You may never have given much thought to organic chlorides – unless you’re interested in chemistry, of course – but you have almost certainly owned or used items in whose manufacture organic chlorides played a vital part. There are many uses, you will discover, to which organic chlorides can be put. They are essential in the manufacture of PVC, for instance, and in some pesticides. They are used in the manufacture of Teflon and in insulators. They used to be used to make chloroform, the anaesthetic of choice for moustache-twirling villains in old black-and-white movies, and from chloroform they have been turned into solvents until it was found that they were carcinogenic. Where you most definitely do not want organic chlorides is in crude oil, although very low levels of little more than one part per million is virtually unnoticeable and therefore tolerable. There are several ways of detecting the presence of organic chlorides, and oil producers really need to. Because one of the processes used in converting crude oil into its various valuable products, such as petroleum (gasoline), diesel and jet fuel, is called hydroheating, and if organic chlorides are present it can cause the formation of hydrochloric acid which can eat through pipelines and containers, seriously corrode and degrade valuable oil processing equipment and also, in a worst case, cause explosions. It also gives off the poisonous gas, chlorine.

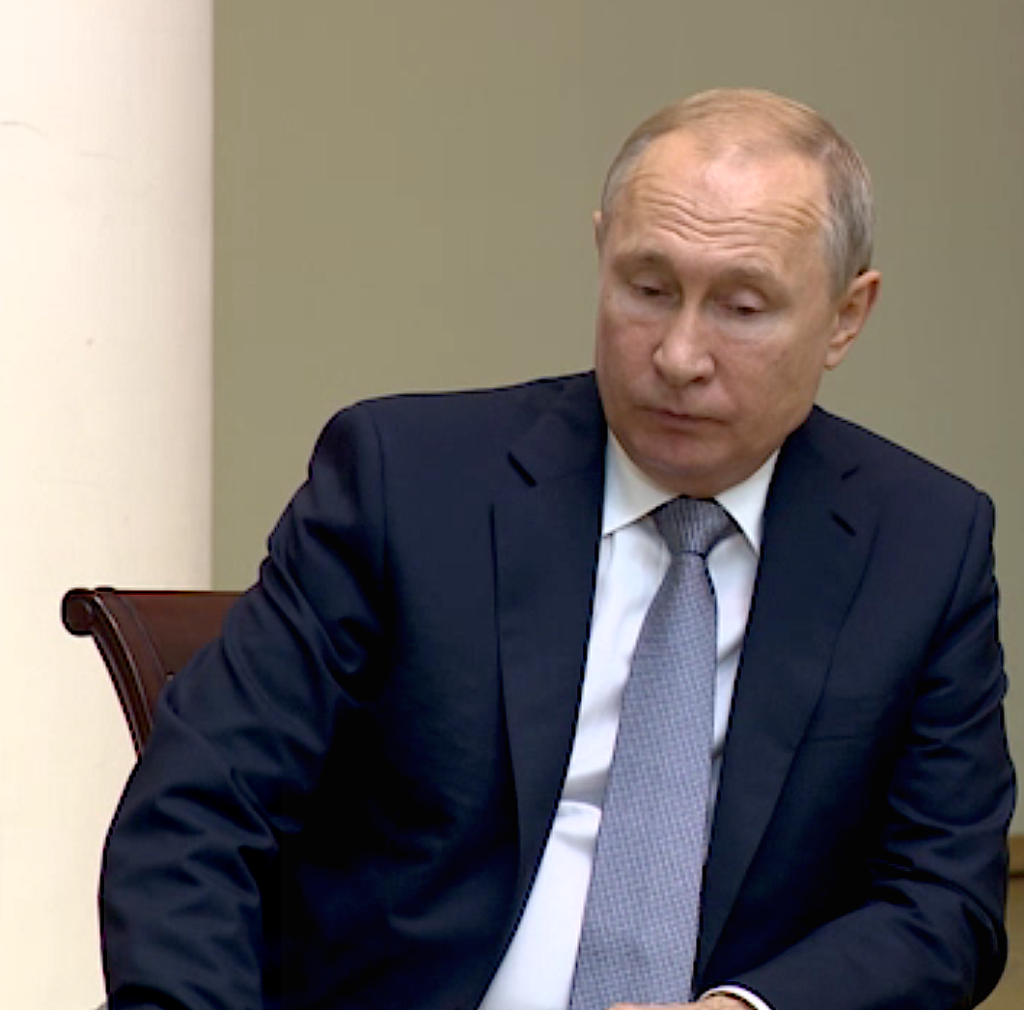

The presence of organic chlorides in Russian crude oil bound for export is currently causing something of a diplomatic explosion for Russia, President Vladimir Putin admitting it caused “very serious damage” economically and in public image terms. Moscow eased the regulations on just how much organic chloride could exist in crude oil in 2018 and the Eurasian Economic Union set the new upper limit in July this year at six parts per million. However, since the 2018 relaxation of the rules, organic chloride levels in oil coming from the Druzhba pipeline (somewhat ironically, Druzhba means friendship in Russian) have been shown to contain levels of organic chlorides that are well above accepted limits: up to one hundred times higher than permitted. The effect has been to shake faith in Russia’s oil industry while vast quantities of contaminated oil ended up lying fairly uselessly in storage facilities following a long journey to whichever country may have been obliged to store them. Russia has been engaged in a damage limitation exercise which includes trying to normalise the oil and make it useable. Russia is also offering to compensate financially any damage to plant and equipment caused by the polluted crude.

MOPPING UP THE MESS

Credit: Ust-Luga Port

