There was nothing that we would recognise as ‘a creature’ wandering through the shallows of the Ediacaran seas. Indeed, ‘wandering’ may be too modern a term to be appropriate for things that still reproduced by cloning and that, in many cases, oozed, rather than walked or crawled, across the sandy or muddy sea floor, eating even smaller marine microorganisms. Five hundred and fifty million years ago life was still struggling to assert itself on this globe of ours, at that time devoid of land-based living things. The tiny fossil trilobite I keep on my desk would not creep about on a sea floor for another one hundred million years. But those microorganisms I mentioned that definitely did exist were vital: it was cyanobacteria that produced oxygen, after all, as a by-product of early photosynthesis, and that oxygen would swell in volume over the millennia and prove to be vital for the biota that followed, like ferns, eoandromeda jellies, charnia, dickinsonia, and eventually us. These microorganisms were made up of plankton: zooplankton in the case of what we must class as ‘animals’ (based on the shapes of their cells) and phytoplankton for those, such as algae, we would class as ‘plants’. There were a few microbes in the mix, too. Those tiny microorganisms, too small to be seen without a microscope, would continue to be vital to the present day. They often got mixed in with the mud and silt on the sea floor and then buried when a landslide brought a heap of sediment down whatever river discharged nearby. Only the more energetic creatures of the time would have the energy to escape; those things left behind, living but not in a way most of us would readily recognise, would become subject over the eons of time to heat and pressure in their anaerobic tombs, and that would gradually turn them into hydrocarbons, trapped under impermeable rock. It’s widely believed (although unproven) that the plants and creatures of the Ediacaran era died out and were replaced on the tree of life when the Cambrian era began, bringing with it creatures of a predatory nature that ate them. History has a habit, it seems, of repeating itself.

Bringing the resulting natural gas that developed from these long-dead microorganisms to the surface is – not surprisingly – big business. Very big indeed. And there is no shortage of predators. For Azerbaijan, the industry of extracting fossil fuels is very old; the country was exporting oil from as long ago as the 7th century BC and is sometimes described as the world’s most ancient oil-producing country. Now it’s being asked to produce more. The reason for the extra demand is, of course, Russia’s vicious invasion of Ukraine. This has resulted in the West trying to reduce its dependence on imports from Russia. The European Commission has talked of replacing it with liquid natural gas, LNG, but Europe would need a lot and would face fierce competition to obtain it. The Commission has estimated that it could obtain some 10-billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas from other pipeline sources, getting another 50-bcm from LNG. But 50-bcm would be around 10% of the annual global supply and Europe won’t be alone in trying to secure a share.

According to the Brussels-based think tank, Breughel, Russian gas mainly arrives along three routes: Nord Stream (the original one, since Nord Stream 2 was never signed off and now seems unlikely ever to be), Yamal, which comes through Poland, and Turkstream, which comes via Turkey. Russian President Vladimir Putin has threatened to turn off the gas supply if Europe turns its back on Russian oil. He may, of course, although the Russian economy is suffering from all the boycotts and sanctions and turning off its gas exports to Europe would hurt it further, despite Putin’s huge war chest. It’s believed that his war in Ukraine is costing Russia $20-billion (€18.08-billion) per day, while the country’s economy is actually shrinking, largely because of rampant corruption.

Putin and his oligarch friends have syphoned billions out of their country’s economy to fund their lavish lifestyles and to pay for pleasure palaces, ludicrously elaborate yachts and to treat pliable but influential Western politicians to luxurious holidays. Even so, Russia’s GDP in terms of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) comes to an estimated $4.1-trillion (€3.7-trillion), the second largest in Europe and the 6th largest in the world. So, Putin can afford to attack his neighbours; Alexander Lukashenko, the accident-prone President of Belarus, appears to have revealed a map suggesting that Putin has his eyes on Moldova next.

PIPING IN THE FUTURE

Which brings us back to the subject of energy. The EU imported energy from Russia worth $108-billion (€99-billion) in 2021. That’s a reduction on 2012’s figure of $173-billion (€157-billion) but it’s still a lot of gas. If the figure is to be cut further, Europe needs to find an alternative source, even if it’s unlikely ever to be able to turn off the taps completely. After all, Europe is heavily dependent on Russia for energy, with two-fifths of its gas and more than 25% of its crude oil originating there.

Step forward, Azerbaijan, which increased its production of natural gas by 36% between 2017 and 2019, and in 2021, Azerbaijan oil and gas condensate production rose by a further 0.1 percent from the preceding year to an impressive 34.581-million tonnes. Natural gas output increased by 18.1 percent to 43.864 bcm.

