Narco submarine seized by the Spanish National Police © Nrf

“I am not what you call a civilised man!” cries Captain Nemo in Jules Verne’s ‘20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’. “I have done with society entirely, for reasons which I alone have the right of appreciating. I do not, therefore, obey its laws, and I desire you never to allude to them before me again!” He was referring to his strange and lonely life aboard his self-constructed submarine, the Nautilus, and explaining it to French marine biologist Professor Pierre Aronnax, who, along with a Canadian harpoonist, Ned Land, he had just taken on board, somewhat against their will. They had been hunting the alleged ‘monster’ in a ship the Nautilus had attacked and sunk. Taking his ideas from scientific devices shown at the Paris Exhibition of 1867, long before undersea voyages were considered feasible, Verne describes his vessel, which is also effectively his bachelor pad, as long and cylindrical with a double hull and interior watertight compartments. It is supposed to be both impenetrable and unsinkable and tapered like a cigar at each end. Verne got the idea of electric propulsion from the exhibition, too. Nemo uses it to sink other vessels, earning a reputation as a sea monster and deterring local shipping. Some witnesses described it as being like a giant narwal, although real narwals rather lack portholes.

The book, classified as science fiction, was basically anti-imperialist. Nemo had been driven to his solitary but deadly existence by the invasion of his home country and the slaughter of his wife and family at the hands of an imperialist nation bent on plundering resources to which they had no right by means of conquest. The book is set in 1866 and in the late 19th century there were several imperial powers vying to plunder the world’s riches at the time, to the everlasting detriment of poor peoples, so it’s hard to know which one Verne, a Frenchman, meant. Britain seems his most likely target but it may have been his own country he was getting at. The criminals using submarines today have no such excuse for their activities.

Nobody has deprived them of anything, except their liberty when they’re caught by the law enforcement authorities. It is purely for personal gain, and they are becoming increasingly inventive, not to mention murderous. The surface vessels they often used to transport drugs across the oceans were being spotted and intercepted by coastguards rather too often for comfort, so they took the Nemo route and went beneath the waves. The drugs traffickers have been using submarines or ‘semi- submersibles’ for several years, possibly as many as 15, but the vessels are getting more and more sophisticated.

One discovered by Spain’s National Police in March 2021, was 9 metres long, 3 metres wide and designed to carry 2 metric tonnes of illicit cargo. It was found by officers in a warehouse in Málaga, on Spain’s glamorous and popular Costa del Sol. The sub is made of fibreglass and plywood panels, attached to a rigid structural frame. It has three portholes on one side and is painted light blue, making it hard to spot in a wide expanse of ocean. It was designed to be powered by two 200-horsepower engines, operated from inside the vessel, so it would have been quite fast. At a press conference in San Roque, in southeast Spain, National Police Chief Rafael Perez said the vessel had never been used but he believed it was designed to ferry drugs to a mother ship and return to port. Perez thought its most probable cargo would have been cocaine, because marijuana is more often smuggled in trucks. Submarines have been used by smugglers before, but this was the first one to be found under construction in Spain, or, indeed, anywhere in Europe.

The police operation resulting from the find succeeded in seizing hundreds of kilos of cocaine, but also hashish and marijuana being produced in various parts of Spain. 52 people were arrested. The whole operation involved not only Spanish police but also law enforcement officers from Colombia, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Portugal; up to 300 officers in total.

GOING DOWN

According to the Moroccan Arabic-language newspaper Assabah, it’s believed the vessel was designed to carry various loads of narcotics across the Strait of Gibraltar. For the law enforcement authorities involved, capturing the sub was the icing on the cake. During the operation, 47 homes were raided and a very sophisticated drug laboratory was found in Barcelona, together with a 15-metre fibreglass speedboat, 400 kilos of cocaine, 700 kilos of hashish and more than €100,000 in cash. The drug trafficking gangs are not short of money and seem to be copying the drug traffickers that target the United States. The submarines they build follow a similar pattern.

