© Kremlin.ru

One of my clearest memories of Kyiv is a visit to Maidan Square, bustling with people around the large Monument to Kyi, Schek and Khoryv, the legendary founders of Kyiv, that stands at the foot of the even larger and very tall monument to Ukrainian independence. Strictly speaking, I should refer to the place by its correct name: Maidan Nezalezhnosti, which means, unsurprisingly, Independence Square. I was filming (as a video journalist it’s my job) and quite a few people gave me hostile, suspicious looks. They clearly didn’t trust a man with a camera. Given Ukraine’s history, it’s hardly surprising. Neither is it surprising that many Ukrainians have little fondness for Russia, even if a sizeable proportion recognize their ethnic unity. During the period 1932-1933, the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin killed a great many Ukrainians in what is called the Holodomor, a term derived from the Ukrainian words for hunger (holod) and extermination (mor), but which is often translated as “death by hunger”.

It was a deliberate attempt to starve the entire population to death. I have spoken with Ukrainians whose parents and grandparents had suffered that way; they told me what it had been like. They were unable to buy food, Russian troops and party officials had removed it from the shops as well as from their cupboards, sometimes ripping up floorboards and firing guns up the chimney, I was told, in case any food may have been hidden there.

They also took away food bought for family pets and even the pets themselves, in case the peasants ate them. The intruders, some of them soldiers, also forced their way into homes where skeletally-thin families, including children, were in the middle of eating what little they could find, often by foraging.

They would take the food outside, pour it on the ground and stamp on it to ensure it was inedible, before driving away. They didn’t want the food themselves but wanted to ensure the Ukrainians had nothing to eat.

Any foodstuffs found by these murderous teams were confiscated, often destroyed in front of the victims, while the population had only limited rights to move from place to place. They certainly weren’t allowed to cross borders into countries where food was available.

It was an incredibly brutal act and barely understandable, except as an example of Stalin’s madness, megalomania and lack of sound judgement, although there was a kind of icy cold logic to it. He had decided to collectivise farming because collectivisation was part of Communism (although Karl Marx would not, I think, have approved of mass murder to achieve it). To reach his goal, Stalin sent teams of party agitators into the Ukrainian countryside. The Ukrainians had resisted the collectivisation plan, so peasants were forced to relinquish their land and their personal property. Wealthy peasants, known as kulaks, and those resisting the collectivisation were deported. Some were shot. It led to desperate food shortages and even armed rebellion in some parts of the country, albeit short-lived and unsuccessful.

Stalin admitted to his close confidantes that he was worried that he “could lose Ukraine”, but the Politburo decided to go even further, putting towns and villages on blacklists which meant no food of any sort was allowed to reach them. Stalin could have ameliorated the effect by setting norms for grain deliveries to the state.

He could have reduced grain exports or replaced confiscations with a range of taxes. In his excellent but terrifying book “Stalin – a new biography of a dictator”, writer Oleg V. Khlevniuk wrote: “Documents discovered in recent years paint a horrific picture. All food supplies were taken away from the starving peasants – not only grain, but also vegetables, meat, and dairy products. Teams of marauders, made up of local officials and activists from the cities, hunted down hidden supplies – so-called yamas (holes in the ground) – where peasants, in accordance with age-old tradition, kept grain as a sort of insurance against famine.” Khlevniuk says peasants were tortured to reveal where their yamas were along with any other food sources. “They were beaten,” he wrote, “forced out into sub-freezing temperatures without clothing, arrested, or exiled to Siberia.”