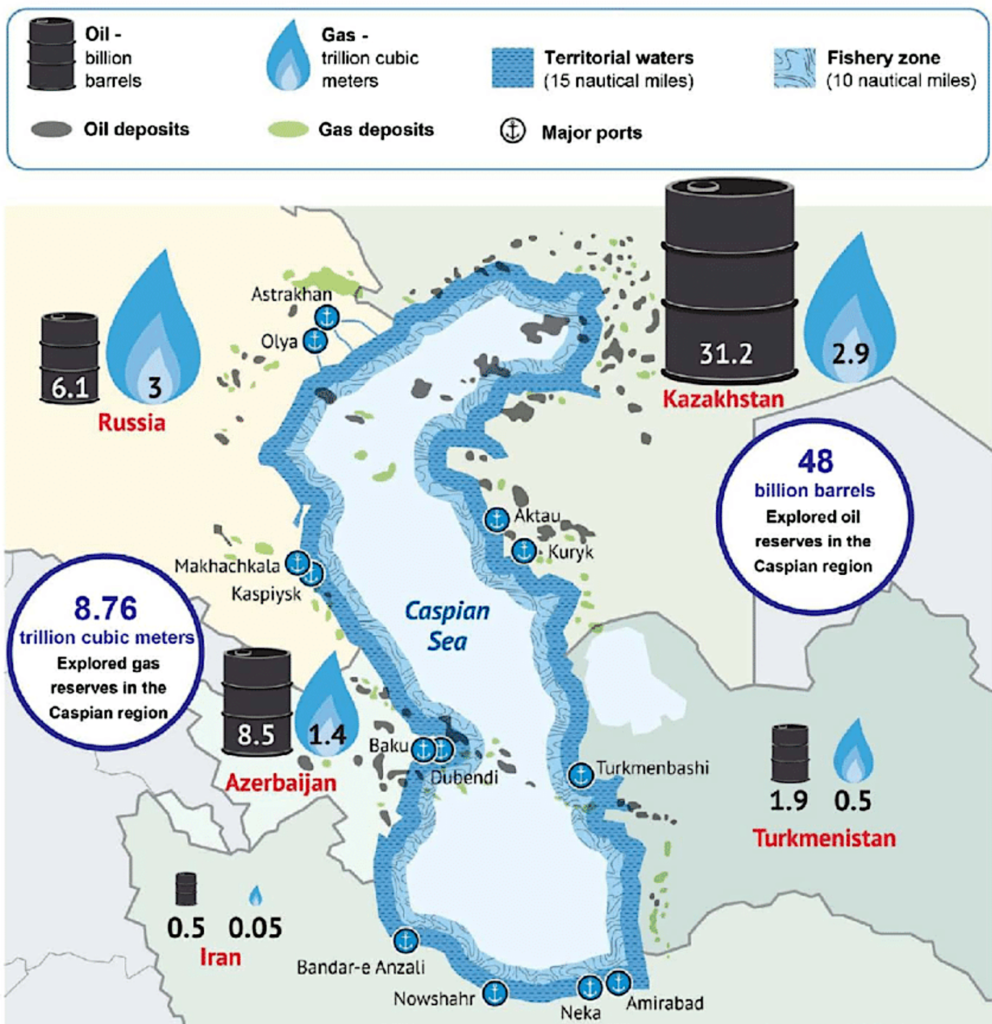

It also has a new pipeline link to Europe. The gas mainly comes from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz field, situated offshore in the Caspian Sea. There are several pipelines in service, the latest completed in October 2020. Azerbaijan also has the South Caucasus pipeline (SCP), connecting to neighbouring Georgia and Turkey, from where it is connected to the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline. This in turn links to the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), feeding gas to Greece and, through Albania, to Italy.

Italy is the largest buyer of Azerbaijan gas, it was revealed in a report from TAP AG. The report says that Azerbaijan has exported 10-billion cubic metres (bcm) through the TAP pipeline, with 8.5-billion cubic metres going to Italy. In a TAP AG press release, Managing Director Luca Schieppati said: “10-bcm is a symbolic but important milestone. Just over a year after starting commercial operations, we have provided our shippers with efficient, reliable and uninterrupted transport services, making an important contribution to Europe’s energy security and supply diversification. Now we can reach TAP’s full transport capacity of 10-bcm per year. In addition, we can add additional capacity through short-term auction.”

