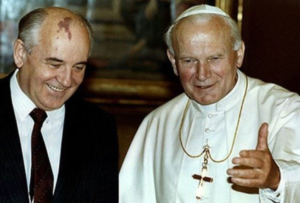

Memorial service conducted for Mikhail Gorbachev, the last General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and last President of the USSR, at the Pillar Hall of the House of Unions, Moscow © Wikicommons/Sergio Oren

It was the great French novelist and fervent believer in literary realism, Gustav Flaubert, who wrote in a letter to his lover, Louise Colet in June 1853: “On peut calculer la valeur d’un homme d’après le nombre de ses ennemis et l’importance d’une oevre du mal qu’on est dit” (You can calculate the worth of a man by the number of his enemies, and the importance of a work of art by the harm that is spoken of it). I’m not sure what he’d have made of Mikhail Gorbachev, a man who brought peace and tranquillity to a world on the edge of a nuclear abyss. Those of us saved from a tragic war still admire him as the Soviet Union’s most peace-loving (as well as being the last) leader before its dissolution. Gorbachev had achieved single-handedly something that the united forces of NATO had been unable to achieve: the fall of the Iron Curtain. That’s the whole point, really: he succeeded in bringing an end to the nuclear threat that had hung over us all for years, by ending Russia’s terrifying counter-balance to the West and the threats they represented. Putin, on the other hand, is a man who likes to make threats. He denied Gorbachev a State Funeral and declined to attend the more normal funeral that saw Gorbachev interred next to his late wife, Raisa, although thousands of ordinary Russians were there. Apart from showing a lack of respect for the march of history, it also displays an alarming level of simple bad manners and rudeness.

“In the mid-80s,” Gorbachev told me back in 2008, during an unscheduled and off-the-cuff interview, “the leaders of the big states realised that there is an urgent need to do something.” He was not above bringing himself into his proclaimed description of our reality, “Then God made the ways of Gorbachev, Reagan, Bush, Thatcher, Mitterrand, and others – and they were wise enough to overcome clichés and prejudices regarding each other and start talking about the nuclear threat.

Now the world and our times are different, there is globalisation, countries are more interdependent and countries like Brazil, China and India have come onto the stage.” As we now know, of course, and he clearly could not have known back then, was that ambitious demagogic leaders can still overturn the applecart through ruthless ambition. I think he’d have been very disappointed to find that the culprit would be the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin. His words, though, had been remarkable, and spoke of peace.

I remember at my primary school, when I was 9 or 10 years old, the regular testing of the air raid siren mounted on the school roof. When that happened, the noise was too loud for lessons, so we kids quite enjoyed it. Since the school – and, indeed, the entire town – lacked any kind of nuclear bunker, I’m not sure what we were supposed to do if it sounded for real, which, of course, it never did. When I met Gorbachev, I was struck by how much shorter he was than I had anticipated. A great man, the leader of a great world power, should be gigantic and physically powerful, more like, say, the Hulk. Gorbachev, very clearly, was not like that.

It was a fortuitous but accidental encounter, inside the European Parliament in Brussels, when I spotted him standing in the corridor, together with his interpreter, just outside the press bar and between it and the press conference room named, somewhat ironically, for Anna Politkovskaya, the Russian journalist whose courageous reporting of the Chechen war and trenchant criticism of Putin was presumably responsible for her being shot dead at point blank range inside her Moscow apartment. From 1999 until her death on 7 October 2006, she served as a war correspondent (she was always described as a reporter, not a war correspondent, because she concentrated on the suffering of civilians) for the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, set up, ironically, by Gorbachev, using money from his 1990 Nobel peace prize. Politkovskaya often travelled to the front lines to document the frequent abuses by Russian troops and their Chechen allies against those fighting for independence and the long-suffering ordinary civilians. The Russians organised camps where Chechen prisoners often faced torture, rape, severe beatings, and mutilations. The dead were mainly dumped in mass graves by the Soviet troops. In today’s Russia, Putin would probably have called the war “a special military operation” or some other such silly and inaccurate euphemism. Politkovskaya also reported on Putin, who was Yeltsin’s prime minister at the time. In fairness, I must point out that it was Chechen militants who started the war by invading Dagestan. Politkovskaya never avoided telling the truth and repeatedly pointed out that fact.