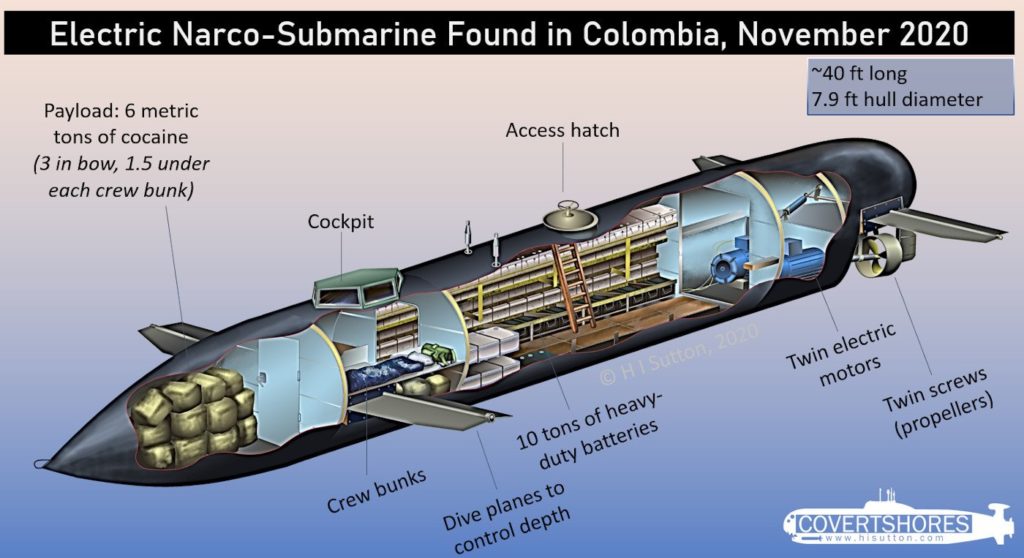

Take as an example the fully-submersible vessel discovered by the Colombian Navy, aided by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), in an artisan boatyard on Colombia’s Cucurrupi River, in the Chocó area. This submarine was more than 12 metres long and it was powered by an electric motor, making it hard to detect with underwater listening devices when it’s underway, while its low surface profile would make it hard to spot with radar, sonar or with binoculars. It would not have been cheap, which goes to show the wealth of the traffickers. The vessel would have been capable of carrying 6 tonnes of cocaine with a street value of $120-million (€102-million).

The vessel was far larger than other previously discovered ‘narcosubs’, as the DEA has dubbed them; other examples have only had the capacity carry a quarter as much.