The reason for this extreme cruelty was that Stalin’s collectivisation policy was causing starvation in other parts of the USSR as well and the Politburo was determined to discourage further disobedience. Between 1931 and 1934, at least 5 to 7 million USSR citizens died of hunger or became permanently disabled through starvation, some 3.9 million (a low estimate) of them Ukrainian. Of course, the matter was hushed up by the Soviet authorities and was only revealed to public awareness in 1986, just after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. That, too, had been hushed up by Russia. Back in 2020, a sculpture commemorating the horrendous man-made famine, called “Bitter Memory of Childhood” and featuring a clearly unhappy and painfully thin little girl, was vandalised at Kyiv’s National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide. The culprits pulled the statue down but failed to carry it away, probably because it was too heavy. The police are investigating, but there are obvious suspicions of a Russian involvement, of at least the informal variety. Ukrainians are keen to remember the Holodomor, in order to honour its many victims (often family members); the Russians would rather it was forgotten, although wrecking commemorative sculptures seems an unlikely way to achieve that. It may have been carried out by a group of pro-Russian thugs, although witnesses claim the attack was well organised, with the vandals posing as drunken party-goers. Perhaps they really were just drunken party-goers. The sculpture is being repaired.

The other things I recall about Maidan Square were what looked to be jolly hen parties of young women, singing and dancing in the street, sometimes with nearby boys snapping pictures, as well as groups eating take-out lunches by the founders’ sculpture. There was also a veritable army of mainly youngsters shaking collecting tins at strangers like me. They said it was to help fund Ukraine’s resistance to the pro-Russian rebels in Ukraine’s Donbass region, but they could have been collecting for the rebels instead, for all I could tell. That memory is a reminder of another good reason for many Ukrainians to hate Russia. Whatever the rebels may think they’re achieving, Putin has succeeded in doing exactly what Stalin feared: losing Ukraine. What’s more, the clumsy ineptitude of Putin’s allies in Donbass ended up costing a lot of innocent lives when scheduled Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur was shot down in July 2014, using a Russian Buk missile that had been fired by rebels who mistook it for a Ukrainian military jet. All 283 passengers and 15 crew were killed. Russia is still denying involvement but only they operate this radar-guided anti-aircraft missile system, parts of which were found at the scene. Putin is somewhat like a very dangerous version of the naughtiest boy in the school who, when caught doing something awful, invariably says “it wasn’t me” and accuses the teachers of picking on him.

HISTORY REPEATING ITSELF

It’s strange how the Second World War continues to cast a shadow over the politics of today. Putin’s professed hatred of Nazis is the justification he uses for many of his actions. Take, for instance, his attitude to Ukraine and then compare and contrast it with what he did in Syria. Don’t look for consistency; there is none. On the one hand, he believes that the rule of law insists on a leader – any leader, regardless of how vicious and corrupt – being kept in power, with many civilians having to die to ensure that happens. Then he dismisses the government of Ukraine as ‘fascist’ to justify his actions to seize at least part of the country. When Ukraine organised a more consistent counter-offensive against the rebels and their Russian allies in 2014, Putin switched to a more ‘hybrid’ approach: a simple invasion of Donbass.

He sent a convoy of troops carrying some food supplies for the rebels, which he called ‘a humanitarian convoy’, though one has to wonder about his definition of ‘humanitarian’, when the vehicles were carrying troops and weapons. Putin claimed that Russia had been “forced” to send them in order to “defend the Russian-speaking population”. Ukraine and most Western nations regard it as the invasion of a sovereign nation’s territory.