The task has fallen to Transneft, the massive Russian conglomerate that runs a network of pipelines to Europe and China totalling some 69,000 kilometres in length. For them, it could have been worse: there are few signs so far of many European buyers rejecting future deals and looking elsewhere to buy their crude, although one Polish refiner, Grupa Lotos SA, is known to have been looking into ways to diversify its sources. That should ease the worries a little, despite the fact that Transneft must be anticipating some hefty claims for compensation. Certainly, the company was severely rattled as the Druzhba pipeline was forced to close (it has reopened since). Transneft spokesperson Igor Dyomin told Bloomberg: “It’s the first time we are facing such a situation,” adding that “it’s still too early to make any wrap-up analysis but we’ll definitely do it.” The out-turn cost of compensation is likely to be astronomical. Russia paid Kazakhstan $15 per barrel and Transneft estimates that it pumped more than 22-million barrels of contaminated oil overall. The company’s initial response when the alarm was raised, however, left much to be desired. Oil companies in Poland, Germany, Ukraine, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic received the warning from Belarus refinery company Belneftekhim but found they were unable to contact Transneft for several days, despite the company transporting some ten million barrels a day through Russia, four million of them for export.

While Moscow tries diplomatic means to mend its commercial ties with its unfortunate customers, the existence of organic chlorides in crude oil is not new or even entirely surprising, even if the quantity was. A number of cargoes from Texas have been rejected by European and Asian buyers over the last year because of poor quality. Although crude oil is mainly made up of hydrocarbons, there is also water present, along with chloride salts and other impurities. It normally undergoes a desalting process to get rid of the impurities, using more water to dissolve the salts before the cleaned petroleum is separated and piped off to the next part of the refinement process. The cleaning removes most chloride salts but not organic chlorides, which form what’s called a covalent bond with carbon, meaning that the atoms share some of their electrons and are therefore very tightly bound and much, much harder to get rid of. Unlike other chloride salts, they do not come from sea or ground water. They are more likely to have originated through cleaning products used on pipelines and in storage facilities, normally to clean oil wells to speed up the flow of crude. The pollution is thought to have entered the pipeline somewhere in central Russia where a number of private oil companies have access so that they can pump their own output into the pipe. That arrangement may change in the light of what happened, with Transneft probably taking over operational responsibility.

