Members of the Royal Welsh Regiment as part of the NATO Enhanced Forward Presence in Estonia © NATO

Tucked away in the quiet, rolling hills and thick forests of northeastern Poland, the Suwałki Gap – also known as the Suwałki Corridor – isn’t a place that makes headlines often. But if you were to mention its name to military strategists or NATO planners, you’d likely see their expressions tighten. This unassuming strip of land, just 65 kilometers wide, is far more than a mere geographic oddity. It’s a vulnerable fault line in Europe’s security that could, if tensions boil over, become the spark for a much larger confrontation between Russia and the West. The region’s peaceful meadows and sleepy villages hide its grim nickname: NATO’s Achilles’ heel. And in an era where every move on the geopolitical chessboard matters, the Suwałki Gap isn’t just a footnote – it’s a potential battleground.

One century ago, the narrow stretch of land in western Poland known as Pomerania split Germany into two disconnected parts – the Weimar Republic to the west, and East Prussia, with its capital Königsberg, to the east. Sandwiched between them was the Free City of Danzig.

After the Second World War, Königsberg was taken over by the Soviet Union, and renamed Kaliningrad – after Mikhail Kalinin – a close ally of Lenin and Stalin. Once again, the city finds itself separated from its “motherland” – this time by the Suwalki Gap, named after a nearby Polish town.

During the Soviet era, the gap was irrelevant – Lithuania and Belarus were Soviet republics, and Poland was part of the Warsaw Pact. Even after the USSR collapsed in 1991, it remained a minor concern. But in today, following Vladimir Putin and Alexander Lukashenko’s moves towards a very deep political union, the Suwalki Gap could easily become a new flashpoint.

With the heavily militarised, Russian exclave of Kaliningrad to the west, and Moscow’s most loyal ally, Belarus to the east, the Suwalki Gap is the terrestrial lifeline connecting the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania to the rest of NATO. Its strategic importance is immense. If Russia were to seize this corridor, it would sever the Baltic states from their allies, isolate them geographically and deal a crippling, physical blow to NATO’s unity.

As Russia’s war of conquest in Ukraine grinds on, the spectre of Moscow’s ambitions looms larger, raising an urgent question: how can NATO defend this vulnerable choke point in an era of rapidly changing tactics and strategy? The Suwalki Gap’s geography is critical: stretching roughly 104 km from the Polish town of Suwalki, to the Lithuanian border, this corridor is a patchwork of flat farmland, thick woodlands and scattered lakes; a terrain that complicates large-scale military manoeuvres. Only two major roads and a single railway line traverse this narrow strip, creating a natural bottleneck that could easily be choked off by a determined adversary.

To the west, lies Kaliningrad, a heavily militarised Russian outpost bristling with over 15.000 troops, Iskander ballistic missiles and advanced air defences. To the east, Belarus serves as a staging ground for Russian forces, its proximity amplifying the threat of a pincer movement. The gap’s position makes it the only land bridge for NATO reinforcements to reach the Baltic states from Poland, turning it into a linchpin in the alliance’s eastern defences.

As early as 2015, the then commander of the US army in Europe, General “Ben” Hodges consistently highlighted the gap as a critical vulnerability and potential “ignition point” for conflict: ‘If Russia takes control over it, it will cut three members of the Alliance off from the supply and military assistance…the Suwalki Gap keeps top US generals in Europe awake at night’!

For Russia, seizing the gap would connect Kaliningrad to Belarus, creating a contiguous land corridor under Moscow’s control and encircling the Baltic states. It’s a move that aligns with Vladimir Putin’s obsession with reclaiming lost Soviet territories and asserting dominance over NATO’s eastern frontier. In any future conflict, the patchwork of farmland and muddy soil will limit the mobility of armoured units, while the dense forests and water barriers favour smaller, more agile forces. In practical terms, what is needed here, according to military analysts, are well-trained special operations forces, long-range missiles and drones to deliver precision strikes.

If Moscow decides to strike the Suwalki Gap, it can be expected to do so with overwhelming force. The question could be posed: would the combined forces of NATO be up to the challenge, and would the Suwalky Gap’s variable terrain give NATO a defensive edge? Well, it all depends, and the considerations here are more political than military.

