© Edm

Agreements and alliances within the European Union (and elsewhere) about how best to obtain clean energy tend to be somewhat unstable. But there again, the atoms of uranium 235 (U-235) upon which the whole business depends are, by their nature, highly unstable. They have to be, or it would not be possible to produce nuclear power. Within the nucleus of each uranium-235 (U-235) atom are 92 protons and 143 neutrons (which are what go to make up the 235 total). The arrangement of these particles in uranium-235 is so unstable, however, that the nucleus can disintegrate if it is excited by an outside source. To create nuclear energy, it is necessary to excite the U-235 atom, and when its nucleus absorbs an extra neutron, it turns into the very unstable atom, Uranium-236, and quickly breaks into two parts. That is why it’s called nuclear fission.

Each time a U-235 nucleus splits, it releases two or three more neutrons, which can then go off and split more, thus creating a chain reaction. The splitting of an atom releases heat and gamma radiation, which is a form of radiation made up of high-energy photons. The process generates enough heat to boil water and produce steam, just as a coal-burning furnace does. The steam then drives a turbine fan that generates electricity. That part of the process would be familiar, I imagine, to people in the late 19th century. Not surprisingly, many people are wary of nuclear power because they’re afraid of nuclear radiation escaping and the fact that a similar atom-splitting technique with U-235 atoms is what powers a bomb.

Bombs are rather different, however, although in both cases, scientists must first enrich a uranium sample so that it contains up to 3 percent more U-235 than normal, which is sufficient for nuclear power plants to operate. If you’re creating a bomb, however, you’ll need weapons-grade uranium, which is composed of at least 90 percent U-235. In case you’re wondering how to enrich your uranium sample. it involves using a centrifuge after the uranium has been used to create a gas. The centrifuge separates the U-235 atoms from the U-238 atoms that will also be present. It takes several repeats of this operation because to begin with the increase in U-235 is quite modest. However, to get weapons-grade uranium is not only more difficult but also much more expensive. That is why so few countries actually possess the things. Slaughtering millions indiscriminately is a costly business.

However, despite fears over possible meltdowns, such as at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi, such events are extremely rare and are inevitably down to human error. Nuclear plants cannot explode like atom bombs, of course, but the generation of excessive runaway heat can melt the core. This can happen (although mercifully rarely) when the coolant source to the fuel rods fails and they overheat. This is what happened at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in March 2011. In that case, a powerful earthquake damaged the generators that powered the plant’s water coolant pumps. As a result, some of the reactors at Fukushima Daiichi got very hot and started to split the water into hydrogen and oxygen. At that point the hydrogen exploded, breaching the secondary containment walls around some of the reactors. Then another explosion caused catastrophic damage to the main containment structure. The remaining nuclear waste remains highly radioactive for hundreds or even thousands of years. At Chernobyl, Russian authorities poured hundreds of tonnes of water onto the reactor core to cool it, followed by boron, clay, dolomite, lead, and sand to try to stop the radioactive particles from rising into the atmosphere, finally encasing the stricken plant in a kind of concrete overcoat, sometimes referred to as a ‘sarcophagus’, a somewhat ominous name for something doing a very ominous job. Horror films depict things rising from the tomb but we must hope nothing arises from this one.

GOODBYE, WORLD

In fact, the European Union gets just over a quarter of the energy it consumes from nuclear power, although the proportion varies from one member state to another. It gets a slightly higher proportion of what is called its ‘base load power’ that way, too. Base load power is the energy source that is always available and upon which countries can fall back in times of need, the main other source being coal or, where available, gas. Other energy sources, such as wind and hydro-electric are not available everywhere, nor all the time, and are in any case dependent upon the weather. But just as coal is a constantly available source of heat (until we have used it all up, I suppose), so too is nuclear power. What’s more, nuclear power’s proponents would argue, nuclear is clean: no forests need to be chopped down, no coal mines need to be dug, there is no smoke polluting the atmosphere with particles of carbon. What ‘s not to like?

Those opposed to nuclear power would say there is a lot not to like. When things go wrong – however infrequently that may be – they go wrong in a big way. According to the National Library of Medicine at the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NIH) in the United States, “The most critical issue when considering the effects of radiation on the health of children was the increase of thyroid cancer, as clearly demonstrated among people who were children or adolescents at the time of the Chernobyl accident.”

The on-line article stresses that in the immediate aftermath of a nuclear incident, such as those at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi, the most important thing is to prevent exposure of children to radioactive iodine. Entering the body through inhalation and ingestion, it can accumulate in the thyroid. “In the longer term, another concern is exposure to radionuclides with long half-lives, including cesium137 and cesium134,” the website warns, “with physical half-lives of 30 years and 31 seconds, respectively.”