© Belarus Foreign Affairs

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

Things have been getting back to normal. Ust-Luga, in the oblast of Leningrad, has the largest and deepest port in the Baltic Sea and is used for the export by sea of Russian oil. In fact, it handles almost 90-million tonnes of cargo through its twelve terminals. It, too, was affected when it became known that the crude oil arriving along the Druzhba pipeline was contaminated. Several tankers sailed from Ust-Luga carrying oil that was sold to traders and major oil companies before the contamination was spotted. By August, however, Russia’s Energy Ministry put out a statement to the effect that organic chloride content there had been reduced to 2.6 parts-per-million, with the additional claim that it will not exceed 3.5 parts-per-million. The Energy Ministry’s statement then went on t say: “The expected oil quality in the port of Ust-Luga will be within the range of 1.6 to 3.5 parts-per-million for this indicator in the period from August 20 to 26, 2019. The Energy Ministry will continue oil quality monitoring in the port of Ust-Luga with the weekly update on the official website.” Oil being transported along the southern leg of the pipeline, through Ukraine to the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary was not affected.

How did the pollution occur? That has not yet been established, but Transneft and the Russian government say they suspect sabotage. Transneft claims the deliberate contamination was intended to “conceal multiple oil thefts” along the Samara-Unecha section. At a news briefing, Igor Dyomin, a spokesperson for Nikolay Tokarev, President of Transneft, told the media “the contamination was intentional.” Four people suspected of involvement in the pollution have been jailed by the Samara District Court in Samara City, including the general directors of the companies PetroNeft Aktiv and Nefteperevalka. “Currently, in respect of four suspects by the court at the request of the investigation, a preventive measure in the form of detention for two months was chosen,” according to a representative of the Investigation Committee in the Samara region, but adding that “two suspects are wanted.” Clearly, the investigation continues but the court named the four convicted so far. They are Svetlana Balabay, general director of Nefteperevalka LLC, Rustam Khusnutdinov, her deputy, Vladimir Zhogolev, general director of Petroneft Active, and Sergei Balandin, deputy head of Magistral LLC. The pollution was found at the privately-owned Samara Transneft-terminal, where several small-scale producers pump oil into the Transneft network, according to Dyomin. The first deputy director at the Samara Transneft-terminal told reporters that his company had sold the terminal in 2017 and he didn’t know who the current owners are. In a meeting with Putin, Tokarev reportedly said the oil had been deliberately contaminated by a private company, which he claimed “has deliberately injected oil that was not properly prepared.” It’s hard to see what the motive could have been.

Belarus’s Belneftekhim refinery company issued its warning about the quality of Russian oil on 19 April, saying that according to their research, the content of organic chloride compounds in the Druzhba oil pipeline exceeded the agreed limits by a factor of ten. The Russian Ministry of Energy later confirmed that Russian oil was contaminated with dichloroethane (C2H4Cl2). Used in the production of vinyl chloride, dichloroethane can cause severe renal failure if ingested by humans and other animals. Apart from the manufacture of vinyl chloride, dichloroethane is also used in solvents and for cleaning purposes, such as in refineries and storage facilities, which may rather explain its purely accidental presence in the Druzhba oil pipeline. Russia is also seeking to extradite Roman Ruzhechko, Chief Executive of a small oil transportation company, Samartransneft-Terminal, from Lithuania, where he has asked for political asylum but is being held on an Interpol warrant. Russia believes 40-year-old Ruzhechko was involved in the deliberate contamination of the Druzhba pipeline. A warrant has also been issued for the arrest of Roman Trushev, founder of the oil company Petroneft. Trushev told Deutsche Welle in April that Russia is “looking for scapegoats” and that the amount of oil delivered by his company was too small to cause so much damage. “I don’t understand what this has to do with me,” he said, whilst carefully withholding his location. Despite attempts to restore confidence after the April contamination scandal, Poland’s biggest refinery, PKN Orlen, told Reuters that the quality of Russian crude has been steadily declining for several years and continues to do so.