Let’s take those questions in reverse order: first, the variable terrain. Broken terrain, corn fields, muddy soil, dense forests and water obstacles will generally favour smaller and more mobile forces, if they are deployed to provide defence in depth. Defence in depth is exactly as the name suggests; a layered, interconnected, overlapping and interdependent network of defensive positions.

While such a defence can be improvised, last minute efforts are – at best – dangerous and highly unreliable. Especially if this is attempted under sustained enemy fire.

However, this tactic takes considerable time, effort and consequently significant financial means. From a military point of view, defence in depth is always dependent on favourable terrain, secure lines of communication and supply, and accurate anticipation of enemy tactics. But above all, it demands sustained political will to implement.

| ARTICLE 5: NATO’S CREDIBILITY GAP

Effective defence of the Suwalki Gap requires more than just NATO’s paper commitments. Yes, Article 5 pledges collective defence – does it kick in automatically? In theory, yes. In practice, nothing is guaranteed.

Consider Ukraine: a nation fighting and bleeding under Russian aggression, yet NATO took nearly a decade to recognise the invasion as a direct threat to Europe.

Only now, after years of hesitation, are allies scrambling to ramp up weapons production and coordinate a response.

Here’s the dilemma: A decisive NATO deployment to the Suwalki Gap would probably trigger Moscow’s anger, risking rapid escalation. Yet without that resolve, the Alliance’s deterrent crumbles.

And then, there is another wild card: the United States. Washington, under the presidency of Donald Trump, remains an unpredictable factor. Would the US see reinforcing the Suwalki Gap as essential to European security, or dismiss it as an unnecessary provocation of Moscow? More crucially, would Congress approve the substancial funding required?

Even setting aside US involvement, critical questions remain about European NATO members. Do they have the strategic foresight and resolve to independently secure the Suwałki Gap? Are they prepared to invest in layered defences and station troops in the corridor and its adjacent staging areas?

Many military analysts remain sceptical. More pointedly, some experts even question whether NATO should prioritise the Suwałki Gap at all, with growing concerns that the whole enterprise is economically prohibitive and politically divisive.

Can the gap be defended? Militarily, yes – but in Western democracies, ultimate authority rests with the civilian government leaders. This brings us back to the fundamental question of political will: NATO faces a binary choice – either commit fully to defending this crucial corridor or accept the strategic consequences of inaction.

But there is an even more pressing concern: is NATO truly prepared for 21st-century warfare? The conflict in Ukraine has redrawn the battlefield, shifting from large-scale manoeuvres to drone-dominated, hyper-digital combat where small units decide engagements. This new era of warfare demands skills and systems that NATO has yet to prove it possesses at scale.

Anders Puck Nielsen is a military analyst and naval Captain at the Royal Danish Defence College, as well as a NATO adviser. He doesn’t mince his words when pointing out where the Western militaries have gone wrong: ‘NATO slept through the drone revolution. Russia is months behind Ukraine, but years ahead of the West. In a conflict, NATO would face heavy losses without urgent reforms. Existing doctrines assume lost territory can be retaken, but without drones dominating, that’s no longer guaranteed, especially for the Baltics’.

And on the diplomatic front, Valerii Zaluzhnyi, the former Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief and currently ambassador to the UK matches this bluntness with the precision of a drone strike, calling out strategic failures most military chiefs would only whisper about: ‘NATO’s warfare model is outdated. It’s not just about rearmament – we need a root-and-branch overhaul of tactics, training and budgets to match Ukraine’s high-tech warfare. If NATO abandoned tanks today, it would still take five years to catch up to Ukraine’s drone capabilities – and by then, the tech will have moved on’.

Electronic warfare and air defence have seen revolutionary change. Ground combat will likely never be the same. Consider this: when US forces last fought in Europe, the infantryman’s deadliest weapon was the venerable M1 Carbine. Today, it is the FPV or First-Person View drone – an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) streaming real-time video to an operator’s goggles, effectively turning every soldier into a precision air strike controller. On Ukraine’s battlefields, FPV drones account for 80% of Russian casualties. NATO now faces a sobering reality: the most lethal weapon system in modern combat didn’t exist four years ago. Should the alliance commit to defending European soil, it must prepare to wage a war unlike any in its doctrinal playbooks. To deny Russia the Suwałki Gap, NATO’s strategy must combine traditional deterrence with ruthless adaptation to 21st-century warfare’s brutal evolution.