What’s more, the NIH is concerned about foetal radiation risks. Currently, radiobiological studies on low-level radiation are being reviewed, with reference to the effects upon the developing brain. As the website explains, “a foetal dose of 100 millisieverts (mSv) may increase the risk of an effect on brain development, especially neuronal migration, based upon the results of experiments with rodents.” The report recommends further research on the effects of low-level radiation, about which it feels there is too little known.

In view of all this concern about the supposed risks, should the EU be putting all its eggs into one potentially radioactive basket? It’s really a question of finding a viable alternative, and so far, nobody really has. The largest producer of nuclear power in the EU is France, responsible for 52% of the EU total nuclear energy production: 353,833 Gigawatts (GWh), followed by Germany with 9% (64,382 GWh), Spain (9%; 58,299 GWh) and Sweden (7%; 49,198 GWh). “These 4 countries together accounted for more than three quarters of the total amount of electricity generated in nuclear facilities in the EU,” says the website of the European Commission. The website goes on to explain that: “At the beginning of 2020, 13 EU Member States with nuclear electricity production had altogether 109 nuclear reactors in operation. In the course of 2020, three nuclear reactors permanently shut down – two in France and one in Sweden. Nevertheless, France remained the EU Member State most reliant on nuclear electricity, which represented 67% of all electricity generated in the country in 2020.” But France, whilst part of a minority, isn’t alone, says the Commission. “The only other EU country with more than half of its electricity generated in nuclear power plants was Slovakia (54%). This figure stood at 46% in Hungary, 41% in Bulgaria, 39% in Belgium (not any more!), 38% in Slovenia, 37% in Czechia (formerly the Czech Republic), 34% in Finland, 30% in Sweden, 22% in Spain, 21% in Romania, 11% in Germany and 3% in the Netherlands.”

At the European Parliament, a group of cross-party MEPs have formed a network to look into and try to lobby colleagues on the advantages of nuclear power. It was the idea of French MEP Christophe Grudler, of the Renew Europe group. “There is no doubt about it,” he told me, “Nuclear power is essential to achieving our European climate goals as it produces low-carbon electricity. That is why I believe that nuclear power has a strong future in the EU.” He doesn’t see nuclear as being the sole source of power. “The electricity grid must always be balanced: as renewable energies are by nature intermittent, they need a controllable and decarbonized energy such as nuclear power to supplement them quickly if there is not enough wind or sun, for example.” Grudler would like to see an educational effort to ensure that people are better informed about nuclear power because the present level of knowledge is quite poor. “For example ,” he said, “some people think that nuclear energy emits CO2, which is not true!”

As a European Commission communication on cleaning up the planet put it in 2018: “The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued in October 2018 its Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways. Based on scientific evidence, this demonstrates that human-induced global warming has already reached 1°C above preindustrial levels and is increasing at approximately 0.2°C per decade. Without stepping up international climate action, global average temperature increase could reach 2°C soon after 2060 and continue rising afterwards.” The Communication makes clear that this is not an issue we can choose to ignore because of its potential impact on us and the world at large. “The IPCC report confirms that approximately 4% of the global land area is projected to undergo a transformation of ecosystems from one type to another at 1oC of global warming, increasing to 13% at 2°C temperature change,” it continues.

“For example, 99% of coral reefs are projected to disappear globally at a temperature increase of 2oC. Irreversible loss of the Greenland ice sheet could be triggered at around 1.5°C to 2°C of global warming. This would eventually lead to up to 7 meters of sea level rise affecting directly coastal areas around the world including low-lying lands and islands in Europe. The rapid loss of Arctic sea ice during summer is already happening today, with negative impacts on biodiversity in the Nordic region and the livelihood of the local population.”

Lithuania used to boast a successful nuclear power plant at Ignalina. I visited it during one reporting trip many years ago, together with a camera crew. Construction had begun in 1974, when Lithuania was still part of the Soviet Union and the plant employed a very large number of people – more than 13,500 were employed at Unit 1 – but deployment of the second unit was postponed following the Chernobyl incident, which used the same type of Russian-built RBMK reactors, which lack a protective shield to contain any radioactivity that may leak in the event of accident. It was tough on the workers, most of whom were native Russian speakers and couldn’t therefore find alternative jobs in the country. In fact, the Chernobyl disaster was caused by a test of the safety procedures that went catastrophically wrong, leading to two separate explosions, the second of which – a steam explosion – lifted the 2,000-tonne metal plate to which the reactor was attached. A report by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) blamed it on incorrect procedures being used during the safety test, but we may never know for sure because nobody can safely go there and take a look for a very long time. At least 28 people were killed in the blast and up to 30% of Chernobyl’s 190 metric tonnes of uranium was thrown into the atmosphere.