But getting back to my meeting with Gorbachev, I was struck not only by his relatively modest size but by his modest demeanour, too. He agreed to be interviewed for radio (I’m afraid I do not recall the radio station concerned, whose name seemed not to interest him anyway) and we settled down to a stand-up interview. He was fulsome in his answers and extremely cooperative and friendly. His interpreter was only required so that I would understand his replies. He spoke nothing but Russian during the interview, but he always started answering me before his interpreter had finished translating my questions, which showed he had a pretty good grasp of English, even if he chose not to speak it. I suspect that was because he wanted to be sure there could be no ambivalence about his views and not because it is the language of the United States, the Soviet Union’s former long-term rival for world supremacy. Putin’s decision not to attend Gorbachev’s funeral, let alone grant him a state funeral, is clear proof of the current Russian President’s lack of manners and appropriate respect for a great man, even if he disagreed with his views. It would not have surprised Gorbachev at any rate. Putin was, after all, the choice for leader of Boris Yeltsin, who was not always a good judge of character, even when sober. I met him, too, but he was much too busy to speak to a random and (to him) unknown journalist, although he did make a grunt that defied interpretation.

He did, however, come to Gorbachev’s rescue when coup plotters tried to remove him from office in 1991 for being too soft with the West. It seems that the hawks in the Kremlin always wanted a war, never heeding the words of the song first recorded for Tamla Motown by the Temptations and written by Norman Whitfield, a member of the group, but then made a massive hit by Edwin Starr:

“War, huh, yeah

What is it good for

Absolutely nothing

Uh-huh”

It topped the US charts for three weeks and even earned Starr a letter of congratulations from Beatle John Lennon. I don’t imagine that members of the Politburo are terribly keen on pop music, even if the public love it. There was never a song called “Special Military Operation, huh Yeah; What is it good for.” I wonder why, since they mean the same thing.

LESSONS FROM WHICH PAST?

In Moscow and other Russian cities today, Gorbachev’s legacy is a mixed one. Many ordinary Russians blame him for “losing” the Cold war and for the subsequent break-up of the Soviet Union, which Putin has described as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century”, although that is not a view shared in, say, Ukraine, Moldova or Lithuania, and many other former satellite states. Even so, hundreds of ordinary Russian citizens lined up outside the Hall of Columns to pay their respects to Gorbachev in the same place that, for instance, Joseph Stalin and Vladimir Lenin are commemorated. Today’s world is – marginally – less embroiled in war. “The most important lesson we can take is that a dialogue has to be developed,” Gorbachev told me. “Confidence has to be built. We have to renounce the politics of force, they bring nothing good. We have to understand that we are all in the same boat, we all have to paddle.

If not, some are paddling, some are pouring water in, others might even be making a hole in it. Nobody will win in this manner in this world.” He’s indisputably right, but is that Putin and one or two others I can see over there with big jugs of water and electric drills in their hands?

I suppose there are enough people in Russia and its former satellites who hate him to qualify him under Flaubert’s reckoning as a “man of worth”. His greatest legacy is, undoubtedly, the relative peace that the world enjoys, despite the conflicts that continue in various places. There are no longer two nuclear-armed superpowers threatening to obliterate us all. I can still remember the television warnings that were broadcast while I was still at primary school (on a tiny, black-and-white, 30 cm-screen) urging us to seek shelter underneath something solid if we hear the air raid sirens. Exactly how safe we ‘d have been underneath my mother’s dining table if a nuclear weapon detonated nearby was never fully explained. Fortunately, Armageddon never arrived, and we have Gorbachev to thank for ensuring it never would, or not soon, anyway.

He visited the European Parliament several times and his message was always one of peace and the need to preserve it, although he also spoke on environmental matters, including the importance of ensuring a supply of clean drinking water everywhere. It was peace, however, that dominated his interview with me. He told me he believed that the key to peace was – and will always be – dialogue. The dismissive attitude of Putin and the old guard at the Kremlin towards Gorbachev’s death probably provides enough enemies to justify him as a man of worth under Flaubert’s criteria. Since his death in August 2022, following a long illness, top political figures from around the world have been quick to praise his unique legacy. When I spoke to him, he talked about how other world leaders should overcome their remaining prejudices and talk peace, or at least talk to each other, so that the nuclear threat – indeed, the threat of warfare in any form – could be diminished. Given the current circumstances, there seems little chance of that happening.