The Alliance has already taken steps to bolster its presence in the region. It has deployed four multinational battle groups to the Baltic states and Poland since 2016, doubling troop numbers in eight eastern flank countries, and enhancing air and naval assets. Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO have further shifted the strategic calculus, turning the Baltic Sea to what some commentators call “a NATO lake”. Crucially, the Baltic Sea offers alternative reinforcement routes, but these measures – while significant – fall short of addressing the full scope of the threat.

Russia’s eagerness to connect Kaliningrad to its mainland via the gap is no great secret; Moscow has long viewed the exclave as a forward base to project power into Europe, and its militarisation – complete with nuclear armed missiles – underscores its intent.

The Baltic states, with their small populations and limited military resources are tantalising targets for a Kremlin that thrives on testing NATO’s resolve. To deter Russia, NATO must move beyond symbolic troop deployments and Cold War-era “tripwire” strategies that depend solely on Article 5’s threat of escalation. What’s needed now is a substantial, combat-ready forward presence with full logistical support, positioned in the Baltic states and Poland, to hold the line from the first hour of conflict and to reduce reliance on the Suwalki Gap as a lifeline.

SPEED IS CRITICAL

Russia’s war games simulation in 2016 suggested that it could overrun the capitals of the Baltic states in 36 to 60 hours, leaving NATO little time to respond.

The ongoing war in Ukraine casts a long shadow over the Suwalki Gap. Russia’s military has been battered with casualties reportedly reaching the 1 million mark, and vast quantities of equipment destroyed. Yet it remains a formidable threat.

Admiral Rob Bauer who served as the 33rd Chair of the NATO Military Committee from June 2021until January 2025 was the main military adviser to the NATO Secretary General and the North Atlantic Council. He constantly emphasised NATO’s shift back to collective defence since 2014: ‘There is a need for higher readiness and prepositioned forces in the eastern parts of the Alliance. This overarching strategy directly addresses the vulnerabilities of areas like the Suwalki Gap. NATO is on a rise in readiness, but there’s also work to be done to reach the desired force levels’.

A significant number of NATO military officials and European Union experts assess that the Russian forces in Ukraine are heavily depleted. But relying on forecasts always carries some risk, and current indicators suggest Russia will probably not strike the Suwalki Gap in the near term.

However, a premature cease fire in Ukraine would dramatically escalate the danger to this corridor. Should Putin secure a frozen conflict – retaining occupied territories, without achieving total victory – he may well shift focus and resources towards the Baltic states.

Such a ceasefire would allow Russia to rebuild its military, replenish depleted stocks and exploit NATO’s perceived complacency. Putin will almost certainly exploit NATO’s war fatigue to make a move.

With Ukraine no longer draining Moscow’s military resources, the Kremlin could mass forces in Belarus under the pretext of exercises – as it did during the 2021 “Zapad” drills which involved 200,000 Russian and Belarusian troops, 760 pieces of equipment and 15 naval vessels. Such deployments would position Russia for a potential strike against the Suwalki Gap.

The scenario is not hypothetical: Russia’s reliance on Belarus as a staging ground for its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, coupled with the Wagner Group’s presence there in 2023, shows Moscow’s readiness to use proxies and hybrid tactics to destabilise the region. A ceasefire in Ukraine could embolden Putin to test NATO’s eastern flank, gambling that a war-weary West would hesitate to respond decisively.

The Suwalki Gap – already a propaganda motif for Moscow and Minsk – would become the obvious target… A low-cost, high-impact move to fracture NATO’s unity and isolate the Baltic states.

The war in Ukraine has rewritten the rules of ground warfare, and NATO appears to be lagging behind. The proliferation of drones – cheap, lethal and ubiquitous – has transformed the modern battlefield. Precision strikes, real-time reconnaissance and the disruption of enemy communications were once the work of higher military echelons; now, these tasks are performed by ten-man rifle squads.

This wasn’t an evolution in ground warfare – it was a revolution. The war in Ukraine has brought epoch-making changes in tactics, weaponry, and the invisible domain of electronic warfare. Yet the question remains: is NATO – or even the United States – fully adapting to the realities of 21st-century warfare?