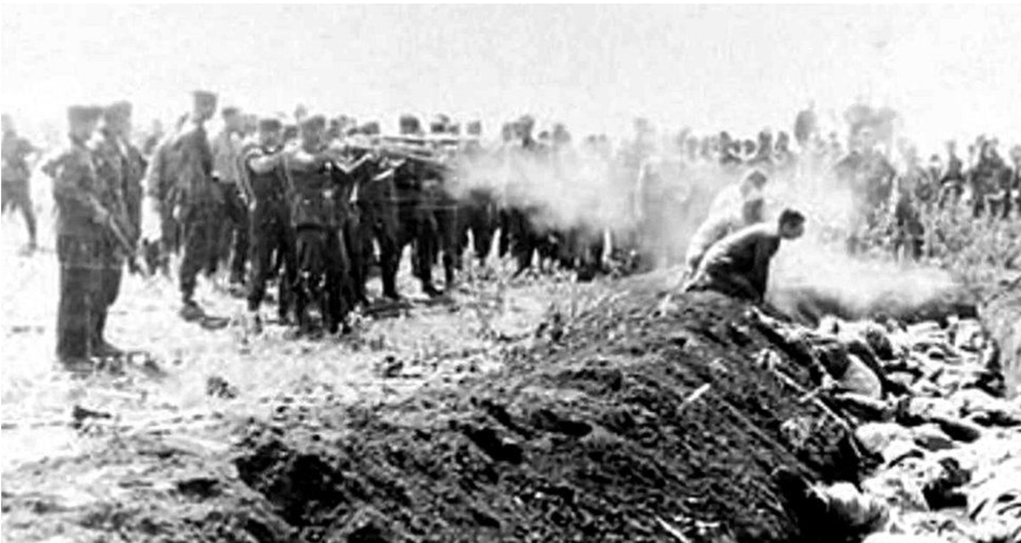

Russia’s seizure by force of Crimea is the first example of one country changing international boundaries through invasion since World War II. Some residents of Crimea initially welcomed the Russians as “liberators”, just as some Ukrainians had welcomed the Nazis in 1941 for seeming to remove the USSR’s yoke, although those first impressions proved woefully wrong. The Nazis did not believe in Ukrainian independence, quickly attaching Galicia to Poland (not that the Poles had much say in it, of course), giving Bukovina to Romania and putting Romania in charge of Transnistria. The Nazis then started to implement their racial policies, killing some 1.5-million Ukrainian Jews between 1941 and 1944, with many of the deaths occurring in just two days. The murderous incident is reported on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“On September 29-30 1941, SS and German police units and their auxiliaries, under guidance of members of Einsatzgruppe C, murdered a large portion of the Jewish population of Kiev at Babi Yar, a ravine northwest of the city” it reports. “As the victims moved into the ravine, Einsatzgruppen detachments from Sonderkommando 4a under SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel shot them in small groups.” Standartenführer was a Nazi party rank, equivalent to a captain in traditional military circles outside the fantasist world of the Third Reich.

We have to recall that many of the top Nazis believed in the occult. Many of their stranger ideas are detailed in the book ‘Hitler’s Monsters’, by Eric Kurlander. He writes that Hitler and Goebbels believed, among other things, that there had once been a ‘World Empire of Atlantis’ that had been destroyed by moons falling to Earth. Nazi scientists were instructed to check for ‘death rays’ at party headquarters which they feared could be being aimed at them, and to track enemy submarines by using a chart of the Atlantic and a metal cube on a string (I used to know someone who chose their lottery numbers that way; they never won). SS officers studied runes and believed themselves to be connected to a Hindu warrior caste. Partly, it was intended to undermine the theories of relativity, which the Nazis saw as ‘Jewish’ (perhaps it’s just as well: if they’d given any credibility to Albert Einstein they may have developed a nuclear weapon, but the antisemitism prevented that). Some even travelled to Tibet during the war to look for a lost Aryan tribe. They believed in astrology, too. The thought of people like Hitler, Martin Borman, Adolf Eichmann, Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler dancing in a fairy ring in the middle of some gloomy forest would be too horrible for even the Brothers Grimm to have dreamed up.

Meanwhile, back in Ukraine, according to a report to headquarters in Kyiv by the Einsatzgruppe, a paramilitary death squad, 33,771 Jews were massacred in this first two-day period. After that, most Ukrainians no longer regarded the Nazis as ‘liberators’. More than 2-million Ukrainians were taken to Germany as slave labourers, although the Germans tagged them “eastern workers”. The Germans only started to retreat from Ukraine after the bloodbath at the Battle of Stalingrad saw the Red Army retaking the territories seized by Nazi Germany. Altogether, up to 7-million Ukrainians died, while more than 700 of Ukraine’s towns and cities were destroyed and 10-million people were left homeless. So, Ukraine has suffered over the decades, from the policies of Stalin and then from the ambitions of Adolf Hitler. They have a right to look to look somewhat askance at an ambitious neighbour, who seems to be hungry for territory, especially one who has stationed 100,000 troops close to its borders.