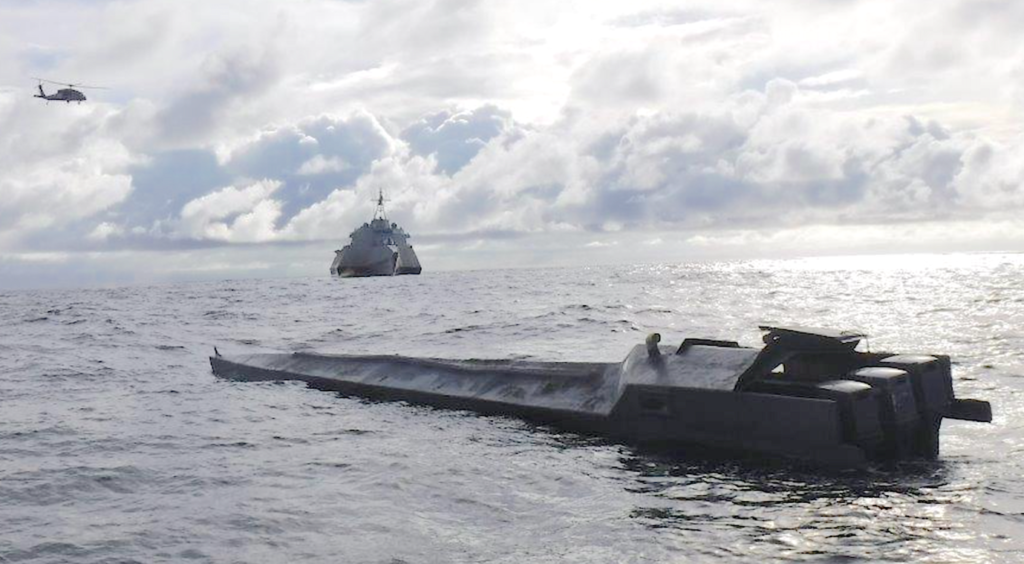

In December, an American warship intercepted one of the smaller, more common subs in the Eastern Pacific. Rather than a fully submersible vessel, the one intercepted by USS Gabrielle Giffords last December, operating with a detachment of US Coast Guards aboard, was what’s called a ‘low-profile vessel’ (LPV). Its low freeboard (the distance between the waterline and the main deck or weather deck of a ship or between the water level and the upper edge of the side of a small boat) means that its profile above the water is small enough to escape notice by law enforcement officers, although not on this occasion, of course. According to US Naval Institute News on 14 December 2020, “This is a mass-produced design which has been seen many times before. In fact, it is at least the 19th of this exact model reported since 2017.

It was built from roughly crafted fibreglass and is powered by three of the ubiquitous Yamaha Enduro 2-stroke outboard motors.” Not so sophisticated, then, nor anything like as quiet, but clearly being pumped out in great numbers in clandestine boat-building yards to service the narcotics gangs. The crew sleep in the cargo hold, lying on the cocaine bales. Halfway towards the bow, the central tunnel that serves as access, as well as providing an additional place to stash cargo, then leads into the main cargo hold, in front of which are more fuel tanks. According to the US Navy, the interior of the subs is usually cramped, smelly, unhygienic and claustrophobic, but despite this the drugs cartels never have difficulty recruiting crews. In this particular incident, the 3-man crew was arrested and the cargo – 2,810 kilos of cocaine – was seized. The cocaine, in one kilo bricks, was wrapped in plastic sacks to make the bales. It had a street value of more than $100-million (€85-million).

GOING UP

The US Navy and Coastguard believe that the size of the cargo, which was much larger than usual, shows that the drug trafficking gangs are trusting the submarines with larger cargoes. The massive sub found in Colombia by the Colombian Navy was, after all, powered by an electric engine and carrying 10 tonnes of batteries to give it a considerable range in virtual silence. It’s been hypothesized that the reason for the larger loads is not just greed (although that undoubtedly plays a part) but is the result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is seriously disrupting other traditional routes, such as commercial flights and shipping. For those of a nautical mind, the subs feature a fully enclosed cylindrical hull with a hexagonally-shaped viewing port to aid navigation and four dive planes to allow it to submerge when threatened with discovery. Almost all of the subs also have satellite navigation capacity and long-range HF-SSB radio communication equipment. The very informative Blue Seas website for dedicated mariners describes the facility like this: “The Marine MF/HF-SSB radio is a combined transmitter and receiver much like your VHF. The primary difference between the two is the frequency ranges that they operate in. Typically Marine MF/HF-SSB radios operate in the frequency range of 1.6 MHz to 30 MHz. Probably, the most important concept here is that: ‘They allow the operator to select a frequency based on atmospheric conditions to establish communications over varying distances.’” For the curious, HF-SSB stands for ‘high frequency – single side band’.

Now that they have become almost the only fairly reliable means of transporting narcotics from their origins to their markets, the subs are carrying more and more. They must be worth paying for, from the traffickers’ point of view: the one captured in Colombia had enough battery power to let its silent electric engines run for 12 hours at up to 3 knots, enough to travel up to 36 nautical miles, depending on conditions, so it was more likely to be seen as a link between a larger cargo vessel and the shore. Its building cost has been estimated at $1.5-million (€1.27-million), but the largest load of cocaine found by the crew of a US Coast Guard cutter on board a semi-submersible was 7.7 tonnes, which would be worth around €131-million on the streets, making the cost of construction look insignificant. The United States authorities believe that most of the subs cost anything up to $2-million (€1.7-million) to build, but a single trip carrying cocaine can generate more than $100-million (€85-million) in profits if it gets through. Most of them do.