Ukraine and Russia have refined drone warfare through brutal trial by fire. NATO by contrast, lacks comparable, combat-tested expertise. For decades, NATO forces trained for counter insurgency in Iraq and Afghanistan – leaving them potentially ill-prepared for the high-intensity, drone-dominated battlefields of modern war that could prove extremely dangerous in the Suwalki Gap.

Russia could wage war without crossing borders with ground troops; it could deploy drone swarms to target NATO reinforcement columns, disrupt supply networks and create strategic chaos. Long-range artillery and Iskander missiles based in Kaliningrad, enhanced by sophisticated electronic warfare to jam NATO communications, would multiply the threat exponentially. NATO’s current, Cold War mindset, relying on static defences and relatively slow-moving reinforcements offers little to counter this hyper-mobile, asymmetric approach.

NATO must urgently revolutionise its combat doctrine – equipping frontline units with layered drone defences, while developing offensive swarm capabilities of its own. Operators in forward positions, down to the squad level require networked sensor systems to detect and neutralise drone threats within seconds. Without this transformation, NATO risks being outmanoeuvred in the Suwalki Gap’s tricky and confined terrain.

| EYE IN THE SKY

The European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI), a next-generation air defence system designed to counter missiles and drones could prove decisive in securing the Suwalki Gap. First proposed by German Chancellor, Olaf Scholz in 2022, he tied ESSI to Germany’s pledge to spend 2% of GDP on defence and modernise its military, to address NATO and the EU’s shortfall in air and missile defence systems.

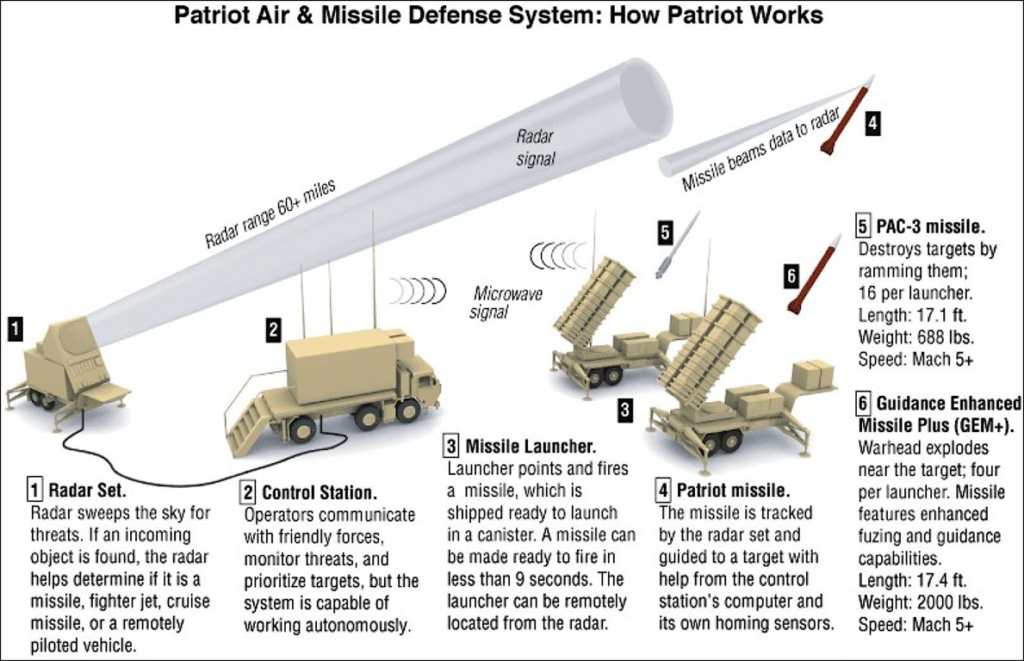

This ambitious programme aims to create a multi-layered defensive shield, combining:

- Short-range Skyranger-30 anti-aircraft systems

- Medium-range Iris-T SLM missiles

- Long-range Patriot-104 batteries

- Very long-range Arrow-3 hypersonic-capable missiles

Olaf Scholz framed ESSI as a response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, emphasising the need for integrated defence systems: ‘Europe must close its air defence gaps urgently. The Sky Shield Initiative is not just about procurement – it’s about collective security against missile threats from Russia, particularly from Kaliningrad’.