He talked a lot about such things as trust, co-operation, dialogue, mutual help, and mutual exchange. He said he believed that the success of Europe is largely down to the existence of the European Union, which he admired. “We have to renounce the use of force,” he told the European Parliament in his speech to MEPs. As recent history has shown, it’s not a view shared with his successor, Putin, who was, at that time, a relatively lowly (but very ambitious) KGB operative, working mainly in St. Petersburg during Gorbachev’s rule. Putin had worked as a chinovnik (the word is a carry-over from earlier times, meaning a minor official or office-holder under tsarist rule) in Dresden, East Germany, for 5 years. He’d worked as a liaison officer between the KGB and East Germany’s feared secret police, the Stasi. He had told his mentor, the film-maker Igor Shadkhan, that he had quit the KGB because a changing Russia had left him with no rôle to play. He even talked of becoming a taxi driver. If only! Like many of Putin’s claims, at that time and since, it was a lie. Even so, Putin had witnessed the dissolution of the Soviet Union (and the Soviet dream of world domination) from the security of the KGB’s villa overlooking Dresden itself. The dissolution meant the arrival of nationalist movements in countries Moscow had considered its own, with which Gorbachev had been obliged to compromise. Soon after the failed hard right coup attempt, Yeltsin emerged as the man to watch. He promptly banned the Communist Party – something that is often forgotten, despite having been such a momentous decision – and suddenly the world was changed completely.

According to Catherine Belton in her highly informative book “Putin’s People”, Putin was still there and has given several different accounts of his departure from the KGB, none of which is true. Russia continued to recruit pro-Russian agents in the new independent East Germany. Ms. Belton claims that the STASI’s political prisoners (and there were many) were held in tiny windowless cells and treated extremely badly, none of which is likely to come as a surprise to you.

HOW DID WE GET FROM THERE TO HERE?

Gorbachev told me that meaningful conversation is the most important thing to achieve. World leaders may meet, may even talk to each other, but they talk with closed ears. The communication must be two-way, although that can be difficult to achieve. “Look at the US in Iraq,” he reminded me, “Everybody was opposed, even their allies, but they did not listen and what happened? They do not know how to get out of it now.” They didn’t: even though the US and its allies (chiefly the United Kingdom) succeeded in overthrowing Saddam Hussein quite quickly, they then went on to occupy the country, sparking a violent insurgency, aiming to overthrow the Americans. Not all had been peaceful within Iraq for reasons of religious difference. Saddam had banned Iraqis from making pilgrimages to the Shi’ite holy cities of Najaf and Karbala, leading some ayatollahs (local religious leaders) in southern Iraq keen to get away from areas controlled by Saddam’s forces and to seek more peaceful lives out in the countryside. As they started to return and the pilgrimages resumed, Iraqis also began the hunt for their bodies of their loved ones. After the many pogroms of the Saddam regime, there were thousands of them to find.

Sectarian violence swept the entire country, with many killings between the Shi’ite and Sunni armed groups. One, formed by a tough-talking cleric, Muqtadā al-Ṣadr, was called the Mahdi Army and was famously effective against both US and Iraqi forces on behalf of the Shi’ites, further destabilising an already very unstable country. The occupation and the continuing war divided American opinion, with the war becoming deeply unpopular with the emergence of American soldiers appearing to abuse and brutalize Shi’ites being held at Abu Ghraib prison, which became synonymous with cruelty and, basically, inhuman imperialism. By October 2009, the Pentagon had estimated that more than 4,300 American soldiers had been killed in the war. The controversy raged on and in 2011, new President Barrack Obama ordered his troops home, ending this controversial and largely unpopular war. Something had to change to prevent further deadly and relatively pointless wars. “After the Cold War,” Gorbachev told me, “Everybody was talking of the ‘New World Order’. Even the Pope joined us and said a ‘New World Order’ is necessary: more stable, more fair, more human.” A nice idea, but human beings have a poor record for adhering to such ideas and principles when they can advance their cause more quickly with a bullet in the brain of an opponent or a stiletto between their ribs.

Gorbachev said he had hoped that world powers had ‘learned their lessons’, but of course they hadn’t. World leaders, it seems, cannot resist trying to seize the initiative in order to benefit from any global event and turn it to their advantage. The Pope and others may have been ready to welcome in the fabled ‘New World Order’. “However, when the USSR fell apart – because of internal reasons first of all – the US could not resist the temptation to use the confusion,” he told me, although it was a well-known fact at the time. “Political elites changed, those who brought the world out of the Cold War left the stage, the new ones wanted to write their history.”

The only surprising thing about Gorbachev’s opinion is that what happened seems to have come as a surprise to him. He had been around for long enough, had seen enough to know what human nature is like, up at the sharp end. Perhaps “surprised” is not the right word? Perhaps he was just “disappointed”. That, I could well understand. It disappointed him, but it also seems to have worried him. “Those errors of vision, poor decisions and missteps made the world ungovernable,” he told me. “We live in a world of chaos. New ways of life and new political mechanisms can emerge from the chaos, but the chaos can also lead to disruption, resistance, and armed conflict.” Yes indeed, it certainly can.