According to US Energy Information Administration, Azerbaijan’s Energy Minister, Parviz Shahbazov, has said that his country’s gas exports to Italy this year will reach 7.4-bcm. TAP’s Head of Commercial Operations expects the field’s gas output to double as development continues.

It’s certain that cutting off supplies of Russian energy would cause pain for Europe, although the Brussels-based economic think tank, Bruegel, believes it would be temporary; Europe would adjust. The United States, Canada and the UK have placed embargoes on Russian energy, but they are less dependent than the European Union and can easily afford to. Instead, the EU has launched what it calls REPowerEU (yes, I know it’s a silly name) which aims to reduce imports of Russian gas by two thirds by the end of this year. Its founders want Europe to be completely independent of Russian fossil fuels before 2030. According to Bruegel, a number of market players have been paring back their purchases of Russian oil and gas, fearing damage to their reputations or the possible impositions of further sanctions. In December 2021, Russia exported 5-million barrels per day (mb/d) of crude oil and 2.8 mb/d of oil products, with more than 70% going to European and US markets. Overall, oil and petroleum products accounted for 37% of Russia’s export revenue last year.

The Chinese believe that the desire to cut reliance on Russian hydrocarbons will help Chinese exports by boosting demand for solar and wind power installations, possibly quadrupling it by 2030. That would mean 480 gigawatts (GW) of wind power and 420 GW of solar farms, raising the EU’s installed solar energy capacity to 585 GW in 2030, all in a bid to compensate for the loss of 20-bcm of gas from Russia. The withdrawal of Russian energy, though, would cause a massive global shock, with some 3-mb/d of Russian crude oil and a further 1-mb/d of oil products being taken off-line. It seems unlikely that other producers could make good the shortfall. The strategic oil reserves of 1.5 billion barrels currently held by members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) could only compensate for one year, at best. Dipping into it would have to be accompanied by a serious search for alternative sources. The EU requires its member states to retain emergency stocks that are equivalent to 90 days of net imports or 61 days of consumption, whichever is higher.

The website of “The Conversation” lays some of the blame for the difficulty in resolving the Russian gas issue at the EU’s own door, for making over-complicated rules. With Russian gas making up around 40% of the EU’s gas consumption, EU leaders have been looking at alternative gases, such as hydrogen and biogas, but that’s not the answer, according to the website. “The more efficient solution would be to swap fossil fuel burning boilers for alternatives that run on electricity, such as heat pumps. These new proposals supplement the original 2030 climate target plan, published in September 2020.” Of course, the electricity itself will need to be generated somehow. It will be far easier to replace Europe’s imports of crude oil than it will be to replace gas. Much of the crude still comes by ship, whereas the gas is piped.

TURN ON THE TAP (WHICH TAP?)

In total, the EU must look to replace some 155-billion cubic metres of natural gas, but The Conversation argues that the EU is wrong to step up production of alternatives, such as “renewable gases”, by which it means things like hydrogen and biogas, whilst seeking new routes to bring gas into the European Union from Qatar, the United States, Norway, Algeria and, of course, Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, the Commission wants to see Europe producing between 25 and 50 billion cubic metres of hydrogen by 2030, which will require massive and very costly infrastructure investment, while getting an extra 18-billion cubic metres of biogas by the same target date, which would mean paying farmers to expand their production of crops in ways that would harm the environment, such as by the massive use of chemical fertilisers. The birds, mammals and pollinators would not be happy. The website argues that switching to heat pumps would be less environmentally damaging.

It’s known that Israel has massive supplies of natural gas but they are largely untapped. The question is: how would the gas – supposing Israel starts utilising it – be transported to Europe? On 9 March, Israel’s President, Isaac Herzog, visited Ankara amidst speculation that if it taps into its massive Leviathan gas field, it will be able to pump it to Europe through Turkey, although arranging and constructing the required infrastructure would take time and be expensive. Azerbaijan’s Energy Minister, Parviz Shahbazov has confirmed that his country is sitting on some 2.6-trillion cubic metres of gas, which he told journalists would be: “enough for its neighbours and European countries”.

EU Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson has reached an agreement with Baku to “step up our partnership”. With the best will in the world, however, Azerbaijan’s gas reserves will certainly help but cannot take the place of the gas coming from Russia. Even if its goal of increasing output to 20-billion cubic metres per year is realised, it’s still only a fraction of the volume coming in from Russia. So, Russia still holds the whip hand on energy. Indeed, from Europe’s perspective, it’s rather worse than that. Russia also supplies part of the essential supply chain for the nuclear industry.