In the summer of 2017, the Colombian military captured a drug sub with smaller, quieter electric engines and more than 100 batteries. In the Colombian rainforest, under its canopy of trees, the drug traffickers’ boat builders have been creating vessels for a quarter of a century. That’s where the narco-subs are made. In one raid on such an operation, the authorities found thousands of euros of materials, a paid labour force and – sometimes – Russian submarine designers. It would seem that Vladimir Putin’s desire to undermine the democracy of the United States extends to providing military experts to aid the drug gangs. This from a country that severely penalises drug dealing at home. It smacks of rank hypocrisy on Putin’s part. According to the DEA, as reported in US Naval Institute News, Colombia produced up to 910 metric tonnes of cocaine in 2016, a 32% increase on the previous year, and a third of that travels in illicit home-made submarines to users and addicts in the United States. It’s believed that some of the larger subs can reach speeds of 9.7 knots (18 kilometres per hour) and carry up to 10 tonnes of narcotics for a distance of more than 3,000 kilometres. In 2019, Spanish authorities apprehended a 20-metre semi-submersible containing more than 3,000 kilos of cocaine. The semi-sub had made the journey all the way across the Atlantic. As for the comfort of the crew, it’s worth noting that none of the subs so far discovered contained a toilet. Captain Nemo would be horrified.

Most of these stories relate to drugs being trafficked to markets in the United States, but the submarines are increasingly being used in trafficking to markets in Europe, with Spain a prime destination. European law enforcement agents are doing their best to shut them down, despite the difficulty of finding them, let alone intercepting them. However, when the crews of the submarines see the approach of law enforcement vessels, they are under instruction to scuttle their subs, together with their cargo. They can then bob about in the water in the knowledge that the laws of the sea will oblige the navy or coastguard officials to rescue them. With no actual evidence of their criminality in sight, the officers have no choice but to set them free. As for the subs, it would appear that some of the larger and more expensive ones are intended for multiple trips, with what are called “sacrificial zinc anode bars” fitted to their hulls to reduce the effects of seawater corrosion of the metal parts. It’s clearly big business for the drug gangs; it’s been estimated that some 1,000 submarines are now in use for transporting narcotics. Often, they make the return trip carrying guns for South America’s many gangs and terrorists.

However, there are differences between the submarines favoured on either side of the Atlantic. On the American side, the subs have been getting smaller and, in some cases, appear to have been home-made. In August 2020, however, the Colombian Navy discovered the largest narco-sub yet seen. It was destroyed on the spot but officers reported it to have been about 30 metres long with a beam of 3 metres and capable of carrying 6 to 8 tonnes of narcotics. Technically, it was a low-profile vessel (LPV), rather than a fully submersible type and it would have ridden sufficiently low in the water to escape notice. The authorities have given them the classification SPSS, short for self-propelled semi-submersibles. The location of its discovery, off the Pacific coast of Colombia, suggests it was to be used to ferry drugs to Mexico for onward transportation to the United States, but its size could hint at an intention to use it further afield, perhaps even as far as Australia. Alternatively the same boat builder, whose handiwork has been recognised in other more advanced submersibles and semi-submersibles, could be sailing his products along the Amazon and across the Atlantic to Spain. The large sub intercepted in Spain in November 2019 bears the signs of the same boat-maker’s handiwork. Even when the authorities spot one of the subs at sea, only about one in ten has been successfully intercepted. The scuttling, followed by calls for help, means many crews get away with it. With so many bales of narcotics being committed to the depths of the ocean, one can only imagine the number of spaced-out, fuzzy-brained fish and lobsters there are out there: the doped-up denizens of the deep.