BREATHE DEEPLY (WHILE YOU STILL CAN)

Apart from world geopolitical events, Gorbachev was also deeply concerned by what has been going wrong with the environment, especially the availability of clean, drinkable water and the safe disposal of health-threatening waste. There are several charitable organisations devoted to this issue, including ‘Water.Org’, who set out their intentions on their website: “We believe water is the best investment the world can make to improve health, empower women, enable access to education, increase family income and change lives. Yet, 771 million people lack access to safe water.” That’s a damning indictment and it seems the organisation had the support of Gorbachev, although his environmental interests were wider than that. Access to clean drinking water and the safe disposal of waste matter would be a huge step in the right direction, he told the European Parliament. “The major problems are poverty, air and water quality, unsanitary conditions, low agricultural productivity, but all of them are about ecology,” he said in reply to my question about environmental degradation. “It is nonsense to say that ecology is a luxury – it is a major priority of our times.” After all, it’s been reported that this year’s drought in Europe has been the worst in 500 years. In Germany’s Elbe River, a carving made in 1616 is meant to be underwater and therefore hidden from sight.

Known as “the Hunger Stone”, it provides a warning that the worst droughts will lead to very poor harvests and starvation as well as being a visible indicator of just how serious a drought is becoming; in severe droughts it appears above the surface of the water, rather than being hidden beneath the surface, as usual. Carved on it are the words: “Wenn du mich siehst, dann weine”, which means “If you see me, weep.” Now, farmers who have harvested olive trees on their land for generations are seriously worried because of the toll being taken by the lack of adequate rain. Spain’s olive farmers are anticipating a reduction in the harvestable crop of up to 38%. Other edible oils are likely to remain available at inflated prices and with diminished quality, but it may take a while for the olive crop to get back to normal, if it ever does. Normally, olive trees are long-lived plants, with the oldest known one being the olive tree of Vouves, believed to be at least 2000 years old. That’s unusual, but it’s fairly common for olive trees to last for 500 years or more, during which time the occasional drought can hardly have been unknown. Obviously, keeping them in sunny spots and also well-watered and well drained is essential.

There’s no doubt that Gorbachev had a point when he expressed concern about mankind’s cavalier attitude towards maintaining a safe, clean and well-watered environment. But it’s not the only issue that worried him. “The second priority is the fight against poverty because two billion people are living on $1 to $2 a day,” he said. “The third one is global security, including the nuclear threat and weapons of mass destruction.” That’s a fairly formidable list of things that are wrong with the world and not visibly getting better. “These are three urgent priorities,” Gorbachev said, “but I put ecology in the first place, because it directly touches all of us.” Anyone who has been affected by this year’s drought would doubtless agree that it touches us all. Unlike the olive tree we can’t maintain healthy humans simply by putting them in a sunny spot that’s also well-watered and well drained. There’s rather more to it than that. Finding somewhere peaceful would be helpful, too, although in Ukraine, for example, that’s not easy right now.

The problem, as Gorbachev admitted to me, is that his Gorbachev Foundation’s motto, “Towards a New Civilization”, cannot be easily realized without resources. Everything good costs money. “It’s not always about money,” Gorbachev replied when I mentioned that good things don’t come cheap. “If international issues are handled in a disorderly way, you need more money. It is about trust, co-operation, dialogue, mutual help, and mutual exchange.” Interestingly, Gorbachev then gave his advice about the EU which, sadly, the British voters failed to hear. Or at least, failed to observe. “Why is Europe growing economically?” he asked, before going on to give his own answer, that it’s: “because of the existence of the EU. This is the path of new opportunities, and the EU is a good example.” It almost sounded as if Gorbachev was suggesting that Russia should apply to join the EU itself. It never will, of course, and probably would be turned away as too large a country to come on board; a shark among so many relative minnows. Indeed, Putin has branded the EU “stupid” for trying to impose price caps and other restrictions on the flow of Russia’s gas. It all seems rather strange: I can remember being stopped in the street one day, not far from the European Parliament’s Brussels building, by a former German Socialist MEP who was trying to persuade me to invest in Russia’s Nordstream gas pipeline.

She’d taken on a consultancy position with the company. I didn’t take her up on the suggestion. Putin, of course, is now threatening to withhold any form of energy from Europe as punishment for Europe’s refusal to countenance Russia’s takeover of Ukraine, whether it’s a war, an invasion or a “special military operation”, which is an invasion dressed up in fancy words. Whether or not the entire EU, with its variety of sometimes opposing opinions, can unite on a common energy policy or not is as yet uncertain. Experts suggest that Putin’s aim is not to freeze EU citizens this winter, nor to ramp up energy prices: he wants to cause tensions that will break up the EU.