The ESSI operates separately from NATO since it includes the neutral countries, Austria and Switzerland. And many believe the real push for Greece and Turkey to join came after Donald Trump criticised NATO members not spending enough on defence.

However, France, Italy and Poland are noticeably missing – they’ve chosen not to join this defence project. So far, ESSI appears to be more of a political effort to quickly buy ready-made air defence systems and close gaps in Europe’s protection. But whether it actually works in practice still remains to be seen.

French President, Emmanuel Macron opposed ESSI for excluding the French-Italian SAMP/T system and advocated for a “European preference” in defence procurement: ‘We cannot outsource Europe’s security to non-European industries. ESSI’s reliance on US and Israeli systems undermines our strategic autonomy’.

As for Poland, while Prime Minister Donald Tusk expressed interest in joining ESSI in April 2024, then President Andrzej Duda and the conservative opposition dismissed it as “a German business project”, preferring to prioritise US-compatible systems like Patriot and AEGIS Ashore.

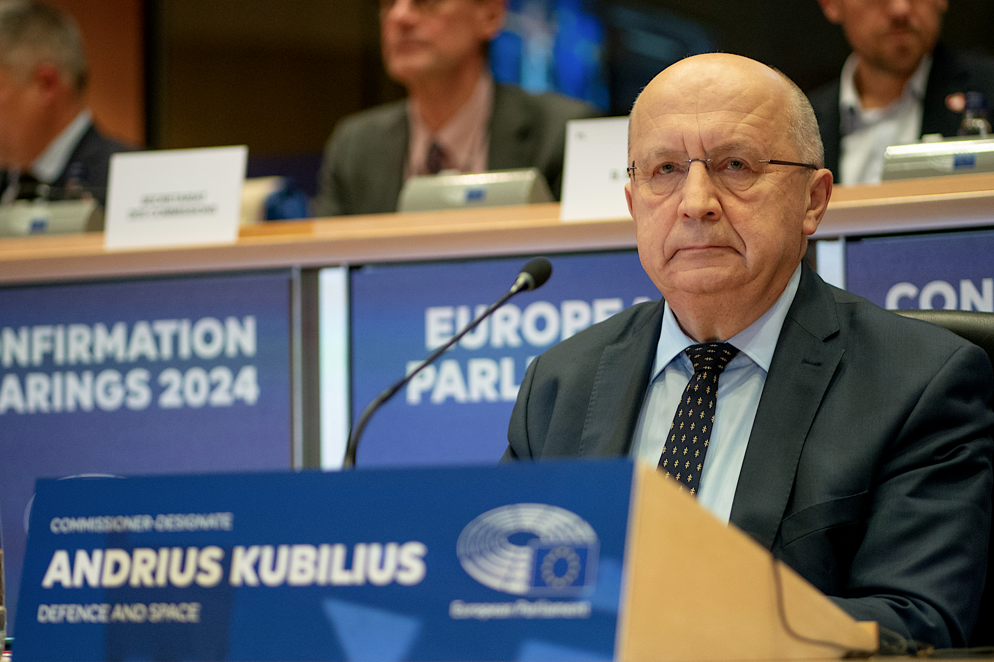

Meanwhile, Andris Kubilius, the EU’s Defence Commissioner linked ESSI to the European Defence Industrial Programme (EDIP), urging joint borrowing to bear the enormous cost and to accelerate capabilities: ‘ESSI is a cornerstone of the EU’s defence industrial strategy, but funding remains a challenge. A European sky shield alone could cost up to €500 billion’.

In this context, the European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen criticised Hungary for vetoing EU defence funds that could support efforts linked to the ESSI. She cited Budapest’s opposition to the €6 billion that was destined to Ukraine via the European Peace facility (EPF), the EU’s off-budget fund designed to strengthen the bloc’s defence and security role globally:

‘ESSI aligns with the EU’s Strategic Compass, but we need faster decision-making. Unanimity rules cannot block critical defence projects’.

| WAR OF NARRATIVES

But as both Russian and Ukrainian forces learnt it the hard way, 20th-century air defence systems are not entirely effective against modern FPV drones – their small radar cross-sections and low-altitude flight profiles evade traditional detection.