335,000 people had to be evacuated and Soviet authorities set up a 30-kilometre-wide exclusion zone around the reactor, which some experts say will remain radioactive and extremely dangerous for literally tens of thousands of years. The disaster killed off the Ignalina power plant, upon which Lithuania depended, and made people begin to have second thoughts about nuclear power.

A NUCLEAR FUTURE

The issue of nuclear power inevitably came up at the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow in 2021. Leaders from around the world had gathered beside the River Clyde to debate climate change and how to avoid it globally. Delegates seemed to find it hard to discuss nuclear’s possible rôle in averting an energy crisis, as if even talking about it suggested an adherence to the technology. It’s certainly hard to see how global energy supplies can be maintained without it. However, even Sergey Paltsev, deputy director of the Joint Programme on the Science and Policy of Global Change and a senior research fellow at the MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Energy Initiative, admitted at COP 26 that “I wouldn’t say that it’s a rosy picture for nuclear,” although he also stressed that in the context of clean energy generation, nuclear should be taken seriously.

It’s certainly being taken seriously in Belgium: all of its nuclear plants will close by 2025, by which time Belgium has pledged to phase out nuclear power altogether. Last December, Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo confirmed that Doel 3 and Tihange 2 will close this year and next, with the newer Doel 4 and Tihange 3 shutting down by 2025. The Belgian plants are operated by the French utilities company, Engie, and account for nearly half of the country’s electricity output. Belgium has a coalition government, whose Green members called for the rapid application of a 2003 law that insists on closing the nuclear plants. Liberal members wanted to extend the plants’ lives (they failed) and it has not yet been decided how Belgium will make up the shortfall in electricity generation. According to World Nuclear News, the Belgian transmission system operator Elia has previously said that Belgium will need an additional 3.6 gigawatts (GWe) of thermal capacity by the end of 2025. The Belgian government must now wait until 15 March to see if a permit for a new gas plant, proposed to be situated just north of Brussels, will be granted. De Croo has said it’s “very unlikely” that the life of the nuclear plants could be extended if the gas plant isn’t ready in time. World Nuclear News quotes the Belgian nuclear distributor as saying: “Engie takes note of the Belgian government’s announcement concerning the nuclear power plants and recalls, as we have done on several occasions and for more than two years, that technical, legal and regulatory constraints impose an incompressible deadline that does not allow us to ensure an extension of two nuclear units for the winter of 2025.” The company also said that it would “continue to invest in renewable energies and in future innovations such as green hydrogen.”

Brussels may be the effective capital of both the EU and of Belgium, but the Belgian government’s decisions should not be confused with those of the EU. They fairly often differ, at least on points of detail. On the issue of nuclear power, they certainly do, with the EU as a whole seeing climate change as a bigger and more immediate threat than the use of nuclear fission to generate the heat needed to turn turbines, as a resolution in 2019 makes clear. The resolution was in connection with COP 25, the United Nations climate change conference before the one held in Glasgow last year. “The resolution on COP25 calls for the European Green Deal, announced by European Commission President-elect Ursula von der Leyen, to include a target of 55% emissions reductions by 2030 in order to be able to reach its target on climate neutrality by 2050. It was adopted by 430 votes in favour, 190 against and 34 abstentions.” So far, so neutral on the nuclear issue, but it continues: “The resolution says the European Parliament ‘believes that nuclear energy can play a role in meeting climate objectives because it does not emit greenhouse gases, and can also ensure a significant share of electricity production in Europe; considers nevertheless that, because of the waste it produces, this energy requires a medium and long-term strategy that takes into account technological advances (laser, fusion, etc) aimed at improving the sustainability of the entire sector’.” That looks a bit like: “yes, go ahead, but only if you really must and please be careful”, which seems fair enough. Nuclear fission can be dangerous unless you’re paying close attention.

The European Union, then, is still quite keen – at least in some quarters – on developing nuclear energy as a way of keeping the lights on while reducing the output of carbon. It won’t be cheap, however. If the Union is to hit its carbon neutrality target, it will need to spend some €500-billion by 2050. This eye-wateringly high figure comes from the EU’s Commissioner for the Internal Market, Thierry Breton, who told Le Journal du Dimanche in an interview that “To achieve carbon neutrality, it is really necessary to move up a gear in the production of carbon-free electricity in Europe, knowing that the demand for electricity itself will double in 30 years.” He anticipates an industrial revolution of “unprecedented scale” he told the newspaper. Certainly, a European Parliament resolution stresses the need for nuclear energy to be included in any long-term plans to reduce carbon emissions without reducing the amount of electricity being generated, World Nuclear News reported in January 2022.