PULLING STRINGS, CAREFULLY

It’s very easy with the benefit of hindsight to criticise and condemn those who failed to stand up to bullying by the invaders, but if the people had families and children to keep alive, it may have been a case of what in English is called ‘Hobson’s choice’: no choice at all. That’s why it’s often best left to powerful outsiders to right wrongs and defend the weak. As far as the EU is concerned, the power that can be exerted is economic. In July, the Council of the EU agreed to extend by a further six months, until the end of January 2022, the sanctions already imposed on Russian persons and entities in response to the deliberate destabilisation of Ukraine. They have been in place since July 2014, when Russia illegally annexed Crimea. According to the Council, the sanctions restrict “access to EU primary and secondary capital markets for some Russian banks and companies, as well as prohibiting certain forms of financial assistance and brokering towards Russian financial institutions” the Council explains. “The sanctions also prohibit the direct or indirect import, export or transfer of all defence-related material and establish a ban on goods for dual-use or direct military us, or military-end users in Russia.” In addition, the EU has put in place diplomatic measures, such as asset freezes and travel restrictions, as well as specific restrictions on economic relations with Crimea and the city of Sevastopol. Putin and his head of foreign policy, Sergey Lavrov, apparently dislike the EU and never miss an opportunity to denigrate it, as Lavrov very demonstrated when the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Policy, Josep Borrell, visited Moscow in February 2021. His treatment by Lavrov was, to put it mildly, a surprising display of bad manners that suggest disinterest on Russia’s part in normal diplomatic relations.

Moscow had announced a pull-back of its forces in April, but they seem to be still there. The head of Ukraine’s state security service, Ivan Bakanov, said he agrees with comments made by the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who has accused Russia of failing to withdraw its military hardware as promised.

There has been an upsurge in fighting in the disputed eastern part of the country around Donetsk and Luhansk, which may explain the more recent build-up of Russian forces. Moscow has also had its forces engaged in military exercises in the Black Sea area near Crimea.

The build-up has drawn criticism from Borrell as well as from NATO and from Washington, who said it was the biggest troop build-up since the seizure of Crimea. Moscow said it was a training exercise prompted by NATO activity in the area. Certainly, there is little agreement between Russia and NATO; the days of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, which Russia joined in 1991, are long gone. It’s hard to believe now that Russia joined the Partnership for Peace programme in 1994 and actually deployed Russian peacekeepers in support of NATO-led peace support operations in the Western Balkans in the late 1990s.

There was even a NATO-Russia Council (NRC) created in 2002, but Russia’s action in Georgia in 2008, which NATO described as “disproportionate” put an end to that. NATO still calls on Russia to reverse its recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states, but nobody seriously expects that to happen. All practical civilian and military cooperation under the NRC was suspended in April 2014 in response to Russia’s actions in Ukraine, especially its illegal annexation of Crimea. In fact, most countries seem to favour restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity to the way it was prior to Russia’s military invasion.

REALITY v. FANTASY

The invasion itself seems to have been planned some time beforehand, according to Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In fact, Russia doesn’t deny that but puts a gloss on it by issuing a medal to those taking part in what Moscow calls ‘the return of Crimea’. It was the day after the invasion that Ukraine’s pro-Russian president of the time, Viktor Yanukovych, fled Kyiv.

