular product, service or piece of information higher than others in terms of relevance and importance. Any favouritism must be for a reason that demands explanation. “So the Digital Services Act will also require platforms to tell us how their algorithms work. How their recommender systems select the content that they show us, but not require platforms to reveal their algorithms. It will give us a better idea of who is trying to influence us and how, choice as to whether we want to trust this or not.”

In addition to the DSA, the Commission has proposed the Digital Markets Act (DMA), which serves a slightly different purpose, aimed more at bad practice among operators than at directly helping consumers. Firstly, it considers the way in which big tech, through acting as a ‘gatekeeper to services’, is able to garner information about preferences from the way consumers behave with their competitors. It’s a goldmine of data that can be turned to advantage. Unfair advantage, in the eyes of the Commission. “With the Digital Markets Act,” Vestager explained, “gatekeepers shall no longer use the data they collect from all the businesses that they host when competing against them. They will have to create data silos that allow for separation of the data generated in their different business lines.” The DMA will also prevent tech companies from effectively shutting out their competitors through unfair payment systems to which they alone have access. “For instance, let’s say a gatekeeper develops a new payment solution. It works with a piece of software or hardware that is only available to its own payment solution. To address this issue, we have introduced a new interoperability obligation.

Anytime a platform offers such a service, it needs to make sure that competing providers are not shut out from the platform.” Furthermore, ‘gatekeepers’ will not be allowed to gain advantage by artificially ranking their chosen product above the equivalent products of their rivals. “To end this practice, the Digital Markets Act will oblige the gatekeeper to adjust its search algorithm to make sure rival offers receive the same level of prominence as its own offers.” It goes without saying that these changes will not be welcomed by some of the big tech companies. Failure to comply, however, could lead to fines of up to 6% of a company’s annual revenue, which in the case of Facebook, for instance, would come to $4.2-billion (€3.44-billion).

The Commission clearly doesn’t trust the tech giants. Under the new rules, the companies will be obliged to reveal to regulators how their algorithms work, with the threat of fines of up to 1% of annual revenue if platforms supply incorrect, incomplete or misleading information to the regulators, or if they refuse to permit an on-site inspection. Misleading advertisements – so-called ‘dark ads’ – were widely used on social media platforms during the UK’s Brexit referendum campaign and in recent US elections without explaining who was funding them or where the information they contained came from.

Under the DSA they will be obliged to retain libraries of past advertisements and provide users with information about who supplied the ads, who paid for them and why particular users were targeted. The Commission says it consulted a wide range of stakeholders before unveiling this legislative package, including the private sector, users of digital services, civil society organisations, national authorities, academia, the technical community, international organisations and the general public.

Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton told the media: “Many online platforms have come to play a central role in the lives of our citizens and businesses, and even our society and democracy at large. With today’s proposals, we are organising our digital space for the next decades. With harmonised rules, ex ante obligations, better oversight, speedy enforcement, and deterrent sanctions, we will ensure that anyone offering and using digital services in Europe benefits from security, trust, innovation and business opportunities.”

Quoted on the 20 iapp website, Shopify Associate General Counsel and Data Protection Officer Vivek Narayanadas said: “The DSA is, I think, one of the most important proposals being discussed at the Commission right now. It’s an incredibly promising opportunity to address a range of really difficult and important issues to make sure the Internet remains a safe place for users and a competitive space for businesses.”

Shopify, incidentally, is a multinational e-commerce company based in Ottawa, Canada. Platforms that reach more than 10% of the EU’s population (45 million users) are considered by the Commission to be ‘systemic in nature’ and are subject not only to specific obligations to control their own risks, but also to a new oversight structure.

This new accountability framework will comprise a board of national Digital Services Coordinators with special powers for the Commission in supervising very large platforms, including the ability to sanction them directly.

This is not the European Commission’s first attempt to rein in the powers of the big tech companies. In 2018, Twitter was fined €450,000 by the Irish data regulator for breaching Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). It was the first time a financial penalty had been issued to a US tech firm under the GDPR, which was the EU’s 2018 attempt to achieve what it now hopes the 2020 proposals will.

In this case, Twitter had failed to notify Ireland’s Data Protection Commission of a privacy breach within the statutory 72-hour period. At the time Twitter owned up and accepted its punishment without demur, while other tech companies by and large accepted the 2018 regulations, although Google was concerned that it could prevent it from carrying an advert for, say, a restaurant, alongside its menu and the ability to reserve a table. That was then and this is now: the new 2020 regulations are a lot tougher. The 2018 legislation was part of the ‘Digital Single Market Strategy’, based on the belief that there was “an asymmetry between the market power of the platforms and the large number of (especially small) businesses that use them.” The Commission recognised the importance of platforms for entrepreneurship, trade and innovation, but was concerned with the dependence of businesses on those platforms. In particular, the Commission pointed to abrupt changes to terms of use, delisting or suspending accounts without clear reasons, lack of transparency regarding rankings on platforms, and ‘most favoured nation’ clauses.