Nuclear energy has always been a controversial topic, however. It looked as if MEPs would vote for the opposite view; “a draft of the resolution presented by the European Parliament’s Environment Committee (ENVI) had called for a phase-out of nuclear energy in the EU,” reported World Nuclear News, with MEPs claiming it is ‘neither safe, nor environmentally or economically sustainable’.” That sounds pretty definite. However, although the Environment Committee (designated ‘ENVI’ in Euro-speak) adopted the draft resolution on 6 November with 62 votes to 11, following a debate on 25 November, that decision did not make it through to the final text. Instead, amendment 38, which states that the European Parliament supports nuclear power, was approved by 322 votes, with 298 votes against and 45 abstentions. World Nuclear News reports that: “The resolution says the European Parliament ‘believes that nuclear energy can play a role in meeting climate objectives because it does not emit greenhouse gases, and can also ensure a significant share of electricity production in Europe; considers nevertheless that, because of the waste it produces, this energy requires a medium and long-term strategy that takes into account technological advances (laser, fusion, etc) aimed at improving the sustainability of the entire sector’.” The Director General of Europe’s nuclear trade group, Foratom, Yves Desbazeille pointed out that nuclear power accounts for 50% of the region’s low-carbon electricity output. The use of nuclear energy in the EU avoids the emission of 700 million tonnes of CO2 each year.

Watching this endless debate is a little like watching an extremely slow game of tennis. It should be punctuated by shouts by some umpire from the side-lines of “thirty, forty” or perhaps “deuce”. However, although it may be dull to watch, the outcome is of vital importance to us all.

NO EASY CHOICES

Europe is caught on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, energy prices are rising, putting up the cost of living for all of us. On the other hand, there is widespread agreement that we must reduce the level of our greenhouse gas emissions. It would be easier to achieve either aim – limiting energy price rises and cutting carbon emissions – if it was not important to achieve them both at the same time. They seem to be mutually exclusive. As 2022 began, on New Year’s Eve, the European Commission presented the EU’s 27 member states with a new draft regulation in which both natural gas and nuclear power were designated as “green fuels” for generating electricity. There are plenty of people, especially in the Green camp, who see nuclear as something to be avoided because of the fear of a radiation leak. However, as the draft regulation says, nuclear produces virtually no emissions, while gas offers a relatively clean transition fuel as the EU looks for ways to phase out coal completely. If the European Parliament and the member states agree to play ball on this point, then nuclear power and gas will be listed alongside wind and solar as suitable technologies for private investment and for EU financial support from 2023 on. What’s more, says the Foreign Policy website, “an official EU designation as green may help private companies, including lenders, meet increasingly ubiquitous environmental, social and governance mandates”. The inclusion of gas is not uncontroversial: some climate-minded European governments still count gas (understandably) as a fossil fuel, but it’s over the inclusion of nuclear energy that things get difficult. It’s a fact, however, that nuclear reactors can generate electricity 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year, while wind and solar stop working when the wind dies down or the sun sets. The Commission’s move may not be popular in some quarters, but it seems unavoidable.

MEPs and member state governments had been warned back in 2018 that in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, power generation overall must rise by up to two-and-a-half-fold. It also warned that nuclear would have to be part of the mix.

You may not be surprised to hear that France is the keenest member state where nuclear power is concerned. There is plenty of opposition, however. The Social Democrats who, together with the Greens, have taken over from Angela Merkel’s government in Germany are firmly anti-nuclear and intend to phase out all nuclear power by the end of 2022. Neighbouring Austria is even more strongly opposed, although France gets the support of Finland and the Czech Republic. Those who are so keen to get rid of nuclear power still haven’t really explained how they plan to keep the lights on without it. It seems doubtful that wind turbines or solar farms will be able to bridge the cap, and certainly not all the time. France, dependent on nuclear power for almost 70% of its electricity, has the lowest carbon emissions per capita of all EU countries. Germany, which saw an increase in both the use of coal and its emissions, is way above the EU average, around six time more per capita than France, despite defining itself as “a green forerunner”.