Few were sorry to see him go. It pays to take a look at Russia’s claim that they were getting back what belonged to them anyway. Russia, or at least its Tsarist Empire, annexed Crimea after defeating the Ottoman army at the Battle of Kozludzha during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774. It then stayed Russian until 1954, when it was transferred from the Russian Soviet Federation of Socialist Republics to its Ukrainian equivalent. The transfer had been approved by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Why was this generous transfer of power approved? Well, it’s hard to be sure, but it’s been claimed that it was “a noble act on the part of the Russian people” to mark the 300th anniversary of the reunification of Ukraine with Russia, related to the Treaty of Pereyaslav, signed in 1654 by representatives of the “Ukrainian Cossack Hetmanate and Tsar Aleksei the First of Muscovy to evince” – and I quote – “the boundless trust and love the Russian people feel toward the Ukrainian people”. Another part of the deal mentions the “strong links between the peoples of Russia and Ukraine” but it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. The Turkic-speaking Taters had lived in Crimea for centuries and could be said to be its most long-standing native population, but in May 1944 Stalin had them deported en masse to inhospitable sites in Central Asia, where they were forced to remain for more than four decades, prevented from returning home. Crimea was not their absolutely original home, either. The Tatar Confederation was incorporated into the Mongol Empire by Genghis Khan when he unified the Steppe tribes.

Today’s Russo-Ukrainian tension seems to be based on the uniquely Russian concept of “reflexive control”. We have little experience of it in the West but it has been a recognised weapon in Russia’s armoury for very many years. The Russians call it maskirovka, described on the website of the Georgetown Security Studies Review as an old Soviet notion in which one “conveys to an opponent specifically prepared information to incline him/her to voluntarily make the predetermined decision desired by the initiator of the action”. It could be described as “strategic diplomatic lying”, something at which today’s Kremlin excels. It has been taught at Russian military academies for very many years and seems to rely on the fact that people generally believe what they’d like to be true, rather than what actually is. It encourages self-deception to the advantage of the perpetrators over the people doing the believing. It’s very much one with Russia’s use of electronic communications to spread disinformation and pro-Russian propaganda. It worked, too; why else would an astonishing 53% of Republican voters still claim that Donald Trump won the last election but was cheated out of it by fraud. During a TV interview earlier this year, American (and Republican) businessman Mike Lindell tried to put over a baseless conspiracy theory, blaming a voting machine company for fraud in the 2020 presidential election. Roughly a quarter of American voters seem to believe that Joe Biden “stole” the election, without really being able to explain how, or at least trying to explain a variety of possible (but false) methods.

It was nonsense, of course (bringing to mind the Nazi hierarchy’s belief in the supernatural and their pre-ordained natural place in history) and the interview was interrupted by the newsreader pointing out that the network accepted the official election outcome, although that didn’t cause Lindell to shut up. Remember the Republican extremists’ attack on the Capitol in January? Only 29% of Republicans think Trump was in any way to blame for that and despite the presence of known Trump supporters, a surprisingly large number think it was really staged by left-wing activists to make Trump look bad. Putin must be laughing his socks off; who needs normal diplomacy if you can undermine your supposed enemy with palpable, almost laughable falsehoods? QAnon supporting extremist Jake Angeli’s strange outfit of fur hat, buffalo horns and a spear would have been quickly recognised by the likes of Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler as belonging to a kindred spirit, and possibly by readers of the Brothers Grimm (what exactly is the seemingly inevitable link between the far political right and a belief in the occult? There could be a doctoral thesis in there for somebody). Interestingly, while seemingly few Republicans think Trump was involved in the Washington attack, Angeli himself said he was responding to a call from Trump for all ‘patriots’ to be there. It’s not sure if he also believes the ludicrous claim that Russia did not invade Crimea and that its annexation was achieved by “volunteers”.

DRINK, ANYONE?

Certainly, from Russia’s perspective, the war over Crimea isn’t over. For ordinary citizens of Crimea, reality is uncomfortable, to say the least.