The sinking of a semi-submersible with 3,050 kilos of cocaine in the Aldán estuary in Spain confirmed the origin of the vessel from a South American clandestine. © Xoan Carlos Gil

UNDERSEA, UNDERHAND

To date, narco-subs, as the DEA calls them, have been more common in the Eastern Pacific and the Caribbean, and it’s known that one attempt by traffickers to build one in Europe was a failure. With greater expertise, it would seem the skill has migrated, helped perhaps by successful sailings of Colombia-built submarines across the Atlantic. The crew members arrested escaping from the vessel off Spain had been at sea, they admitted, for 20 days, although they would not name their point of departure, nor if they had made the entire journey in the sub or stopped along the way, but it seems likely the vessel left from somewhere in Brazil to make its 5,800-kilometre journey. That is a very long way for a cramped and uncomfortable submarine. According to H.I.Sutton, the well-informed writer on maritime defence issues who has made a study of narcotics submarines, the journey may have been broken at the Cape Verde Islands or the Azores, where the Brazilian crews would have been able to communicate in their native Portuguese. Sutton has even published a book about the narco-sub issue. He thinks it’s more likely that subs from South America then go near to the Azores to meet a cargo ship known to have set off from somewhere the authorities consider a ‘safe ‘ port. There, they transfer the cargo to the large vessel, only for it to be switched to another sub when it gets near to Spain. Or, perhaps, the UK or Ireland?

Business Insider reports than in November 2020, 11 members of a gang that specialised in building boats for drug traffickers were arrested. Their operation was allegedly under the protection of the Colombian terrorist group, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, or ELN). The boat builders had apparently achieved so much fame in the criminal underworld that other groups were contacting them to employ their skills. The website quotes Admiral Hernando Mattos, commander of the Colombian Navy’s anti-narcotics Poseidon Task Force, as telling the newspaper El Tiempo that “it is not uncommon to find that drugs from two or three networks are transported in one … submarine so that they can jointly cover the shipping and costs of these vessels, which can reach up to $1million (€0.85-million).” That is a Conservative estimate; the cost is often double that figure. Even so, submarines have become a mainstay for Colombian organized crime groups. “In 2019,” reports Business Insider, “23 such vessels were confiscated. And between January and August 2020, 27 were seized between the Colombian coast and international waters.”

Submarines travelling from South America all the way to Europe are a new concept and a worrying one for law enforcement agencies. The low-profile semi-submersibles known as the LPV-IM type – in other words ‘low profile vessel – inboard motor’ – are very hard to detect, travelling with a vast load of cocaine, plenty of fuel and at slow speed. They can either travel directly to Europe or Africa or else unload their cargo onto yachts and merchant vessels, including tugboats. In transporting drugs across Africa, the gangs sometimes have the help of terrorist groups such as Hezbollah, Al Qaida and others, just as in Latin America the boat builders benefit from their association with the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), the Sinaloa Cartel and other terrorist groups, happy to provide armed assistance in return for cash.

Europe is starting to copy the United States in its response to the threat: in 2007 it set up the Maritime Analysis and Operations Centre – Narcotics (MAOC (N)) in Lisbon, yet so far it only has the support of France, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Portugal and the UK. The UK’s long-term involvement may be doubtful, too, now that it is outside the EU. It does have the support of the European Commission, EUROPOL, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the European Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), The European External Action Service (EEAS), the European Defence Agency (EDA), EUROJUST and FRONTEX, all of which have observer status. Europe will need that, and more: it would make sense for other countries with drugs problems to get involved, such as Belgium and Germany, one would think. The narcotics smugglers have proved themselves very clever; the authorities need to be cleverer still. It would be best of all, perhaps, if the craving for illicit drugs could be curbed, but that seems unlikely. I leave the final words to Jules Verne’s immortal anti-hero, Captain Nemo: “However, everything has an end, everything passes away, even the hunger of people who have not eaten.” Or, perhaps, snorted cocaine?