HARD TO IGNORE

The crisis certainly had an impact, although oil prices are subject to volatility, largely because of oil’s geopolitical importance and the places in which it is mainly found. The spot price for Brent crude, the international benchmark for oil prices, was at $59.41 (€52.04) in January 2019 but in May, after news of Russia’s pipeline contamination broke, it had soared to $71.13 (€63.38), peaking up more than 1.2% at $75.47 (€66.50). The oil market has started pricing in a risk premium, which helps to iron out the bumps a little, but it inevitably reacts to international events. Prices rose sharply after a drone attack this August by Yemen’s Houthi rebels on an oilfield in eastern Saudi Arabia, which caused a fire at a gas plant. There was also inevitable market reaction to the seizing of an Iranian oil tanker suspected of carrying fuel to Syria in the waters off Gibraltar and to Iran’s unsurprising retaliation in seizing a British-registered ship in the Gulf of Hormuz. More recently, as part of the on-going trade spat between Washington and Beijing, China has placed a tariff on American oil, while within the United States the Plains All American Pipeline (PAA) is imposing a surcharge on oil producers using the new Cactus II pipeline to offset the increased cost of steel resulting from tariffs imposed by the US. The surcharge is being challenged but it all makes oil more expensive. But oil prices overall tend to follow stock performances around the world, so prices recovered in the belief that governments globally would take action to counteract slow growth. However, the prospects for the oil market generally are beginning to look a little gloomy in the medium to long term, with the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cutting its forecast for 2019 by 40,000 barrels per day, down to 1.1-million barrels per day, as well as predicting there would be a slight surplus in the market in 2020. This isn’t helped by China’s plan to increase its own output by ten-million tonnes of paraxylene capacity by March 2020, which could oblige oil producers in Japan and South Korea to cut their production.

Concern over the pollution of oil in Russia makes a change from the more usual concern over pollution OF Russia BY oil. In Soviet times, Russia disregarded the environmental impact of its oil and gas extraction industries, but the inaccessibility of the regions where much of it was to be found tended to dissuade foreign investment following the collapse of Communism. However, with some 32% of the world’s natural gas deposits being in Russia, that is changing. Large deposits of oil and gas have recently been discovered in Sakhalin, an island off the Pacific coast of Siberia, and now some of the most ambitious projects in the history of the oil industry are under way there, with a consortium headed by Royal Dutch Shell building platforms, pipelines and processing plants in the area. It is already allegedly damaging the quality of water in Sakhalin’s rivers, a rich breeding ground for salmon and a vital food source for local people. The rapid development could be dangerous in other ways: according to Worldwatch Institute, the island lies in an area of strong seismic activity and nobody can be sure the platforms and pipelines could withstand a major eruption. That fear is unlikely to discourage Transneft from its intention to build what will be the world’s longest pipeline to transport oil from western and central Siberia to the Pacific coast. The pipeline will run through untouched taiga forests, severely endangering the extremely rare Amur leopard (only 35 are known to survive), as well as passing close to the Unesco World Heritage Site of Lake Baikal, which would be in breach of international law.

THERE’S POLLUTION AND POLLUTION…

All of this may well be of little interest to the handful of state-run monopolies that profit from Russia’s oil wealth. And it’s true to say that the world still needs oil and looks likely to do so far into the future. However green you are, you need oil. You will continue to need oil. “There is little reason to believe that once it does peak, that oil demand will fall sharply,” wrote Spencer Dale, BP’s Group chief economist, and Bassam Fattouh, Director of The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, in a report published on-line by BP, “The world is likely to demand large quantities of oil for many decades to come.” The report suggests a gradual change in oil markets to a state of over-abundance which is likely to affect prices over the next two to three decades. “More generally, it seems unlikely that oil prices will stabilise around a level in which many of the world’s major oil producing economies are running large and persistent fiscal deficits. As such, the average level of oil prices over the next few decades is likely to depend more on developments in the social cost of production across the major oil producing economies than on the physical cost of extraction.” The change in demand will depend on geographical and economic factors, with demand falling in advanced economies but still rising in developing countries. “Demand for oil in developed countries will revert to structural decline by 2020, wiping out about four million barrels per day by 2035,” according to Wood Mackenzie, the global energy, chemicals, renewables, metals and mining research and consultancy group, “In contrast, developing economies will increase their demand for oil by nearly 16 million barrels per day by 2035.” But as most analysts are quick to point out, the oil industry, being such a vital part of the global economy, has ridden out plenty of crises in the past.