That matters more than it may appear at first glance. 32 countries use nuclear power – in France’s case, it gets 69% of its electricity from nuclear power, while Ukraine gets 51%, Hungary 46%, Finland 34% and Sweden 31%, according to India’s excellent “The Economic Times”. Virtually all of the world’s 440 commercial nuclear power stations obtain at least some of their nuclear fuel from Rosatom, a Russian state-run enterprise. Relatively few companies possess the facilities or the expertise to process raw uranium ore, enrich it and turn it into fuel rods. Rosatom is one of them and a leading exponent. Raw uranium ore is not found just anywhere. Kazakhstan produces some 40% of the global supply, with smaller amounts coming from Canada, Australia and Namibia, but most of it is shipped through Russia for processing before it hits the world market. Even the US relies on Russia for up to 20% of its yearly uranium supply. China buys from Russia, too. If Russia were to retaliate in response to Western sanctions by withholding supplies, The Economic Times has calculated that it would start to affect the US and Europe “within 18 to 24 months”.

Before everyone in Europe starts cheering about Azerbaijan’s gas, it’s worth noting that there are political problems. Azerbaijan has been accused of deliberately interrupting the supply of its gas to Artsakh, also known more commonly as Nagorno-Karabakh. The disruption of supply has already affected educational establishments there, according to Human Rights Ombudsman Gegham Stepanyan. In a Tweet, he wrote that the interruption has created a lot of problems in schools and kindergartens, which rely on gas for heating and cooking. Stepanyan wrote that: “70% of hospitals in Artsakh are heated by gas, 400 patients are receiving inpatient treatment, 46 are children of different ages, 50 are mothers of new-borns and their children. Azerbaijan continues to deprive the people of Artsakh of gas supply in the absence of international reaction.” The interruption was caused by a damaged pipeline – claimed with some justification to have been deliberately caused – but it is now under repair. The row, which became yet another a war, involved Armenia and Azerbaijan, both of which claim Nagorno-Karabakh, whose own citizens call the place Artsakh. Several cease-fires have broken down (there is one in place at present that is supposed to signal the end of hostilities, although it’s unlikely to be), putting gas and crude oil exports at risk. Russia is pledged to defend Armenia, Turkey is pledged to defend Azerbaijan, while Iran also has a large Azeri minority. The two sides hardly speak to each other if they can avoid it, which creates the risk of fighting breaking out and making peace efforts fairly useless. There were sporadic low-level clashes throughout last year.

WHERE? WHAT? WHY?

Azerbaijan is a large flat area of landlocked low land with the Caucasus mountains to the north and the Karabakh upland of Qarabag Yaylasi to the west. The capital, Baku, is on the Apsheron Peninsula, which juts into the landlocked Caspian Sea, described by geographers as an endorheic basin, a drainage basin that lacks an outflow so that inflowing water is trapped there. With a total surface area of about 386,400 square kilometres, the Caspian is about 1,200 km long and 320 kilometres wide, making it the world’s largest inland sea. Some describe it as a saltwater lake instead, although endorheic basins are often the remains of larger bodies of water subsequently cut off by tectonic changes, denying them access to the sea. The Mediterranean was one before the Atlantic broke through at Gibraltar. The Caspian probably became cut off from the Black Sea by an uplift in the Miocene Epoch, some 13.8 million years ago. Previously, it may have even had links with the Barents Sea in the far-away Arctic Ocean.

The Caspian Sea itself has a complex geology, its northern sea bottom being extremely ancient and dating back to pre-Cambrian, almost certainly Ediacaran, times, when those microscopic organisms flourished before being turned into gas and oil by later earth movements. The more southerly part of the Caspian rests on a very ancient basalt crustal structure, now buried under sedimentary layers that are tens of kilometres thick. Azerbaijan, which abuts the Caspian to its western shore, is an ancient country, too: pictures on rock there – petroglyphs – show what look like dancing figures and date back to the 10th century BCE, but the country could hardly have been placed in a region so predicated towards conflict, surrounded as it is by Russia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Georgia. Most importantly, to its west is little Armenia, with whom it has been at war, on and off, since the break-up of the Soviet Union and almost certainly for far longer. Indeed, tensions between the populations led Stalin to declare Armenia an independent oblast within Soviet Azerbaijan. The population of Azerbaijan is mainly Turkic and Shia Muslim, although the country itself is secular. Nagorno-Karabakh is ethnically Armenian, by and large, and therein lies the root of the problem.