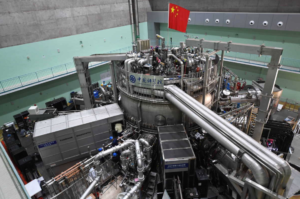

“No solution should be put aside by dogmatism,” warned Christophe Grudler. “It seems unthinkable not to use the decarbonised energies we have.” He pointed out that this could even be seen as a way for Europe to become more independent in its energy supply and less reliant on foreign sources. “The end of fossil fuels – 60% of which come from other continents – must be an opportunity to replace them with energy ‘made in Europe’, in the name of our strategic autonomy,” Grudler pointed out, while acknowledging that Europe must continue to invest in research on nuclear energy, “for example nuclear fusion”. There is a lot of research currently under way to develop nuclear fusion but it’s some way from becoming a viable energy source. Early in January, however, China’s “Artificial Sun” nuclear fusion reactor in Hefei set a new world record by running at almost 70-milliono Celsius for more than 17 minutes. Nuclear fusion works by forcing hydrogen atoms to join together to form helium, just as they do in the heart of the sun (and all other stars). The stars, with their huge gravity, find it easy; on Earth it’s much less so, because the nuclei of the hydrogen isotopes involved strongly repel each other. The trick is to get ignition so that the reaction is self-sustaining, then to keep feeding it fuel. In theory, it should be much more efficient than nuclear fission. “The D-T fusion reaction releases over four times as much energy as uranium fission,” according to the World Nuclear Association (WNA). It requires containment by means of a magnetic shield. It’s not easy, though, nor cheap.

“The transition towards climate neutrality by 2050 gives energy a central role,” says the European Commission, “as energy is today responsible for more than 75% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions.” If anyone thinks that should be doable with a little research, bear this in mind: “To reach climate neutrality, we need to decarbonise at least six times faster than anything realised globally so far. We must drastically increase the share of renewable energy sources and clean energy carriers and improve energy efficiency.” It all costs money, but Grudler thinks it would be well worth it. “We need the right signals from decision-makers so that energy companies can invest in technology and innovation without fear of backlash.”

In the UK, a new and surprising lobbying organisation has been set up to put the case for nuclear power, called Greens for Nuclear Energy. “We believe that the increasingly urgent need to deal decisively with our emerging climate crisis makes continued opposition to nuclear energy irrational for environmentalists and reduces our chances of averting a climate catastrophe” says the group’s website. On the same website, Professor Gerry Thomas, Chair in Molecular

Pathology at the Faculty of Medicine, Department of Surgery & Cancer at Imperial College London even plays down concerns about the long-term effects of the Chernobyl disaster. “I can understand that people may be nervous about nuclear power,” he is quoted as saying. “I was too, until I started working on the health effects of the Chernobyl accident. Now, 35 years later, we can say that the only health effect caused directly by exposure of the population leaving near the site of the Chernobyl accident has been an increase in thyroid cancer in those who were children at the time of the accident.”

Apparently, thyroid cancer is relatively responsive to treatment. Another scientist quoted on the site is François-Marie Bréon of the Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement (LSCE), who wrote: “Nuclear will not be sufficient to stop climate change. Yet, it can definitely provide a large contribution.

Coal fired power plants generate roughly one third of global CO2 emissions. These may be replaced by nuclear plants in many countries such as Europe, the USA, China, India and others. The world needs to engage into nuclear power at the same rate as France did during the 70s and 80s.”

Some people are never going to accept a solution that contains the word ‘nuclear’. The very term sends shivers up the spines of some people, and in the light of Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi, it’s an understandable reaction. The fact remains, however regrettable, though, that the alternative would appear to be runaway climate change, melting glaciers and ice sheets, desertification and so on, leading to the extermination of much of the life on planet Earth. The problem is also highlighted on the United Nations’ website: “Effects include increases in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events – including flooding, droughts, wildfires and hurricanes – that affect millions of people and cause trillions in economic losses.” “Human-caused greenhouse gas emissions endanger human and environmental health,” says Mark Radka, Chief of the UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP) Energy and Climate Branch. “And the impacts will become more widespread and severe without strong climate action.” The EU’s own website states clearly: “Climate related extremes such as forest fires, flash floods, typhoons and hurricanes are also causing massive devastation and loss of lives, as hurricanes Irma and Maria proved in 2017 when they hit the Caribbean, including a number of European outermost regions. This is now affecting the European continent with storm Ophelia in 2017 being the first strong East Atlantic hurricane ever to reach Ireland and in 2018 storm Leslie bringing destruction to Portugal and Spain.” The EU is committed to ending global warming, it seems, even if that means using nuclear power, and it is putting money into something it seems we’re all going to have to get used to, like it or not.