Even so, a crisis such as the contamination of Russia’s principal oil pipeline, has inevitable consequences. “It will leave refiners like PKN Orlen, Total, Shell, BP and Rosneft scrambling for supply,” Phil Flynn, senior market analyst at the PRICE Futures Group in Chicago, told Deutsche Welle, “While Russia says the problem will be fixed quickly, the impact on consumers will last longer.” German refineries that rely on crude from the Druzhba pipeline had adequate stocks to cope in the short to medium term, meaning there was no need to tap into Germany’s strategic reserves. The same sang-froid is notable by its absence in Belarus. Belarusian refineries have been complaining for several years about the declining quality of Russian crude, although the sudden deterioration resulting from organic chloride pollution is something new. It was the Belarussian State Concern for Oil and Chemistry, Belneftekhim, that raised the alarm this time, but only after accusing Moscow for some time of dragging its feet over a worsening situation that it had pledged to rectify. About 25% of Russia’s oil output passes through Belarus and Belneftekhim claims the dirty oil has already cost it $100-million (€90-million) in losses. It deepens an ongoing dispute between Moscow and Minsk over Russian oil. Belarus has accused Russia of a high-handed attitude to its neighbour and of poor maintenance of its facilities. “If you need to repair the oil pipelines and oil pipelines that go through Belarus, suspend [the flows] and repair it,” Belarus President Aleksander Lukashenko said of Russia during a government meeting, according to Belarus’ BelTa new service. “They have become arrogant to such an extent that they begin to twist our arms.” Belarus has said it will start to look for alternative sources of crude oil by the end of this year, although that is unlikely to happen.

It’s been claimed that the polluted oil has damaged processing plant and equipment in Belarus. Flynn warned Deutsche Welle that the dispute could be a sign of things to come: “We know that Russia in the past has had many issues with former satellite states,” he said, “and they may use an incident like this to perhaps exploit the issue for larger political gain.” It’s well documented that Lukashenko and Putin do not like each other but both men inevitably try to wrest some benefit from any unexpected eventuality. As it is, Russia exports around 360,000 barrels of crude a day to Belarus and is easily the country’s largest supplier. Furthermore, it has been supplying the oil tax free at a cost of $5-billion to the Russian economy. Russia now plans to cancel its export duty for crude and oil products by 2025, when the Eurasian single energy market comes into effect, meaning boundary-free movement of oil.

The problem for Belarus is that it is a debtor nation and it is to Russia that it owes the money. According to the Ministry of Finance, as of June 1, Belarus’s foreign debt amounted to $7.82-billion (€7.06-billion), most of it – $7.55-billion (€6.82-billion) – to Russia, which means Russia is Belarus’s main creditor and Belarus is Russia’s biggest debtor. Minsk owes Moscow twice as much as Ukraine ($3.7-billion or €3.49-billion), Venezuela ($3.5-billion or € 3.16-billion) or Cuba ($3.2-billion or € 2.89-billion). It means in effect that every individual citizen of Belarus owes Moscow $794 (€717). This summer, for the first time in recent years, Moscow refused a request from Minsk for a loan of $630-million (€569-million) intended to refinance its current debt unless Belarus takes steps towards economic integration with Russia. Minsk has since borrowed $500-million (€451-million) from China. Belarus and Russia are already united in what’s called the Union State, but each of them retains its own sovereignty and international existence. They are both still fully responsible for their own internal affairs and external relations. Attitudes towards each other remain unsurprisingly prickly. Russia seems determined to regain control over as much of the territory of the old Soviet Union as it can, and Belarus’s Lukashenko is painfully aware of what happened to Crimea. The leaders of the Baltic states, Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia share his concern. For Putin, it looks like a sound move, arguably extending his power beyond the end of his presidency in 2024. It would also lock Belarus into Russia’s sphere of influence far into the future and prevent a possible escape.

SOUND ECONOMICS OR A LAND GRAB?

It all fits together with changes to Russia’s oil tax regime that would benefit the Russian economy but cause extensive economic damage elsewhere, especially for Belarus. In order to boost its revenue, over the period 2019–24 Russia will cut the export tax on oil (from which Belarus has been exempt) from 30% to zero and while raising the tax on oil production. Up until now, Belarus had been able to import Russian oil at below-market prices, either to refine it or else to sell it on, mainly to the European Union. In this way, Belarus has been able to undercut Russia in selling Russia’s own oil, all at the expense of the Russian taxpayer. The problem for Belarus is that ‘mineral products’, like crude oil and its refined products, account for around one-quarter of its exports. The Belarusian government says the cost to the country’s economy of the tax reform could be as high as $2-billion (€1.8-billion) by 2024, equivalent to 4% of the country’s GDP.