THE BIGGER THEY COME, THE HARDER THEY….FIGHT BACK?

In the EU, concern was mainly over how powerful the large tech companies have become, partly because they are making life much harder for smaller start-ups in the same field. Google’s original motto was “Don’t be evil”, but it’s something the current directors seem to have forgotten or at least to be ignoring. In any case, it was never “don’t be greedy”. One way of tackling that, believes the Commission, is to put an end to the practice of “self-preferencing”. This is when, for instance, someone makes an on-line search using an Apple on-line tool and the first options it suggests (and the most numerous) are for other Apple products.

This leaves alternative app developers struggling for the oxygen of publicity: people won’t select or buy what they don’t know about, even if it’s better. Another change the Commission wants is for companies like Apple and Google to give users the chance to uninstall apps that came ready-installed in the product they’ve bought. This reflects action in the United States by the Department of Justice, which took action in October against Google, claiming that the company ties up phone makers, networks and browsers in deals that oblige them to make it their default search engine. Google already has something like 90% of global market share, so there seems to be little excuse for such restrictive marketing practices. Advertising on Google pays for everything. Evil? Well, you’d have to make up your own mind. But restrictive and extremely profitable it certainly is.

The other part of the plan is to force digital companies to take down offensive or harmful content without delay, with big fines being imposed if they fail to do so. Commissioner Vestager, in announcing the new rules, said “The two proposals serve one purpose: to make sure that we, as users, have access to a wide choice of safe products and services online. And that businesses operating in Europe can freely and fairly compete online just as they do offline. This is one world. We should be able to do our shopping in a safe manner and trust the news we read. Because what is illegal offline is equally illegal online.”

True, but much harder to call to account, given that much of the most offensive content originates abroad. Russia’s famous St. Petersburg troll factory is still active, disseminating untruthful and misleading material, even suggesting that a COVID-19 infection is not dangerous and also some proposing deadly ways to self-medicate (swallowing bleach is not a great idea).

Anyone who has bought a computer from one of those out-of-town retailers (and often if they have bought on-line) will have experienced what is called ‘bloatware’. Bloatware is to your mobile phone or computer what junk mail is to your mailbox, except that it’s harder to spot and more difficult to get rid of. It means software programmes and apps installed in your new device without prior permission that may make it harder to install the apps you actually need and want whilst clogging up your new device’s memory. The vendors clearly get a kickback for putting the stuff there and will tell you that the apps are all helpful and useful and that you’ll get great service from them. You may even find the occasional one helpful, although you might have preferred an alternative supplier. Some kinds of bloatware contain games which the new owners of the equipment are lured into playing, only to discover that to progress beyond a certain point costs money. In fact it’s sometimes a deliberate lure intended to encourage people to take up gambling, which makes it pretty nasty stuff. What bloatware also does, of course, (apart from boosting the vendor’s profits) is to take up so much memory that everything else operates more slowly. Uninstalling it all is probably a job you won’t fancy, being needlessly time consuming for those who are tech-savvy and a worrying chore for the rest of us. Sadly, as far as I can see, neither the DSA nor the DMA directly targets this issue, although both should help to clamp down on the practice. “The business and political interests of a handful of companies should not dictate our future,” said Vestager and Breton in a written statement, “Europe has to set its own terms and conditions.” Let us hope those conditions exclude dangerous bloatware.

MOVING WITH THE TIMES

Technology, of course, has moved on apace. When I started working for the BBC, initially as a freelance technical operator (we were called ‘station assistants’ in local radio) and occasional presenter, our various channels were controlled by knobs that turned. These “faders” were called ‘pots’ (potentiometers) and were not smart quadrant faders. We checked our output levels on a peak programme meter (PPM) to ensure they were correct. That was analogue, of course, not digital, and levels were, in fact, much easier to control. We had to set things to ‘zero’ level, but these days the level in decibels, when reckoned digitally, involves logarithms, so zero dB in analogue terms comes out at something like -10 dB or even -12dB in digital. I know it’s harder to get levels exactly even these days and electronic circuits designed to achieve that end seldom do, in my experience. That could be why different programmes on your television are broadcast at different volume levels, although control by a sloppy audio engineer is more likely to be the cause. After all, the official advice is to record at the highest level possible until you start to get what’s called ‘clipping’ – a form of audio distortion. These days, with people listening to compressed audio on tiny devices, the words “high fidelity” seem a bit irrelevant.