Since gaining its independence in 1991, Azerbaijan has significantly reduced poverty and has redirected the profits from its petrochemical industries to improve infrastructure. According to a report by America’s CIA, however, it is still plagued by corruption, with unfair elections, the suppression of political opposition and the abuse of human rights. The presidency remains in the hands of the Aliyev family, despite “serious shortcomings” in the most recent election that were spotted by Western observers. Aliyev’s government is trying to diversify the economy to reduce the country’s dependence on gas and oil, but the CIA says it also needs reforms to address weakness in government institutions, especially in the fields of education, health and justice.

Officially, the long-running war is over, although occasional casualties are still being reported. In a post for New Geopolitics Research Network, Benyamin Poghosyan, who chairs the Center for Economic and Strategic Studies in Yerevan, Armenia, wrote: “More than 13 months after the end of the 2020 Karabakh (war), the keyword in describing the future of Nagorno Karabakh is ambiguity. Russian troops provide a minimum level of security for Armenians living there; however, the recent incidents that resulted in the killings of three Armenian civilians have sent a clear signal that Russians cannot prevent such cases. Azerbaijan has a clear-cut strategy regarding the Nagorno-Karabakh – war has solved the conflict, there can be no return to the discussions about any status for Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan rejects the mere existence of Nagorno-Karabakh.” Which presumably means that the residents of Nagorno-Karabakh can forget the name ‘Artsakh’. This may indeed be what Aliyev would like but geographically, geologically, it is very much still there, and for gas-hungry Europe, very important indeed. Observers admit that Armenia is unlikely to do anything about Azerbaijan’s refusal to recognise the existence (and certainly a degree of independence) of Nagorno-Karabakh. As Poghosyan wrote: “Yerevan argues that the war has not solved the conflict and that the OSCE Minsk Group should resume the negotiation process based on the Madrid principles and basic elements elaborated back in 2007 or on their updated versions.” It seems very unlikely to happen, however: Baku seems to work on the principle of: “quit while you’re ahead”.

STILL WAR AND NOT MUCH PEACE

Azerbaijan recently said that it will now start to return its refugees to the regions of Nagorno-Karabakh that it captured from Armenian separatists last year. It’s believed that some three-quarters of a million Azerbaijanis were displaced when Baku lost control of the region. When the dormant conflict flared up again in September, it claimed some 6,000 lives. After six weeks of fighting, Russia brokered a ceasefire that led to Armenia ceding large areas of territory to Azerbaijan. But an ending of hostilities, of course, doesn’t mean that everyone is at peace. Armenia has, for instance, protested over the participation of UN representatives at an event organized by Azerbaijan in the Karabakh town of Shushi (also known as Shusha, in Azerbaijan. It is the capital of the Karabakh Khanate. Its official name is Şuşa). Yerevan says the UN demonstrated a lack of neutrality and has demanded that it return to its traditionally neutral position over the suspended conflict (I can’t say “ended”, because it is probably not). The acting UN Coordinator in Armenia, Lila Pieters, was requested to attend the Armenian Foreign Ministry to be informed that Armenia “strongly condemns the involvement of the UN office in Azerbaijan” in the event, on 18 March, which was held to celebrate Azerbaijan’s 30 years of UN membership. Yerevan also delivered an official note of protest. After all, Azerbaijan could have held the event in Baku. Holding it in Shushi is a bit like rubbing salt in an open wound.

Strange as it may seem, with the conflict being officially ‘over’, Yerevan still has a Foreign Ministry, which issued this protest statement over the Shusha event: “Official Baku, in line with its style, continues to wage a destructive policy aimed at legitimizing the results of its aggression against Artsakh, trying to involve and exploit the international community and various structures in that process. The organization in Artsakh’s occupied town of Shushi of a solemn ceremony dedicated to the 30th anniversary of Azerbaijan’s membership to the United Nations and the participation of representatives of the UN and its structures in this event is another manifestation of this policy. The Foreign Ministry of the Republic of Artsakh strongly condemns the holding of such an event in Shushi.” It doesn’t seem that the two sides are much closer to becoming friends.