Altogether, seventeen countries owe Russia a total of $27-billion (€24.34-billion), with most of the country’s lending made through arms deals or unreported political loans, according to Russia’s RBC news website. It was reported in the Moscow Times that 25 countries and other legal entities owe Russia a total of $39.4-billion (€35.52-billion), including through government bonds. The estimate, which is for this year alone, comes from Russia’s Finance Ministry, although Russia classifies data from its export finance and loans programme as a state secret.

In diplomatic terms, the stakes have been raised by Russia’s appointment of Mikhail Babich as its ambassador in Minsk. The Belarusian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has accused Babich of making up false figures in his media interviews and of confusing an independent state with a federal district of Russia. Unsurprisingly, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has reacted furiously to the claim. Minsk was immediately wary when Babich, a former member of Russia’s security services, was appointed. He had been a presidential plenipotentiary to Russia’s Volga federal district before being appointed ambassador to Belarus last year, and had been Chechnya’s head of government during the second Chechen war. He was previously appointed as Russia’s ambassador to Ukraine in 2016, but Kiev rejected his appointment. Putin has also named the ambassador as his plenipotentiary, while there are those in Belarus who see Babich as a governor-general and part of the Russian threat. He certainly seems to be deliberately stirring up tensions between Minsk and Moscow, the very opposite of what most people would expect a diplomat to do. According to the Carnegie Moscow Centre, Babich made several fairly undiplomatic statements during a recent interview with Russia’s state-run news outlet RIA Novosti. His comments were what prompted the Belarusian Foreign Ministry’s complaints. Babich allegedly found six different ways to say that Russia was propping up Belarus economically (which, given its indebtedness may be at least partially true), and even accused President Lukashenko of using what he dismissed as “laughable examples” when making his own points. He also accused Lukashenko of attempting to whip up the support of his electorate by demonising Russia. The war of words has been heating up, with Moscow apparently determined to reduce its spending on Belarus, as well as replacing Belarusian imports with Russian products, from food items to trucks and ballistic missile transporters. Babich is not concerned about upsetting Minsk (which presumably reflects the views of Putin) because Lukashenko has nowhere else to go. His autocratic style of government would exclude him from any prospect of joining the European Union, and his country desperately needs the economic support of Moscow.

MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE OR SHOTGUN WEDDING?

Despite the angry exchanges, it seems inevitable that Belarus will merge with Russia, sooner rather than later; Lukashenko said as much in February after a long meeting with Putin. “The two of us could unite tomorrow, no problem,” Lukashenko said in a video shared by a Komsomolskaya Pravda tabloid Kremlin reporter on Twitter. “But are you – Russians and Belarussians – ready for it?” Lukashenko was quoted by Interfax as saying, “We’re ready to unite and consolidate our efforts, states and peoples as far as we’re ready.” Citing the interdependence of European Union member states as an example, Putin said that “fully independent states simply do not exist in the world,” according to The Moscow Times. Read the words of Babich or Lukashenko and it would seem that Belarus and Russia are on the brink of war. They are not, of course, as Putin’s more conciliatory statements confirm. “For us Belarus is the closest ally and a strategic partner,” he told a plenary session of the Forum of Regions of Belarus and Russia on 18 July, according to the Belarus news agency, BelTA (eng.belta.by). He went on to claim that relations are built on good neighbourliness and with regard to each other’s interests. “Our countries step up political and economic interaction within the framework of the Union State of Belarus and Russia, whose 20th anniversary is marked this year.”

The row over polluted oil has highlighted and drawn to the world’s attention the fractious friendship depicted so differently by the parties involved. But the problems of dealing with the contamination and the costs involved in solving the problem could point the way towards a merger that would suit Putin admirably. He has to stand down definitively as President of Russia in 2024, allowing him, some say, to stand as a candidate to become President of the Russian-Belarusian Union State. If the path towards that goal seems tricky, a little oil should lubricate it nicely. As long as it’s clean, of course. And he could always try silencing Lukashenko with chloroform (CHCl3).

Jim Gibbons