I was recently sent a photograph by a near-contemporary of mine who still presents radio programmes. His control desk was quite unrecognisable to me, with a computer screen controlling every action, including the music being played, and no sign of record turntables, open-reel tape recorders or jingle-playing machines. Even the faders were virtual. I was not tempted to return to working in radio. When I started, BBC local radio had just started to use portable Uher reel-to-reel tape recorders for interviews. Being a freelance, I bought one of my own (second hand and from someone who had to leave the country hurriedly, so was selling it cheaply) which I still have. I haven’t used it for years, relying now on a digital sound recording device which, unlike the Uher, I can no longer repair in the field with a screwdriver, a dollop of solder and a box of matches. These days I record Zoom interviews for clients from the safety of my own home, using two separate video cameras to shoot ‘cutaways’ – alternative angles with which to liven up the finished product when I edit the thing together. It’s a world away from what I first trained to do.

Zoom interviews, of course, rely on the Internet and are widely used in the audio-visual media these days. Zoom is the media-saving device of the age, without which, in the current pandemic, news reporting on TV and Internet platforms would simply cease. I would not like to see it being restrained by any new regulations but that really doesn’t seem very likely. My only fear is that contacting people by Zoom will become so familiar and ubiquitous that journalists and others will no longer bother to travel at all. That would be a great loss for humankind. Indeed, if I had my way, I would like to persuade everyone, everywhere, to spend some time living in another country, preferably while they’re young and adventurous. It helps to break down barriers and it broadens horizons.

Perhaps the same applies to legislation. It’s certainly being predicted that the EU’s strict new regulations for the tech giants will have an impact far beyond Europe. The companies themselves may not want that, but the EU is a massive market and if the large operators have to modify the way they conduct themselves to suit it, it may prove more cost effective to apply the rules everywhere. That way, the DSA and DMA may end up affecting how business is carried out not only in the EU but also in the United States and elsewhere. Vestager, when presenting the two proposed pieces of legislation, admitted that they were complicated and very different from each other, but she used an interesting metaphor. She reminded journalists that the world’s first traffic lights were installed in Cleveland, Ohio, to address a growing problem brought about by new technology: the invention of the motor car or automobile. That momentous moment in history took place on 5th August 1914, at the corner of Euclid Avenue and East 105th Street. It was based on the ‘Municipal Traffic Control System’ design by James Hoge which was later patented in 1918 and was worked using electricity. Vestager said it was a fair analogy because at the time traffic was increasing rapidly, just as Internet traffic is today. She said it was necessary to create rules “to put order in the chaos”. The traffic light made the streets of Cleveland safer, which is what she is doing for digital services. “That is what the Digital Services Act is all about,” she said, “creating the rules, making the online world as safe, reliable and secure for all users of the digital roads. Because we should all be able to trust what we do online. To navigate the web without being confronted with terrorist propaganda. And feeling certain that the toy we buy online is just as safe as the toy that we buy in a bricks-and-mortar shop.” Vestager made it clear that she will not hesitate to come down hard on those who break the new legislation, even down to breaking up the companies.

It is not yet a done deal, although it almost certainly will be. First, it has to be gone through by European Parliamentary committees, which will undoubtedly propose changes. They will be lobbied, too, by ‘interested parties’ that can foresee it impinging on their bottom lines and making life more difficult. While Vestager, in her rôle as Hercules, is busy diverting the river Alpheus, the longest river in the Peloponnese, through the stables of Augeas, you can bet that many a latter-day Augeas is dreaming up ways of not paying the promised percentage and getting out of having to pay. Hercules agreed to clean out the stables of Augeas, you may recall, befouled with years of muck from his vast herds of oxen and goats, on condition that if successful he would receive one tenth part of the livestock as his reward. Augeas, who had been one of Jason’s Argonauts and therefore a hero is his own right, reneged on the deal, claiming Hercules had used artifice which had not involved any personal cleaning work, although Augeas’ son, Phyleus, supported the hero’s claim. Augeas foolishly stood firm: it was a declaration of war. According to my 1827 copy of Lemprière’s Classical Dictionary, Hercules won, deposed Augeas and elevated Phyleus to his throne, although the book suggests Augeas was spared at the request of Phyleus himself. Interestingly, after his death Augeas received all the honours due to a hero. So the big tech companies may yet emerge from this intact, or sufficiently intact, and you can bet they will still find ways to minimise the impact of legislation and make a profit. Believing one can subdue them for long is probably a myth.