ESSI is essentially a shield against jet fighters, bombers, cruise and ballistic missiles, but not FPV drones. And that’s precisely where the danger lies. Sky Shield is not a panacea; it’s still in development, with full deployment still some time away. And its focus on air threats does little to address ground-based assaults or hybrid tactics. Russia is capable of exploiting this window of vulnerability and strike before the system becomes fully operational. What’s more, the Suwalki Gap’s narrow geography limits the effectiveness of large-scale manoeuvre elements.

In this terrain, it is hard-hitting, mobile and flexible forces that are needed to hold the line. Sky Shield must be paired with a robust and modern ground presence, as well as drone counter measures to truly safeguard this vital piece of terrain.

The Suwalki Gap is truly a test of NATO’s resolve and adaptability. Both military and civilian authorities within the EU are unanimous: to prevent Russia from seizing it, the Alliance must act decisively. It must bolster forward defences, preposition supplies and master the drone-driven warfare that defines modern conflict.

Meanwhile, Moscow keeps insisting that it has no strategic interests in this region.

In 2023, Russian Minister of Industry and Trade, Anton Alikhanov, who, at the time, was the governor of Kaliningrad Region declared in an interview with the RIA Novosti news agency: ‘The Suwalki Corridor is not interesting, no matter what anyone tells you. Even if the experts will say something about the fact that this is the most important area and it is necessary to take it under control. No need… Because there’s nothing but a two-lane highway winding through the woods. It is extremely inconvenient from the point of view of logistics – both conventional and military. Who needs this territory in terms of logistics and rapid transfer of troops or something else? No one!’

The Kremlin is also keen to point out that western media “keep fuelling the hype around the Suwalki Corridor”. They make reference to an article published by Politico in 2022, with the title: “The most dangerous place on Earth”. It noted that “Western military planners warn that if the Russian president ever decides to escalate the war in Ukraine to a kinetic confrontation with NATO, this area (the Suwalki Corridor) will probably be one of its first targets.”

However, according to Sergey Ermakov, an expert at the Russian Institute of Strategic Studies (RISS), the Suwalki Corridor has long attracted the attention of NATO military leaders, because it is one of the most vulnerable places for a supposedly, hypothetical Russian attack on NATO countries. Hence the plans for conducting exercises in this area. In an interview with RT, he declared: ‘This notorious myth of the Russian threat is being inflated by NATO members to maintain the solidity of their ranks and to extract more and more money for military spending. This is why such horror stories are drawn. The persistence of this myth is facilitated by the fact that from the point of view of military geography, this place is really considered quite vulnerable to the NATO military.’

| TIME BOUGHT IN BLOOD

Be that as it may, the war in Ukraine has allowed the West to buy time. But that time has come at a horrific cost – paid in Ukrainian and Russian blood. Every day of fighting weakens Russia’s immediate military strength, grinding down its forces in a war of attrition. Yet if the West pushes for a premature ceasefire now, that hard-fought advantage could vanish overnight. Moscow would seize the chance to regroup, rearm, and return deadlier than before.

NATO’s forces have not been tested in this new era of warfare – not like Ukraine has. The lessons being learned on the bloody battlefields of Bakhmut and Avdiivka cannot be ignored. NATO must absorb them, adapt, and close the experience gap before it’s too late.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. This isn’t just about Ukraine. Should Russia breach the Suwalki Gap – whether through relentless pressure or Western indecision – and establish a land bridge between Kaliningrad and Belarus, the strategic consequences would be very grave. The Baltic states would be isolated, NATO’s credibility shattered, and Vladimir Putin would see proof that brute force works. Decades of deterrence, carefully built since the Cold War, would unravel in an instant.

This isn’t some distant, theoretical threat. The Suwalki Gap is real – a quiet stretch of land, just 65 kilometres wide, dotted with forests and farmland. But it’s also the front line of Europe’s future. If NATO isn’t ready to defend it, the next war won’t be fought on Ukraine’s soil. It’ll be fought on ours. The clock is ticking, and time, as Ukraine has shown us, is never free.

hossein.sadre@europe-diplomatic.eu