Yerevan, however, is unlikely to prevent Azerbaijan selling its much-needed gas to Europe, with Turkey’s help. At a meeting of the Antalya Diplomacy Forum, Azerbaijan’s Energy Minister, Parviz Shahbazov, stressed again that his country’s 2.6 trillion cubic metres of gas will be enough to satisfy Europe, as well as satisfying Azerbaijan’s neighbours. “The expansion of the Southern Gas Corridor project will definitely begin,” he told the media, “And in this direction, we have started dialogue with European countries, Western Balkan countries, and other Eastern European countries.” The Anadolu Agency (AA) website reported on the meeting, where it was stressed that the biggest section of the Southern Gas Corridor, which carries gas from the Shah Deniz 2 gas field through Turkey and on to Europe, known as the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline Project (TANAP), has been transporting gas to Turkey for almost four years. Attendees agreed that the OPEC+ organisation of oil and gas producing countries is not in a position to “solve the political events, military conflicts and some other problems in the international arena.” Russia’s invasion of Ukraine fits into this impossible category, of course.

Shahbazov told AA: “I think that in the next meetings, the new situation will be discussed and the necessary decisions will be taken for the regulation of the international oil markets.” Azerbaijan’s President, Ilham Aliyev, has visited Ankara for talks with the Turkish President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan about bilateral ties and the war in Ukraine, which cannot avoid seriously affecting the trade in oil and gas. Shahbazov told AA that the two leaders discussed the Southern Gas Corridor project. “Azerbaijan has an estimated $19.3-billion (€17.45-billion) investment in Turkey, of which $17-billion (€15.4-billion) is in energy,” he said. He also talked about Azerbaijan’s plans to build various projects through the Zangezur corridor, which, he said, would be: “important not only for Azerbaijan and Turkey, but also for all countries of the region.”

The corridor is being built in the wake of last year’s flare-up in the long war over Nagorno-Karabakh, in which Azerbaijan claims to have “liberated” some 300 settlements “from Armenian occupation”. That is almost certainly not how those events are recalled in Yerevan. Remember, Vladimir Putin claims to be “liberating” Ukraine.

According to the unexpectedly interesting and informative “Weapons and Warfare” website, the upsurge in fighting should not have surprised anyone, whilst still holding lessons for the West: “In the last decade, it was no secret that Azerbaijan was steadily building up its armed forces. But, despite this, few experts predicted this month’s clear-cut military victory by Azerbaijan over Armenia. Much of this victory is credited to the technical and financial side of the war: Azerbaijan was able to afford more and it had Turkish and Israeli technology that was simply better than what Armenia had to draw on.” Armenia’s air defence systems relied on out-of-date technology, having been developed in the 1980s, and simply had no answer to Azerbaijan’s armed drones. The Weapons and Warfare site says Azerbaijan learned to work around Armenia’s clear advantages: “Before the war, on a tactical level the Armenian army was superior: it had better officers, more motivated soldiers, and a more agile leadership. In all previous wars with Azerbaijan, this proved to be decisive.”

But the drones allowed the Azeris to know exactly where Armenian forces were gathering and in what strengths. It was proof, if any more were needed, that advanced technology delivers massive military advantages to whichever side has it. Even so, as with all wars, misinformation played a part. Azerbaijan clamed that its drone armaments had destroyed more tanks than Armenia actually possessed.

LIFE WILL ALWAYS BE A GAS

Russia’s unprovoked assault on Ukraine has changed the energy market in Europe, almost certainly for good, or at least for a very long time. Natural gas futures in the EU traded at €98 per megawatt-hour, still falling on news of more supplies of liquid natural gas (LNG). Germany has agreed with Qatar to continue negotiations about long-term supplies, following a visit by Germany’s Economy Minister, Robert Habeck, to Qatar. Habeck has also been urging oil-rich Arab states not to profiteer from the Ukraine war by upping prices as they step into the gap left by Russia. Germany is also considering a hydrogen pipeline from Norway, while Gazprom seems to be making the most of its country’s aggression by ignoring it, continuing to supply gas to the EU because, it says, European consumers have asked it to. Yes, I know: that sounds most unlikely but it is what is being claimed.

When tiny marine organisms, animal and vegetable, were floating in the Ediacaran seas that had warmed, following a “snowball Earth” super-ice age, who would have thought they would come to be weapons in a vicious war? Or that trading in them would become a vital part of diplomacy? Eventually, they settled to the bottom of their sea, of course, became encased in silt and mud, and gradually heated in their aerobic tombs, began the long, long journey towards becoming natural gas. One day, we would trade it. One day we would find it hard to live without it. It’s a very good job the organisms floated, sank and were buried in many different places, because our modern world demands a lot of gas, all supplied by deceased microorganisams. We still have to rely on the flora and fauna of half a billion years ago to supply it, and that is likely to remain the case for a great many years into the future. Never write off microorganisms. They can be very useful, wherever and whenever on Earth they lived.