Food prices have soared and now there is a shortage of water, although June’s cyclone, which led to torrential rain and flooding, has helped to ease the pressure. In an ironic twist, Russia has accused Ukraine of “genocide” for damming the Soviet-era North Crimean Canal, which had provided 85% of Crimea’s water. Our distant ancestors were better at finding potable water than we are today, it seems. In an article about our dependence on water in the July 2021 edition of Scientific American, Asher Y. Rosinger, a human biologist at Pennsylvania State University, writes: “Without enough water, our physical and cognitive functions decline. Without any, we die within a matter of days. In this way, humans are more dependent on water than many other mammals are.” Rosinger’s article explains how access to water was pivotal in human development. Between about three million and two million years ago, the climate in Africa, where hominins (members of the human family) first evolved, became drier. During this interval, the early hominin genus Australopithicus gave way to our own genus, Homo.” Rosinger writes that the taller, slimmer build with a greater surface area reduced our ancestors’ exposure to solar radiation while allowing more exposure to wind. Water made us what we are. Putin had promised Crimeans “a better life” under his control, but as with previous invaders, many of the promises have yet to be fulfilled.

Reflexive control really works. There is further irony, too: Russia, which has laws to prevent the judgements of the European Court of Human Rights from being acted upon, has now filed a lawsuit in this court that it abhors and ignores, accusing Ukraine of “flagrant violations”.

Meanwhile, the governor of Crimea has launched a separate action claiming more than a trillion roubles in compensation and claiming that the blockade is an “act of state terrorism and ecoside”.

BIG DAY FOR LAWYERS

Needless to say, Ukraine has brought its own action against Russia, but as Moscow has made it a legal requirement to ignore the Court’s judgements, it’s hard to see anything emerging from all these cases except a financial bonus for quite a few lawyers. Russia has said there will be no war but has deployed large numbers of troops to the area, where they’ve dug trenches just a few hundreds of metres from those of the Ukrainians. As a matter of interests, some Crimean Taters, still angry with Russia over the mass deportations all those years ago, have set up camp to guard the dams on that canal. Moscow has accused Ukraine of “hysterical statements” intended to incite hatred. When there is clearly so much hatred there already, what would be the point? Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister, Oleksii Reznikov, has said that Kyiv would be willing to provide Crimea with humanitarian aid, including drinking water (it provides it already to the eastern territories run by pro-Russian rebels) but there has been no such request. In any case, Reznikov points out, as the occupying force, Russia is responsible under the terms of the Geneva Convention for making sure the people living in the territory have access to drinking water and adequate food.

The whole area would appear to be in a state of fear and also in a frightful mess as Russia and Ukraine argue over geography, or at least geopolitics. The way in which Stalin dealt with Ukraine in the early years of the war, as reported in Khlevniuk’s book, begins to seem oddly familiar. “The Soviet absorption of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus,” he tells us, “was not a joyous reunion of divided nations. For the first year and a half of their sovietization, the new territories underwent the same violent social engineering that the USSR had been experiencing for decades. The goal was to force them into the Soviet mold: do away with the capitalist economic system, inculcate a new ideology, and destroy any real or imagined hotbeds of dissent against the regime.” Ok, we can forget the part about destroying capitalism, but taking military action against any resistance seems to remain an element of Russian policy. Even so, Putin’s friends and allies are sure there will be no incursion in Ukraine. “He’s not going into Ukraine, OK, just so you understand,” Donald Trump assured viewers of a 2016 interview on ABC television in America. “He’s not going to go into Ukraine, all right? You can mark it down. You can put it down. You can take it anywhere you want.” It would be interesting to know (a) how he gained this knowledge (b) why he felt obliged to share it and (c) why he believed Putin. Trump blamed the conflict between Russia and Ukraine on his predecessor, Barrack Obama.

So you can believe Trump’s assurances or you can continue to worry that the Kremlin will never willingly accept that Crimea and Donbass are parts of Ukraine and not Russia. In any case, there seems very little sign of the sentiments that led to Crimea being transferred into Ukraine’s care by Nikita Kruschev back in 1954. Does anyone still believe in “the boundless trust and love the Russian people feel toward the Ukrainian people”?