He doesn’t like successful organisations that oppose Russia’s actions, however meekly, it seems. It’s been suggested that it’s even part of a plan to take NATO apart by causing friction within it.

FUELLING POTENTIAL CONFLICT

The fact is that Europe is dependent on fossil fuels from Russia: 38% of the gas EU countries consume comes from Russia, that’s up from 27% just nine years ago. Russia recorded its highest ever current account surplus this summer, partly because Putin keeps putting the price up but also because Russian imports are so low. That, however, may not be sustainable for Russia, because if it is to expand as an economic power, or even maintain its manufacturing levels, it will need to get hold of the goods it is no longer buying. Nobody is gaining from Putin’s stupid and pointless war, not even Putin and his lapdog Kremlin. However, it’s hard to see how any country could hope to replace the vast quantity of fossil gas Russia supplies to Europe, and emissions from gas consumption now exceed those from burning coal. According to the European Commission, the EU must eliminate the use of fossil gas by 2050 if the rise in global warming is to be restricted to just 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Currently, the burning of fossil gas is responsible for more carbon emissions than coal. The Paris agreement set the target of restricting the global temperature rise to below 2° Celsius, with 1.5° as the ideal goal. Writing on the Science Analytics website, Dr. Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, Head of Climate Science and Impacts, said that: “Science from the IPCC (the International Panel on Climate Change) is clear: limiting warming to 1.5°C can avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Many changes become larger in direct relation to more warming, and every fraction of a degree makes a difference. Every avoided increment of warming would reduce extremes such as heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and droughts, as well as long-term impacts and the risk of crossing tipping points of the Earth System.” Having witnessed this year’s unusually high temperatures and the ensuing drought, we must conclude that he has a point.

How, then, even with Gorbachev’s ideas, can we reduce Europe’s dependence on Russia’s fossil gas? Tara Connelly, senior gas campaigner with the international NGO Global Witness, suggests that Putin could simply turn off the gas taps. “More gas isn’t a long-term solution,” she told CNN, “The flag on the pipeline or ship is irrelevant – it’s Europe’s dependency on the fuel, regardless of where it’s from, that makes it so vulnerable to the vagaries of the global gas market.” And, of course, to the aggressive territorial ambitions of the Russian president. The European Commission wants to see the gas market reformed, but the energy companies, revelling in the record profits they’ve been enjoying, are opposed. Naturally. Connelly points out that the CEO of BP, for instance, Bernard Looney, has called for more investment in gas, while nothing is being done to find ways of reducing demand. As prices continue to rise, more and more EU citizens are going to struggle to pay soaring bills, while facing the increasing risk of a cold winter. How can governments and the EU address such a massive problem while it’s being deliberately made worse by a war-mongering megalomaniac like Putin?

“It is not always about money,” Gorbachev told me, when I asked him what his “New Civilisation,” would look like. Reading his answer, you must bear in mind that the interview was conducted several years ago, when the EU’s future looked brighter, more united and in which Russia had not yet invaded Ukraine. “If international issues are handled in a disorderly way, you need more money. It is about trust, co-operation, dialogue, mutual help, and mutual exchange.” Yet again, Gorbachev was calling for dialogue and co-operation. “Why is Europe growing economically? Because of the existence of the EU,” he told me. “This is the path of new opportunities, and the EU is a good example.” It is too good an example, it seems, for Putin to leave it alone. It is also a group of nations working together (most of the time, at least) that is not headed by Putin himself, which is a situation he seems to find offensive. Even then, Gorbachev could see where the seeds of discord either had been or would be sown. “Of course, not everything is perfect,” he conceded, “In my view the EU is already over-charged as a system. It has to have wisdom and know when to stop, absorb, move forward, not just hurry and make hasty headlong jumps.”

I cannot remember the EU making many “headlong jumps”, hasty or not, although I remember attending and reporting on a few enlargement ceremonies. It may get larger again, too. Current candidates include Albania, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey, while Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo are seen as potential members at some future date. Turkey’s membership is a long way off and, like all of those wanting to join, it would offend the Kremlin by doing so. Gorbachev, though, would have approved. Sadly, men of peace seldom get to run countries whose politicians are hungry for conquest and whose arms industries sniff a profit in warfare. In 1987, in a speech to the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party, Gorbachev said: “At some point, the country began to lose momentum, difficulties and unresolved problems started to pile up, and there appeared elements of stagnation and other phenomena alien to socialism. All this badly affected the economy and social, cultural and intellectual life.” Thanks to him, it did not lead to conflict because, unlike Putin, he preferred peace and mutual tolerance to war. He will be greatly missed.